Vallabhbhai Patel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discussion Questions for Gandhi

Discussion Questions for Gandhi Some of the major characters to watch for: Mohandas Gandhi (aka “Mahatma” or “Bapu”), Kasturba Gandhi (his wife), Charlie Andrews (clergyman), Mohammed Jinnah (leader of the Muslim faction), Pandit Nehru (leader of the Hindu faction—also called “Pandi-gi”), Sardar Patel (another Hindu leader), General Jan Smuts, General Reginald Dyer (the British commander who led the Massacre at Amritzar), Mirabehn (Miss Slade), Vince Walker (New York Times reporter) 1. Gandhi was a truly remarkable man and one of the most influential leaders of the 20th century. In fact, no less an intellect than Albert Einstein said about him: “Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth.” Why him, this small, unassuming man? What qualities caused tens of millions to follow him in his mission to liberate India from the British? 2. Consider Gandhi’s speech (about 30 minutes into the film) to the crowd regarding General Smuts’s new law (fingerprinting Indians, only Christian marriage will be considered valid, police can enter any home without warrant, etc.). The crowd is outraged and cries out for revenge and violence as a response to the British. This is a pivotal moment in Gandhi’s leadership. What does he do to get them to agree to a non-violent response? Why do they follow him? 3. Consider Gandhi’s response to the other injustices depicted in the film (e.g., his burning of the passes in South Africa that symbolize second-class citizenship, his request that the British leave the country after the Massacre at Amritzar, his call for a general strike—a “day of prayer and fasting”—in response to an unjust law, his refusal to pay bail after an unjust arrest, his fasts to compel the Indian people to change, his call to burn and boycott British-made clothing, his decision to produce salt in defiance of the British monopoly on salt manufacturing). -

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Gandhi Warrior of Non-Violence P

SATYAGRAHA IN ACTION Indians who had spent nearly all their lives in South Africi Gandhi was able to get assistance for them from South India an appeal was made to the Supreme Court and the deportation system was ruled illegal. Meantime, the satyagraha movement continued, although more slowly as a result of government prosecution of the Indians and the animosity of white people to whom Indian merchants owed money. They demanded immediate payment of the entire sum due. The Indians could not, of course, meet their demands. Freed from jail once again in 1909, Gandhi decided that he must go to England to get more help for the Indians in Africa. He hoped to see English leaders and to place the problems before them, but the visit did little beyond acquainting those leaders with the difficulties Indians faced in Africa. In his nearly half year in Britain Gandhi himself, however, became a little more aware of India’s own position. On his way back to South Africa he wrote his first book. Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule. Written in Gujarati and later translated by himself into English, he wrote it on board the steamer Kildonan Castle. Instead of taking part in the usual shipboard life he used a packet of ship’s stationery and wrote the manuscript in less than ten days, writing with his left hand when his right tired. Hind Swaraj appeared in Indian Opinion in instalments first; the manuscript then was kept by a member of the family. Later, when its value was realized more clearly, it was reproduced in facsimile form. -

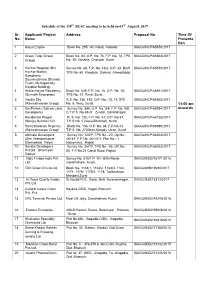

Schedule of the 338Th SEAC Meeting to Be Held on 03Rd Augestl, 2017 Sr. No. Applicant/ Project Name Address Proposal No Time Of

Schedule of the 338th SEAC meeting to be held on 03rd Augestl, 2017 Sr. Applicant/ Project Address Proposal No Time Of No. Name Presenta tion 1 Aarya Empire Block No. 255, Vill. Kalali, Vadodar SIA/GJ/NCP/65870/2017 2 Green Tulip (Green Block No. 83, O.P. No. 78, F.P. No. 78, TPS SIA/GJ/NCP/65903/2017 Group) No. 30, Vanakla, Choryasi, Surat. 3 Harihar Hospital, Shri Survey No. 68, F.P. No. 43/2, O.P. 43, Draft SIA/GJ/NCP/65910/2017 Harihar Maharj TPS No. 60, Khodiyar, Daskroi, Ahmedabad Kamdhenu Dausevashram Dharmik Trust ( Multispecialty Hospital Building) 4 Ashtavinayak Residency Block No. 649, F.P. No. 18, O.P. No. 18, SIA/GJ/NCP/65911/2017 (Sumukh Enterprise) TPS No. 12 ,Puna, Surat. 5 Vanilla Sky R.S. No. 136, 143, O.P. No.; 15, 16 TPS SIA/GJ/NCP/65925/2017 (Rameshwaram Group) No. 5, Vesu, Surat. 11:00 am 6 DevParam ( Soham Land Survey No. 384, O.P. No.159, F.P. No.159, SIA/GJ/NCP/65934/2017 onwards Developers) D.T.P.S. No-69 At Zundal, Gandhinagar, 7 Residential Project R. S. No: 132, F.P. No: 57, O.P. No 57, SIA/GJ/NCP/64135/2017 (Sanjay Surana Huf) T.P.S No: 5 (Vesu-Bhimrad), Surat 8 Rameshwaram Regency Block No. 136, O.P. No. 38, F.P.No.41, SIA/GJ/NCP/65980/2017 (Rameshwaram Group) T.P.S. No. 27(Utran-Kosad), Utran, Surat 9 Ultimate Developers Survey No: 120/P, TPS No.:-20, Op.No.- SIA/GJ/NCP/66003/2017 (Shri Virendrakumar 46+47, F.P.No.-46+47/1, Plot No.:- 1, Manharbhai Patel) Nanamava, Rajkot 10 Savalia Developers Survey No: 267/P, TPS No.:-06, OP.No.- SIA/GJ/NCP/66023/2017 Pvt.Ltd Dharmesh 05, F.P.No.21 Canal Road, Rajkot. -

Sr No YRC TRADE NAME SEAT NO FIRST NAM E NAME LAST NAME

FIRST_NAM Sr No YRC TRADE_NAME SEAT_NO NAME LAST_NAME BIRTH_DATE ADDRESS1 ADDRESS2 ADDRESS3 ADDRESS4 PIN TRIAL_NO GTOTAL ITI_NAME E COMPUTER 303, NR. VARACHH OPERATOR CUM VISHNUKU 1 2011 464409001 PATEL MAULIK 07/04/1990 SNEHMILA NILAM HIRABAG A RD, 395006 1 133 HAJIRA PROGRAMMING MAR N APP BAG SOC. SURAT ASSISTANT COMPUTER OPP. OUSE,HO OPERATOR CUM E-1/13 2 2011 464409002 RAJPUT GAGAN DANSING 12/01/1990 MANTHA NEY PARK SURAT 395009 1 130 HAJIRA PROGRAMMING SMS QTR N RAW H RD ASSISTANT COMPUTER OPERATOR CUM KHUMANBH AT TA MANDVI 3 2011 406409001 CHAUDHARI ANITABEN 15/11/1991 DI SURAT 0 1 138 PROGRAMMING AI MANDVI MANDVI (SURAT) ASSISTANT COMPUTER OPERATOR CUM GUNVANT AT PO FALIYU TA MANDVI 4 2011 406409002 CHAUDHARI JASHUBHAI 08/06/1986 DI SURAT 0 1 138 PROGRAMMING IBEN VANSKUI DADRI BARDOLI (SURAT) ASSISTANT COMPUTER OPERATOR CUM KALPANA AT PO TA MANDVI 5 2011 406409003 CHAUDHARI VIJAYBHAI 01/09/1987 FA BAVDI DI SURAT 0 1 141 PROGRAMMING BEN VANSKUI BARDOLI (SURAT) ASSISTANT Surat FIRST_NAM Sr No YRC TRADE_NAME SEAT_NO NAME LAST_NAME BIRTH_DATE ADDRESS1 ADDRESS2 ADDRESS3 ADDRESS4 PIN TRIAL_NO GTOTAL ITI_NAME E COMPUTER OPERATOR CUM PRATIKKU AT PO NAVA TA DIST MANDVI 6 2011 406409004 CHAUDHARI RUSANBHAI 09/10/1993 0 1 135 PROGRAMMING MAR KHAROLI FALIYA MANDVI SURAT (SURAT) ASSISTANT COMPUTER AT PO OPERATOR CUM REKHABE TA MANDVI 7 2011 406409005 CHAUDHARI DINESHBHAI 07/09/1992 FALI NISHAL DI SURAT 0 1 132 PROGRAMMING N MANDVI (SURAT) FALIYU ASSISTANT COMPUTER TA AMUHIK OPERATOR CUM AT PO- MANDVI 8 2011 406409006 CHAUDHARI SHARMILA LALJIBHAI 10/01/1985 MANDVI A.C. -

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi's Experiments with the Indian

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi’s Experiments with the Indian Economy, c. 1915-1965 by Leslie Hempson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Co-Chair Professor Mrinalini Sinha, Co-Chair Associate Professor William Glover Associate Professor Matthew Hull Leslie Hempson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5195-1605 © Leslie Hempson 2018 DEDICATION To my parents, whose love and support has accompanied me every step of the way ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF ACRONYMS v GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS vi ABSTRACT vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE AGRO-INDUSTRIAL DIVIDE 23 CHAPTER 2: ACCOUNTING FOR BUSINESS 53 CHAPTER 3: WRITING THE ECONOMY 89 CHAPTER 4: SPINNING EMPLOYMENT 130 CONCLUSION 179 APPENDIX: WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 183 BIBLIOGRAPHY 184 iii LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 2.1 Advertisement for a list of businesses certified by AISA 59 3.1 A set of scales with coins used as weights 117 4.1 The ambar charkha in three-part form 146 4.2 Illustration from a KVIC album showing Mother India cradling the ambar 150 charkha 4.3 Illustration from a KVIC album showing giant hand cradling the ambar charkha 151 4.4 Illustration from a KVIC album showing the ambar charkha on a pedestal with 152 a modified version of the motto of the Indian republic on the front 4.5 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing the charkha to Mohenjo Daro 158 4.6 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing -

GUJARAT UNIVERSITY Hisotry M.A

Publication Department, Guajrat University [1] GUJARAT UNIVERSITY Hisotry M.A. Part-I Group - 'A' In Force from June 2003, Compulsory Paper-I (Historiography, Concept, Methods and Tools) (100 Marks : 80 Lectures) Unit-1 : Meaning and Scope of Hisotry (a) Meaning of History and Importance of its study. (b) Nature and Scope of History (c) Collection and selection of sources (data); evidence and its transmission; causation; and 'Historicism' Unit-2 : History and allied Disciplines (a) Archaeology; Geography; Numasmatics; Economics; Political Science; Sociology and Literature. Unit-3 : Traditions of Historical Writing (a) Greco-Roman traditions (b) Ancient Indian tradition. (c) Medieval Historiography. (d) Oxford, Romantic and Prussion schools of Historiography Unit-4 : Major Theories of Hisotry (a) Cyclical, Theological, Imperalist, Nationalist, and Marxist Unit-5 : Approaches to Historiagraphy (a) Evaluation of the contribution to Historiography of Ranke and Toynbee. (b) Assessment of the contribution to Indian Historiography of Jadunath Sarkar, G.S. Sardesai and R.C. Majumdar, D.D. Kosambi. (c) Contribution to regional Historiography of Bhagvanlal Indraji and Shri Durga Shankar Shastri. Paper-I Historiography, Concept, Methods and Tools. Suggested Readings : 1. Ashley Montagu : Toynbee and History, 1956. 2. Barnes H.E. : History of Historical Writing, 1937, 1963 3. Burg J.B. : The Ancient Greek Historians, 1909. 4. Car E.H. : What is History, 1962. 5. Cohen : The meaning of Human History, 1947, 1961. 6. Collingwood R.G. : The Idea of History, 1946. 7. Donagan Alan and Donagan Barbara : Philosophy of History, 1965 8. Dray Will Iam H : Philosophy of History, 1964. 9. Finberg H.P.R. (Ed.) : Approaches to History, 1962. -

Sardar Patel's Role in Nagpur Flag Satyagraha

Sardar Patel’s Role in Nagpur Flag Satyagraha Dr. Archana R. Bansod Assistant Professor & Director I/c (Centre for Studies & Research on Life & Works of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel (CERLIP) Vallabh Vidya Nagar, Anand, Gujarat. Abstract. In March 1923, when the Congress Working Committee was to meet at Jabalpur, the Sardar Patel is one of the most foremost figures in the Municipality passed a resolution similar to the annals of the Indian national movement. Due to his earlier one-to hoist the national flag over the Town versatile personality he made many fold contribution to Hall. It was disallowed by the District Magistrate. the national causes during the struggle for freedom. The Not only did he prohibit the flying of the national great achievement of Vallabhbhai Patel is his successful flag, but also the holding of a public meeting in completion of various satyagraha movements, particularly the Satyagraha at Kheda which made him a front of the Town Hall. This provoked the th popular leader among the people and at Bardoli which launching of an agitation on March 18 . The earned him the coveted title of “Sardar” and him an idol National flag was hoisted by the Congress for subsequent movements and developments in the members of the Jabalpur Municipality. The District Indian National struggle. Magistrate ordered the flag to be pulled down. The police exhibited their overzealousness by trampling Flag Satyagraha was held at Nagput in 1923. It was the the national flag under their feet. The insult to the peaceful civil disobedience that focused on exercising the flag sparked off an agitation. -

Chap 2 PF.Indd

Credit: Shankar I ts chptr… The challenge of nation-building, covered in the last chapter, was This famous sketch accompanied by the challenge of instituting democratic politics. Thus, by Shankar appeared electoral competition among political parties began immediately after on the cover of his collection Don’t Spare Independence. In this chapter, we look at the first decade of electoral Me, Shankar. The politics in order to understand original sketch was • the establishment of a system of free and fair elections; drawn in the context of India’s China policy. But • the domination of the Congress party in the years immediately this cartoon captures after Independence; and the dual role of the Congress during the era • the emergence of opposition parties and their policies. of one-party dominance. 2021–22 chapter 2 era of one-party dominance Challenge of building democracy You now have an idea of the difficult circumstances in which independent India was born. You have read about the serious challenge of nation-building that confronted the country right in the beginning. Faced with such serious challenges, leaders in many other countries of the world decided that their country could not afford to have democracy. They said that national unity was their first priority and that democracy will introduce differences and conflicts. In India,…. Therefore many of the countries that gained freedom from colonialism …hero-worship, plays a part “ experienced non-democratic rule. It took various forms: nominal in its politics unequalled democracy but effective control by one leader, one party rule or direct in magnitude by the part army rule. -

UNIT 1 UNITY and DIVERSITY Unity and Diversity

UNIT 1 UNITY AND DIVERSITY Unity and Diversity Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Concepts of Unity and Diversity 1.2.1 Meaning of Diversity 1.2.2 Meaning of Unity 1.3 Forms of Diversity in India 1.3.1 Racial Diversity 1.3.2 Linguistic Diversity 1.3.3 Religious Diversity 1.3.4 Caste Diversity 1.4 Bonds of Unity in India 1.4.1 Geo-political Unity 1.4.2 The Institution of Pilgrimage 1.4.3 Tradition of Accommodation 1.4.4 Tradition of Interdependence 1.5 Let Us Sum Up 1.6 Keywords 1.7 Further Reading 1.8 Specimen Answers to Check Your Progress 1.0 OBJECTIVES After studying this unit you should be able to z explain the concept of unity and diversity z describe the forms and bases of diversity in India z examine the bonds and mechanisms of unity in India z provide an explanation to our option for a composite culture model rather than a uniformity model of unity. 1.1 INTRODUCTION This unit deals with unity and diversity in India. You may have heard a lot about unity and diversity in India. But do you know what exactly it means? Here we will explain to you the meaning and content of this phrase. For this purpose the unit has been divided into three sections. In the first section, we will specify the meaning of the two terms, diversity and unity. 9 Social Structure Rural In the second section, we will illustrate the forms of diversity in Indian society. -

The Tyabji Clan—Urdu As a Symbol of Group Identity by Maren Karlitzky University of Rome “La Sapienza”

The Tyabji Clan—Urdu as a Symbol of Group Identity by Maren Karlitzky University of Rome “La Sapienza” T complex issue of group identity and language on the Indian sub- continent has been widely discussed by historians and sociologists. In particular, Paul Brass has analyzed the political and social role of language in his study of the objective and subjective criteria that have led ethnic groups, first, to perceive themselves as distinguished from one another and, subsequently, to demand separate political rights.1 Following Karl Deutsch, Brass has underlined that the existence of a common language has to be considered a fundamental token of social communication and, with this, of social interaction and cohesion. 2 The element of a “national language” has also been a central argument in European theories of nationhood right from the emergence of the concept in the nineteenth century. This approach has been applied by the English-educated élites of India to the reality of the Subcontinent and is one of the premises of political struggles like the Hindi-Urdu controversy or the political claims put forward by the Muslim League in promoting the two-nations theory. However, in Indian society, prior to the socio-political changes that took place during the nineteenth century, common linguistic codes were 1Paul R. Brass has studied the politics of language in the cases of the Maithili movement in north Bihar, of Urdu and the Muslim minority in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, and of Panjabi in the Hindu-Sikh conflict in Punjab. Language, Religion and Politics in North India (London: Cambridge University Press, ). -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information

The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LIX NO. 1 MARCH 2013 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. 24, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi-2 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor : T.K. Viswanathan Secretary-General Lok Sabha Associate Editors : P.K. Misra Joint Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Kalpana Sharma Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Assistant Editors : Pulin B. Bhutia Additional Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Parama Chatterjee Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Sanjeev Sachdeva Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat © Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOLUME LIX NO. 1 MARCH 2013 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL NOTE 1 ADDRESSES Addresses at the Inaugural Function of the Seventh Meeting of Women Speakers of Parliament on Gender-Sensitive Parliaments, Central Hall, 3 October 2012 3 ARTICLE 14th Vice-Presidential Election 2012: An Experience— T.K. Viswanathan 12 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES Conferences and Symposia 17 Birth Anniversaries of National Leaders 22 Exchange of Parliamentary Delegations 26 Bureau of Parliamentary Studies and Training 28 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 30 PRIVILEGE ISSUES 43 PROCEDURAL MATTERS 45 DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 49 SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha 62 Rajya Sabha 75 State Legislatures 83 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 85 APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Twelfth Session of the Fifteenth Lok Sabha 91 (iv) iv The Journal of Parliamentary Information II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 227th Session of the Rajya Sabha 94 III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2012 98 IV.