Bhulabhai Desai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

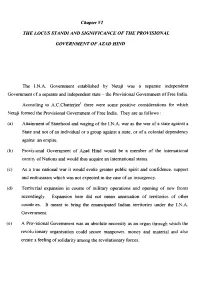

Chapter VI the LOCUS STANDI and SIGNIFICANCE of THE

Chapter VI THE LOCUS STANDI AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT OFAZAD HIND The l.N.A. Government established by Netaji was a separate independent Government cf a separate and independent state - the Provisional Government of Free India. According to A.C.Chatterjee' there were some positive considerations for which Netaji formed the Provisional Government of Free India. They are as follows : (a) Attainment of Statehood and waging of the l.N.A. war as the war of a state against a State and not of an individual or a group against a state, or of a colonial dependency agains; an empire. (b) Provisional Government of Azad Hind would be a member of the international comit> of Nations and would thus acquire an international status. (c) As a tj'ue national war it would evoke greater public spirit and confidence, support and enthusiasm which was not expected in the case of an insurgency. (d) Territorial expansion in course of military operations and opening of new fronts accordingly. Expansion here did not mean annexation of territories of other countr es. It meant to bring the emancipated Indian territories under the l.N.A. Government. (e) A Pro^'isional Government was an absolute necessity as an organ through which the revoluionary organisation could secure manpower, money and material and also create a feeling of solidarity among the revolutionary forces. 174 (f) It also provided one central authority for coordinating the forces of the revolutionaries. This was one thing which was lacking in India's First War of Independence in 1857. (g) Besides, through alliance with other Governments it could secure special assistance from friendly countries. -

UNIT 1 UNITY and DIVERSITY Unity and Diversity

UNIT 1 UNITY AND DIVERSITY Unity and Diversity Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Concepts of Unity and Diversity 1.2.1 Meaning of Diversity 1.2.2 Meaning of Unity 1.3 Forms of Diversity in India 1.3.1 Racial Diversity 1.3.2 Linguistic Diversity 1.3.3 Religious Diversity 1.3.4 Caste Diversity 1.4 Bonds of Unity in India 1.4.1 Geo-political Unity 1.4.2 The Institution of Pilgrimage 1.4.3 Tradition of Accommodation 1.4.4 Tradition of Interdependence 1.5 Let Us Sum Up 1.6 Keywords 1.7 Further Reading 1.8 Specimen Answers to Check Your Progress 1.0 OBJECTIVES After studying this unit you should be able to z explain the concept of unity and diversity z describe the forms and bases of diversity in India z examine the bonds and mechanisms of unity in India z provide an explanation to our option for a composite culture model rather than a uniformity model of unity. 1.1 INTRODUCTION This unit deals with unity and diversity in India. You may have heard a lot about unity and diversity in India. But do you know what exactly it means? Here we will explain to you the meaning and content of this phrase. For this purpose the unit has been divided into three sections. In the first section, we will specify the meaning of the two terms, diversity and unity. 9 Social Structure Rural In the second section, we will illustrate the forms of diversity in Indian society. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Rrb Ntpc Top 100 Indian National Movement Questions

RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS Stay Connected With SPNotifier EBooks for Bank Exams, SSC & Railways 2020 General Awareness EBooks Computer Awareness EBooks Monthly Current Affairs Capsules RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS Click Here to Download the E Books for Several Exams Click here to check the topics related RRB NTPC RRB NTPC Roles and Responsibilities RRB NTPC ID Verification RRB NTPC Instructions RRB NTPC Exam Duration RRB NTPC EXSM PWD Instructions RRB NTPC Forms RRB NTPC FAQ Test Day RRB NTPC TOP 100 INDIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT QUESTIONS 1. The Hindu Widows Remarriage act was Explanation: Annie Besant was the first woman enacted in which of the following year? President of Indian National Congress. She presided over the 1917 Calcutta session of the A. 1865 Indian National Congress. B. 1867 C. 1856 4. In which of the following movement, all the D. 1869 top leaders of the Congress were arrested by Answer: C the British Government? Explanation: The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act A. Quit India Movement was enacted on 26 July 1856 that legalised the B. Khilafat Movement remarriage of Hindu widows in all jurisdictions of C. Civil Disobedience Movement D. Home Rule Agitation India under East India Company rule. Answer: A 2. Which movement was supported by both, The Indian National Army as well as The Royal Explanation: On 8 August 1942 at the All-India Indian Navy? Congress Committee session in Bombay, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi launched the A. Khilafat movement 'Quit India' movement. The next day, Gandhi, B. -

Congress Activities 1944

Congress Activities 1944 Congressmen in Gujerat Districts have been returned unopposed during the recent elections to local bodies. A statement issued in this connection by prominent Congressmen of Gujerat like Jiwanlal H. Diwan and Khandubhai K. Desai declares that the underlying intention of contesting these elections is not to work the adminstration of these bodies but to show the extent of Congress influence over the public, the people's faith in the Congress policy and hatred towards the present policy of Government. The Gujerat Congress Seva Dal opened a “Workers' Training Class” in the premises of the Gujerat Vidyapith, Ahmedabad, from May 5th. About 100 candidates have joined. An informal meeting of about 50 Congressmen was held at Bombay on May 9th under the presidentship of Nagindas T. Master when resolutions were adopted (1) reiterating the unflinching faith of Congressmen in Gandhi's leadership and (2) exhorting all Congressmen to continue the constructive programme of the Congress, offer help to the victims of the recent explosions and render assistance in redressing the hardship caused by food shortage, famine and disease. M. R. Masani, H. R. Pardiwala, Joachim Alva, Mrs. Violet Alva and Ishwarbhai S. Patel were prominent amongst those attended. At Poona about 25 Congressmen assembled on May 21st under the presidentship of V. P. Limaye and appointed a Committee with B. M. Gupte as President and A. T. Dandavate as Secretary to organise collections for the Kasturba Memorial Fund and 5,000 spindles of yarn to be presented to M. K. Gandhi on his next birth-day. The Committee further decided to take up mass spinning and render all possible assistance to Rashtra Seva Dal Branches. -

Nehru and the New Commonwealth Eighth Lecture - by Sir Harold Wilson 2 November 1978

Nehru and the New Commonwealth Eighth Lecture - by Sir Harold Wilson 2 November 1978 In accepting the honour of being invited to give the annual Nehru Memorial Lecture I do not have the advantage of most of those who have gone before me. Unlike Lord Butler and Krishna Menon, I was not born in India. Unlike some who have delivered the lecture, I did not know Nehru in the long years of struggle towards Independence. I did come to know him quite well through his visits to Commonwealth Conferences when I was a member of Clement Attlee's Cabinet. I remember those conferences to which you referred, 1948 and 1949, following which the Constituent Assembly in New Delhi ratified the declaration of the Prime Minister announcing India's adherence to the Commonwealth of Nations. In those days the Commonwealth Conference did not meet in the spacious surroundings of Marlborough House or Lancaster House, but round the cabinet table in Downing Street, with plenty of room not only for Prime Ministers but Foreign Ministers and officials as well. I remember the one I attended when first Nehru was there. There were nine nations represented there, including Southern Rhodesia which, while not technically and juridically independent, had a great measure of autonomy except in foreign affairs. Impressions of Nehru and Krishna Menon The Commonwealth Conferences I chaired as Prime Minister in the 1960s rose in number from 21 attenders to 36. The last one I attended in Jamaica in 1975 was attended by 33 countries, Nehru being absent, and since then two new hitherto dependent territories qualified for membership of the Commonwealth. -

Address by the President of India, Shri Pranab Mukherjee at the Farewell Function

ADDRESS BY THE PRESIDENT OF INDIA, SHRI PRANAB MUKHERJEE AT THE FAREWELL FUNCTION CENTRAL HALL IN PARLIAMENT HOUSE, NEW DELHI, JULY 23, 2017 1. Honourable Members, I would like to acknowledge my deep gratitude and appreciation to Honourable Speaker and the Honourable Chairman, Rajya Sabha and Honourable Members of Parliament for organizing this farewell ceremony on the eve of my demitting office as the 13th President of the Republic of India. 2. Honourable Members, I am a creation of this Parliament. It shaped my political outlook and persona. Bear with me if I feel nostalgic and indulge myself by going back to the past. On 26th January 1950, the Constitution of India came into effect. In a remarkable display of idealism and courage, we the people of India gave to ourselves a sovereign democratic republic to secure to all its citizens justice, liberty and equality. We undertook to promote amongst all citizens fraternity, the dignity of the individual and the unity of the nation. These ideals became the lodestars of the modern Indian state. The Indian Constitution consisting of 395 Articles and 12 Schedules is not merely a legal document for administration but the Magna Carta of socio-economic transformation of the country. It represents the hopes and aspirations of the billion plus Indians. 3. Sixty eight years ago, after the first general election, the Indian Parliament began its journey representing the sovereign will of its people. Both the Houses were constituted, the first President of the Republic was elected who addressed the first Joint Session of the Parliament and the Indian Parliamentary system rolled out. -

The British Partner in the Transfer of Power Ninth Lecture - by the Earl of Listowel 24 June 1980

The British Partner in the Transfer of Power Ninth Lecture - by the Earl of Listowel 24 June 1980 The story of the transfer of power has been told before, but always from the angle of the narrators. I shall follow their example by confining my remarks this evening, apart from a brief sketch of the historical background, to that aspect of the British-Indian relationship I know from my personal experience as a minister in the (wartime) Churchill and Attlee governments. This gave me some insight into the part played by the British Government in its dealings with the Government of India and the Indian political leaders during the final stages. But before I proceed any further I am sure you would wish me to remind you that we are meeting on the eve of what would have been Lord Mountbatten's eightieth birthday. His presence would have been specially appropriate because we shall be recalling what, in the light of history, must surely have been the most outstanding of all his achievements. For it was his consummate statesmanship which made possible the severance of our old ties with India by mutual goodwill, instead of after bitter dissension, which would have left a legacy of rancour and a fractured Commonwealth. He accomplished his task with so much skill and understanding that it bound our two countries in the close friendship we enjoy at the present time. This was brought home to me with startling vividness by the welcome accorded to a parliamentary delegation with which I visited India last year, traversing the country from New Delhi to Chandigarh, and from there to Madras and Bombay. -

Fighting Racism: Black Soldiers and Workers in Britain During the Second World War

Immigrants & Minorities ISSN: 0261-9288 (Print) 1744-0521 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fimm20 Fighting Racism: Black Soldiers and Workers in Britain during the Second World War Gavin Schaffer To cite this article: Gavin Schaffer (2010) Fighting Racism: Black Soldiers and Workers in Britain during the Second World War, Immigrants & Minorities, 28:2-3, 246-265, DOI: 10.1080/02619288.2010.484250 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02619288.2010.484250 Published online: 28 May 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 591 View related articles Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fimm20 Download by: [St Francis Xavier University] Date: 07 September 2016, At: 11:44 Immigrants & Minorities Vol. 28, Nos. 2/3, July/November 2010, pp. 246–265 Fighting Racism: Black Soldiers and Workers in Britain during the Second World War Gavin Schaffer* School of Social, Historical and Literary Studies, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK The Second World War led to a substantial increase in the number of black people living and working in Britain. Existing black British communities were bolstered in this period by the arrival of war volunteer workers from the Empire, who came to serve Britain in a variety of military and civilian roles, as well as by the arrival of 130,000 black GIs in the US army’s invasion force. This article considers the reception that these communities received from the British government and the British general public, questioning the extent to which racial ideas of white difference and superiority continued to shape white British reactions to black workers and soldiers. -

The Shaping of Modern Gujarat

A probing took beyond Hindutva to get to the heart of Gujarat THE SHAPING OF MODERN Many aspects of mortem Gujarati society and polity appear pulling. A society which for centuries absorbed diverse people today appears insular and patochiai, and while it is one of the most prosperous slates in India, a fifth of its population lives below the poverty line. J Drawing on academic and scholarly sources, autobiographies, G U ARAT letters, literature and folksongs, Achyut Yagnik and Such Lira Strath attempt to Understand and explain these paradoxes, t hey trace the 2 a 6 :E e o n d i n a U t V a n y history of Gujarat from the time of the Indus Valley civilization, when Gujarati society came to be a synthesis of diverse peoples and cultures, to the state's encounters with the Turks, Marathas and the Portuguese t which sowed the seeds ol communal disharmony. Taking a closer look at the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the authors explore the political tensions, social dynamics and economic forces thal contributed to making the state what it is today, the impact of the British policies; the process of industrialization and urbanization^ and the rise of the middle class; the emergence of the idea of '5wadeshi“; the coming £ G and hr and his attempts to transform society and politics by bringing together diverse Gujarati cultural sources; and the series of communal riots that rocked Gujarat even as the state was consumed by nationalist fervour. With Independence and statehood, the government encouraged a new model of development, which marginalized Dai its, Adivasis and minorities even further.