Feasibility of Champlain Canal Aquatic Nuisance Species Barrier Options

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Champlain Canalway Trail 2018 Action Plan

Champlain Canalway Trail 2018 Action Plan Presentation To Washington County Adhoc Trails Committee Meeting January 16, 2019 The Setting Saratoga & Washington Counties 19 Municipalities 3 Rivers: Mohawk River; Hudson River; Batten Kill 3 Canals: Champlain Barge Canal Old Champlain Canal Glens Falls Feeder Canal 2 The Partners ▪ Champlain Canalway Trail Working Group ▪ Assisted by a Hudson River Valley Greenway Grant ▪ Administered through the Town of Stillwater ▪ Washington County & Saratoga County Planning Departments ▪ Empire State Trail ▪ Hudson River Valley Greenway, Saratoga and Washington Counties and the private sector will complete 3 Regional Context The CCT received a boost from Governor Cuomo’s Empire State Trail initiative to create a continuous 750-mile route spanning the state from New York City to Canada and Buffalo to Albany, creating the longest multi-use state trail in the nation. 4 Regional Context 5 The 2020 CCT Trail Vision ▪ Establish a continuous 77-mile multi- use trail from Waterford to Whitehall along the Hudson River and Champlain Canal. ▪ Utilize the historic Champlain Canalway Towpath, Champlain Canal shoreline, existing local and regional trails, and on-street bicycle routes. ▪ Link the region’s historic, cultural, natural and recreational assets into a system of interconnected canal lock parks, visitor centers, downtowns. ▪ Coordinate marketing with Empire State Trail. ▪ Establish a world-class destination for residents and visitors. 6 Accomplishments and Gaps 77.65 TOTAL MILES OF LINEAR TRAIL (INCLUDING THE -

Erie Canalway Map & Guide

National Park Service Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor U.S. Department of the Interior Erie Canalway Map & Guide Pittsford, Frank Forte Pittsford, The New York State Canal System—which includes the Erie, Champlain, Cayuga-Seneca, and Oswego Canals—is the centerpiece of the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor. Experience the enduring legacy of this National Historic Landmark by boat, bike, car, or on foot. Discover New York’s Dubbed the “Mother of Cities” the canal fueled the growth of industries, opened the nation to settlement, and made New York the Empire State. (Clinton Square, Syracuse, 1905, courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Extraordinary Canals Company Collection.) pened in 1825, New York’s canals are a waterway link from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes through the heart of upstate New York. Through wars and peacetime, prosperity and This guide presents exciting Orecession, flood and drought, this exceptional waterway has provided a living connection things to do, places to go, to a proud past and a vibrant future. Built with leadership, ingenuity, determination, and hard work, and exceptional activities to the canals continue to remind us of the qualities that make our state and nation great. They offer us enjoy. Welcome! inspiration to weather storms and time-tested knowledge that we will prevail. Come to New York’s canals this year. Touch the building stones CONTENTS laid by immigrants and farmers 200 years ago. See century-old locks, lift Canals and COVID-19 bridges, and movable dams constructed during the canal’s 20th century Enjoy Boats and Boating Please refer to current guidelines and enlargement and still in use today. -

Progress of Stream Measurements

Water-Supply and Irrigation Paper No. 166 Series P, Hydrographic Progress Reports, 42 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIKECTOK REPORT PROGRESS OF STREAM MEASUREMENTS FOR THE CALENDAR YEAR 1905 PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF F. H. NEWELL PART II. Hudson, Passaic, Raritan, and Delaware River Drainages BY R. E. HORTON, N. C. GROVER, and JOHN C. HOYT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1906 Water-Supply and Irrigation Paper No. 166 Series P, HydwgrapMe Progress Reporte, 42 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DlKECTOK REPORT PROGRESS OF STREAM MEASUREMENTS THE CALENDAR YEAR 1905 PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF F. H. NEWELL PART II. Hudson, Passaic, Raritan, and Delaware River Drainages » BY R. E. HORTON, N. C. GROVER, and JOHN C. HOYT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1906 CONTENTS. Page. Introduction......-...-...................___......_.....-.---...-----.-.-- 5 Organization and scope of work.........____...__...-...--....----------- 5 Definitions............................................................ 7 Explanation of tables...............................-..--...------.----- 8 Convenient equivalents.....-......._....____...'.--------.----.--------- 9 Field methods of measuring stream flow................................... 10 Office methods of computing run-off...................................... 14 Cooperation and acknowledgments................--..-...--..-.-....-..- 16 Hudson River drainage basin............................................... -

New York Freshwater Fishing Regulations Guide: 2015-16

NEW YORK Freshwater FISHING2015–16 OFFICIAL REGULATIONS GUIDE VOLUME 7, ISSUE NO. 1, APRIL 2015 Fishing for Muskie www.dec.ny.gov Most regulations are in effect April 1, 2015 through March 31, 2016 MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNOR New York: A State of Angling Opportunity When it comes to freshwater fishing, no state in the nation can compare to New York. Our Great Lakes consistently deliver outstanding fishing for salmon and steelhead and it doesn’t stop there. In fact, New York is home to four of the Bassmaster’s top 50 bass lakes, drawing anglers from around the globe to come and experience great smallmouth and largemouth bass fishing. The crystal clear lakes and streams of the Adirondack and Catskill parks make New York home to the very best fly fishing east of the Rockies. Add abundant walleye, panfish, trout and trophy muskellunge and northern pike to the mix, and New York is clearly a state of angling opportunity. Fishing is a wonderful way to reconnect with the outdoors. Here in New York, we are working hard to make the sport more accessible and affordable to all. Over the past five years, we have invested more than $6 million, renovating existing boat launches and developing new ones across the state. This is in addition to the 50 new projects begun in 2014 that will make it easier for all outdoors enthusiasts to access the woods and waters of New York. Our 12 DEC fish hatcheries produce 900,000 pounds of fish each year to increase fish populations and expand and improve angling opportunities. -

Progress of Stream Measurements

Water-Supply and Irrigation Paper No. 125 Series P, Hydrographic Progress Reports, 30 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR REPORT PROGRESS OF STREAM MEASUREMENTS THE CALENDAR YEAR 1904 PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF F. H. NEWELL BY R. E. HORTON, N. C. GROVER, and JOHN C. HOYT PART II. Hudson, Passaic, Raritan, and Delaware River Drainages WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1905 Water-Supply and Irrigation Paper No. 125 Series P, Hydrographic Progress Reports, 30 i DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR REPORT PROGRESS OF STREAM MEASUREMENTS THE CALENDAR YEAR 1904 PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF F. H. NEWELL BY R. E. HORTON, N. C. GROVER, and JOHN C. HOYT PART II. Hudson, Passaic, Raritan, and Delaware River Drainages WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1905 CONTENTS. Letter of transmittal...................................................... 7 Introduction............................................................. 9 Cooperation and acknowledgments ...... ...^.............................. 18 Hudson Eiver drainage basin. ............................................ 19 Hudson Eiver at Fort Edward, N. Y .............................. 19 Hudson Eiver at Mechanicsville, N. Y............................. 22 Indian Eiver at Indian Lake, Hamilton County, N. Y.............. 24 Hoosic Eiver at Buskirk, N. Y .................................... 24 Mohawk River at Little Falls, N. Y................................ 26 Mohawk Eiver at Dunsbach Ferry Bridge, N. Y.................... 29 Oriskany Creek near Oriskany, N. Y .............................. 32 Starch Factory Creek near New Hartford, N. Y.................... 35 Sylvan Glen Creek near New Hartford, N. Y....................... 37 Graefenberg Creek near New Hartford, N. Y....................... 39 Eeels Creek and Johnston Brook near Deer-field, N. Y.............. 41 Nail Creek at Utica, N. Y......................................... 45 West Canada Creek at Twin Eock Bridge, N. Y................... -

Great Lakes Deliveries and Cruising

Great Lakes Deliveries and Cruising Captains Roy Adler & Ken Hawes OUTLINE •Background •Cruise Planning •Great Lakes Pathways •Special Items •Route Selection •Q & A •Delivery Planning Atlantic Access Approximately 250 statute Miles to St. Lawrence Seaway Champlain Canal Lake Champlain Richelieu River Chambly Canal Great Lake Distances (in statute miles) Great Lake Length Width Lake Ontario 192 53 Lake Erie 240 38 - 57 Lake Huron 206 183* Lake Michigan 307 118 Lake Superior 350 160 *widest point HUDSON RIVERText ACCESS statute height Canal locks days miles restrictions Erie 363 57 15.5’ 5 Erie - 204 30 21’ 3 Oswego Champlain 64 12 15.5’-17’ 1 Chambly 12 9 29’ <1 Welland 27 8 N/A <1 to 2 Trent - 239 44 22’ 5 Severn ATLANTIC OCEAN ACCESS height Waterway statute miles locks restrictions Canso Strait 17 1 N/A St. Lawrence 2500 15 N/A Seaway* * Gulf of St.Lawrence to Lake Erie ANNAPOLIS TO CHICAGO Routes Approximate Statute Miles Erie Canal 1700 Erie -Oswego - Welland Canals 1700 Erie-Oswego-Trent-Severn 1600 Canals Champlain - Chambly - St. 2200 Lawrence -Welland Canals Champlain - Chambly - St. 2100 Lawrence -Trent-Severn Canso Strait - Welland 3900 Canso Strait - Trent-Severn 3800 ROUTE SELECTION Yacht Height Owners Requirements Weather Forecast Fuel Range Lock Crew Requirements Yacht Length and Weight CHICAGO DELIVERY PLANNING 52’ Carver Voyager’ Fuel Tank -- 800 gallons Cruise Burn Rate -- 50 gal./hour Cruise speed -- 25 knots Distance -- 1700 miles Boat Height -- 20’ *Plan Days -- 9 * assumes perfect weather ERIE CANAL ENT ERIE CANAL TOLL BUILDING ERIE CANAL TYPICAL LOCK ERIE CANAL Fender Arrangement ERIE CANAL REMOTE SECTION ERIE CANAL SCHENECTADY YACHT CLUB ERIE CANAL OLD BARGE ERIE CANAL ILION MARINA ERIE CANAL TYPICAL LINE WITH WEIGHTS LAKE ONEIDA BRIDGE ON WESTERN SIDE OSWEGO CANAL MOVING INTO OSWEGO, NY OSWEGO MARINA LAKE ONTARIO LAKE ONTARIO LEAVING OSWEGO, NY ST. -

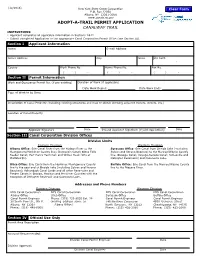

ADOPT-A-TRAIL PERMIT APPLICATION CANALWAY TRAIL INSTRUCTIONS: • Applicant Completes All Applicable Information in Sections I & II

(12/2016) New York State Canal Corporation P.O. Box 22058 Albany, NY 12201-2058 www.canals.ny.gov ADOPT-A-TRAIL PERMIT APPLICATION CANALWAY TRAIL INSTRUCTIONS: • Applicant completes all applicable information in Sections I & II. • Submit completed Application to the appropriate Canal Corporation Permit Office (see Section III). Section I Applicant Information Name E-mail Address Street Address City State Zip Code - County Work Phone No. Home Phone No. Fax No. ( ) - ( ) - ( ) - Section II Permit Information Work and Occupancy Permit No. (if pre-existing) Duration of Work (if applicable) Date Work Begins: Date Work Ends: Type of Work to be Done Description of Canal Property (including existing structures and map or sketch showing adjacent owners, streets, etc.) Location of Canal Property Applicant Signature Date Second Applicant Signature (if joint application) Date Section III Canal Corporation Division Offices Division Limits Eastern Division Western Division Albany Office: Erie Canal River from the Hudson River to the Syracuse Office: Erie Canal from Oneida Lake (excluding Montgomery/Herkimer County line; Champlain Canal; Glens Falls Sylvan and Verona Beaches) to the Monroe/Wayne County Feeder Canal; Port Henry Terminal; and Wilcox Dock (City of line; Oswego Canal; Cayuga-Seneca Canal; Jamesville and Plattsburgh). DeRuyter Reservoirs; and Cazenovia Lake. Utica Office: Erie Canal from the Herkimer/Montgomery County Buffalo Office: Erie Canal from the Monroe/Wayne County line to the east end of Oneida Lake (including Sylvan and Verona line to the Niagara River. Beaches); Adirondack Canal Lands and all other Reservoirs and Feeder Canals in Oneida, Madison and Herkimer Counties with the exception of DeRuyter Reservoir and Cazenovia Lake. -

Barge Canal” Is No Longer an Accurate Description of the New York State Canals Marine Activity on New York’S Canals

The Story of the Afterword Today, the name “Barge Canal” is no longer an accurate description of the New York State Canals marine activity on New York’s canals. Trains and trucks have taken over the transport of most cargo that once moved on barges along the canals, but the canals remain a viable waterway for navigation. Now, pleasure boats, tour Historical and Commercial Information boats, cruise ships, canoes and kayaks comprise the majority of vessels that ply the waters of the legendary Erie and the Champlain, Oswego and Cayuga- Seneca canals, which now constitute the 524-mile New York State Canal ROY G. FINCH System. State Engineer and Surveyor While the barges now are few, this network of inland waterways is a popular tourism destination each year for thousands of pleasure boaters as well as visitors by land, who follow the historic trade route that made New York the “Empire State.” Across the canal corridor, dozens of historic sites, museums and community festivals in charming port towns and bustling cities invite visitors to step back in time and re-live the early canal days when “hoggees” guided mule-drawn packet boats along the narrow towpaths. Today, many of the towpaths have been transformed into Canalway Trail segments, extending over 220 miles for the enjoyment of outdoor enthusiasts from near and far who walk, bike and hike through scenic and historic canal areas. In 1992, legislation was enacted in New York State which changed the name of the Barge Canal to the “New York State Canal System” and transferred responsibility for operation and maintenance of the Canal System from the New York State Department of Transportation to the New York State Canal Corporation, a newly created subsidiary of the New York State Thruway Authority. -

Downtown and Waterfront Revitalization Plan I V

Downtown & Waterfront Revitalization Plan for the Village of Rouses Point Prepared for: Village of Rouses Point Clinton County, New York Submittal Date: June 22, 2006 Prepared by: This document was prepared for the Village of Rouses Point with funds provided by the New York State Department of State Division of Coastal Resources under Title 11 of the Environmental Protection Fund Act. I. PROJECT OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................1 II. DOWNTOWN AND WATERFRONT VISION.............................................................5 A. THE FUTURE OF DOWNTOWN ROUSES POINT........................................................ 5 B. THE PUBLIC VISION PROCESS..................................................................................... 6 C. VISION FOR DOWNTOWN ROUSES POINT................................................................ 8 D. COMMON THEMES/GUIDING PRINCIPLES............................................................... 8 III. DOWNTOWN AND WATERFRONT PROFILE .........................................................9 A. VILLAGE SETTING.......................................................................................................... 9 B. STUDY AREA PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT .................................................................. 10 C. EXISTING MARKET CONDITIONS............................................................................. 13 1. Retail Trade Area......................................................................................................... -

Minutes of the Regular Joint Meeting of the Power Authority of the State of New York and New York State Canal Corporation

MINUTES OF THE REGULAR JOINT MEETING OF THE POWER AUTHORITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK AND NEW YORK STATE CANAL CORPORATION May 21, 2019 Table of Contents Subject Page No. Exhibit Introduction 2 1. Adoption of the May 21, 2019 Proposed Meeting Agenda 3 2. Motion to Conduct an Executive Session 4 3. Motion to Resume Meeting in Open Session 5 4. CONSENT AGENDA: 6 a. Governance Matters 7 i. Minutes of the Annual Joint Meeting of the 7 New York Power Authority’s Trustees and Canal Corporation’s Board of Directors held on March 26, 2019 b. Power Allocations 8 i. Transfer of Recharge New York Power, 8 Expansion Power and Replacement Power Allocations – TABLED ii. Replacement Power Allocation 9 4b ii-A iii. Recharge New York Power - Allocation 11 Extensions – TABLED iv. Recommendation for Award of Fund Benefits 12 4b iv-A from the Western New York Economic 4b iv-A-1 Development Fund Recommended by the 4b iv-B Western New York Power Proceeds Allocation Board c. Procurement (Services) Contracts 16 i. Procurement (Services) and Other Contracts – 16 4c i-A Business Units and Facilities – Awards, 4c i-B Extensions and/or Additional Funding May 21, 2019 Subject Page No. Exhibit ii. St. Lawrence-FDR Power Project – Facilities 23 for Office of Parks – Capital Expenditure Authorization Request and Contract Award iii. Extension of the Gas Transportation 26 4c iii-A and Balancing Service Agreement with Consolidated Edison Company of New York Inc. iv. Seaway Private Equity Corporation – Grant 29 4c iv-A Agreement Amendment d. Finance 31 i. -

Cohoes-Waterford Concept Plan.Pub

Cohoes—Waterford Canalway Trail Connection Study Prepared for New York State Canal Corporation By Parks and Trails New York Final Draft Version Cohoes-Waterford Canalway Trail Connection Study Final Draft Version September 2004 Page 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 2 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 3 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 Existing trail initiatives in the study area ...................................................................... 6 Purpose of Study .......................................................................................................... 7 Inventory and Analysis of Study Area ................................................................................. 7 Canalway Trail Resources ........................................................................................... 7 Waterford Canal Harbor Visitor Center ........................................................................9 Hudson Valley Greenway Trail ...................................................................................10 Street System Resources ................................................................................................. 11 Streets ....................................................................................................................... -

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13Th) Edition

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13th) Edition T OF EN CO M M T M R E A R P C E E D U N A I C T I E R D E S M T A ATES OF U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) RDML Timothy Gallaudet., Ph.D., USN Ret., Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and Acting Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere National Ocean Service Nicole R. LeBoeuf, Deputy Assistant Administrator for Ocean Services and Coastal Zone Management Cover image courtesy of Megan Greenaway—Great Salt Pond, Block Island, RI III Preface Distances Between United States Ports is published by the Office of Coast Survey, National Ocean Service (NOS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), pursuant to the Act of 6 August 1947 (33 U.S.C. 883a and b), and the Act of 22 October 1968 (44 U.S.C. 1310). Distances Between United States Ports contains distances from a port of the United States to other ports in the United States, and from a port in the Great Lakes in the United States to Canadian ports in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. Distances Between Ports, Publication 151, is published by National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and distributed by NOS. NGA Pub. 151 is international in scope and lists distances from foreign port to foreign port and from foreign port to major U.S. ports. The two publications, Distances Between United States Ports and Distances Between Ports, complement each other.