Interview with Courtland Cox May 14, 1979 Camera Rolls: 6-9 Sound Rolls: 4-5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF Mourns the Loss of the Honora

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF mourns the loss of The Honorable John Lewis, an esteemed member of Congress and revered civil rights icon with whom our organization has a deeply personal history. Mr. Lewis passed away on July 17, 2020, following a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 80 years old. “I don’t know of another leader in this country with the moral standing of Rep. John Lewis. His life and work helped shape the best of our national identity,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, LDF’s President & Director-Counsel. “We revered him not only for his work and sacrifices during the Civil Rights Movement, but because of his unending, stubborn, brilliant determination to press for justice and equality in this country. “There was no cynicism in John Lewis; no hint of despair even in the darkest moments. Instead, he showed up relentlessly with commitment and determination - but also love, and joy and unwavering dedication to the principles of non-violence. He spoke up and sat-in and stood on the front lines – and risked it all. This country – every single person in this country – owes a debt of gratitude to John Lewis that we can only begin to repay by following his demand that we do more as citizens. That we ‘get in the way.’ That we ‘speak out when we see injustice’ and that we keep our ‘eyes on the prize.’” The son of sharecroppers, Mr. Lewis was born on Feb. 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama. He grew up attending segregated public schools in the state’s Pike County and, as a boy, was inspired by the work of civil rights activists, including Dr. -

Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information

“The Top Ten” Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information (Asa) Philip Randolph • Director of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. • He was born on April 15, 1889 in Crescent City, Florida. He was 74 years old at the time of the March. • As a young boy, he would recite sermons, imitating his father who was a minister. He was the valedictorian, the student with the highest rank, who spoke at his high school graduation. • He grew up during a time of intense violence and injustice against African Americans. • As a young man, he organized workers so that they could be treated more fairly, receiving better wages and better working conditions. He believed that black and white working people should join together to fight for better jobs and pay. • With his friend, Chandler Owen, he created The Messenger, a magazine for the black community. The articles expressed strong opinions, such as African Americans should not go to war if they have to be segregated in the military. • Randolph was asked to organize black workers for the Pullman Company, a railway company. He became head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first black labor union. Labor unions are organizations that fight for workers’ rights. Sleeping car porters were people who served food on trains, prepared beds, and attended train passengers. • He planned a large demonstration in 1941 that would bring 10,000 African Americans to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC to try to get better jobs and pay. The plan convinced President Roosevelt to take action. -

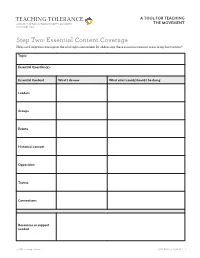

Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How Can I Improve Coverage of the Civil Rights Movement by Addressing These Essential Content Areas in My Instruction?

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: Essential Question(s): Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should I be doing Leaders Groups Events Historical context Opposition Tactics Connections Resources or support needed © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage (SAMPLE) How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should be doing Leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, James Farmer, John Lewis, Roy A. Philip Randolph Wilkins, Whitney Young, Dorothy Height Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Student Nonviolent Groups Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), National Urban League (NUL), Negro American Labor Council (NALC) The 1963 March on Washington was one of the most visible and influential Some 250,000 people were present for the March Events events of the civil rights movement. Martin Luther on Washington. They marched from the Washington King Jr. -

JEWS and the CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

ENTREE: A PICTURE WORTH A THOUSAND NARRATIVES JEWS and the FRAMING A picture may be worth a thousand words, but it’s often never quite as CIVIL RIGHTS simple as it seems. Begin by viewing the photo below and discussing some of the questions that follow. We recommend sharing more MOVEMENT background on the photo after an initial discussion. APPETIZER: RACIAL JUSTICE JOURNEY INSTRUCTIONS Begin by reflecting on the following two questions. When and how did you first become aware of race? Think about your family, where you lived growing up, who your friends were, your viewing of media, or different models of leadership. Where are you coming from in your racial justice journey? Please share one or two brief experiences. Photo Courtesy: Associated Press Once you’ve had a moment to reflect, share your thoughts around the table with the other guests. GUIDING QUESTIONS 1. What and whom do you see in this photograph? Whom do you recognize, if anyone? 2. If you’ve seen this photograph before, where and when have you seen it? What was your reaction to it? 3. What feelings does this photograph evoke for you? 01 JEWS and the CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT BACKGROUND ON THE PHOTO INSTRUCTIONS This photograph was taken on March 21, 1965 as the Read the following texts that challenge and complicate the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. marched with others from photograph and these narratives. Afterwards, find a chevruta (a Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in support of voting partner) and select several of the texts to think about together. -

1 John Lewis: a Conversation – Marching for Freedom

1 JOHN LEWIS: A CONVERSATION – MARCHING FOR FREEDOM CLOSED CAPTIONING SCRIPT Hoffman: Congressman John Lewis, I am so glad you’re here for this conversation. I’ve looked so forward to meeting you and --again I appreciate your time. Lewis: Well, I’m delighted and very pleased to be here. Susan, thank you for having me here. Hoffman: Over the next half hour my goal is to cover your pivotal role in the Civil Right Movement. I’d like you to begin with me here. In 1963, when you were 23, you were listed as one of the six primary leaders in the Civil Rights Movement. And I wonder, did you feel at 23 that you were ready for that awesome responsibility. Lewis: Well, at the age of 23, I had grown up a little. You must understand that I grew up in rural Alabama, fifty miles from Montgomery, and I came under the influence of Martin Luther King, Jr. I heard Dr. King’s voice. I heard his words on an old radio. I’d heard about Rosa Parks and T Montgomery Bus Boycott. I’d seen segregation. I’d seen racial discrimination. Hoffman: Describe those early signs that you remember as a young boy. Lewis: Well I saw the signs that said “White Men,” “Colored Men,” “White Women,” “Colored Women,” “White Waiting,” “Colored Waiting.” I didn’t like it. As a child, I would ask my mother, my father, my grandparents, my great-grandparents, “Why segregation? Why racial discrimination?” And they would say, “That’s the way it is. -

Inspired by Gandhi and the Power of Nonviolence: African American

Inspired by Gandhi and the Power of Nonviolence: African American Gandhians Sue Bailey and Howard Thurman Howard Thurman (1899–1981) was a prominent theologian and civil rights leader who served as a spiritual mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr. Sue Bailey Thurman, (1903–1996) was an American author, lecturer, historian and civil rights activist. In 1934, Howard and Sue Thurman, were invited to join the Christian Pilgrimage of Friendship to India, where they met with Mahatma Gandhi. When Thurman asked Gandhi what message he should take back to the United States, Gandhi said he regretted not having made nonviolence more visible worldwide and famously remarked, "It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world." In 1944, Thurman left his tenured position at Howard to help the Fellowship of Reconciliation establish the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco. He initially served as co-pastor with a white minister, Dr. Alfred Fisk. Many of those in congregation were African Americans who had migrated to San Francisco for jobs in the defense industry. This was the first major interracial, interdenominational church in the United States. “It is to love people when they are your enemy, to forgive people when they seek to destroy your life… This gives Mahatma Gandhi a place along side all of the great redeemers of the human race. There is a striking similarity between him and Jesus….” Howard Thurman Source: Howard Thurman; Thurman Papers, Volume 3; “Eulogy for Mahatma Gandhi:” February 1, 1948; pp. 260 Benjamin Mays (1894–1984) -was a Baptist minister, civil rights leader, and a distinguished Atlanta educator, who served as president of Morehouse College from 1940 to 1967. -

John Lewis Chronological Timeline

“The Beloved Community is nothing less than the Christian concept of the Kingdom of God on earth. According to this concept, all human existence throughout history, from Ancient Eastern and Western societies up through the present day, has strived toward community, toward coming together. That movement is as inexorable, as irresistible, as the flow of a river toward the sea.” Representative, John Lewis John Lewis Chronological Timeline Born in rural Alabama during the dark days of Jim Crow segregation, Rep. John Lewis rose from poverty to become a leader of the civil rights movement and later was elected to Congress. Here is a timeline of some major events in Lewis’ life. Feb. 21, 1940: Born the son of Black sharecroppers near Troy, Alabama. Living in an isolated rural area, Lewis and his family can only manage to attend church two miles away from home one Sunday a month. But his mother reads to him from the Bible on a regular basis. From a very early age, Lewis is drawn to the “sweep and scope” of the Christian story – from the story of God’s creation through the arrival of Jesus to “take away the sins of the world.” Summer 1945: Lewis is given responsibility for taking care of the chickens on his parents’ farm. He begins administering to his flock and honing his preaching skills. 1951: Leaving the proximity of his home for the first time, Lewis learns first-hand the realities of segregation in the South. Bused 8 miles to jr. high school, he notices how blacks are treated differently than whites – unpaved roads, dilapidated school busses, separate drinking fountains for blacks and whites. -

Class Copy a Commitment to Nonviolence: the Leadership of John Lewis

Class Copy A Commitment to Nonviolence: The Leadership of John Lewis The Civil Rights Movement produced many African American heroes. Among those at the top of this list is John Lewis, who as a young student led the Nashville Student Movement in 1960. Using nonviolence and civil disobedience as their tools, Lewis and other courageous African Americans organized a series of sit-ins to demonstrate for the desegregation of Nashville. During these campaigns, he was often harassed and beaten but always stood firm in his adherence to nonviolent social action. Lewis became a major figure of the Civil Rights Movement and was elected chairperson of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1963. Since 1987, Lewis has served in the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1998, Lewis published his memoirs, Walking With the Wind, in which he recalls his years as a key participant in the historic struggles for civil rights. In the following excerpt, Lewis remembers the first Nashville sit-in he helped organize in February 1960. Walking With the Wind an excerpt by John Lewis I went back to First Baptist during that Christmas 1996 visit and found nothing but a gravel parking lot where the church used to be and a plaque telling passersby that this was where Kelly Miller Smith's church once stood, the site where the Nashville sit-ins began. The church was razed in 1972 and rebuilt about a quarter mile down the hill. A low-slung modern building, the new sanctuary sits today near the interstate and the railroad tracks. On a Friday morning I could hear the rumble and clanks of a passing freight train as I walked through the front doors. -

John Lewis US Congressman, Civil Rights Activist “Never, Ever Be Afraid to Make Some Noise and Get in Good Trouble, Necessary Trouble.” Page | 1

Educating For Democracy PROFILE OF RESISTANCE John Lewis US Congressman, civil rights activist “Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.” Page | 1 Background Information Born: February 21, 1940- Died July 17th, 2020 John Lewis was born in Troy, Alabama. His parents were sharecroppers. Lewis studied at American Baptist College and Fisk University. While he was in college, he learned about non- violent protesting. After graduation, Lewis led the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Courtesy of @repjohnjewis/ Twitter Lewis’s Resistance John Lewis was a leader in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. He fought against the segregation in the southern states. Lewis and his friends would have “sit ins” at White-only restaurants in Nashville, Tennessee. They would go to restaurants that excluded Black people, and try to order food. Lewis and his friends were arrested and sent to jail for the sit- ins. Even when the police attacked Lewis, he did not respond with violence. He worked with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to organize the March on Washington, where MLK gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Lewis was the youngest speaker at the 1963 March on Washington, and remains the only living speaker from that day. 1 Lewis also led peaceful marches in Selma, Alabama. Lewis was a leader of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In 1964, Lewis and other members of SNCC opened freedom schools in Mississippi. Freedom schools provided education and training for Black children in the south. Lewis also organized bus boycotts, student sit-ins, and nonviolent protests. -

FCA Shares Video Interview with Congressman John Lewis

Farm Credit Administration News Release 1501 Farm Credit Drive McLean, VA 22102-5090 For Immediate Release Contact: Mike Stokke or Emily Yaghmour, NR 20-12 (07-20-20) 703-883-4056 Email: [email protected] FCA shares video interview with Congressman John Lewis McLEAN, Va., July 20, 2020 — Congressman John Lewis of Georgia passed away on Friday, July 17, at the age of 80. In honor of his memory, the Farm Credit Administration shares a 15-minute video interview with Congressman Lewis conducted by FCA’s late chairman Kenneth A. Spearman, the first African American to head a U.S. federal bank regulator. The video, titled “The Sharecroppers’ Son,” was made in March 2016, not long before Chairman Spearman’s death. In the interview, the two men discussed a range of topics, from the congressman’s childhood in rural Alabama, to the future of civil rights. Congressman Lewis described the segregation and racial discrimination he had seen as a child. “When we visited the little town of Troy, I saw the signs that said white and colored,” he said. “And the schools were all segregated. Our school bus was old, ragged, broken down. We’d pass the white school and we’d see the little white children get on the new buses and enter the beautiful, well-painted schools. And I kept on asking my mother and my father, my grandparents, and my great-grandparents, ‘Why? Why?’ “And they would say, ‘That’s the way it is! That’s the way it is! Don’t get in the way. -

Handout Two: Leadership Influences

HANDOUT TWO: LEADERSHIP INFLUENCES JUSTICE THURGOOD MARSHALL Justice Thurgood Marshall was one of the most influential and important legal minds and lawyers in 20th century America, and for Bryan Stevenson, he was a legal inspiration. Born in Baltimore, Maryland on July 2, 1908, Justice Marshall was the grandson of an enslaved person who became the first African American to be appointed to the United States Supreme Court. After completing high school in 1925, he graduated from Lincoln University in Chester County, Pennsylvania. In 1930, he applied to the University of Maryland Law School, but was denied admission because he was African American. He sought admission and was accepted to Howard University Law School (HULS). In 1933 Justice Marshall graduated as valedictorian of HULS and starting in 1938, he worked as an attorney for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP.) In 1940, he became their chief counsel and founder of the NAACP I think it [Brown v. Board] Legal Defense and Educational Fund from 1934 - 1961. Justice Marshall argued thirty-two cases in front of the U.S. Supreme mobilized African-Americans Court, more than any other American in history, creating a in ways that made the number of precedents leading to Brown v. Board of Education Montgomery bus boycott (1954) that overruled Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and stated and all the civil rights that “separate by equal” was unconstitutional in public schools activism that you saw nationwide.2 throughout the 50s and 60s possible. There had to In 1961, President John F. Kennedy appointed Justice Marshall to be some ally in an effort the U.S. -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced individual views toward women one of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965.