MHI-06 Evolution of Social Structures in India Through the Ages 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIT 1 UNITY and DIVERSITY Unity and Diversity

UNIT 1 UNITY AND DIVERSITY Unity and Diversity Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Concepts of Unity and Diversity 1.2.1 Meaning of Diversity 1.2.2 Meaning of Unity 1.3 Forms of Diversity in India 1.3.1 Racial Diversity 1.3.2 Linguistic Diversity 1.3.3 Religious Diversity 1.3.4 Caste Diversity 1.4 Bonds of Unity in India 1.4.1 Geo-political Unity 1.4.2 The Institution of Pilgrimage 1.4.3 Tradition of Accommodation 1.4.4 Tradition of Interdependence 1.5 Let Us Sum Up 1.6 Keywords 1.7 Further Reading 1.8 Specimen Answers to Check Your Progress 1.0 OBJECTIVES After studying this unit you should be able to z explain the concept of unity and diversity z describe the forms and bases of diversity in India z examine the bonds and mechanisms of unity in India z provide an explanation to our option for a composite culture model rather than a uniformity model of unity. 1.1 INTRODUCTION This unit deals with unity and diversity in India. You may have heard a lot about unity and diversity in India. But do you know what exactly it means? Here we will explain to you the meaning and content of this phrase. For this purpose the unit has been divided into three sections. In the first section, we will specify the meaning of the two terms, diversity and unity. 9 Social Structure Rural In the second section, we will illustrate the forms of diversity in Indian society. -

The Shaping of Modern Gujarat

A probing took beyond Hindutva to get to the heart of Gujarat THE SHAPING OF MODERN Many aspects of mortem Gujarati society and polity appear pulling. A society which for centuries absorbed diverse people today appears insular and patochiai, and while it is one of the most prosperous slates in India, a fifth of its population lives below the poverty line. J Drawing on academic and scholarly sources, autobiographies, G U ARAT letters, literature and folksongs, Achyut Yagnik and Such Lira Strath attempt to Understand and explain these paradoxes, t hey trace the 2 a 6 :E e o n d i n a U t V a n y history of Gujarat from the time of the Indus Valley civilization, when Gujarati society came to be a synthesis of diverse peoples and cultures, to the state's encounters with the Turks, Marathas and the Portuguese t which sowed the seeds ol communal disharmony. Taking a closer look at the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the authors explore the political tensions, social dynamics and economic forces thal contributed to making the state what it is today, the impact of the British policies; the process of industrialization and urbanization^ and the rise of the middle class; the emergence of the idea of '5wadeshi“; the coming £ G and hr and his attempts to transform society and politics by bringing together diverse Gujarati cultural sources; and the series of communal riots that rocked Gujarat even as the state was consumed by nationalist fervour. With Independence and statehood, the government encouraged a new model of development, which marginalized Dai its, Adivasis and minorities even further. -

Dadra & Nagar Haveli Town Survey Report Sil Vassa, Part X-B, Series-27

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 PART-XB SERlES-27 DADRA & NAGAR HAVELI TOWN SURVEY REPORT SILVASSA s. RAJENDRAN Deputy Director of Census Operatio1U Datlra &: Nagar Havill; , A R .111 0 I , , IOIIIIIot.ftY, STAIr . ..•,_il_,' .. VILLAGE/URIAN Am .. ~. ____ /_ ~.oGIJA1'EI!S· DISTRICT I TAlllKA .. 110 _I.NT METALlfD ROAO ,,,. III'U .ND 5TI£AM _ .......... '" ~ t. tJlUlI \ 5 a.uIO U'IIII SlJAvn OF INOlA MAP ~I"~ !WE PERMISSION 0' lfIvnOA GEICUt OP .... @6QvtUII£Nl Of INDI~ ~"Hl,.I"I. I buring tho f'reodom movomon~ tho local nationalist workers used to pther and shout slogans (or fraodom with tho national Bags in thoir hands at this place. Immodiatoly aftor tho liboration of Dadra & Nagar Havc1i, tho nationalists un furled tho National Flag at this place to mark tho liberation from tho colonial rulo ot tho Portuguoao. Asmall monumont has boon orocted in this chowk in memory of _ who laid don ahoit tiv. ia tho ItruulO tor tr.Jom. - 1981 CENSUS PUBLIOATIONS OF DADRA & NAGAR HAVELI (All the Census Publications of this Union Territory will bear series No. 27) CeatraI Govenuoeat PubUcatI_ PtI1't I-A Administration Report-Enumeration (for official \ISO only) I-B Administration Report-Tabulation (for official usc only) ll-A & ll-B General Population Tables and Primary Census Abstract m-A & B Goneral Economic Tables and Social and Cultural Tables. & IV-A Y-A&B Migration Tabl. VI-A&B Fertility Tablos VII Tables and Ho\lS08 & Disablad Population. Vm-A&B Housohold Tablos IX Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes XB Survey Reports on selected towns XC Survey Reports on selected villages XU Census Atlas Publications of the Administratioll of Dado & Nagar Hayeli Xlll-A~B Villa.$c and Town Directory and Village and Town-wise Primary Omsus Abstract, (I) 1-338 It. -

(PIL) NO. 108 of 2016 with SPECIAL CIVIL APPLICATION NO. 8804 of 2016 with SPECIAL CIVIL APPLICATION NO

C/WPPIL/108/2016 CAV JUDGMENT IN THE HIGH COURT OF GUJARAT AT AHMEDABAD WRIT PETITION (PIL) NO. 108 of 2016 With SPECIAL CIVIL APPLICATION NO. 8804 of 2016 With SPECIAL CIVIL APPLICATION NO. 8655 of 2016 With SPECIAL CIVIL APPLICATION NO. 9740 of 2016 FOR APPROVAL AND SIGNATURE: HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE MR. R.SUBHASH REDDY and HONOURABLE MR.JUSTICE VIPUL M. PANCHOLI ========================================================== 1 Whether Reporters of Local Papers may be allowed to see the judgment ? 2 To be referred to the Reporter or not ? 3 Whether their Lordships wish to see the fair copy of the judgment ? 4 Whether this case involves a substantial question of law as to the interpretation of the Constitution of India or any order made thereunder ? ========================================================== DAYARAM KHEMKARAN VERMA S/O KHEMKARAN VERMA....Applicants Versus STATE OF GUJARAT & 1....Opponents ========================================================== Appearance: WP(PIL) NO 108 OF 2016: MR IH SYED with MR RAHUL SHARMA, ADVOCATE for Petitioner MR KAMAL B TRIVEDI, ADVOCATE GENERAL with MS SK VISHEN, AGP Page 1 of 104 HC-NIC Page 1 of 104 Created On Fri Aug 05 16:38:32 IST 2016 C/WPPIL/108/2016 CAV JUDGMENT with MR PK JANI, ADDITIONAL ADVOCATE GENERAL with MS ML SHAH, GOVERNMENT PLEADER for Respondent No. 1 MR AMIT PANCHAL with MS SHIVANI RAJPUROHIT, ADVOCATE for Respondent No. 2 SPECIAL CIVIL APPLICATION NO 8804 OF 2016: MR SN SHELAT, SR. ADVOCATE with MS VD NANAVATI,ADVOCATE for Petitioners MR KAMAL B TRIVEDI, ADVOCATE GENERAL with MS SK VISHEN, AGP with MR PK JANI, ADDITIONAL ADVOCATE GENERAL with MS ML SHAH, GOVERNMENT PLEADER for Respondent No. -

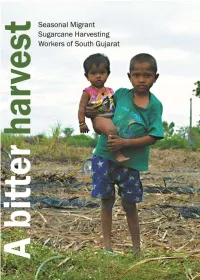

Studies Surat for Providing Critical Inputs in Design and Writing of the Study and Hosting Two Consultations Related to the Study

Acknowledgements The report was researched and published by Prayas Centre for Labor Research and Action (PCLRA). It was sponsored by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation e.v. with funds of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development of the Federal Republic of Germany. We thank Centre for Social Studies Surat for providing critical inputs in design and writing of the study and hosting two consultations related to the study. PCLRA would like to thank the workers who participated in the study. Research team Prof. Kiran Desai Sudhir Katiyar Video and photography Denis Macwan Data collection Shanti Lal Meena Denis Macwan Amar Nath Sanjay Dayal Thakor Balwant Singh Dinesh Parmar Editing Dhruv Sharma Design Pollencomm Printed at .................... A Bitter Harvest Seasonal Migrant Sugarcane Harvesting Workers of South Gujarat Findings of a Research Study December 2017 Study undertaken by Prayas through its designated unit Centre for Labour Research and Action Sponsored by Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung PrayasCentre for Labour Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Research and Action (PCLRA) FORWARD Sugarcane is the money spinning crop which has much added to the wealth of the main landowners in south Gujarat. The cutting of this crop is known as ‘the campaign’ and lasts for four to five months in between November and May. A huge labour army is annually recruited already for more than half a century by the management of mills set up and owned by co-operatives to harvest the cane which is cultivated in the fields of the farmers who are members and owners of these enterprises. “The crushing of cane and of labour” was how I wrote up my findings of the anthropological fieldwork in and around Bardoli. -

Caste and Class in India

Caste And Class In India G. S. GHURYE Professor and Head of the Dept. of Sociology, University of Bombay 1957 BOOK DEPOT BOMBAY First published as Caste and Race in India in 1932 Caste and Class in India First Published 1950 Second Edition 1957 Printed by G.. G.Pathare, at the Popular Press (Bom.) Private Ltd., :29, Tardeo Road, Bombay 7, and published by G. R. Bhatkal fer the Popular Book Depot, Lamington Road, Bombay 7 CONTENTS Page Preface vii Preface to the 1st Edition ix Preface to Caste and Race in India xiii CHAPTER 1 Features of" the Caste System 1 CHAPTER 2 Nature of Caste Groups 31 CHAPTER 3 Caste through the Ages 4~ CHAPTER 4 Caste through the Ages (II) 76 CHAPTER 5 Race and Caste 116 CHAPTER 6 Elements of Caste outside India 143 CHAPTER 7 Origins of Caste System 165 CHAPTER 8 Caste and British Rule 184 CHAPTER 9 Caste and Nationalism 220 CHAPTER 10 Scheduled Castes .. 240 CHAPTER 11 Class and Its Role.. 268 Appendices A to G 290 Bibliographical Abbreviations 297 Index 303 PREFACE In this edition of my book I have reinstated the chapter on Race which I had dropped out from the last edition. Teachers of the subject represented to me that the deletion of that chapter was felt by them and their students to be a great handicap in the study of caste. I have therefore brought it up-to-date and included it in this edition. In keeping with the new political and social set-up-I must point out that at the time of the last edition, the Constitution of India was not framed or published-I have added a much-needed chapter on Scheduled Castes. -

Chapter: I Research Methodology and Planning

CHAPTER: I RESEARCH METHODOLOGY AND PLANNING OF THE RESEARCH Sr. No. Details Page No. 1.1 Introduction 6-14 1.2 Beginning 14-15 1.3 Form 15 1.4 Form of Research 15 - 16 1.5 Fundamental Base of Research 16 - 18 1.6 Selection of Subject for Research 18 - 24 1.7 Problems of Research 24 1.8 Formation of the Area of Research 24 - 25 1.9 Thoughts of Research 25 - 41 1.10 Field Work in the Area under Study 41-42 1.11 Selection of Research Units 42 1.12 Research Methods of Field Work (Study Destinies, Research 42-49 Methods Used for Research) 1.13 Research Method 49-53 1.14 Data Collection 53-54 1.15 Review of Available Literature 54-68 1.16 Research Hypothesis 68-70 1.17 Importance of Research 71 1.18 Objectives of Research 71-74 1.19 Analysis and Interpretation of Data 74 1.20 Tabulation 74-75 1.21 Main Aspects of the Research (Constitution of the Report of 75-76 Research) 1.22 Limitations of the Study 76-77 1.23 Experiences of Field Work 77-78 1.24 Conclusion 78-79 References 80-82 1 CHAPTER: I RESEARCH METHODOLOGY AND PLANNING OF THE RESEARCH Sr. No. Details Page No. 1.1 Introduction 6-14 1.2 Beginning 14-15 1.3 Form 15 1.4 Form of Research 15-16 1.4.1 Pure Research 16 1.4.2 Applied Research 16 1.5 Fundamental Base of Research 16-18 1.6 Selection of Subject for Research 18-23 1.6.1 View Point behind Selection of the Subject 23-24 1.7 Problems of Research 24 1.8 Formation of the area of Research 24-25 1.9 Thoughts of Research 25-41 1.9.1 Value of Caste in Society 26-28 1.9.2 Sociological Meaning of Caste 28 1.9.3 Definition of Caste 28-30 -

Vallabhbhai Patel

VALLABHBHAI PATEL : His role and style in Indian politics 1928-1947 Rani Dhavan Shankardass Dissertation submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 1985. ProQuest Number: 11010657 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010657 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This study of Vallabhbhai Patel’s role and style in In dian politics attempts to show how mobilisation of men and materials was achieved by exclusively political means for the attainment of conservative goals and for the prevention of any radical changes. This was done primarily at Patel's ins tance in the face of much opposition from many forces, parti cularly the socialists who sought a more comprehensive pro gramme for a wider section of society. Patel's qualifications for this job lay in his background, his personality and his affinity with certain regions (Chapter I). Several experi ments in controlled mobilisation culminating in the Bardoli Satyagraha showed the political effectiveness of Patel's ver sion of Gandhi's nationalist scheme (Chapter II). -

In the Indian Subcontinent

Bull. Org. mond. Sante 1966, 35, 837-856 Bull. Wld Hlth Org. Haemoglobinopathies, Glucose-6-phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency and Allied Problems in the Indian Subcontinent J. B. CHATTERJEA1 The present world-wide interest in haemoglobinopathies and allied disorders has given rise to a very considerable literature over the past two decades. This communication reviews this literature in sofar as it refers to the Indian subcontinent. The most common abnormality is thalassaemia, which hasbeen discovered in all regions under consideration: India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutanand Ceylon. Haemoglobins S, D and Eare also quite common: Hb S has been found mostly in the aboriginal tribes, Hb D in Gujaratis and Punjabis and Hb E in Bengalis, Assamese and Nepalese. A few instances ofhaemoglobins F, H, J, K, L and Mhave also been reported. However, there remain many population groups to be investigated. Studies of the distribution of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency are also reviewed, and the correlation between the various haem3globin disorders and various environ- mentalfactors is discussed, but it is pointed out that the relevant data are still insufficient to allow any definite conclusions to be drawn. I. INDIA THALASSAEMIA SYNDROMES tion with various abnormal haemoglobins (S, D, E, H, J and K). In most of these cases, the investigations The first instance of thalassaemia in India was started with a patient who was suffering from a recorded by Mukherji (1938) in a Bengali boy. More certain degree of haemolytic anaemia with jaundice precise identification of the disorder was not possible and hepatosplenomegaly. The patient proved to be then and it is not known whether this boy was either homozygous for thalassaemia or a double suffering from homozygous thalassaemia or Hb E heterozygote for the thalassaemia gene and one or thalassaemia. -

Progress of Education in Navsari Taluka

Progress of Education in Navsari Taluka K. M. Kapadia Navsari is a town with a population of 44, 663 according to the Census of 1951. It is a small town with all urban amenities. There are 11 Primary schools, two Anglo-Vernacular schools, six High schools, of which two are specially for girls, a college with units for Arts and Science courses and a Technical school. There are four libraries—two of them having more than ten thousand books each. Three cinema houses cater for public entertainment. There are two public hospitals, one of them being run by the Government, and five private ones, of which two are for eyes and three for general surgery. Two of the latter are equipped with X-ray apparatus. There are two public maternity hospitals, one for the Parsis and the other for the Hindus, besides three private maternity homes. Since 1923, electricity is available for the most part of the day for lighting and sundry industrial activities which require electrical power. Water supply was introduced in January 1929 and underground drainage was completed by 1934-35. There are five banks including a Land Mortgage Bank which started functioning in 1938. The town has two textile mills, one established in 1932 and the other in 1938. They provide employment to about three thousand workers. There are a 'metal works, ' two bobbin factories, two saw mills and about twenty small industrial concerns. Before the merger of States, Navsari was the district headquarter of Navsari division (prant). It was also the taluka headquarter of Navsari taluka, comprising 78 villages. -

Paul Deussen

Appendix Lambda: The Brahmin Intellectual Line Connecting brothers of Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity at Cornell University, tracing their fraternal Big Brother/Little Brother line to tri-Founder John Andrew Rea (1869) Mahlon Gaylord Peters (1872) of the founding generation at Phi Kappa Psi, Cornell . . was infatuated with Friedrich Nietzche, . Govinda was influenced by Sevappa the fraternity brother of our Carl Schurz Nayak . (1870) . Cousin Friedrich was close friends . Sevappa followed in the tradition o with Paul Deussen . Achyuta Raya of Vijayanagara . Paul was influenced by Arthur . Achyuta was influenced by Krishna Schopenhauer . Deve Raya . . Schopenhauer was influenced by the . Krishna Deva Raya followed in the Indian scholar Govinda Dikshita . tradition of Saluva Timmarusu . Below we present short biographies of the Brahmin intellectual line of the Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity at Cornell University. “Who defends the House.” Brother Mahlon Peters, the great Stroker, read Fatum und Geschichte (1862) and Willensfreiheit und Fatum (1862) as an undergraduate, and formed a lifelong interest in Friedrich Nietzche, the fraternity brother of New York Alpha’s Carl Christian Schurz (1870): Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was born on October 15, 1844, in Röcken, a small town near Lützen, in the Prussian part of Saxony. His father, Karl Ludwig Nietzsche, had only recently arrived in Röcken, having been appointed pastor through the personal recommendation of Friedrich Wilhelm IV, King of Prussia, who had recognized Karl Ludwig's talents while serving as tutor in the ducal court at Altenberg. In his new position as pastor for Röcken and several surrounding villages, Karl Ludwig recognized the need to settle down. -

Bhulabhai Desai

smjftcP TTTCH Pmfdl BUILDERS OF MODERN INDIA 'Blt^W 'ot’m <Hldddl Hi^Hl «qtoSKj spadaicJ Ss±be-sS*Sj smjfW HKd^ f>leM<*>K aitjS»« 01610© BUILDERS OF MODERN INDIA an^Pif 2i»03C3 Bhulabhai Desai epa D3d M.C.Setalvad ^9110 [5 6XJ LJ IT rj£5 £ rfl'jp LjI 60 6TT 000160(0(5) (D1<5(BZIO<D)0*66)o3 ^>e& eDcr^^^Sc^o _ojt c cjT pfr .^tXJL fr» >A-j a p- 3TT^ra> *TRd PlHfdl BUILDERS OF MODERN INDIA veldd^ =Hl^Ft4 dttddl Hid HI «j£Sks epsdicJ SsSae-aWcb 3nq;f^n?> dKd^ RlcMd-K 0©0© g>?flOI 3fig^R5 - *TR?TRJ PWdN: 7>^'-WTW3 ^ feBVT^T IT)6xii_iit rj^1ir)i_flff)6iT cnoieocxo) (nl^aao<0)o<eoa3 ^>eS oOo»^<5cx> —a*—o ^.S* pfo. .^iXJL fr> lA-jiA-p- 'HKd Pi*ifdl BUILDERS OF MODERN INDIA s»td(^S3 T?%t '5|1^s bH'SH frlfot 5Hl^pL4 <HUddl Hi^HI tsqbZti apad^cd SstoE’zk ——1 ..■-."■- o©©© ©dfiGi anqf _ _y #■ fe^Kr^T r& 6XJ i_i rr jj$5 & #1 n 6fr cnaieora®) (rfl<3in20<D>0ce©c/8 BUILDERS OF MODERN INDIA BHULABHAIDESAI M.C. SETALVAD PUBLICATIONS DIVISION MINISTRY OF INFORMATION & BROADCASTING GOVERNMENT OF INDIA First Edition 1981 (Saka 1902) First Reprint 1990 (Saka 1912) Second Reprint 1999 (Saka 1921) Third Reprint 2010 (Saka 1931) © Publications Division ISBN : 978-81-230-1608-5 BMI-ENG-REP-044-2009-10 Price : Rs. 220.00 Published by The Additional Director General (In-charge), Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, Soochna Bhawan, C.G.O.