Oral History Interview with Carlos Villa, 1995 June 20-July 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The San Francisco Arts Quarterly SA Free Publication Dedicated to the Artistic Communityfaq

i 2 The San Francisco Arts Quarterly SA Free Publication Dedicated to the Artistic CommunityFAQ SOMA ISSUE: July.August.September Bay Area Arts Calendar The SOMA: Blue Collar to Blue Chip Rudolf Frieling from SFMOMA Baer Ridgway Gallery 111 Minna Gallery East Bay Focus: Johansson Projects free Artspan In Memory of Jim Marshall CONTENTS July. August. September 2010 Issue 2 JULY LISTINGS 5-28 111 Minna Gallery 75-76 Jay Howell AUGUST LISTINGS 29-45 Baer Ridgway Gallery 77-80 SEPTEMBER LISTINGS 47-60 Eli Ridgeway History of SOMA 63-64 Artspan 81-82 Blue Collar to Blue-Chip Heather Villyard Ira Nowinsky My Love for You is 83-84 SFMOMA 65-68 a Stampede of Horses New Media Curator Meighan O’Toole Rudolf Frieling The Seeker 85 Stark Guide 69 SF Music Collector Column Museum of Craft 86 Crown Point Press 70 and Folk Art Zine Review 71 East Bay Focus: 87-88 Johansson Projects The Contemporary 73 Jewish Museum In Memory: 89-92 Jim Marshall Zeum: 74 Children Museum Residency Listings 93-94 Space Resource Listings 95-100 FOUNDERS / EDITORS IN CHIEF Gregory Ito and Andrew McClintock MARKETING / ADVERTISING CONTRIBUTORS LISTINGS Andrew McClintock Contributing Writers Listing Coordinator [email protected] Gabe Scott, Jesse Pollock, Gregory Ito Gregory Ito Leigh Cooper, John McDermott, Assistant Listings Coordinator [email protected] Tyson Vogel, Cameron Kelly, Susan Wu Stella Lochman, Kent Long Film Listings ART / DESIGN Michelle Broder Van Dyke, Stella Lochman, Zmira Zilkha Gregory Ito, Ray McClure, Marianna Stark, Zmira Zilkha Residency Listings Andrew McClintock, Leigh Cooper Cameron Kelly Contributing Photographers Editoral Interns Jesse Pollock, Terry Heffernan, Special Thanks Susie Sherpa Michael Creedon, Dayna Rochell Tina Conway, Bette Okeya, Royce STAFF Ito, Sarah Edwards, Chris Bratton, Writers ADVISORS All our friends and peers, sorry we Gregory Ito, Andrew McClintock Marianna Stark, Tyson Vo- can’t list you all.. -

Tom Betthauser

TOM BETTHAUSER b. San Francisco 1987 CONTACT: [email protected] EDUCATION: Yale University, School of Art — MFA, Painting / Drawing 2012 San Francisco Art Institute — BFA, Painting / Drawing 2010 TEACHING / EMPLOYMENT EXPERIENCE: College of Marin, CA – Adjunct Professor, Beginning & Advanced Painting, May 2018 – Present San Francisco Art Institute, CA – Public Education Instructor, Jan 2018 – Present West Valley College, San Jose CA – Adjunct Professor, Studio Art / Art History, 2017 – Present University of California San Diego CA – Visiting Artist (lecture / studio visits) – Nov 2017 Wylie & May Louise Jones Gallery, Bakersfield CA – Chief Gallery Director / Curator, 2014 – 2017 Bakersfield College, CA – Adjunct Professor, Studio Art / Art History, 2014 – 2017 Cerro Coso Community College, CA – Adjunct Prof. Studio Art / Art History, 2013 – 2017 Natural History Museum of Los Angeles – Exhibit Technician (Seasonal) 2015 – 2016 Artvoices Magazine, Los Angeles CA – Contributing Writer, 2014 – 2016 Yale School of Art, New Haven CT – Teaching Assistant to Samuel Messer, 2011 – 2012 Yale School of Art, New Haven CT – Chief Graduate Admissions Coordinator, 2011 – 2012 Yale School of Art, New Haven CT – Art Handler / Installation Assistant, 2011 – 2012 San Francisco Art Institute, CA –Teaching Assistant / Academic Tutor, 2007 – 2010 Exploratorium Museum, CA – Explainer / Tactile Dome / Public Programs, 2006 – 2012 SELECTED GROUP / SOLO EXHIBITIONS: 2015 – PRESENT Crocker Museum of Art, CA – Big Names Small Art Benefit Auction – May -

Amanda Marchand

AMANDA MARCHAND EDUCATION: 2000 M.F.A., photography, San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, C.A 1992 Multi-media studies, Emily Carr College of Art & Design, Vancouver, B.C. 1990 B.A., Queen’s University, Kingston, O.N. SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS: 2015 Night Garden, Traywick Contemporary, Berkeley, CA 2012 Night Garden: The Summer Project, http://amandamarchand.com/blog/ 2005 The Density of Air, Bolinas Art Museum, Bolinas, CA 2004 415/514. San Francisco City Hall, Arts Commission Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2003 Amanda Marchand & Dennis McLeod. Traywick Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2002 You Came So Close. The Project Space, Headlands Center for the Arts, Marin, CA 2001 Under his Knowledge, Gallery Petite L.G., Houston, TX SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS: 2015 Front Yard/Backstreet, Palo Alto Art Center, Palo Alto, CA Center Forward, The Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins, CO Curve, CENTER, Santa Fe, NM Mind-scape, (exhibition and book launch), Datz Museum, Seoul, Korea 2012 Materials + Process, Traywick Contemporary, Berkeley, CA 2011 Tomorrow’s Stars: Verge Art Brooklyn, Dumbo, NY Manipulated, Castell Photography, Asheville, NC George Eastman House Panel (see below), Preview Show/Auction, The Metropolitain Pavillion, NY 2010 George Eastman House Preview Show and Auction, Sotheby’s, NY Love Pictures, curated by Will Mebane and Scott Tolmie. 2009 Group Show, Cavallo Point Lodge, Marin, CA. 2008 Arm’s Length in: Ceramics and the Treachery of Objects in the Digital Age. (Catalogue), Scripps College, 64th Annual, Claremont, CA. (collaboration with Jeanne Quinn) 2005 Photo New York. SFAI, Metropolitan Pavilion, New York, NY. Photo-Based. Traywick Contemporary, Berkeley, CA. -

Fall 201720172017

2017 2017 2017 2017 Fall Fall Fall Fall This content downloaded from 024.136.113.202 on December 13, 2017 10:53:41 AM All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c). American Art SummerFall 2017 2017 • 31/3 • 31/2 University of Chicago Press $20 $20 $20 $20 USA USA USA USA 1073-9300(201723)31:3;1-T 1073-9300(201723)31:3;1-T 1073-9300(201723)31:3;1-T 1073-9300(201723)31:3;1-T reform reform reform reform cameras cameras cameras cameras “prints” “prints” “prints” “prints” and and and and memory memory memory memory playground playground playground playground of of of Kent’s of Kent’s Kent’s Kent’s guns, guns, guns, guns, abolitionism abolitionism abolitionism abolitionism art art art art and and and and the the the the Rockwell literary Rockwell Rockwell literary literary Rockwell issue literary issue issue issue Group, and Group, and Group, and Group, and in in in in this this this this Homer—dogs, Homer—dogs, Homer—dogs, Place Homer—dogs, Place Place Place In In In In nostalgia Park nostalgia nostalgia Park Park nostalgia Park Duncanson’s Duncanson’s Duncanson’s Duncanson’s Christenberry the Christenberry S. Christenberry the S. the S. Christenberry the S. Winslow Winslow Winslow Winslow with with with with Robert Robert Robert Robert Suvero, Suvero, Suvero, Suvero, William William William William di di di Technological di Technological Technological Technological Hunting Hunting Hunting Hunting Mark Mark Mark Mark Kinetics of Liberation in Mark di Suvero’s Play Sculpture Melissa Ragain Let’s begin with a typical comparison of a wood construction by Mark di Suvero with one of Tony Smith’s solitary cubes (fgs. -

Leo Valledor: Interview About the Artist with Professor Carlos Villa of San Francisco Art Instititute

Leo Valledor: Interview about the artist with Professor Carlos Villa of San Francisco Art Instititute CV: Carlos Villa MB: Maria Bonn CV: I think that he is probably super important. He is super important because at the time there were maybe five or six artists, all of whom came from the Philippines, that set the foundation for Pilipino‐American art history for instance. But the first practitioner, or the first participant, in the art world who was born here was my cousin Leo Valedor. And Leo Valedor was an artist who came here to California School of Fine Arts on a scholarship directly from high school. He was about 18 at the time and he excelled so much in what he did. He stood beyond most of the people here at school that were just at his stage and he was recognized by a lot of the people who started the Six Gallery. The people who started the Six Gallery were all members of studio 15. Studio 15 was one of the studios, it’s an honors studio now, but before that it was a studio in which Joan Brown, Hayward King, all of these people and Wally Hedrick… MB: Here? CV: Yeah, here at the school. And it was a hot bed. All of these people were students at the school. They were the people beyond the great teachers and they went out and started the Six Gallery. Well, they saw Leo’s work and they said you are coming into Studio 15. So being in Studio 15 was incredibly honorific and he was the youngest kid there. -

D-L Alvarez B

! D-L Alvarez b. 1966 Lives and works in Berlin, Germany Solo Exhibitions 2015 The Children’s Hour, [2nd Floor Projects], San Francisco, CA 2014 D-L Alvarez and Eileen Maxson, Artadia Gallery, New York, NY 2013 The Unforgiving Minute, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2012 D-L Alvarez: MATRIX 243, Berkley Art Museum, Berkley, CA 2011 Galeria Casado Santapau, Madrid, Spain 2009 Dusty Hayes, 2nd Floor Projects, San Francisco, CA 2008 Dead Leafs, Galeria Casado Santapau, Madrid, Spain 2007 Parents' Day, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY DIG, with Wayne Smith, Derek Eller Gallery (project room), New York, NY 2006 Casper, (with Matthew Lutz-Kinoy), A +B Arratiabeer, Berlin, Germany, 2005 rise, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY Ice, Glue, Berlin, Germany 2004 Beausoleil, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2002 The Road to Hell Less Traveled, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2000 Sculpture Garden, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY ! ! 1999 Chorus, John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco, CA 1998 Knights Gathering Flowers, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY Dust, Th.e (Theoretical Events), Naples, Italy 1995 Dandylion, Jack Hanley Gallery, San Francisco, CA A Shepherd and His Flock, London Projects, London, UK 1994 Night of the Hunter, Kiki, San Francisco, CA 1990 Political Stance, (installation documenting performance), ATA, San Francisco, CA 1989 Elvis Clocked, Les Indes Galantes, Paris, France Group Exhibitions 2017 Drawings from the Collection: 1980 to Today, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA 2016 Subject To Capital, Henry -

The Quintessence of Ibsenism

2012-11-24 21:11:01 UTC 50acf1ea2c121 89.181.149.9 Portugal THE QUINTESSENCE OF IBSENISM: BY G. BERNARD SHAW. LONDON: WALTER SCOTT 24 WARWICK LANE. 1891 CONTENTiS. PREFACE. Society, IN the spring of 1890, the Fabian finding itself at a loss for a course of lectures to occupy its summer meetings, was pelledcom- to make shift with a series of papers put " forward under the general heading Socialism in Contemporary Literature." The Fabian " Essayists, strongly pressed to do something or other," for the most part shook their heads ; but " in the end Sydney Olivier consented to take Zola"; I consented to "take Ibsen"; and Hubert Bland undertook to read all the Socialist novels of the day, an enterprise the desperate failure of which resulted in the most amusing paper of the series. William Morris, asked to read a paper on himself, flatly declined, but gave us one on Gothic Architecture. Stepniak also came to the rescue with a lecture on modern Russian fiction ; and so the Society tided over the summer without having to close its doors, but also without having added anything what- vi Preface. ever to the general stock of information on Socialism in Contemporary Literature. After this I cannot claim that my paper on Ibsen, which was duly read at the St James's Restaurant on the 1 8th July 1890, under the presidency of Mrs Annie Besant, and which was the first form of this little book, is an original work in the sense of being the result of a spontaneous ternalin- impulse on my part. -

San Francisco 9

300 ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd See also separate subindexes for: 5 EATING P304 6 DRINKING & NIGHTLIFE P306 3 ENTERTAINMENT P307 7 SHOPPING P307 2 SPORTS & ACTIVITIES P308 Index 4 SLEEPING P309 16th Ave Steps 137 A iDS (Acquired immune Bay Area Rapid Transit, see California Historical Society 22nd St Hill 175 Deficiency Syndrome) BART Museum 86 49 Geary 83 264 Bay Bridge 13, 80, 284, 17 Calistoga 231 77 Geary 83 air travel 286-7 Bay Model Visitor Center car travel 286, 289-90 826 Valencia 151 Alamo Square Park 186, 190 (Sausalito) 224 Carnaval 21, 157 1906 Great Quake & Fire Alcatraz 9, 52-5, 8, 52 Bay to Breakers 21, 23 Cartoon Art Museum 85-6 283-4 alleyways 20 beaches 20, 61, 206 Casa Nuestra (St Helena) 1989 Loma Prieta Quake 284 ambulances 293 Beat movement 118, 119, 229 Amtrak 287 122, 131, 262 Castello di Amorosa Angel island 228 Beat Museum 118 (Calistoga) 229-30 A animals 19-20, 24 beer 30, 32, 270 Castro, the 49, 173-82, accommodations 336 Belden Place 93 239-52, see also AP Hotaling Warehouse 82 accommodations 241, 251 Sleeping subindex Aquarium of the Bay 58 Benziger (Glen Ellen) 236 drinking & nightlife 174, Avenues, the 252 Aquatic Park 57 Berkeley 217-20, 218 177, 180-1 Castro, the 251 architecture 19, 191, 279-82, Bernal Heights 171 entertainment 181 Chinatown 248-9 5, 190-1 bicycling 41, 74, 87, 113, 214, food 174, 176-7 Civic Center & the area codes 296 232, 238, 291 highlights 173-4 Tenderloin 243-7 arts 273-5 bike-share program 291 shopping 174, 181-2 Downtown 243-7 Asian Art Museum 81 bisexual travelers 36-7 -

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2017/2018

ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR 2017/2018 1 MISSION San Francisco Art Institute is dedicated to the intrinsic value of art and its vital role in shaping and enriching society and Left: the individual. As a diverse community Installation view of the BFA Exhibition, of working artists and scholars, SFAI Diego Rivera Gallery, 2018. provides its students with a rigorous Photo by Alex education in the fine arts and preparation Peterson (BFA Photography, 2015). for a life in the arts through an immersive studio environment, an integrated liberal Below: Rigo 23, One Tree arts curriculum, and critical engagement mural. Photo by with the world. Trevor Hacker. Spread:2 Performance by Tim Sullivan’s New Genres class on the rooftop amphitheatre at SFAI—Chestnut Street Campus. CONTENTS 4 FROM THE PRESIDENT 5 FROM THE BOARD CHAIR 6 HISTORY A Brief History of SFAI Firsts + Foremosts 10 NOTABLE ALUMNI 11 FACILITIES Chestnut Street Campus Fort Mason Campus Residence Halls 15 DEGREE PROGRAMS 16 NAMED SCHOLARSHIPS 18 FINANCIALS 19 EXHIBITIONS + PUBLIC PROGRAMS Galleries/Exhibition Spaces Visiting Artists + Scholars Lecture Series Public + Youth Education 22 ANNUAL GIFTS Vernissage 2018 Top to bottom: Students in the fountain at SFAI's Chestnut Street Campus, circa 1972. Photo by Richard Laughlin (MFA 1973). Work by Ahna Fender (BFA Painting) in the SFAI Courtyard. 3 SFAI President Gordon Knox at SFAI's Fort Mason Campus. Photo by Duy Ho. And this is a hard job, since the work of arts education is interwoven with the realities of economic systems, social inequality and political volatility. As SFAI builds on our recent progress, we must ensure that students as well as the institution itself emerge nimble, adaptable and resilient in the face of rapid change. -

Light Horses : Breeds and Management

' K>\.K>. > . .'.>.-\ j . ; .>.>.-.>>. ' UiV , >V>V >'>>>'; ) ''. , / 4 '''. 5 : , J - . ,>,',> 1 , .\ '.>^ .\ vV'.\ '>»>!> ;;••!>>>: .>. >. v-\':-\>. >*>*>. , > > > > , > > > > > > , >' > > >»» > >V> > >'» > > > > > > . »v>v - . : . 9 '< TUFTS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES 3 9090 014 661 80 r Family Libra;-, c veterinary Medium f)HBnf"y Schoo Ve' narv Medicine^ Tu iiv 200 Wesuc . ,-<oao Nerth Graft™ MA 01538 kXsf*i : LIVE STOCK HANDBOOKS. Edited by James Sinclair, Editor of "Live Stock Journal" "Agricultural Gazette" &c. No. II. LIGHT HORSES. BREEDS AND MANAGEMENT BY W. C. A. BLEW, M.A, ; WILLIAM SCARTH DIXON ; Dr. GEORGE FLEMING, C.B., F.R.C.V.S. ; VERO SHAW, B.A. ; ETC. SIZKZTJBI ZEiZDITIOILT, le-IEJ-VISIEID. ILLUSTRATED. XonDon VINTON & COMPANY, Ltd., 8, BREAM'S BUILDINGS, CHANCERY LANE, E.C. 1919. —— l°l LIVE STOCK HANDBOOKS SERIES. THE STOCKBREEDER'S LIBRARY. Demy 8vo, 5s. net each, by post, 5s. 6d., or the set of five vols., if ordered direct from the Publisher, carriage free, 25s. net; Foreign 27s. 6d. This series covers the whole field of our British varieties of Horses, Cattle, Sheep and Pigs, and forms a thoroughly practical guide to the Breeds and Management. Each volume is complete in itself, and can be ordered separately. I. —SHEEP: Breeds and Management. New and revised 8th Edition. 48 Illustrations. By John Wrightson, M.R.A.C., F.C.S., President of the College of Agriculture, Downton. Contents. —Effects of Domestication—Long and Fine-woolled Sheep—British Long-woolled Sheep—Border Leicesters—Cotswolds—Middle-woolled—Mountain or Forest—Apparent Diff- erences in Breeds—Management—Lambing Time— Ordinary and Extraordinary Treatment of Lambs—Single and Twin Lambs—Winter Feeding—Exhibition Sheep—Future of Sheep Farm- ing—A Large Flock—Diseases. -

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

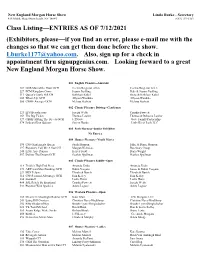

Class Listing—ENTRIES AS of 7/12/2021 (Exhibitors, Please—If You Find an Error, Please E-Mail Me with the Changes So That We Can Get Them Done Before the Show

New England Morgan Horse Show Linda Burke - Secretary 435 Middle Road Horseheads, NY 14845 (607) 739-6169 Class Listing—ENTRIES AS OF 7/12/2021 (Exhibitors, please—if you find an error, please e-mail me with the changes so that we can get them done before the show. [email protected]. Also, sign up for a check in appointment thru signupgenius.com. Looking forward to a great New England Morgan Horse Show. 001 English Pleasure--Amateur 102 GLB Man of the Hour GCH Cecilia Bergeron Allen Cecilia Bergeron Allen 227 FCM Kingdom Come Jeanne Fuelling Dale & Jeanne Fuelling 311 Queen's Castle Hill CH Kathleen Kabel Steve & Kathleen Kabel 380 What's Up GCH Allyson Wandtke Allyson Wandtke 566 CBMF Avenger GCH Melissa Beckett Melissa Beckett 002 Classic Pleasure Driving--Gentlemen 123 LPS Beaudacious Joseph Webb Cynthia Fawcett 169 The Big Ticket Thomas Lawlor Thomas & Rebecca Lawlor 327 CBMF Hitting The Streets GCH Jeff Gove Gove Family Partnership 574 Ledyard Don Quixote Steven Handy Little Bit of Luck LLC 003 Park Harness--Junior Exhibitor No Entries 004 Hunter Pleasure--Youth Mares 190 CFS Gentlemen's Queen Sarah Munson Mike & Diane Munson 197 Playmor's Call Me A Star CH Morgan Nicholas Rosemary Croop 248 Little Acre Dancia Kelsey Scott Darla Wright 507 Deliver The Dream GCH Scarlett Spellman Scarlett Spellman 005 Classic Pleasure Saddle--Open 118 Treble's High End Piece Amanda Zsido Amanda Zsido 173 ADC Last Man Standing GCH Robin Vergato James & Robin Vergato 229 MJS Eclipse Elizabeth Burick Elizabeth Burick 314 CFF Personal Advantage GCH