FROM JAPAN: Robert Carl’S Musical Reflection on History, Culture, and Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Piano Four-Hands 21:37 Donald Berman and John Mcdonald, Piano

pg 8 pg 1 1. SHAKE THE TREE (2005) for piano four-hands 21:37 Donald Berman and John McDonald, piano BRAIDED BAGATELLES (2001-02) 18:35 Moritz Eggert, piano 2. Cadenza 2:26 3. Marking the Field 2:38 4. Stretching 3:22 5. Marching 2:27 6. Floating 2:40 7. Flying 4:52 PIANO SONATA NO.2, “THE BIG ROOM” (1993-99) 27:05 Erberk Eryilmaz, piano 8. Clouds Are Scattering 6:16 9. The Big Room 9:05 10. The World Turned Upside Down 11:44 --67: 04-- pg 2 pg 7 My piano music is a continuing diary of my growth as a composer. And that’s Erberk Eryilmaz, a native of Turkey, is a composer, pianist, and conductor. He ironic, since I’m a very modest pianist. But starting with my first sonata, “Spi- completed his undergraduate studies at the Hartt School, University of Hartford, ral Dances” (1984), it’s been the medium where I can test out ideas big and and is currently pursuing graduate studies at Carnegie Mellon University. He is small, some very spacious and ambitious, others occasional, experimental, and a founder and co-director of the Hartford Independent Chamber Orchestra. lighter-hearted. The culmination of this approach is Shake the Tree, perhaps the most virtuosic and architecturally ambitious work I’ve ever written. Two of John McDonald is a composer who tries to play the piano and a pianist who its major predecessors are Braided Bagatelles, a bravura evocation of variation tries to compose. He is Professor of Music and Department Chair at Tufts Uni- form, mixed with elements that verge on Dada, and my Piano Sonata No. -

Rethinking Minimalism: at the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism

Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter Shelley A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee Jonathan Bernard, Chair Áine Heneghan Judy Tsou Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music Theory ©Copyright 2013 Peter Shelley University of Washington Abstract Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter James Shelley Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Jonathan Bernard Music Theory By now most scholars are fairly sure of what minimalism is. Even if they may be reluctant to offer a precise theory, and even if they may distrust canon formation, members of the informed public have a clear idea of who the central canonical minimalist composers were or are. Sitting front and center are always four white male Americans: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass. This dissertation negotiates with this received wisdom, challenging the stylistic coherence among these composers implied by the term minimalism and scrutinizing the presumed neutrality of their music. This dissertation is based in the acceptance of the aesthetic similarities between minimalist sculpture and music. Michael Fried’s essay “Art and Objecthood,” which occupies a central role in the history of minimalist sculptural criticism, serves as the point of departure for three excursions into minimalist music. The first excursion deals with the question of time in minimalism, arguing that, contrary to received wisdom, minimalist music is not always well understood as static or, in Jonathan Kramer’s terminology, vertical. The second excursion addresses anthropomorphism in minimalist music, borrowing from Fried’s concept of (bodily) presence. -

Temporal and Harmonic Concerns in the Music of Robert Carl

TEMPORAL AND HARMONIC CONCERNS IN THE MUSIC OF ROBERT CARL A THESIS IN Musicology Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC by DANIEL ERIC MOREL B.A., Bucknell University, 2003 B.A., Bucknell University, 2003 M.M., The Hartt School, University of Hartford, 2011 A.D., The Hartt School, University of Hartford, 2013 Kansas City, Missouri 2018 © 2018 DANIEL ERIC MOREL ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TEMPORAL AND HARMONIC CONCERNS IN THE MUSIC OF ROBERT CARL Daniel Eric Morel, Candidate for the Master of Music in Musicology University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2018 ABSTRACT Robert Carl is a composer-critic based in Hartford, Connecticut. His hyphenated career has involved creating, teaching, and commenting on music for the latter half of the twentieth century up to the present. Initially trained as a historian, Carl has maintained a keen interest in modern musical trends while developing his own distinct musical language. His music fuses stylistic and conceptual influences that bleed through aesthetic boundaries, making it difficult to label or associate with other composers. While the result is not a stereotypical postmodern pastiche of the past, his music does embrace a pluralism of historical and current methods in ways characteristic of a composer keenly interested in modern American culture. Moreover, Carl’s music relates to stylistic developments within late 20th and 21st century American art music. Studying his music helps reveal overall trends within contemporary American art music. This thesis introduces Robert Carl through a biographical sketch and examines the development of time-based and harmonic concerns within his works. -

Vol 18-2: Review of in C by Robert Carl

BOOK reviews ROBErt CARL TErry RILEY’S Ninth Symphony together represent the IN C significant music from the second half of the Twentieth Century? Malcom Gillies, editor of Oxford University Press, 2010 The Oxford University Press series Studies in By Mark Zuckerman Musical Genesis, Structure, and Interpretation, believes so, with composer Robert Carl’s Terry Riley’s In C (1964) is widely regarded as the ambitious, elegantly written book in the Studies in Musical Genesis, Structure, and Interpretation Studies in Musical Genesis, Structure, and Interpretation series, Terry Riley’s In C, making the case. very challenges it presents to “classical” music. seminalnquestionably thework founding work in of the minimalist canon. Its score He examines In C in the context of its era, its Uminimalism in musical composition, grounding in aesthetic practices and assump- Terry Riley’s In C (1964) challenges the stan- tions, its process of composition, presentation, Terry Riley’s isdards lean: of imagination, one intellect, andpage musical of music and about a page recording, and dissemination. By examining ingenuity to which “classical” music is held. Carl Its blurred boundary between structure the work’s significance through discussion with andOnly one pagea ofhalf score in length, of it containsperformance advice. The music performers, composers, theorists, and critics, neither specified instrumentation nor parts. Robert Carl explores how the work’s emerg- Its fifty-three motives are compact, presented and interpretation makes In C an intriguing ing performance practice has influenced our iswithout a anysequence counterpoint or evident form. of The 53 modules: numbered linear very ideas of what constitutes art music in the composer gave only spare instructions and no addition to such a series. -

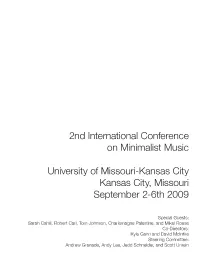

Conference Program

2nd International Conference on Minimalist Music University of Missouri-Kansas City Kansas City, Missouri September 2-6th 2009 Special Guests: Sarah Cahill, Robert Carl, Tom Johnson, Charlemagne Palestine, and Mikel Rouse Co-Directors: Kyle Gann and David McIntire Steering Committee: Andrew Granade, Andy Lee, Jedd Schneider, and Scott Unrein David Rosenboom James Tenney How Much Better if Plymouth Rock Had Spectrum Pieces Landed on the Pilgrims The Barton Workshop, David Rosenboom, Erika Duke-Kirkpatrick, Vinny Golia, James Fulkerson, musical director Swapan Chaudhuri, Aashish Khan, I Nyoman Wenten, 80692-2 [2 CDs] Daniel Rosenboom, and others 80689-2 [2 CDs] Larry Polansky Stuart Saunders Smith The Theory of Impossible Melody The Links Series of Jody Diamond, Chris Mann, voice; Phil Burk and Larry Polansky, live computers; Larry Polansky, electric guitar; Robin Vibraphone Essays Hayward, tuba 80690-2 [2 CDs] 80684-2 Io Jody Diamond Flute Music by Johanna Beyer, In That Bright World: Joan La Barbara, Larry Polansky, Music for Javanese Gamelan James Tenney, and Lois V Vierk Master Musicians at the Indonesian Margaret Lancaster, utes Institute of the Arts, Surakarta, Central Java, 80665-2 Indonesia; with Jody Diamond, voice 80698-2 Musica Elettronica Viva James Mulcro Drew MEV 40 (1967–2007) Animating Degree Zero Alvin Curran, Frederic Rzewski, Richard Teitelbaum, The Barton Workshop, Steve Lacy, Garrett List, George Lewis, Allan Bryant, James Fulkerson, musical director Carol Plantamura, Ivan Vandor, Gregory Reeve 80687-2 80675 (4 CDs) Robert Erickson Andrew Byrne Auroras White Bone Country Boston Modern Orchestra Project; Rafael Popper-Keizer, cello Stephen Gosling, piano; Gil Rose, conductor David Shively, percussion 80695-2 80696-2 The entire CRI CD catalog is now available as premium-quality on-demand CDs. -

In C and Beyond an Analysis of Four 21St Century Interpretations of Terry Riley’S in C (1964)

In C and beyond An analysis of four 21st century interpretations of Terry Riley’s In C (1964) Master Thesis Arts and Culture: Musicology Nora Kim Braams Student number: 6126170 Thursday July 19, 2018 Supervisor: Dr. M. Beirens University of Amsterdam Index Introduction 4 Chapter 1. - A brief history of minimal music 8 1.1. Musical minimalism 8 1.2. European serialism and indeterminacy 8 1.2.1. Morton Feldman and John Cage 9 1.2.2. Fluxus 9 1.3. Young, Riley, Reich and Glass 10 1.3.1. La Monte Young 10 1.3.2. Steve Reich 10 1.3.3. Philip Glass 11 1.4. Towards postminimalism 11 Chapter 2. - The life and music of Terry Riley 12 2.1. Early life and education 12 2.2. After San Francisco State University: 1958 – 1959 12 2.2.1. Young and Riley 13 2.3. Early works, tape music and looping techniques: 1960 – 1961 13 2.3.1. Envelope 13 2.3.2. String Trio 14 2.3.3. Mescalin Mix 14 2.4. Drugs, jazz and Europe 15 2.5. Last works before In C 15 2.5.1. Music of The Gift 15 2.5.2. Coule 16 2.6. Return to San Francisco: In C 16 2.6.1. The premiere of In C 17 2.7. After In C 18 Chapter 3. - Analysis: In C – the score and the guidelines 20 3.1. The score 20 3.2. The guidelines 20 2 3.3. Rhythmic vocabulary 22 3.4. Motivic transformations and rhythmic displacement 23 3.5. -

The Music of John Luther Adams / Edited by Bernd Herzogenrath

The Farthest Place * * * * * * * * * The Farthest Place The Music of John Luther �dams Edited by Bernd Herzogenrath � Northeastern University Press Boston northeastern university press An imprint of University Press of New England www.upne.com © 2012 Northeastern University All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Designed by Eric M. Brooks Typeset in Arnhem and Aeonis by Passumpsic Publishing University Press of New England is a member of the Green Press Initiative. The paper used in this book meets their minimum requirement for recycled paper. For permission to reproduce any of the material in this book, contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Suite 250, Lebanon NH 03766; or visit www.upne.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The farthest place: the music of John Luther Adams / edited by Bernd Herzogenrath. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-1-55553-762-3 (cloth: alk. paper)— isbn 978-1-55553-763-0 (pbk.: alk. paper)— isbn 978-1-55553-764-7 1. Adams, John Luther, 1953– —Analysis, appreciation. I. Herzogenrath, Bernd, 1964–. ml410.a2333f37 2011 780.92—dc23 2011040642 5 4 3 2 1 * For Frank and Janna Contents Acknowledgments * ix Introduction * 1 bernd herzogenrath 1 Song of the Earth * 13 alex ross 2 Music as Place, Place as Music The Sonic Geography of John Luther Adams * 23 sabine feisst 3 Time at the End of the World The Orchestral Tetralogy of John Luther Adams * 48 kyle gann 4 for Lou Harrison * 70 peter garland 5 Strange Noise, Sacred -

Robert Carl: White Heron What’S Underfoot | Rocking Chair Serenade | Symphony No

ROBERT CARL: WHITE HERON WHAT’S UNDERFOOT | ROCKING CHAIR SERENADE | SYMPHONY NO. 5 “LAND” [1] WHITE HERON (2012) 9:00 ROBERT CARL b. 1954 [2] WHAT’S UNDERFOOT (2016) 16:13 WHITE HERON [3] ROCKING CHAIR SERENADE FOR STRING ORCHESTRA (2013) 12:36 WHAT’S UNDERFOOT SYMPHONY NO. 5, “LAND” (2013) [4] I. Open Prairie 3:04 ROCKING CHAIR SERENADE [5] II. High Plains 5:40 [6] III. A. Facing Mountains 12:17 SYMPHONY NO. 5, “LAND” [7] III. B.1 Shimmering Mists 1:43 [8] III. B.2 Wildflower Meadow 2:52 BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT [9] III. B.3 Storm Fronts 0:29 Gil Rose, conductor [10] III. C. Scaling 0:48 [11] IV. Above the Tree Line 1:54 [12] V. Land Beyond 3:15 TOTAL 59:52 COMMENT By Robert Carl The works on this program all deal with space. It can be concrete/geographical. Symphony No.5, “Land”, comes from the experience of driving across the American midland from the Great Plains to the Rocky Mountains above the treeline. White Heron emerges from close observation of avian wildlife in the Florida Keys. Rocking Chair Serenade is an elegy to soft front-porch conversation and communion in the Appalachian Mountains, both of my youth and the site of its premiere. But they also deal with a more metaphorical space, that in which the sounds resonate. For the past two decades I’ve been exploring a personalized harmony in all my pieces, one that is modeled on the harmonic series. By creating vertical “ladders” of the twelve chromatic pitches—voiced similarly to the series, and based on different fundamentals—I’ve been able to create a “resonant space” in the music. -

Concerts Receive Support in 2018 From: Private Donors; the Robert Salzer Foundation; the William Angliss Trust; Diana Gibson

A S T R A C O N C E R T S 2 0 1 8 5 pm, Sunday 10 June CARMELITE CHURCH Middle Park, Melbourne FOR ALL SEASONS Charles Ives FAR O’ER YON HORIZON Keith Humble THUS SAITH THE LORD John J. Becker OUR MOUTH… Robert Carl SWEEPING EAGLE, BLITHE SWAN, BRANCHING OAK WINDING STREAM, DRIFTING CLOUDS COURSING SUN, IT IS THE LAW John J. Becker I TOUCH YOU, YOU QUIVER, KYRIE, SANCTUS Keith Humble FOUR ALL SEASONS Donald Martino I GO WHERE I DO KNOW INFINITIE TO DWELL String Quartet Natasha Conrau, Zachary Johnston, Phoebe Green, Alister Barker The Astra Choir with soloists and instrumental ensemble Natasha Conroy violin, Zachary Johnston violin, Phoebe Green viola, Alister Barker cello Nic Synot double bass, Kim Bastin organ, piano, Calvin Bowman organ vocal soloists Catrina Seiffert, Leonie Thomson, Louisa Billeter Spencer Chapman, Ben Owen, Steven Hodgson, Tim Matthews-Staindl The Astra Choir soprano Julie Melbourne, Irene McGinnigle, Catrina Seiffert, Kim Tan, Leonie Thomson, Jenny Barnes, Louisa Billeter, Jean Evans, Maree Macmillan, Susannah Provan alto Emily Bennett, Gloria Gamboz, Anna Gifford, Katie Richardson, Florence Thomson, Beverley Bencina, Jane Cousens, Joy Lee, Joan Pollock, Aline Scott-Maxwell tenor Spencer Chapman, Stephen Creese, Ben Owen, Richard Webb, Greg Deakin, Simon Johnson, Dylan Nicholson bass Peter Dumsday, Robert Franzke, Steven Hodgson, Tim Matthews-Staindl, Chris Smith, John Terrell, John Mark Williams John McCaughey conductor In Australia as in other countries, a generation of composers born in the 1920s rose to prominence in the 1960s as the voice of post-war music, joined by younger arrivals in generating the musical heritage of the late century. -

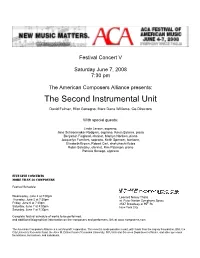

The Second Instrumental Unit

Festival Concert V Saturday June 7, 2008 7:30 pm The American Composers Alliance presents: The Second Instrumental Unit David Fulmer, Eliot Gattegno, Marc Dana Williams, Co-Directors With special guests: Linda Larson, soprano, Jane Schoonmaker-Rodgers, soprano, Kevin Bylsma, piano Benjamin Fingland, clarinet, Marilyn Nonken, piano Jacquelyn Familant, soprano, Keith Spencer, baritone, Elizabeth Brown, Robert Carl, shakuhachi flutes Robin Seletsky, clarinet, Kim Paterson, piano Patricia Sonego, soprano FIVE LIVE CONCERTS MORE THAN 30 COMPOSERS Festival Schedule: Wednesday, June 4 at 7:30pm Leonard Nimoy Thalia Thursday, June 5 at 7:30pm at Peter Norton Symphony Space Friday, June 6 at 7:30pm 2537 Broadway at 95th St. Saturday, June 7 at 4:00pm New York City Saturday, June 7 at 7:30pm Complete festival schedule of works to be performed, and additional biographical information on the composers and performers, link at www.composers.com The American Composers Alliance is a not-for-profit corporation. This event is made possible in part, with funds from the Argosy Foundation, BMI, the City University Research Fund, the Alice M. Ditson Fund of Columbia University, NYU Arts and Sciences Department of Music, and other generous foundations, businesses, and individuals. The Second Instrumental Unit David Fulmer, Eliot Gattegno, Marc Dana Williams, Co-Directors New York Women Composers, Inc. All performers from the Second Instrumental Unit unless otherwise noted. Marc Dana Williams, conductor Raoul Pleskow Piece for Eight Instruments (2007) * Joel Gressel An Orderly Transition (1985, rev. 2007) Linda Larson, soprano Burton Beerman Dialogue (2008) * Jane Schoonmaker-Rodgers, soprano Kevin Bylsma, piano ‡ Richard Cameron-Wolfe A Measure of Love and Silence (2006) Jacquelyn Familant, soprano Keith Spencer, baritone Intermission Hubert S. -

Robert Carl's Music for Strings

The Quest to Escape Chaos: Robert Carl’s Music for Strings Robert Carl possesses one of the widest and most varied expressive ranges of any composer of his generation. This isn’t the disc to prove that, however. In the string music here we focus in on what I think of as the central core of Carl’s aesthetic: the devoutly ruminative music with expression markings like “achingly” and “fragile.” In his string music, Carl aligns himself with Beethoven and Ives as a composer who asks musical questions, who frankly frames his own spiritual journey in sounds with all its doubts, hungers, epiphanies, and acquiescences. At the end of Open or Carl’s Second String Quartet, we know the composer’s response to the existential questions of life as definitively as we can know them at the end of Ives’s Fourth Symphony, or Beethoven’s Ninth. Carl can be playful, satirical, intellectual, or picturesque in his other works, but something about the soulful nature of strings makes him express his innermost yearnings through them. And these three works, written within a three-year period, are even more closely related than this implies. Their motivic material seems to be cut from the same cloth: the imperious dotted-rhythm motive at the beginning of Open, the thirds encircling each other in the “Angel-Skating” Sonata, the leaping lines at the beginning of the Second Quartet, are all based on pairs of interlocking intervals, whose contours Carl weaves into tapestries whose underlying unity is felt viscerally without being analytically contrived. Carl is a master at sustaining an idea without seeming to do so. -

Integrating the Postmodern Avant-Garde: Art Music(S) at the Intersection of Improvisation

Integrating the Postmodern Avant-Garde: Art Music(s) at the Intersection of Improvisation By © 2018 Kevin Todd Fullerton M.M., University of South Dakota, 2007 M.M., University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2002 B.A., Iowa State University, 2000 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Musicology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________________ Chair: Roberta Freund Schwartz _________________________ Colin Roust _________________________ Alan Street _________________________ Dan Gailey _________________________ Sherrie Tucker Date Defended: March 8, 2018 The dissertation committee for Kevin Fullerton certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Integrating the Postmodern Avant-Garde: Art Music(s) at the Intersection of Improvisation ______________________________ Chair: Roberta Freund Schwartz Date Approved: April 18, 2018 ii ABSTRACT In the wake of World War II, American artists and musicians participated in a cultural shift, with dramatic consequences. Musicians and artists engaged with postmodernism through experimentation. They were searching for new possibilities, creating a work that consists of a “field of relation,” or a framework, from which the artist improvises. I posit that avant-garde jazz and avant-garde classical music were not as separate, as they are most often regarded, but a single impulse concerned with expression of intuitive, process-oriented music that grew from a few examples in the first half of the century to a true movement of American experimentalism in the 1950s. Considering composers such as John Cage, Earle Brown, and Morton Feldman alongside Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Charles Mingus, and Sun Ra enriches our understanding of the experimental impulse.