American Chinese Medicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Flexner Report ― 100 Years Later

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central YAlE JOuRNAl OF BiOlOGY AND MEDiCiNE 84 (2011), pp.269-276. Copyright © 2011. HiSTORiCAl PERSPECTivES iN MEDiCAl EDuCATiON The Flexner Report ― 100 Years Later Thomas P. Duffy, MD Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut The Flexner Report of 1910 transformed the nature and process of medical education in America with a resulting elimination of proprietary schools and the establishment of the bio - medical model as the gold standard of medical training. This transformation occurred in the aftermath of the report, which embraced scientific knowledge and its advancement as the defining ethos of a modern physician. Such an orientation had its origins in the enchant - ment with German medical education that was spurred by the exposure of American edu - cators and physicians at the turn of the century to the university medical schools of Europe. American medicine profited immeasurably from the scientific advances that this system al - lowed, but the hyper-rational system of German science created an imbalance in the art and science of medicine. A catching-up is under way to realign the professional commit - ment of the physician with a revision of medical education to achieve that purpose. In the middle of the 17th century, an cathedrals resonated with Willis’s delin - extraordinary group of scientists and natu - eation of the structure and function of the ral philosophers coalesced as the Oxford brain [1]. Circle and created a scientific revolution in the study and understanding of the brain THE HOPKINS CIRCLE and consciousness. -

Newsletteralumni News of the Newyork-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Department of Surgery Volume 12, Number 2 Winter 2009

NEWSLETTERAlumni News of the NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Department of Surgery Volume 12, Number 2 Winter 2009 Virginia Kneeland Frantz and 20th Century Surgical Pathology at Columbia University’s College of Physicians & Surgeons and the Presbyterian Hospital in the City of New York Marianne Wolff and James G. Chandler Virginia Kneeland was born on November 13, 1896 into a at the North East corner of East 70th Street and Madison Avenue. family residing in the Murray Hill district of Manhattan who also Miss Kneeland would receive her primary and secondary education owned and operated a dairy farm in Vermont.1 Her father, Yale at private schools on Manhattan’s East Side and enter Bryn Mawr Kneeland, was very successful in the grain business. Her mother, College in 1914, just 3 months after the Serbian assassination of Aus- Anna Ball Kneeland, would one day become a member of the Board tro-Hungarian, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which ignited the Great of Managers of the Presbyterian Hospital, which, at the time of her War in Europe. daughter’s birth, had been caring for the sick and injured for 24 years In November of 1896, the College of Physicians and Surgeons graduated second in their class behind Marjorie F. Murray who was (P&S) was well settled on West 59th Street, between 9th and 10th destined to become Pediatrician-in-Chief at Mary Imogene Bassett (Amsterdam) Avenues, flush with new assets and 5 years into a long- Hospital in 1928. sought affiliation with Columbia College.2 In the late 1880s, Vander- Virginia Frantz became the first woman ever to be accepted bilt family munificence had provided P&S with a new classrooms into Presbyterian Hospital’s two year surgical internship. -

The Web That Has No Weaver

THE WEB THAT HAS NO WEAVER Understanding Chinese Medicine “The Web That Has No Weaver opens the great door of understanding to the profoundness of Chinese medicine.” —People’s Daily, Beijing, China “The Web That Has No Weaver with its manifold merits … is a successful introduction to Chinese medicine. We recommend it to our colleagues in China.” —Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China “Ted Kaptchuk’s book [has] something for practically everyone . Kaptchuk, himself an extraordinary combination of elements, is a thinker whose writing is more accessible than that of Joseph Needham or Manfred Porkert with no less scholarship. There is more here to think about, chew over, ponder or reflect upon than you are liable to find elsewhere. This may sound like a rave review: it is.” —Journal of Traditional Acupuncture “The Web That Has No Weaver is an encyclopedia of how to tell from the Eastern perspective ‘what is wrong.’” —Larry Dossey, author of Space, Time, and Medicine “Valuable as a compendium of traditional Chinese medical doctrine.” —Joseph Needham, author of Science and Civilization in China “The only approximation for authenticity is The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, and this will take readers much further.” —The Kirkus Reviews “Kaptchuk has become a lyricist for the art of healing. And the more he tells us about traditional Chinese medicine, the more clearly we see the link between philosophy, art, and the physician’s craft.” —Houston Chronicle “Ted Kaptchuk’s book was inspirational in the development of my acupuncture practice and gave me a deep understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. -

47 Practice. Prerequisite: AC211, AC311; May Be Taken Concurrently

Comprehensive Exam II, (the graduation exam) evaluates a student's academic readiness to graduate and provides the student with exposure to an examination process that simulates an examination like the California State Licensure examinations. A student who fails the Graduation exam twice should meet with the Dean for academic advice. If they take additional courses Federal Student Aid is NOT available for this remediation. MSTCM Course Descriptions Acupuncture AC211 Acupuncture I (4.0 units) Acupuncture, a core part of traditional Chinese medicine, consists of 6 courses and provides students with a thorough theoretical and practical knowledge of meridian theory and modern clinical applications of traditional Chinese acupuncture. The courses comprise an introduction of meridian theory, point location, functions and indications, different types of needle manipulation, therapeutic techniques and equipment, clinical strategies and methodologies in acupuncture treatment. Acupuncture I covers the history of acupuncture and moxibustion, meridian theory, basic point theory, point location, functions and indications of the first 6 channels (the lung channel of hand Taiyin, the large intestine channel of hand Yangming, the stomach channel of foot Yangming, the spleen channel of foot Taiyin, the heart channel of the hand Shaoyin, and the small intestine channel of hand Taiyang). The lab sessions focus on accurate point locations for each of these channels. Prerequisite: None AC311 Acupuncture II (4.0 units) Acupuncture II covers point location, functions and indications of the eight remaining channels: the urinary bladder channel of foot Taiyang, the kidney channel of foot Shaoyin, the pericardium channel of hand Jueyin, the triple burner channel (San Jiao) of hand Shaoyang, the gall bladder channel of foot Shaoyang, the liver channel of hand Jueying, the Ren (Conception) channel and the Du (Governing) channel. -

From Yellow Peril to Model Minority : ǂb Deconstruction of the Model Minority Myth and Implications for the Invisibility of Asian American Mental Health Needs

Smith ScholarWorks Theses, Dissertations, and Projects 2017 From yellow peril to model minority : ǂb deconstruction of the model minority myth and implications for the invisibility of Asian American mental health needs Lynda Anne Moy Smith College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Moy, Lynda Anne, "From yellow peril to model minority : ǂb deconstruction of the model minority myth and implications for the invisibility of Asian American mental health needs" (2017). Masters Thesis, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/1909 This Masters Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lynda Anne Moy From Yellow Peril to Model Minority: Deconstruction of the Model Minority Myth and Implications for the Invisibility of Asian American Mental Health Needs ABSTRACT The model minority myth is a racial stereotype imposed upon Asian Americans, often depicting them as a successful and high-achieving monolithic group in the United States. This paper examines sociopolitical functions of the term “model minority” and implications for this broad and diverse racial group by reviewing existing literature and conducting an analysis of qualitative interviews with 12 Asian Americans. The findings of this study suggest that while the model minority myth appears to be a positive stereotype, it may lead Asian Americans to experience distress through (a.) a sense of confinement, (b.) treatment as foreigners, and (c.) erasure and invisibility of challenges around identity, racism and discrimination, immigrant and refugee experiences, mental health, and accessing culturally sensitive resources. -

Energy Healing

57618_CH03_Pass2.QXD 10/30/08 1:19 PM Page 61 © Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION. CHAPTER 3 Energy Healing Our remedies oft in ourselves do lie. —WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Describe the types of energy. 2. Explain the universal energy field (UEF). 3. Explain the human energy field (HEF). 4. Describe the seven auric layers. 5. Describe the seven chakras. 6. Define the concept of energy healing. 7. Describe various types of energy healing. INTRODUCTION For centuries, traditional healers worldwide have practiced methods of energy healing, viewing the body as a complex energy system with energy flowing through or over its surface (Rakel, 2007). Until recently, the Western world largely ignored the Eastern interpretation of humans as energy beings. However, times have changed dramatically and an exciting and promising new branch of academic inquiry and clinical research is opening in the area of energy healing (Oschman, 2000; Trivieri & Anderson, 2002). Scientists and energy therapists around the world have made discoveries that will forever alter our picture of human energetics. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is conducting research in areas such as energy healing and prayer, and major U.S. academic institutions are conducting large clinical trials in these areas. Approaches in exploring the concepts of life force and healing energy that previously appeared to compete or conflict have now been found to support each other. Conner and Koithan (2006) note 61 57618_CH03_Pass2.QXD 10/30/08 1:19 PM Page 62 © Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION. 62 CHAPTER 3 • ENERGY HEALING that “with increased recognition and federal funding for energetic healing, there is a growing body of research that supports the use of energetic healing interventions with patients” (p. -

New York College Of

New York College of TraditionalAcupuncture & Oriental Medicine Chinese Degree Programs Medicine New York College of Traditional Chinese Medicine Acupuncture & Oriental Medicine Degree Programs Catalog 2017 - 2018 New York College of Traditional Chinese Medicine 200 Old Country Road Suite 500 Mineola, NY 11501 T: 516.739.1545 F: 516.873.9622 Manhattan Auxilliary 13 E. 37th Street, 4th Floor New York, NY 10016 T: 212.685.0888 F: 212.685.1883 For More Information Please visit us at www.nyctcm.edu You can also call us at 516.739.1545 or email [email protected] © New York College of Traditional Chinese Medicine. All rights reserved 2017-2018. New York College of Traditional Chinese Medicine Table of Contents About NYCTCM .....................................6 Selection of Candidates & Notification of Admission ............42 History .................................................................................6 Student Services .....................................43 NYCTCM is Unique ........................................................6 Student Services .................................................................43 Educational Objectives .......................................................7 Financial Information ............................44 Programs .............................................................................7 NYCTCM Tuition .............................................................44 Administration ....................................................................8 Tuition Payment Policy .......................................................44 -

Chinese Massacre of 1871?

CURRICULUM PROJECT HISTORICAL INQUIRY QUESTION What were the causes of the Anti- Chinese Massacre of 1871? LOST LA EPISODE Wild West What were the causes of the Anti- Chinese Massacre of 1871? Author of Lesson Miguel Sandoval Animo Pat Brown Charter High [email protected] Content Standards 11.2.2: Describe the changing landscape, including the growth of cities linked by industry and trade, and the development of cities divided according to race, ethnicity and class. CCSS Standards CCSS.ELA-READING FOR LITERACY IN HISTORY.RH.11-12.9: Integrate information from diverse sources, both primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources. CCSS.ELA-READING FOR LITERACY IN HISTORY.RH.11-12.2: Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas. CCSS.ELA-READING FOR LITERACY IN HISTORY.RH.11-12.3: Evaluate various explanations for actions or events and determine which explanation best accords with textual evidence, acknowledging where the text leaves matters uncertain. CCSS. ELA-WRITING FOR LITERACY IN HISTORY. WHST.11-12.1a.b.e: Introduce precise, knowledgeable claim(s), establish the significance of the claim(s), distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and create an organization that logically sequences the claim(s), counterclaims, reasons, and evidence. Develop claim(s) and counterclaims fairly and thoroughly, supplying the most relevant data and evidence for each while pointing out the strengths and limitations of both claim(s) and counterclaims in a discipline-appropriate form that anticipates the audience’s knowledge level, concerns, values, and possible biases. -

Medical School Expansion in the 21St Century Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine

Medical School Expansion in the 21st Century Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine Michael E. Whitcomb, M.D. and Douglas L. Wood, D.O., Ph.D. September 2015 Cover: University of New England campus Medical School Expansion in the 21st Century Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine Michael E. Whitcomb, M.D. and Douglas L. Wood, D.O., Ph.D. FOREWORD The Macy Foundation has recently documented the motivating factors, major challenges, and planning strategies for the fifteen new allopathic medical schools (leading to the M.D. degree) that enrolled their charter classes between 2009 and 2014.1,2 A parallel trend in the opening of new osteopathic medical schools (leading to the D.O. degree) began in 2003. This expansion will result in a greater proportional increase in the D.O. workforce than will occur in the M.D. workforce as a result of the allopathic expansion. With eleven new osteopathic schools and nine new sites or branches for existing osteopathic schools, there will be more than a doubling of the D.O. graduates in the U.S. by the end of this decade. Douglas Wood, D.O., Ph.D., and Michael Whitcomb, M.D., bring their broad experiences in D.O. and M.D. education to this report of the osteopathic school expansion. They identify ways in which the new schools are similar to and different from the existing osteopathic schools, and they identify differences in the rationale and characteristics of the new osteopathic schools, compared with those of the new allopathic schools that Dr. Whitcomb has previously chronicled. 1 Whitcomb ME. -

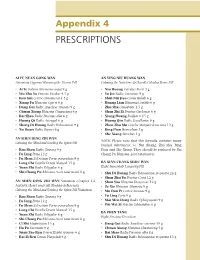

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS AI FU NUAN GONG WAN AN YING NIU HUANG WAN Artemisia-Cyperus Warming the Uterus Pill Calming the Nutritive-Qi [Level] Calculus Bovis Pill • Ai Ye Folium Artemisiae argyi 9 g • Niu Huang Calculus Bovis 3 g • Wu Zhu Yu Fructus Evodiae 4.5 g • Yu Jin Radix Curcumae 9 g • Rou Gui Cortex Cinnamomi 4.5 g • Shui Niu Jiao Cornu Bubali 6 g • Xiang Fu Rhizoma Cyperi 9 g • Huang Lian Rhizoma Coptidis 6 g • Dang Gui Radix Angelicae sinensis 9 g • Zhu Sha Cinnabaris 1.5 g • Chuan Xiong Rhizoma Chuanxiong 6 g • Shan Zhi Zi Fructus Gardeniae 6 g • Bai Shao Radix Paeoniae alba 6 g • Xiong Huang Realgar 0.15 g • Huang Qi Radix Astragali 6 g • Huang Qin Radix Scutellariae 9 g • Sheng Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae 9 g • Zhen Zhu Mu Concha Margatiriferae usta 12 g • Xu Duan Radix Dipsaci 6 g • Bing Pian Borneolum 3 g • She Xiang Moschus 1 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN NOTE: Please note that this formula contains many Calming the Mind and Settling the Spirit Pill banned substances, i.e. Niu Huang, Zhu Sha, Bing • Ren Shen Radix Ginseng 9 g Pian and She Xiang. They should be replaced by Shi • Fu Ling Poria 12 g Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii. • Fu Shen Sclerotium Poriae pararadicis 9 g • Long Chi Fossilia Dentis Mastodi 15 g BA XIAN CHANG SHOU WAN • Yuan Zhi Radix Polygalae 6 g Eight Immortals Longevity Pill • Shi Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii 8 g • Shu Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae preparata 24 g • Shan Zhu Yu Fructus Corni 12 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN Variation (Chapter 14, • Shan Yao Rhizoma Dioscoreae 12 g Anxiety, Heart and Gall Bladder -

340336 1 En Bookbackmatter 251..302

A List of Historical Texts 《安禄山事迹》 《楚辭 Á 招魂》 《楚辭注》 《打馬》 《打馬格》 《打馬錄》 《打馬圖經》 《打馬圖示》 《打馬圖序》 《大錢圖錄》 《道教援神契》 《冬月洛城北謁玄元皇帝廟》 《風俗通義 Á 正失》 《佛说七千佛神符經》 《宮詞》 《古博經》 《古今圖書集成》 《古泉匯》 《古事記》 《韓非子 Á 外儲說左上》 《韓非子》 《漢書 Á 武帝記》 《漢書 Á 遊俠傳》 《和漢古今泉貨鑒》 《後漢書 Á 許升婁傳》 《黃帝金匱》 《黃神越章》 《江南曲》 《金鑾密记》 《經國集》 《舊唐書 Á 玄宗本紀》 《舊唐書 Á 職官志 Á 三平准令條》 《開元別記》 © Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2016 251 A.C. Fang and F. Thierry (eds.), The Language and Iconography of Chinese Charms, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-1793-3 252 A List of Historical Texts 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷二 Á 戲擲金錢》 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷三》 《雷霆咒》 《類編長安志》 《歷代錢譜》 《歷代泉譜》 《歷代神仙通鑑》 《聊斋志異》 《遼史 Á 兵衛志》 《六甲祕祝》 《六甲通靈符》 《六甲陰陽符》 《論語 Á 陽貨》 《曲江對雨》 《全唐詩 Á 卷八七五 Á 司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《泉志 Á 卷十五 Á 厭勝品》 《勸學詩》 《群書類叢》 《日本書紀》 《三教論衡》 《尚書》 《尚書考靈曜》 《神清咒》 《詩經》 《十二真君傳》 《史記 Á 宋微子世家 Á 第八》 《史記 Á 吳王濞列傳》 《事物绀珠》 《漱玉集》 《說苑 Á 正諫篇》 《司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《私教類聚》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十一 Á 志第一百四 Á 輿服三 Á 天子之服 皇太子附 后妃之 服 命婦附》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十二 Á 志第一百五 Á 輿服四 Á 諸臣服上》 《搜神記》 《太平洞極經》 《太平廣記》 《太平御覽》 《太上感應篇》 《太上咒》 《唐會要 Á 卷八十三 Á 嫁娶 Á 建中元年十一月十六日條》 《唐兩京城坊考 Á 卷三》 《唐六典 Á 卷二十 Á 左藏令務》 《天曹地府祭》 A List of Historical Texts 253 《天罡咒》 《通志》 《圖畫見聞志》 《退宮人》 《萬葉集》 《倭名类聚抄》 《五代會要 Á 卷二十九》 《五行大義》 《西京雜記 Á 卷下 Á 陸博術》 《仙人篇》 《新唐書 Á 食貨志》 《新撰陰陽書》 《續錢譜》 《續日本記》 《續資治通鑑》 《延喜式》 《顏氏家訓 Á 雜藝》 《鹽鐵論 Á 授時》 《易經 Á 泰》 《弈旨》 《玉芝堂談薈》 《元史 Á 卷七十八 Á 志第二十八 Á 輿服一 儀衛附》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 符圖部》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 三洞經教部》 《韻府帬玉》 《戰國策 Á 齊策》 《直齋書錄解題》 《周易》 《莊子 Á 天地》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二百一十六 Á 唐紀三十二 Á 玄宗八載》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二一六 Á 唐天寶十載》 A Chronology of Chinese Dynasties and Periods ca. -

Mr. Bai and Mr. Qian Earntheir Living: Considering Two Handwritten Notebooks of Matching Couplets from China in the Late Qing An

chapter 7 Mr. Bai and Mr. Qian Earn Their Living: Considering Two Handwritten Notebooks of Matching Couplets from China in the Late Qing and Early Republic 老白老錢寫對聯兒 Introduction This chapter explores two chaoben that I bought in China in the spring of 2012. They were written between the end of the Qing dynasty, around 1880, and the early years of the Republic, about 1913. They were both written by literate men whose daily life was very close to the common people in terms of their life expectations and their modest incomes. The men, who had received some formal education and had the ability to read and to write, took advantage of those abilities to earn income by preparing couplets of congratulatory poems that were, and still are, a big part of the social and celebratory life of the Chinese. By attempting to draw inferences and make logical assumptions from the information in these two chaoben and the manner in which the information was presented, I suggest the ways in which they can reveal something about the lives, the worldview, and the economic standing of both men. By looking carefully at the contents of what they wrote, we see that these chaoben can also be used to reconstruct something about the communities in which both men lived and worked. The bulk of the content in both chaoben is matching couplets. Many literate men in this period could regularly earn extra income by offering to write matching couplets, celebratory rhyming phrases that were demanded on many social occasions, such as New Year festivities and weddings.