Part 1: from Practice to Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust Delivering Focused and Targeted Travel Information to Staff

1 The Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust Delivering focused and targeted travel information to staff This case study identifies some of the key About Pennine Acute considerations when providing information The Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust has about travel choices at a workplace. It hospital sites in Oldham, Rochdale, North draws on the support provided by Transport Manchester and Bury. A dedicated Travel and for Greater Manchester’s Travel Choices Access Manager is in place. The role involves programme to Pennine Acute NHS Trust to the implementation of a range of measures improve the information about travel options across the organisation to support access to the made available to staff. It includes learning Trust’s sites by staff, patients and visitors. and top tips relevant to any workplace. Travel information at Pennine Acute Pennine Acute already had a comprehensive range of travel information available for staff, patients and visitors, including parking arrangements, public transport options and information on facilities for cyclists at the workplace. Information included: North Manchester General Hospital Delaunays Road, Crumpsall, Manchester, M8 5RB Details Notes and Links Site Map Site Map – Link to Pennine Acute website Bus Stops, Services Bus Stops are located within and on the road alongside the hospital site and are Travel options for staff leaflet and operators letter coded. The main bus service is the 42 East Didsbury, Oxford Road, City Centre, Cheetham Hill, NMGH, Blackley, Middleton; using Stop C at the Made available to new starters as part of hospital. For more details visit www.crossconnectbus.com . Further information on bus stops and buses serving the site is on the Trust induction and on the staff intranet. -

Buses Serving North Manchester General Hospital

Buses serving North Manchester General Hospital 52 Salford Shopping City, Broughton, Cheetham Hill, NMGH, Harpurhey, Moston, Newton Heath, Failsworth Tesco Bus Stops Daily service, operated by First Greater Manchester A,C, Pendleton Higher Broughton Cheetham Hill NMG Moston Newton Heath Brookdale Failsworth D,E,F Salford Shopping City McDonalds Crescent Road Hospital Ben Brierley Dean Lane Park Tesco Store 27 16 7 12 21 26 32 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 53 Cheetham Hill, NMGH, Harpurhey, Miles Platting, SportCity, Gorton, Belle Vue, Longsight, Rusholme, Central Manchester Bus Stops Hospitals, Hulme, Old Trafford A,C, Daily service, operated by First Greater Manchester D,E,F Cheetham Hill NMG Harpurhey Sport Gorton Belle Rusholme University Old Trafford Salford Crescent Road Hospital Rochdale Rd City Vue of Manchester Trafford Bar Shopping City 7 7 16 31 35 50 58 68 80 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 88=> Circulars, Manchester City Centre, Monsall, Moston, White Moss, Blackley, NMGH, Cheetham Hill, Manchester City Centre 89<= Daily service, operated by First Greater Manchester (Evenings, Sundays and Bank Holidays—JPT) Use these buses and change at Crumpsall Metrolink Station or Cheetham Hill, Cheetham Hill Rd (Bus 135) for Bury. Bus Stops Manchester Central Moston White Blackley Bank Crumpsall NMG Cheetham Manchester -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Council, 11/09/2019 18:00

Oldham Borough Council Council Meeting Wednesday 11 September 2019 OLDHAM BOROUGH COUNCIL To: ALL MEMBERS OF OLDHAM BOROUGH COUNCIL, CIVIC CENTRE, OLDHAM Tuesday, 3 September 2019 You are hereby summoned to attend a meeting of the Council which will be held on Wednesday 11 September 2019 at 6.00 pm in the Council Chamber, Civic Centre, for the following purposes: 1 To receive apologies for absence 2 To order that the Minutes of the meeting of the Council held on 10th July 2019 be signed as a correct record (Pages 1 - 32) 3 To receive declarations of interest in any matter to be determined at the meeting 4 To deal with matters which the Mayor considers to be urgent business 5 To receive communications relating to the business of the Council 6 To receive and note petitions received relating to the business of the Council (time limit 20 minutes) There are no petitions to note. 7 Youth Council (time limit 20 minutes) There is no Youth Council business to consider. 8 Questio n Time a Public Questions (time limit 15 minutes) b Questions to Leader and Cabinet (time limit 30 minutes) c Questions on Cabinet Minutes (Pages 33 - 50) (time limit 15 minutes) 24th June 2019 22nd July 2019 d Questions on Joint Arrangements/Partnerships (Pages 51 - 130) (time limit 15 minutes) Greater Manchester Health and Care Board 31st May 2019 Greater Manchester Transport Committee 12th July 2019 Greater Manchester Waste and Recycling Committee 14th March 2019 National Park Authority 5th July 2019 (AGM) 19th July 2019 Mio Care Board 11th March 2019 Greater Manchester Combined Authority 28th June 2019 9 Notice of Administration Business (time limit 30 minutes) Motion 1 Councillor Shah to MOVE and Councillor Chauhan to SECOND: Kashmir This Council notes with concern (i) the Indian Government’s decision to remove Article 370 and 35A from the Indian Constitution, which grants special status to Indian-controlled Kashmir, the recent movement of troops into Kashmir and the imposition of travel restrictions and a communications blackout affecting landlines, mobile phones and the internet. -

INSTITUTE of TRANSPORT and LOGISTICS STUDIES WORKING

WORKING PAPER ITLS-WP-19-05 Collaboration as a service (CaaS) to fully integrate public transportation – lessons from long distance travel to reimagine Mobility as a Service By Rico Merkert, James Bushell and Matthew Beck Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies (ITLS), The University of Sydney Business School, Australia March 2019 ISSN 1832-570X INSTITUTE of TRANSPORT and LOGISTICS STUDIES The Australian Key Centre in Transport and Logistics Management The University of Sydney Established under the Australian Research Council’s Key Centre Program. NUMBER: Working Paper ITLS-WP-19-05 TITLE: Collaboration as a service (CaaS) to fully integrate public transportation – lessons from long distance travel to reimagine Mobility as a Service Integrated mobility aims to improve multimodal integration to ABSTRACT: make public transport an attractive alternative to private transport. This paper critically reviews extant literature and current public transport governance frameworks of both macro and micro transport operators. Our aim is to extent the concept of Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS), a proposed coordination mechanism for public transport that in our view is yet to prove its commercial viability and general acceptance. Drawing from the airline experience, we propose that smart ticketing systems, providing Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) can be extended with governance and operational processes that enhance their ability to facilitate Collaboration-as-a-Service (CaaS) to offer a reimagined MaaS 2.0 = CaaS + SaaS. Rather than using the traditional MaaS broker, CaaS incorporates operators more fully and utilises their commercial self-interest to deliver commercially viable and attractive integrated public transport solutions to consumers. This would also facilitate more collaboration of private sector operators into public transport with potentially new opportunities for taxi/rideshare/bikeshare operators and cross geographical transport providers (i.e. -

Winton, Greater Manchester

Winton, Greater Manchester Coordinates: 53°29′10″N 2°21′54″W / 53.486°N Road, and St. Mary Magdalene’s Parish Church on Gras- 2.365°W mere Crescent/Westbourne Road ( Grade II listed build- ing). There is a Baptist church (although its old building Winton, originally “Withington”[1] is an area north-west of Eccles in Salford, Greater Manchester, England. The in Parrin Lane is now closed). The oldest building is Mag- dalene Centre, formerly a school before Westwood Park population of the City of Salford ward at the 2011 census was 12,067.[2] was opened, dating from 1888. Historically in Lancashire, Winton is a residential area surrounded by Patricroft, Peel Green, Monton, Barton- 2.4 Transport upon-Irwell, Eccles and Worsley. 2.4.1 Buses 1 Geography and administration First Greater Manchester and Arriva North West oper- ate bus services through Winton from Eccles town cen- Winton is between Monton, Worsley, Peel Green and tre, Manchester, the Trafford Centre and Wigan. Win- Patricroft, divided by the motorway interchange of the ton is also a through-route for buses to the Trafford M602, M60 and M62. The boundaries of Winton are Centre, Wigan, Worsley and Eccles. The following Ar- the Liverpool-Manchester railway on New Lane (borders riva Routes service Winton: 61, 62 (Eccles Circulars) with Peel Green), the railway on Worsley Road (borders and the 66 Clifton-Salford Royal Hospital. The follow- with Patricroft), the Bridgewater Canal bridge at the top ing First Manchester Routes Serve Winton: 68 Trafford of Parrin Lane (borders with Monton) and the Worsley Centre-Bolton (Little Hulton/Farnworth after 18:00), 33 Road/Barton Road change (borders with Worsley). -

Council & PTE Section

ENGLISH COUNTIES See also the Links section for additional web sites for many areas UPDATED 28/04/18 Please email any comments regarding this page to: [email protected] ‘TRAVELINE’ www.traveline.info/about-traveline/traveline-services Traveline offers nationwide bus information on 0871 200 2233 Calls cost 12p per minute plus the phone company’s access charge Black enquiry line numbers indicate a full timetable service; red numbers imply the facility is only for general information, including requesting timetables. Please note that all details shown regarding timetables, maps or other publicity, refer only to PRINTED material and not to any other publications that a county or council might be showing on its web site. ENGLAND BEDFORDSHIRE BEDFORD Borough Council No publications Public Transport Team, Transport Operations See also Central Bedfordshire Borough Hall, Cauldwell Street, Bedford MK42 9AP Tel: 01234 228337 Fax: 01234 228720 Email: [email protected] www.bedford.gov.uk/transport_and_streets/public_transport.aspx COUNTY ENQUIRY LINE: 01234 228337 (0800-1730 M-Th; 0800-1700 FO) PRINCIPAL OPERATORS & ENQUIRY LINES: Grant Palmer (01525 719719); Stagecoach East (01234 220030); Uno (01707 255764) CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE Council No publications except for a Public Transport, Priory House, Monks Walk System Map Sep 15 Free Chicksands, Shefford SG17 5TQ Complete timetables are published Tel: 0300 3008078 Fax: 01234 228720 by Here To There Publishing Ltd * Loose-leaf, £35 inc postage * including Bedford and Luton Boroughs See the Links -

And Accounts

and Accounts 1 Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Annual Report and Accounts – 2010/11. Presented to parliament pursuant to Schedule 7, Paragraph 25 (4) of the National Health Service Act 2006. 2 3 Message from the Chairman and Chief Executive ............... 4 Message from the Medical Director .......................... 6 All about the organisation ................................. 8 Quality Accounts ....................................... 10 A Year of Quality ....................................... 11 Carbon Reduction ...................................... 46 Equality, Diversity & Human Rights ..........................48 Council of Governors .................................... 50 Membership ........................................... 62 Working with our staff. 66 Infection Prevention and Control ........................... 74 Performance against Trust business objectives 2010/11 .......... 76 Monitor’s Regulatory Ratings ...................................80 Working with our patients & visitors ........................ 82 Research and Innovation ................................. 86 Highlights and Developments .............................. 90 Contents Activity and Performance ................................. 98 Board of Directors ..................................... 100 Emergency Preparedness ................................ 107 Statement of Internal Control ............................. 108 Statement of Compliance with the NHS Foundation Trust Code of Governance ................................116 Audit -

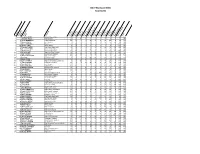

Bdoy 2016 Score Sheet with Names V2.Xlsx

1Posi 71tio Craign LOCKYER 2 2 Jonathan WELCH 3 98 Colin HENDERSON 4 12 Adam KSIAZEKCompetitor 5 1 Darren MARSHALL 6 115 Shaun CLARK Number 7 73 Timothy CLARKE 8 56 Steven WILLIAMS 9 77 Stephen BATE om tit r 10 44 Brian MACKIE C pe o 11 8 Neil COUSINS Name 12 11 William BRADFORD 13 27 Ed LOVE 14 65 Barry YOUNG 15 112 Lynne CORNECT 16 61 Gareth HUGHES 17 46 Tom BEATTIE 18 72 Steven McLEOD 19 83 Mark WOODGATE 20 89 John BLACK 21 101 Peter MASCALL 22 90 Ted REID 23 19 Georgina FISH 24 59 Ionut ARGINT 25 48 Stephen APPIAH 26 76 Luke TOWEY 27 81 David SWANEY 28 70 David HIND 29 41 Terry MILES 30 66 Paul JARVIS 31 6 Paul WALFORD 32 87 James EMBERSON National Express Bus 40 20 0 10 0 0 0 0 0 0 90 160 33 15 Jurijs KOROTKOVS First AberdeenCompany 20 20 50 10 10 0 0 0 0 0 60 170 34 93 Martyn SMITH First Scotland East 20 30 0 0 40 0 0 30 20 0 50 190 35 34 Martin PARKER First Aberdeen 0 10 0 10 20 0 0 20 10 50 80 200 36 69 David HODGES Morebus 10 30 0 10 20 0 0 0 0 0 130 200 37 80 Darren DUNBAR Ipswich Buses 0 10 0 10 40 0 0 0 0 0 140 200 38 100 Richard CADMAN First Greater Manchester 10 30 0 0 0 0 0 20 10 50 100 220 39 22 Jonathan PRIEST Oxford Bus Company 0 30 0 10 40 0 0 20 20 50 70 240 40 96 Andrew RAITT National Express Bus 40 30 0 10 10 0 0 0 10 50 100 250 41 40 Darren KELLY Stagecoach East Scotland 20 20 0 10 20 50 0 20 20 0 100 260 42 62 Matthew SALTER Bournemouth Transport 20 30 50 10 10 50 0 0 10 0 90 270 43 7 Darrell HADLAND Stagecoach London 40 20 0 10 0 0 0 0 0 50 150 270 44 86 Michael LEECH Reading Transport 0 10 0 20 30 50 0 10 0 0 150 270 45 103 Alec MITCHELL First Greater Manchester 40 40 0 60 10 0 0 10 10 0 110 280 46 85 Scott CROSBIE Brighton & Hove Bus & Coach Co. -

Guided Busway Leigh to Manchester Timetable

Guided busway leigh to manchester timetable Continue Schedule data from FirstVantage, October 1, 2020 contactless payment accepted lee-salford-Manchester Bus Rapid TransitA Vantage bus at the Newearth Road bus stop on theoverviewOwnerTransport bus section for Greater ManchesterLocaleLocWiganSalfordManchesterTranstrans TypeGui Driven Bus and Rapid Transit BusAnly Rider3 millionWebsiteTfGM - Bus Priority - Guide BuswayOperationBegan Operation3 April 2016Operator (s)First Greater ManchesterTechnicalSystem length22 km Lee-Salford-Manchester Bus Rapid Transit Scheme in Greater Manchester, England provides transport links between Lee , Atherton, Tyldesley, Ellenbrook and Manchester city centre via Salford. On 3 April 2016, the Rapid Transit Of Buses and Buses (BRT) scheme was launched, promoted by Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM). Built by Balfour Beatty, worth a total of 122 million pounds to improve links with former coal mining towns in Manchester city, the bus proposal faced much opposition and a public inquiry in 2002, before construction finally began in 2013. The branch route from Atherton and the extension to Manchester Royal Infirmary were added to the planned original scheme. Twenty-five purple-liveried Wright Eclipse Gemini 3 bodily Volvo B5LH hybrid two-story is equipped with CCTV and the next stop audio and visual ads run service. Stops on the section of operated bus tracks have a landing level from platforms equipped with screens displaying information about passengers. From Lee, the V1 bus, with a limited stop, connects the seven kilometres of the guide bus to Ellenbrook, the six kilometres of bus lanes on East Lancashire Road and sections of reserved bus lanes through Salford and Manchester centres. The V2 service from Atherton to Manchester connects to the bus track at Tildesley. -

Travelwatch Northwest Company No

1 Princess St Manchester: Tel 07807 768124 TravelWatch Email: [email protected] Website: www.travelwatch-northwest.org.uk Correspondence address – 11 Harvelin NORTHWEST Park, Todmorden, OL14 6HX Winner of CILT award for best practice in passenger transport promoting quality public transport.......... Photo Ian Watson Information about Bus Fares revisited March 2014 North West Public Transport Users’ Forum Community Interest Company trading as TravelWatch NorthWest Company No. 6181713 Registered Office: 11 Harvelin Park, Todmorden, Lancs OL14 6HX 2 Contents Page 1. Introduction and Background 3 2. Research Aims and Methodology 4 3. Survey Findings 5 4. Recommendations and Conclusion 9 Appendix – Survey Results North West Public Transport Users’ Forum Community Interest Company trading as TravelWatch NorthWest Company No. 6181713 Registered Office: 11 Harvelin Park, Todmorden, Lancs OL14 6HX 3 1. Introduction and Background 1.1 TravelWatch NorthWest (TWNW) dates back to October 2003 when the Rail Passengers Committee for North Western England (RPC), using its powers under section 228 of the Transport Act 2000, set up the North West Public Transport Users Forum (NWPTUF). This legislation required, inter alia, the RPC to co-operate with other bodies representing the interests of users of all public transport services. The RPC, alongside the North West Regional Assembly, identified a gap in the representation of public transport users across the region and across modes. Similar forums, now also under the TravelWatch banner, have been established in South West England, the West Midlands, the East Midlands and Southern England. With the demise of the regional RPCs TWNW has become an independent Community Interest Company limited by guarantee. -

Cross Reference of Fleet Names to Operator Titles April 2014 Edition

Cross Reference of Fleet Names to Operator Titles April 2014 Edition This listing provides a cross-reference of all fleet names to operator titles in the most recent round of G-Lists published by the PSV Circle. Each county or area is represented by the most recently issued G-List for that county. As at the date of publication, this list comprises references to G-Lists in both the 6 th (G5xx) and 7 th (G6xx) editions. This list is updated to G-Lists published in April 2014. Fleet Name Operator’s Title G-List 001 Minibuses Najeeb, Rotherham (SY) G671 001 Minibuses Tingey, Hemsworth (WY) G575-6 001 Taxibus Oxford Contract Vehicles, Oxford (OX) G633 01256 Minibuses Stoneman, Basingstoke (HA) G621 1 to 1 Community Transport Kelsey & Davies, North Benfleet (EX) G525-6 1-16 Minibuses Jackman, Newport Pagnell (BK) G653 1919 Minibuses Lee, Woodley (GM) G565-6 1919 Minibuses Normansell, Bredbury (GM) G565-6 1919 Minibuses Wallis, Woodley (GM) G565-6 1919 Minibuses Wilson, Romiley (GM) G565-6 1957 Executive Welch, Baguley (GM) G565-6 1st AAA Coaches Thurbin, Haverhill (SK) G556 1st American Limousines Clegg, Scunthorpe (LI) G553 1st AP Travel Coles, Totnes (DN) G631 1st Avenue Limousines Chambers, Billericay (EX) G525-6 1st Bus Stop Thurbin, Istead Rise (KT) G622-3 1st Call Limos Ramzan, Luton (BD) G651 1st Call Limos Ramzan, Luton (BD) G551 1st Call Minibuses Mason, Merthyr Tydfil (CS) G584 1st Call Minibuses Zahid, Nottingham (NG) G641 1st Call Fox, Birley Carr (SY) G671 1st Choice Limos Wright, Cottingham (EY) G572 1st Choice Limos Wright, Cottingham -

Palonen.Pdf (8.837Mt)

TUOMAS PALONEN TÄLLAISTA TULI TÄLLÄ RAHALLA – KAUPUNKILIIKENTEEN JÄRJESTÄMISTAVAN VAIKUTUS PALVELUTASOON Diplomityö Tarkastaja: Assistant Professor Heikki Liimatainen Tarkastaja ja aihe hyväksytty 25. syyskuuta 2017 i TIIVISTELMÄ TUOMAS PALONEN: Tällaista tuli tällä rahalla – Kaupunkiliikenteen järjestämistavan vaikutus palvelutasoon Tampereen teknillinen yliopisto Diplomityö, 98 sivua, 2 liitesivua Syyskuu 2017 Rakennustekniikan diplomi-insinöörin tutkinto-ohjelma Pääaine: Liikenne- ja kuljetusjärjestelmät Tarkastaja: Assistant Professor Heikki Liimatainen Avainsanat: joukkoliikenne, palvelutaso, kaupunkiliikenne, markkinaehtoisuus Kaupungit houkuttelevat enenevissä määrin lisää asukkaita, minkä seurauksena on tarve järjestää liikenne mahdollisimman toimivasti, ympäristöystävällisesti ja taloudellisesti. Joukkoliikenteellä voidaan vastata kasvavien kaupunkien liikenteen haasteisiin, mutta tehokkaan joukkoliikenteen järjestäminen myös maksaa kaupungeille. Suomessa on saatu hyviä kokemuksia pitkämatkaisen linja-autoliikenteen avaamisesta kilpailulle. Suosituilla reiteillä sekä kysyntä että tarjonta ovat lisääntyneet ja lippujen hinnat ovat alentuneet. Voisiko myös kaupunkien joukkoliikenne hyötyä markkinaehtoisuudesta? Suomessa kaupunkien joukkoliikenne on nykyään lähes kaikkialla toteutettu julkisen tahon organisoiman tilaaja-tuottaja-mallin mukaisesti. Tässä työssä vertailtiin tiettyjen Ison-Britannian, Sveitsin, Ruotsin ja Suomen kaupunkien joukkoliikennettä. Vertailun pohjalta pyrittiin muodostamaan näkemys siitä, mitä joukkoliikenteen