Progress of Education in Navsari Taluka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mega Auction Sale Notice 18.03.2021

SALE NOTICE FOR SALE OF ZONAL STRESS ASSETS RECOVERY BRANCH, BARODA IMMOVABLE / MOVABLE PROPERTIES APPENDIX - IV-A [See proviso to Rule 6 (2) & 8 (6)] SURAJ PLAZA-3, 4TH FLOOR, SAYAJIGUNJ, BARODA. PHONE : 0265 - 2360022 / 2360033 E-AUCTION SALE NOTICE FOR SALE OF IMMOVABLE / MOVABLE ASSETS UNDER THE SECURITISATION AND RECONSTRUCTION OF FINANCIAL ASSETS AND ENFORCEMENT OF SECURITY INTEREST ACT, 2002 READ WITH PROVISO TO RULE 6 (2) & 8 (6) OF THE SECURITY INTEREST (ENFORCEMENT) RULES, 2002. E-AUCTION DATE : 18.03.2021, TIME : 02.00 P.M. TO 06.00 P.M. Notice is hereby given to the public in general and in particular to the Borrower (s) and Guarantor (s) that the below described immovable / movable property mortgaged / charged to the Secured Creditor, possession of which has been taken by the Authorised Officer of Bank of Baroda, Secured Creditor, will be sold on “As is where is”, “As is what is”, and “Whatever there is” for recovery of below mentioned account/s. The details of Borrower/s / Guarantor/s / Secured Asset/s / Dues / Reserve Price / e-Auction Date & Time, EMD and Bid Increase Amount are mentioned below : Sr. / Reserve Price Status of Possession Property Date & Time Lot Name & Address of Borrower/s / Guarantor/s Give short description of the immovable property with known encumbrances, if any Total Dues EMD and (Constructive / Inspection Date of E-Auction No. Bid Increase Amount Physical) & Time 1. M/S. KAY EMCEE ASSOCIATES Office No. 105, First Floor of city Enclave residential and commercial complex, Opp. Polo Ground, Nr. Baroda High Rs. 18.03.2021 3,29,03,330.15 Rs. -

List of Approved Registered Graduates of Commerce Faculty 2017, Bhuj Taluka

LIST OF APPROVED REGISTERED GRADUATES OF COMMERCE FACULTY 2017, BHUJ TALUKA Sr. No. Name Address Taluka Reg No Challan No ACHARYA MALHAR DWIDHAMESHWAR BHUJ 992 1 PRAFULBHAI COLONY, BHUJ ACHARYA NANDISH 366/B BHUJ 798 BIMALKUMAR ,"NADIGRAM",ODHAV VILL RAW HOUSING, 2 AIYA NAGAR, MUNDRA ROAD,BHUJ,7567569745 ACHARYA RAHUL JUNI RAWALVADI P.L.- BHUJ 440 3 CHANDULAL 270,BHUJ, 814001211 AHALAPARA AT-149-152/2, ODHAV BHUJ 824 DULARI ASHOKBHAI EVENUE, MUNDRA 4 RELOCATION SITE,BHUJ AHALPARA DULARI 149, MUNDRA BHUJ 1055 5 ASHOKBHAI RELOCATION SITE, BHUJ. AHIR MOHINI 72, NRNARAYAN BHUJ 528 GOPALBHAI NAGAR, NR CHABUTRA CHOWK, GARBI CHOWK 6 JUNAVAS, MADHAPAR BHUJ, 9913838887 AHIR SHIVJI GOPAL 24, SHAKTI NAGAR-2, BHUJ 1099 BEHIND SORTHIYA 7 SAMAJWADI,JUNAVAS, MADHPAPAR, BHUJ, 9979980151 AJANI NAYAN SURAL BHIT ROAD, BHUJ 429 8 VASANTLAL MARKET YARD, BHUJ. 8140091211 AJANI VRAJNI JYUBELI HOSPITAL BHUJ 961 VASANTBHAI STREET-1, HATHISTHAN 9 SALA , BHUJ,8511312641 AKHANI POOJABEN 101, AIYA NAGAR, BHUJ 344 NIRANJANBHAI JUNA VAS, MADHAPAR, 10 TALUKA – BHUJ. 9725086947 AMRANI BHAKTI HOUSE NO:6, ANAND BHUJ 1402 KISHANCHAND BHAVAN, VRUNDAVAN PARK SOCIETY,OLD 11 RAILWAY STATION, BHUJ ANTANI CHIRAG 48/53-6, YOGIRAJ PARK BHUJ 580 SIRISHBHAI ,OPP ST WORKSHOP, 12 SANSKAR NAGAR,BHUJ, 9879292898 ANTANI HARASHAL 48-53/6, YOGIRAJ PARK, BHUJ 1343 SHIRISHBHAI OPP. ST WORKSHOP, 13 SANSKAR NAGAR, BHUJ ANTANI HARSHAL 48/53-6, YOGIRAJ PARK, BHUJ 425 SHIRISHBHAI OPPOSITE ST WORK SHOP, SANSKAR NAGAR, 14 BHUJ. 9638553439 9825337877 ANTANI JIGNEY KARISHMA, SANSKAR BHUJ 1200 15 BHASKARBHAI NAGAR 33/A, NEAR ST WORKSHOP, BHUJ. ARODA JITENDRA 331/3 B SANKAR BHUJ 1439 16 KHUSHALCHAND TRECTOR,JUNAVAS MADHAPAR,BHUJ ARUNKUMAR ASHAPURA TOWN SHIP, BHUJ 1559 17 JAGDISHPRASHAD AIRPORT ROAD, BHUJ, H. -

(Spotac), Daman List of Candidates Applie

UT ADMINISTRATION OF DAMAN & DIU SOCIETY FOR PROMOTION OF TOURISM, ART AND CULTURE (SPOTAC), DAMAN LIST OF CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR THE POST OF ACCOUNTANT IN TOURISM DEPARTMENT ON CONTRACT BASIS SR. NAME OF CANDIDATE & ADDRESS DATE OF EDUCATION EXPERIENCE ELIGIBLE NO WITH MOBILE NUMBER BIRTH & AGE QUALIFICATION OR INELIGIBLE WITH REASON 1 2 3 4 5 6 1. Shri Varma Amitkumar Santhoshkumar 22/07/1995 1) BBA 1) Accountant in Hotel Sidharth 27/05/2014 to Ineligible due to H.No.27, Ghelwad Falia, Dabhel, 23 Years & 31/07/2017 EQ. is not available Daman 8 Months 2) Administrative Assistant in Bal Bhawan Board, as required Mob: 8000318142/ 9033777430 Daman from 11/02/2019 to 28/02/2019 E mail: [email protected] 3) Accountant in Silvassa Municipal Council from 01/03/2019 to 14/03/2019 2. Shri Nishit Zaveri 12/05/1990 1) B.Com 1) Jr. Accountant in Himsun Builder Pvt. Ltd., Eligible C-22, Plot No.122, Sai Sidhi Co- 28 years & 2) M.Com Mumbai from 01/07/2012 to 31/07/2014 operative housing society, Near 10 months 3) Company Secretary 2) Asstt. Accountant , Prime Civil Infrastructures Suvidhya School, Gorai Road, Gorai – Executive Programme Pvt. Ltd. , Mumbai from 01/09/2014 to till date II, Borivilli West -400091 Mob: 9930899423/ (022) 26148052 E mail : [email protected] 3 Shri Dharmeshsingh B Solanki 01/02/1983 1) B.Com 1) Accountant –cum-Cashier M/s Popular Hotel, Eligible H.No.155, Dhanlakshmi House, At post 36 Years & Silvassa for 3 years Provisionally on Athola School Faliya, (sili Fatak), 1 Months 2) Head Cashier & Accountant –cum-Manager production of Silvassa Prathmesh Agency, (Hindusthan Petroleum, Naroli) B.com passing Mob.No.9714491947 3) Head Accountant, M/s SSR Memorial Trust, certi. -

UNIT 1 UNITY and DIVERSITY Unity and Diversity

UNIT 1 UNITY AND DIVERSITY Unity and Diversity Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Concepts of Unity and Diversity 1.2.1 Meaning of Diversity 1.2.2 Meaning of Unity 1.3 Forms of Diversity in India 1.3.1 Racial Diversity 1.3.2 Linguistic Diversity 1.3.3 Religious Diversity 1.3.4 Caste Diversity 1.4 Bonds of Unity in India 1.4.1 Geo-political Unity 1.4.2 The Institution of Pilgrimage 1.4.3 Tradition of Accommodation 1.4.4 Tradition of Interdependence 1.5 Let Us Sum Up 1.6 Keywords 1.7 Further Reading 1.8 Specimen Answers to Check Your Progress 1.0 OBJECTIVES After studying this unit you should be able to z explain the concept of unity and diversity z describe the forms and bases of diversity in India z examine the bonds and mechanisms of unity in India z provide an explanation to our option for a composite culture model rather than a uniformity model of unity. 1.1 INTRODUCTION This unit deals with unity and diversity in India. You may have heard a lot about unity and diversity in India. But do you know what exactly it means? Here we will explain to you the meaning and content of this phrase. For this purpose the unit has been divided into three sections. In the first section, we will specify the meaning of the two terms, diversity and unity. 9 Social Structure Rural In the second section, we will illustrate the forms of diversity in Indian society. -

CHAPTER-1 INTRODUCTION Project: M/S

CHAPTER-1 INTRODUCTION Project: M/s. Spectrum Dyes & Chemicals Pvt. Ltd., Palsana, Surat, Gujarat (EIA/EMP Report for Proposed Expansion of Dyes & Chemical Manufacturing Unit) CHAPTER – 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND M/s. Spectrum Dyes & Chemicals Pvt. Ltd. proposes expansion of dyes & chemical manufacturing unit at Block No-484, 502, 503-A, 504 & 505, N.H.No.8, Palsana-394315, Dist.: Surat, Gujarat. As per EIA Notification 2006, the proposed project is categorized as A, 5(f), Synthetic Organic Chemicals industry (Located outside the Notified Industrial Area). This Environmental Impact Assessment study is carried out as a part of the process to obtain Environmental Clearance for the above-mentioned project. A mitigation plan has been prepared and a detailed environmental management plan (EMP) is drawn out to effectively mitigate or minimize potentially adverse environmental impacts. The EIA/EMP Report has been prepared in line with Terms of Reference (ToR) suggested by Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC) MoEF & CC, vide Letter No. IA-J-11011/517/2017-IA-II(I) Dated:-09th December 2017 attached as an Annexure-I and its compliance status is listed in Table 1.1. 1.2 PURPOSE OF EIA The purpose of the EIA study is to critically analyze the manufacturing process of products, proposed to be manufactured with reference to types and quantity of different raw material consumption, possible source of wastewater, air emission and hazardous waste generation, control measures to reduce the pollution and to delineate a comprehensive environment management plan along with recommendations in proposed environment management system. 1.3 OBJECTIVES OF EIA The main objectives of the study are: a) To assess the background environmental status in and around project site. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN 98, MAULANA AZAD AND Andaman & ROAD, PORT BLAIR, NICOBAR Nicobar State 744101, ANDAMAN & 943428146 ISLAND ANDAMAN Coop Bank Ltd NICOBAR ISLAND PORT BLAIR HDFC0CANSCB 0 - 744656002 HDFC BANK LTD. 201, MAHATMA ANDAMAN GANDHI ROAD, AND JUNGLIGHAT, PORT NICOBAR BLAIR ANDAMAN & 98153 ISLAND ANDAMAN PORT BLAIR NICOBAR 744103 PORT BLAIR HDFC0001994 31111 ANDHRA HDFC BANK LTD6-2- 022- PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD 57,CINEMA ROAD ADILABAD HDFC0001621 61606161 SURVEY NO.109 5 PLOT NO. 506 28-3- 100 BELLAMPALLI ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH BELLAMPAL 99359 PRADESH ADILABAD BELLAMPALLI 504251 LI HDFC0002603 03333 NO. 6-108/5, OPP. VAGHESHWARA JUNIOR COLLEGE, BEAT BAZAR, ANDHRA LAXITTIPET ANDHRA LAKSHATHI 99494 PRADESH ADILABAD LAXITTIPET PRADESH 504215 PET HDFC0003036 93333 - 504240242 18-6-49, AMBEDKAR CHOWK, MUKHARAM PLAZA, NH-16, CHENNUR ROAD, MANCHERIAL - MANCHERIAL ANDHRA ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH MANCHERIY 98982 PRADESH ADILABAD PRADESH 504208 AL HDFC0000743 71111 NO.1-2-69/2, NH-7, OPPOSITE NIRMAL ANDHRA BUS DEPO, NIRMAL 98153 PRADESH ADILABAD NIRMAL PIN 504106 NIRMAL HDFC0002044 31111 #5-495,496,Gayatri Towers,Iqbal Ahmmad Ngr,New MRO Office- THE GAYATRI Opp ANDHRA CO-OP URBAN Strt,Vill&Mdl:Mancheri MANCHERIY 924894522 PRADESH ADILABAD BANK LTD al:Adilabad.A.P AL HDFC0CTGB05 2 - 504846202 ANDHRA Universal Coop Vysya Bank Road, MANCHERIY 738203026 PRADESH ADILABAD Urban Bank Ltd Mancherial-504208 AL HDFC0CUCUB9 1 - 504813202 11-129, SREE BALAJI ANANTHAPUR - RESIDENCY,SUBHAS -

Industrial Policy 2015 Industrial Daman & Diu and Policy Dadra & Nagar Haveli 2015

Daman & Diu and Dadra & Nagar Haveli Industrial Policy 2015 Industrial Daman & Diu and Policy Dadra & Nagar Haveli 2015 Page | 01 1. BACKROUND 1. Naonal Context 03 1.1 Overview 04 1.2 Investment Opportunies 06 1.2.1 Industry in Daman & Diu and Dadra & Nagar Haveli 06 1.2.2 Tourism 07 1.3 Present Industrial Profile 08/09 1.4 Advantage over other states 10 1.5 Challenges 10 2. FOCUS AREAS 2.1 Objecve 12 2.2 Vision 12 2.3 Mission 12 2.4 Policy Objecves 13 2.5 Policy Targets 13 2.6 Thrust Areas 14 2.7 Classificaon of Industries 14 2.8 Proposed Intervenons 14 2.8.1 Investor Facilitaon 15 2.8.1.1 Salient features of the Daman & Diu and Dadra & Nagar Niveshak Sugamta Portal 15/16 2.8.1.2 Investment promoon council (IPC) 17/18/19 2.8.2 Land Pooling and Efficient Land use 20 2.8.3 Infrastructure 20 2.8.3.1 Cargo Movement, Logiscs, Road Network 21 2.8.3.2 Power 21 2.8.3.3 Piped Natural Gas 22 2.8.3.4 Water supply & Sewage 22 2.8.4 Minimizing Transacon Cost 23 2.8.5 Skill Development 24 2.8.6 Tourism Infrastructure 25 2.8.7 Technology And Innovaon 25 2.8.8 Small And Medium Enterprises and Labour Intensive Industry 25 3. SUPPORT & BENEFIT TO INDUSTRIES 3 Investment Promoon Scheme 26 Commied to India Map Page | 02 1 NATIONAL CONTEXT In the post 1991 period, the Indian economy has witnessed remarkable economic growth, riding on the strength of huge private investments, infrastructure improvements and regulatory changes. -

C1-27072018-Section

TATA CHEMICALS LIMITED LIST OF OUTSTANDING WARRANTS AS ON 27-08-2018. Sr. No. First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio / BENACC Amount 1 A RADHA LAXMI 106/1, THOMSAN RAOD, RAILWAY QTRS, MINTO ROAD, NEW DELHI DELHI 110002 00C11204470000012140 242.00 2 A T SRIDHAR 248 VIKAS KUNJ VIKASPURI NEW DELHI 110018 0000000000C1A0123021 2,200.00 3 A N PAREEKH 28 GREATER KAILASH ENCLAVE-I NEW DELHI 110048 0000000000C1A0123702 1,628.00 4 A K THAPAR C/O THAPAR ISPAT LTD B-47 PHASE VII FOCAL POINT LUDHIANA NR CONTAINER FRT STN 141010 0000000000C1A0035110 1,760.00 5 A S OSAHAN 545 BASANT AVENUE AMRITSAR 143001 0000000000C1A0035260 1,210.00 6 A K AGARWAL P T C P LTD AISHBAGH LUCKNOW 226004 0000000000C1A0035071 1,760.00 7 A R BHANDARI 49 VIDYUT ABHIYANTA COLONY MALVIYA NAGAR JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 302017 0000IN30001110438445 2,750.00 8 A Y SAWANT 20 SHIVNAGAR SOCIETY GHATLODIA AHMEDABAD 380061 0000000000C1A0054845 22.00 9 A ROSALIND MARITA 505, BHASKARA T.I.F.R.HSG.COMPLEX HOMI BHABHA ROAD BOMBAY 400005 0000000000C1A0035242 1,760.00 10 A G DESHPANDE 9/146, SHREE PARLESHWAR SOC., SHANHAJI RAJE MARG., VILE PARLE EAST, MUMBAI 400020 0000000000C1A0115029 550.00 11 A P PARAMESHWARAN 91/0086 21/276, TATA BLDG. SION EAST MUMBAI 400022 0000000000C1A0025898 15,136.00 12 A D KODLIKAR BLDG NO 58 R NO 1861 NEHRU NAGAR KURLA EAST MUMBAI 400024 0000000000C1A0112842 2,200.00 13 A RSEGU ALAUDEEN C 204 ASHISH TIRUPATI APTS B DESAI ROAD BOMBAY 400026 0000000000C1A0054466 3,520.00 14 A K DINESH 204 ST THOMAS SQUARE DIWANMAN NAVYUG NAGAR VASAI WEST MAHARASHTRA THANA -

The Structure of Indian Society: Then And

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 The Structure of Indian Society Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 ii The Structure of Indian Society Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 The Structure of Indian Society Then and Now A. M. Shah LONDON NEW YORK NEW DELHI Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 First published 2010 by Routledge 912 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Transferred to Digital Printing 2010 © 2010 A. M. Shah Typeset by Star Compugraphics Private Limited D–156, Second Floor Sector 7, Noida 201 301 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-415-58622-1 Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 To the memory of Purushottam kaka scholar, educator, reformer Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 vi The Structure of Indian Society Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 Contents Glossary ix Acknowledgements xiii Introduction 1 1. -

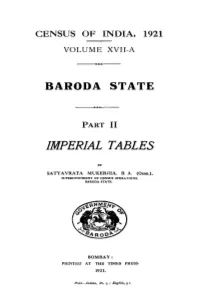

Baroda State, Imperial Tables, Part II, Vol-XVII-A

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1921 VOLUME XVII-A BARODA STATE PART II IMPERIAL TABLES BY SATYAVRATA MUKERJEA, B. A. (Oxon.). SUPBRINTENDENT OF CBNSUS OPBRATIONS, BARODA STATE. BOMBAY; PRINTED AT THE TIMES PRESS. 1921. PriCe-Indian, Rs. 9 .. Eng-lisk, 9 s. TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE TA.BLE I.-Area. Houses and Population .. 1 II.-Variation in Population since 1872 3 III.-Towns and Villages Classified by Population 5 " IV.-Towns Classified by Population. with Variation since 1872 .. 7 V.-Towns Arranged Territorially with Population by Religion " 9 VI.-Religion " 13 VII.-Age, Sex and Civil Condition- \ Part A-State Summary .. 16 •• B--Details for Divisions 22 " C-Details for the City of Baroda 28 VIII.-Education by Religion and Age- .. Part A-State Summary 32 " B-Details for Divisions 34 " C-Details for the City of Baroda 37 IX.-Education by Selected Castes, Tribes or Races ~g " X.-Language 43 XI.-Birth-Place 47 " XII.-Infirmities- Part I.-Distribution by A.ge 54 " II.-Distribution by Divisions 54 XII-A.-Infirmities by Selected Castes, Tribes or Races 55 " XIlL-Caste, Tribe, Race or Nationality- .. Part A-Hindu, .Jain, Animist and Hindu Arya 58 " B-Musalman 62 XIV.-Civil Condition by Age for Selected Castes 63 " .. XV.-Christians by Sect and Race 71 .. XVI.-Europeans and Anglo-Indians by Race and Age 75 XVII.-Occupation or Means of Livelihood 77 " .. XVIIL-Subsidiary Occupations of Agriculturists 99 Actual Workers only (1) Rent Receivers 100 (2) Rent Payers 100 (3) Agricultural Labourers 102 XIX.-Showing for certain Mixed Occupations the Number of Persons who " returned each as their (a) principal and (b) subsidiary Means of Livelihood 105 XX.-Distribution by Religion of Workers and Dependents in Different " Occupations 107 XXI.-Occupation by Selected Castes, Tribes or Races 113 " XXII.-Industrial Sta.tistics- " Part I-Etate Summary 124 " II-Distribution by Divisions 127 " III-Industrial Establishments classified according to the class of Owners and Managers . -

331 CRC Information for LCD Projector.Xlsx

List of CRCs for supply, installation, commissioning and maintenance of LCD Projector Cluster HQ School S.No. District Name Block Name Cluster Name Cluster Head Quarter School Name CRC Co name CRC Contact Mob No DISE Code 1 AHMADABAD BARVALA KHAMBHADA KHAMBHADA 24070801102 UTPALBHAI BHAMBHA 9998341100 2 AHMADABAD BAVLA ADARODA ADARODA 24071000101 BHARATBHAI PRAJAPATI 9510041601 3 AHMADABAD BAVLA BAGODARA BAGODARA 24071000301 HARESHBHAI PARMAR 9824830593 4 AHMADABAD BAVLA BALDANA BALDANA 24071000401 NARENDRABHAI LEUVA 9724786167 5 AHMADABAD BAVLA BHAYALA BHAYALA 24071000802 INDRAJITSINH PADHERIYA 9924082283 6 AHMADABAD BAVLA CHIYADA CHIYADA 24071001001 SAILESHBHAI PATEL 9925742817 7 AHMADABAD BAVLA DURGI (DHARJI) DURGI (DHARJI) 24071001701 PRAHLADBHAI GAJJAR 9724031677 8 AHMADABAD BAVLA METAL METAL 24071003801 PATEL AARTIBEN 9428351863 MUKHYA KUMAR 9 AHMADABAD BAVLA MUKHYA KUMAR BAVLA 24071000604 BHARTIBEN PANDYA 7383833019 BAVLA NAGAR PRATHMIK 10 AHMADABAD BAVLA NAGAR PRATHMIK SHALA 24071000605 SAILESHBHAI PATEL 9925742817 SHALA 11 AHMADABAD BAVLA SHIYAL - 1 SHIYAL - 1 24071005501 RAMESHBHAI GOHIL 8733005994 12 AMRELI AMRELI DEVRAJIYA DEVRAJIYA PRA SHALA 24130101601 VIJAYDAN GADHAVI 9978498063 13 AMRELI JAFRABAD SAGAR SAGAR PAY CENTER SHALA 24130501605 SACHINBHAI MAHETA 8460139452 14 AMRELI LATHI DAMNAGAR 2 DAMANGAR 2 PAY CENTRAL SHALA 24130801304 BHARATBHAI BAVISI 9427429511 15 AMRELI LATHI DHAMEL DHAMEL PAY CENTER SHALA 24130801501 PRAVINBHAI BHESANIYA 9426129744 16 AMRELI LATHI LATHI TALUKA LATHI TALUKA SHALA 24130803003 DEVASIBHAI -

Resettlement Action Plan

FINAL RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN Mumbai- Ahmedabad High Speed Railway Project August 10, 2018 Prepared For: National High-Speed Rail Corporation Limited (NHSRCL) Prepared by: Arcadis India Private Limited Resettlement Action Plan, Mumbai Ahmedabad High Speed Rail QUALITY ASSURANCE Issue Number Reviewed & Date Prepared By /Status Authorised by N K Singh Lalita Pant Joshi 10 August, Version 3.0 Mainak Hazra 2018 Dr Rajani Iyer Rajneesh Kumar i Resettlement Action Plan, Mumbai Ahmedabad High Speed Rail DISCLAIMER The contents of this report document have been prepared with reasonable skill, care and due diligence and information based on the observations during survey, field visits and interviews with stakeholders. The findings, results, observations, conclusions and recommendations given in this report are based on our best professional knowledge as well as information available at the time of the study. The interpretations and recommendations are based on our experience, using reasonable professional skill and judgment, and based upon the information that was available to us and collected during the survey. Therefore, we reserve the right to modify aspects of the report, including the recommendations, if and when new information may become available from ongoing work in field, or pertaining to this project. Neither Arcadis nor any shareholder, director or employee undertakes any responsibility arising in any way whatsoever to any person or organization other than the (Client) and parties in respect of information set out in this report, including any errors or omissions therein arising through negligence or otherwise however caused. i Resettlement Action Plan, Mumbai Ahmedabad High Speed Rail TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................