ON the WATERFRONT Promotor: Ir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shiva's Waterfront Temples

Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Subhashini Kaligotla All rights reserved ABSTRACT Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla This dissertation examines Deccan India’s earliest surviving stone constructions, which were founded during the 6th through the 8th centuries and are known for their unparalleled formal eclecticism. Whereas past scholarship explains their heterogeneous formal character as an organic outcome of the Deccan’s “borderland” location between north India and south India, my study challenges the very conceptualization of the Deccan temple within a binary taxonomy that recognizes only northern and southern temple types. Rejecting the passivity implied by the borderland metaphor, I emphasize the role of human agents—particularly architects and makers—in establishing a dialectic between the north Indian and the south Indian architectural systems in the Deccan’s built worlds and built spaces. Secondly, by adopting the Deccan temple cluster as an analytical category in its own right, the present work contributes to the still developing field of landscape studies of the premodern Deccan. I read traditional art-historical evidence—the built environment, sculpture, and stone and copperplate inscriptions—alongside discursive treatments of landscape cultures and phenomenological and experiential perspectives. As a result, I am able to present hitherto unexamined aspects of the cluster’s spatial arrangement: the interrelationships between structures and the ways those relationships influence ritual and processional movements, as well as the symbolic, locative, and organizing role played by water bodies. -

TOURISM INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENTS Leveraging Partnerships for Exponential Growth

TOURISM INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENTS Leveraging Partnerships for Exponential Growth THEME PARKS CRUISE INFRASTRUCTURE HEALTHCARE WELLNESS ADVENTURE MICE MEDICAL TITLE Tourism Infrastructure Investments: Leveraging Partnerships for Exponential Growth YEAR July, 2018 AUTHORS STRATEGIC GOVERNMENT ADVISORY (SGA), YES Global Institute, YES BANK No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form by photo, photoprint, microfilm or any COPYRIGHT other means without the written permission of YES BANK Ltd. & FICCI. This report is the publication of YES BANK Limited (“YES BANK”) & FICCI and so YES BANK & FICCI have editorial control over the content, including opinions, advice, Statements, services, offers etc. that is represented in this report. However, YES BANK & FICCI will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by the reader’s reliance on information obtained through this report. This report may contain third party contents and third-party resources. YES BANK & FICCI take no responsibility for third party content, advertisements or third party applications that are printed on or through this report, nor does it take any responsibility for the goods or services provided by its advertisers or for any error, omission, deletion, defect, theft or destruction or unauthorized access to, or alteration of, any user communication. Further, YES BANK & FICCI do not assume any responsibility or liability for any loss or damage, including personal injury or death, resulting from use of this report or from any content for communications or materials available on this report. The contents are provided for your reference only. The reader/ buyer understands that except for the information, products and services clearly identified as being supplied by YES BANK & FICCI, it does not operate, control or endorse any information, products, or services appearing in the report in any way. -

Integrated State Water Plan for Lower Bhima Sub Basin (K-6) of Krishna Basin

Maharashtra Krishna Valley Development Corporation Pune. Chief Engineer (S.P) W.R.D Pune. Integrated state water Plan for Lower Bhima Sub basin (K-6) of Krishna Basin Osmanabad Irrigation Circle, Osmanabad K6 Lower Bhima Index INDEX CHAPTER PAGE NO. NAME OF CHAPTER NO. 1.0 INTRODUCTION 0 1.1 Need and principles of integrated state water plan. 1 1.2 Objectives of a state water plan for a basin. 1 1.3 Objectives of the maharashtra state water policy. 1 1.4 State water plan. 1 1.5 Details of Catchment area of Krishna basin. 2 1.6 krishna basin in maharashtra 2 1.7 Location of lower Bhima sub basin (K-6). 2 1.8 Rainfall variation in lower Bhima sub basin. 2 1.9 Catchment area of sub basin. 3 1.10 District wise area of lower Bhima sub basin. 3 1.11 Topographical descriptions. 5 1.11 Flora and Fauna in the sub basin. 6 2.0 RIVER SYSTEM 2.1 Introduction 11 2.2 Status of Rivers & Tributaries. 11 2.3 Topographical Description. 11 2.4 Status of Prominent Features. 12 2.5 Geomorphology. 12 2.6 A flow chart showing the major tributaries in the sub basin. 13 3.0 GEOLOGY AND SOILS 3.1 Geology. 16 3.1.1 Introduction. 16 3.1.2 Drainage. 16 3.1.3 Geology. 16 3.1.4 Details of geological formation. 17 K6 Lower Bhima Index 3.2 Soils 18 3.2.1 Introduction. 18 3.2.2 Land capability Classification of Lower Bhima Sub Basin (K6). -

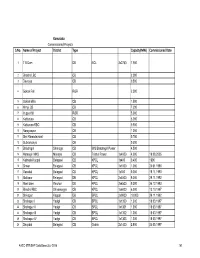

Karnataka Commissioned Projects S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date

Karnataka Commissioned Projects S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date 1 T B Dam DB NCL 3x2750 7.950 2 Bhadra LBC CB 2.000 3 Devraya CB 0.500 4 Gokak Fall ROR 2.500 5 Gokak Mills CB 1.500 6 Himpi CB CB 7.200 7 Iruppu fall ROR 5.000 8 Kattepura CB 5.000 9 Kattepura RBC CB 0.500 10 Narayanpur CB 1.200 11 Shri Ramadevaral CB 0.750 12 Subramanya CB 0.500 13 Bhadragiri Shimoga CB M/S Bhadragiri Power 4.500 14 Hemagiri MHS Mandya CB Trishul Power 1x4000 4.000 19.08.2005 15 Kalmala-Koppal Belagavi CB KPCL 1x400 0.400 1990 16 Sirwar Belagavi CB KPCL 1x1000 1.000 24.01.1990 17 Ganekal Belagavi CB KPCL 1x350 0.350 19.11.1993 18 Mallapur Belagavi DB KPCL 2x4500 9.000 29.11.1992 19 Mani dam Raichur DB KPCL 2x4500 9.000 24.12.1993 20 Bhadra RBC Shivamogga CB KPCL 1x6000 6.000 13.10.1997 21 Shivapur Koppal DB BPCL 2x9000 18.000 29.11.1992 22 Shahapur I Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1300 1.300 18.03.1997 23 Shahapur II Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1301 1.300 18.03.1997 24 Shahapur III Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1302 1.300 18.03.1997 25 Shahapur IV Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1303 1.300 18.03.1997 26 Dhupdal Belagavi CB Gokak 2x1400 2.800 04.05.1997 AHEC-IITR/SHP Data Base/July 2016 141 S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date 27 Anwari Shivamogga CB Dandeli Steel 2x750 1.500 04.05.1997 28 Chunchankatte Mysore ROR Graphite India 2x9000 18.000 13.10.1997 Karnataka State 29 Elaneer ROR Council for Science and 1x200 0.200 01.01.2005 Technology 30 Attihalla Mandya CB Yuken 1x350 0.350 03.07.1998 31 Shiva Mandya CB Cauvery 1x3000 3.000 10.09.1998 -

Tungabhadra Dam

Tungabhadra Dam drishtiias.com/printpdf/tungabhadra-dam Why in News Recently, the Vice President visited the Tungabhadra dam in Karnataka. Key Point About: Tungabhadra dam also known as Pampa Sagar is a multipurpose dam built across Tungabhadra River in Hosapete, Ballari district of Karnataka. It was built by Dr. Thirumalai Iyengar in 1953. Tungabhadra reservoir has a storage capacity of 101 TMC (Thousand Million Cubic feet) with catchment area spreading to 28000 square kms. It is about 49.5 meters in height. Importance: It is the life-line of 6 chronically drought prone districts of Bellary, Koppal and Raichur in Karnataka (popularly known as the rice bowl of Karnataka) and Anantapur, Cuddapah and Kurnool in neighbouring Andhra Pradesh. Besides irrigating vast patches of land in the two states, it also generates hydel power and helps prevent floods. 1/2 Tungabhadra River It is a sacred river in southern India that flows through the state of Karnataka to Andhra Pradesh. The ancient name of the river was Pampa. The river is approximately 710 km long, and it drains an area of 72,200 sq km. It is formed by the confluence of two rivers, the Tunga River and the Bhadra River. Both Tunga & Bhadra Rivers originate on the eastern slopes of the Western Ghats. The greater part of the Tungabhadra’s course lies in the southern part of the Deccan plateau. The river is fed mainly by rain, and it has a monsoonal regimen with summer high water. It’s Major tributaries are the Bhadra, the Haridra, the Vedavati, the Tunga, the Varda and the Kumdavathi. -

Indian Tourism Infrastructure

INDIAN TOURISM INFRASTRUCTURE InvestmentINDIAN TOURISM INFRASTRUCTUREOppor -tunities Investment Opportunities & & Challenges Challenges 1 2 INDIAN TOURISM INFRASTRUCTURE - Investment Opportunities & Challenges Acknowledgement We extend our sincere gratitude to Shri Vinod Zutshi, Secretary (Former), Ministry of Tourism, Government of India for his contribution and support for preparing the report. INDIAN TOURISM INFRASTRUCTURE - Investment Opportunities & Challenges 3 4 INDIAN TOURISM INFRASTRUCTURE - Investment Opportunities & Challenges FOREWORD Travel and tourism, the largest service industry in India was worth US$234bn in 2018 – a 19% year- on-year increase – the third largest foreign exchange earner for India with a 17.9% growth in Foreign Exchange Earnings (in Rupee Terms) in March 2018 over March 2017. According to The World Travel and Tourism Council, tourism generated ₹16.91 lakh crore (US$240 billion) or 9.2% of India’s GDP in 2018 and supported 42.673 million jobs, 8.1% of its total employment. The sector is predicted to grow at an annual rate of 6.9% to ₹32.05 lakh crore (US$460 billion) by 2028 (9.9% of GDP). The Ministry has been actively working towards the development of quality tourism infrastructure at various tourist destinations and circuits in the States / Union Territories by sanctioning expenditure budgets across schemes like SWADESH DARSHAN and PRASHAD. The Ministry of Tourism has been actively promoting India as a 365 days tourist destination with the introduction of niche tourism products in the country like Cruise, Adventure, Medical, Wellness, Golf, Polo, MICE Tourism, Eco-tourism, Film Tourism, Sustainable Tourism, etc. to overcome ‘seasonality’ challenge in tourism. I am pleased to present the FICCI Knowledge Report “Indian Tourism Infrastructure : Investment Opportunities & Challenges” which highlights the current scenario, key facts and figures pertaining to the tourism sector in India. -

Dams of India.Cdr

eBook IMPORTANT DAMS OF INDIA List of state-wise important dams of India and their respective rivers List of Important Dams in India Volume 1(2017) Dams are an important part of the Static GK under the General Awareness section of Bank and Government exams. In the following eBook, we have provided a state-wise list of all the important Dams in India along with their respective rivers to help you with your Bank and Government exam preparation. Here’s a sample question: In which state is the Koyna Dam located? a. Gujarat b. Maharashtra c. Sikkim d. Himachal Pradesh Answer: B Learning the following eBook might just earn you a brownie point in your next Bank and Government exam. Banking & REGISTER FOR A Government Banking MBA Government Exam 2017 Free All India Test 2 oliveboard www.oliveboard.in List of Important Dams in India Volume 1(2017) LIST OF IMPORTANT DAMS IN INDIA Andhra Pradesh NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Nagarjuna Sagar Dam (also in Telangana) Krishna Somasila Dam Penna Srisailam Dam (also in Telangana) Krishna Arunachal Pradesh NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Ranganadi Dam Ranganadi Bihar NAME OF THE DAM 2 RIVER Nagi Dam Nagi Chhattisgarh NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Minimata (Hasdeo) Bango Dam Hasdeo Gujarat NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Kadana Dam Mahi Karjan Dam Karjan Sardar Sarover Dam Narmada Ukai Dam Tapi 3 oliveboard www.oliveboard.in List of Important Dams in India Volume 1(2017) Himachal Pradesh NAME OF THE DAM RIVER Bhakra Dam Sutlej Chamera I Dam Ravi Kishau Dam Tons Koldam Dam Sutlej Nathpa Jhakri Dam Sutlej Pong Dam Beas Jammu & Kashmir NAME -

6. Water Quality ------61 6.1 Surface Water Quality Observations ------61 6.2 Ground Water Quality Observations ------62 7

Version 2.0 Krishna Basin Preface Optimal management of water resources is the necessity of time in the wake of development and growing need of population of India. The National Water Policy of India (2002) recognizes that development and management of water resources need to be governed by national perspectives in order to develop and conserve the scarce water resources in an integrated and environmentally sound basis. The policy emphasizes the need for effective management of water resources by intensifying research efforts in use of remote sensing technology and developing an information system. In this reference a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed on December 3, 2008 between the Central Water Commission (CWC) and National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) to execute the project “Generation of Database and Implementation of Web enabled Water resources Information System in the Country” short named as India-WRIS WebGIS. India-WRIS WebGIS has been developed and is in public domain since December 2010 (www.india- wris.nrsc.gov.in). It provides a ‘Single Window solution’ for all water resources data and information in a standardized national GIS framework and allow users to search, access, visualize, understand and analyze comprehensive and contextual water resources data and information for planning, development and Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM). Basin is recognized as the ideal and practical unit of water resources management because it allows the holistic understanding of upstream-downstream hydrological interactions and solutions for management for all competing sectors of water demand. The practice of basin planning has developed due to the changing demands on river systems and the changing conditions of rivers by human interventions. -

Krishna Basin

CENTRAL WATER COMMISSION Krishna & Godavari Basin Organisation, Hyderabad Daily Bulletin for Flood Forecasting Stations Division : Lower Krishna Division Bulletin No : 22 Krishna Basin : . Dated : 6/22/2019 8:00 Inflow Forecast Stations : S.No Forecast Station Full Reservoir Level Live Capacity at FRL Level at 0800 Hours Live Storage on date % of Live Average Inflow Average Outflow Storage of last 24 hours of last 24 hours Vol. Diff. in Daily Rainfall & Estimated Discharge of all Base Stations at 08.30 Hours in Krishna Basin last 24 hrs (TMC) Estimated Metre Feet MCM TMC Metre Feet Trend MCM TMC Cumec Cusec Cumec Cusec Sl.No. Station River RF in mm Water Level (m) Discharge 1 Almatti Dam 519.60 1704.72 3137.18 110.78 508.01 1666.70 S 261.18 9.22 8 0 0 12 428 -0.04 (Cumec) 2 Narayanpur Dam 492.25 1614.99 740.35 26.14 487.18 1598.36 S 220.85 7.80 30 6 211 2 86 0.00 1 Kurundwad Krishna 4.9 522.535 No Flow 3 P D Jurala Project 318.52 1045.01 192.40 6.79 313.03 1027.00 S -59.61 -2.10 -31 0 14 3 95 -0.01 2 Sadalga Dudhganga 0.0 528.470 No Flow 4 Tungabhadra Dam 497.74 1633.01 2855.89 100.84 479.76 1574.03 S 58.86 2.08 2 0 0 5 189 -0.02 3 Gokak Ghataprabha 0.0 539.284 No Flow 5 Sunkesula Barrage 292.00 958.00 33.98 1.20 285.18 935.63 F 0.00 0.00 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 4 Almatti Dam Krishna 0.0 508.010 - 6 Srisailam Dam 269.75 885.01 6110.90 215.78 245.73 806.20 S 812.43 28.69 13 30 1049 0 0 -0.09 5 Cholachguda Malaprabha 0.0 524.750 No Flow 7 Pulichintala Proj. -

Probabilistic Predictions for Hydrology Applications

Probabilistic Predictions for Hydrology Applications S. C. Kar NCMRWF, Noida (Email: [email protected]) International Conference on Ensemble Methods in Modelling and Data Assimilation (EMMDA) 24-26 February 2020 Motivation TIGGE Datasets ANA and FCST for Nov 30 2017 TIGGE Datasets ANA and FCST for Dec 01 2017 Analysis and Forecasts of Winds at 925hPa MSLP Forecast and Analysis (Ensemble members) Uncertainties in Seasonal Simulations (CFS and GFS) Daily Variation of Ensemble Spread Surface hydrology exhibit significant interannual variability River Basins in India over this region due to interannual variations in the summer monsoon precipitation. The western and central Himalayas including the Hindukush mountain region receive large amount of snow during winter seasons during the passage of western disturbances. Snowmelt Modeling: GLDAS models Variation in Snowmelt among Hydrology Models is quite large Evaporation from GLDAS Models For proper estimation Evaporation, consistent forcing to hydrology model (especially precipitation, Soil moisture etc) and proper modeling approach is required. Extended-Range Probabilistic Predictions of Drought Occurrence 5-day accumulated rainfall forecasts (up to 20 days) have been considered. Ensemble spread (uncertainties in forecast) examined for each model IITM ERPS at 1degree 11 members T382GFS 11 members T382 CFS 11 members T126 GFS 11 members T126 CFS Probabilistic extended range forecasts were prepared considering all 44 members Probability that rainfall amount in next 5-days will be within 0-25mm -

List of Dams in India: State Wise

ambitiousbaba.com Online Test Series List of Dams in India: State Wise State DAM and Location Rajasthan • RanapratapSagar Dam(Chambal River), at Rawatbhata • Mahi Bajaj Sagar Dam (Mahi River) at Banswara district • Bisalpur Dam (Banas River), At Tonk district • Srisailam Dam(Krishna River), at Kurnool Andhra Pradesh district • Somasila Dam (Penna River), at Nellore district • Prakasam Barrage (Krishna River), at Krishna and Guntur • Tatipudi Reservoir(River Gosthani ), at Tatipudi, Vizianagaram • Gandipalem Reservoir (River Penner) • Ramagundam dam (Godavari), in Karimnagar • Dummaguden Dam (river Godavari) Telangana • Nagarjuna Sagar Dam (Krishna river), at Nagarjuna Sagar Nalgonda • Sri Ram Sagar (River Godavari) • Nizam Sagar Dam (Manjira River) • Dindi Reservoir (River Krishna), at Dindi, Mahabubnagar town • Lower Manair Dam (Manair River) • Singur Dam (river Manjira) Bihar • Kohira Dam (Kohira River), at Kaimur district • Nagi Dam (Nagi River), in Jamui District Chhattisgarh • HasdeoBango Dam (Hasdeo River), at Korba district Gujarat • SardarSarovar Dam(Narmada river), at Navagam • Ukai Dam(Tapti River), at Ukai in Tapi district IBPS | SBI | RBI | SEBI | SIDBI | NABARD | SSC CGL | SSC CHSL | AND OTHER GOVERNMENT EXAMS 1 ambitiousbaba.com Online Test Series • Kadana Dam( Mahi River), at Panchmahal district • Karjan Reservoir (Karjan river), at Jitgadh village of Nanded Taluka, Dist. Narmada Himachal Pradesh • Bhakra Dam (Sutlej River) in Bilaspur • The Pong Dam (Beas River ) • The Chamera Dam (River Ravi) at Chamba district J & K -

Answered On:21.08.2000 Clearance to Projects in Karnataka Rudragouda Patil

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:4352 ANSWERED ON:21.08.2000 CLEARANCE TO PROJECTS IN KARNATAKA RUDRAGOUDA PATIL Will the Minister of ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTS be pleased to state: (a) the number and details of the various projects sent to the Union Government by Karnataka for environmental clearance during the last three years; (b) whether Upper Krishna Project, Stage-I and II and Uduthorehalla Project have been given environmental clearance; and (c) if not, the reasons therefor and the time by which environmental clearance is likely to be accorded by the Union Government? Answer MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTS (SHRI BABU LAL MARANDI) (a) 25 projects were received during last three years from Karnataka for environmental clearance . A list is annexed. (b)&(c) Upper Krishna project Stage-I consists of Phase-I , Phase-II and Phase-IIIP. hase I was not referred to this Ministry for environmental clearance, Phase-II & Phase-III were accorded environmental clearance on 05.04.1989 and 18.07.2000 respectively. Stage-II project was considered by the Expert Committee for River Valley & Hydroelectric projects on 21.07.2000 for environmental clearance. Additional information sought from the project proponent has not been received. Decision on the proposal for environmental clearance will be taken within ninety(90) days of receipt of complete information. Uduthorehalla project has not been received for environmental clearance. ANNEXUREI N RESPECT OF PART(a)OF LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.4352 FOR 21.08.2000 REGARDING `CLEARANCE TO PROJECTS IN KARNATAKA `. S.No.