China's Changing Strategic Concerns: the Impact on Human

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Written Evidence Submitted by East Turkistan Government in Exile (XIN0078)

Written evidence submitted by East Turkistan Government in Exile (XIN0078) The East Turkistan Problem and How the UK Should Address it East Turkistan Government in Exile The East Turkistan Government in Exile (ETGE) is the democratically elected official body representing East Turkistan and its people. On September 14, 2004, the government in exile was established in Washington, DC by a coalition of Uyghur and other East Turkistani organizations. The East Turkistan Government in Exile is a democratic body with a representative Parliament. The primary leaders — President, Vice President, Prime Minister, Speaker (Chair) of Parliament, and Deputy Speaker (Chair) of Parliament — are democratically elected by the Parliament members from all over the East Turkistani diaspora in the General Assembly which takes place every four years. The East Turkistan Government in Exile is submitting this evidence and recommendation to the UK Parliament and the UK Government as it is the leading body representing the interests of not only Uyghurs but all peoples of East Turkistan including Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, and Tatars. More importantly, the ETGE has submitted the first ever legal complaint to the International Criminal Court against China and its officials for genocide and other crimes against humanity. We would like the UK Government to assist our community using all available means to seek justice and end to decades of prolonged colonization, genocide, and occupation in East Turkistan. Brief History of East Turkistan and the Uyghurs With a history of over 6000 years, according to Uyghur historians like Turghun Almas, the Uyghurs are the natives of East Turkistan. Throughout the millennia, the Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples have established and maintained numerous independent kingdoms, states, and even empires. -

Comprehensive Encirclement

COMPREHENSIVE ENCIRCLEMENT: THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY’S STRATEGY IN XINJIANG GARTH FALLON A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences International and Political Studies July 2018 1 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: FALLON First name: Garth Other name/s: Nil Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: MPhil School: Humanitiesand Social Sciences Faculty: UNSW Canberraat ADFA Title: Comprehensive encirclement: the Chinese Communist Party's strategy in Xinjiang Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASETYPE) This thesis argues that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has a strategy for securing Xinjiang - its far-flung predominantly Muslim most north-western province - through a planned program of Sinicisation. Securing Xinjiang would turna weakly defended 'back door' to China into a strategic strongpointfrom which Beijing canproject influence into Central Asia. The CCP's strategy is to comprehensively encircle Xinjiang with Han people and institutions, a Han dominated economy, and supporting infrastructure emanatingfrom inner China A successful program of Sinicisation would transform Xinjiang from a Turkic-language-speaking, largely Muslim, physically remote, economically under-developed region- one that is vulnerable to separation from the PRC - into one that will be substantially more culturally similar to, and physically connected with, the traditional Han-dominated heartland of inner China. Once achieved, complete Sinicisation would mean Xinjiang would be extremely difficult to separate from China. In Xinjiang, the CCP enacts policies in support of Sinication across all areas of statecraft. This thesis categorises these activities across three dimensions: the economic and demographic dimension, the political and cultural dimension, and the security and international cooperationdimension. -

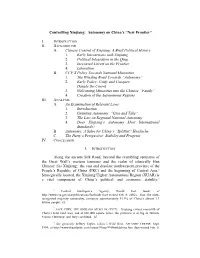

Controlling Xinjiang: Autonomy on China's “New Frontier”

Controlling Xinjiang: Autonomy on China’s “New Frontier” I. INTRODUCTION II. BACKGROUND A. Chinese Control of Xinjiang: A Brief Political History 1. Early Interactions with Xinjiang 2. Political Integration in the Qing 3. Increased Unrest on the Frontier 4. Liberation B. CCP’S Policy Towards National Minorities 1. The Winding Road Towards “Autonomy” 2. Early Policy: Unify and Conquer: Dangle the Carrot 3. Welcoming Minorities into the Chinese “Family” 4. Creation of the Autonomous Regions III. ANALYSIS A. An Examination of Relevant Laws 1. Introduction 2. Granting Autonomy: “Give and Take” 3. The Law on Regional National Autonomy 4. Does Xinjiang’s Autonomy Meet International Standards? B. Autonomy: A Salve for China’s “Splittist” Headache C. The Party’s Perspective: Stability and Progress IV. CONCLUSION I. INTRODUCTION Along the ancient Silk Road, beyond the crumbling remnants of the Great Wall’s western terminus and the realm of ethnically Han Chinese1 lies Xinjiang: the vast and desolate northwestern province of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the beginning of Central Asia.2 Strategically located, the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region (XUAR) is a vital component of China’s political and economic stability.3 1 Central Intelligence Agency, World Fact Book, at http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook (last visited Feb. 8, 2002). Han, the state- recognized majority nationality, comprise approximately 91.9% of China’s almost 1.3 billion people. Id. 2 JACK CHEN, THE SINKIANG STORY xx (1977). Xinjiang covers one-sixth of China’s total land area, and at 660,000 square miles, the province is as big as Britain, France, Germany, and Italy combined. -

Varieties of Patron-Client State Relationship

Varieties of Patron-Client State Relationship: The U.S. and Southeast Asia Hojung Do Ewha Womans University The United States (US) was one of the two superpowers during the Cold War and after the eventual demise of Soviet Union, consolidated its supremacy as sole hegemon of the world. US relations with many regions and many states have been extensively studied upon and in Asia, the relationship mostly dealt with China, Japan and South Korea. US patron relationship to Northeast Asia is relatively stable, durable, one consisting of visible and tangible security transactions such as military bases still stationed in South Korea and Japan. There is a wealth of literature to be found pertaining to Northeast Asia but US relationship with Southeast Asia is lacking compared to its neighbors. This paper starts with the following questions: Does a patron-client state relationship actually exist between the US Southeast Asia? Why is there a lack of patronage compared to one displayed in Northeast Asia? Is there room for maneuver for clients? How does US patronage change over time and in what way? The first part of this paper will briefly review previous literature on patron-client relationships. Second, key concepts of patron-client state relationships and the 6 types of relationships will be enumerated. Third, these relationships will be applied to three periods: 1965-67, 1975, 1985-87 in three countries: Indonesia, Philippines and Thailand to examine the trend of US patronage. Finally, implications and future modifications of this theory to Southeast Asia will be discussed. Patron-Client Relationship in Literature Patron-client relationship is not a fresh concept in the eyes of anthropology, sociology and even politics. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A study of the client kings in the early Roman period Everatt, J. D. How to cite: Everatt, J. D. (1972) A study of the client kings in the early Roman period, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10140/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk .UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM Department of Classics .A STUDY OF THE CLIENT KINSS IN THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE J_. D. EVERATT M.A. Thesis, 1972. M.A. Thesis Abstract. J. D. Everatt, B.A. Hatfield College. A Study of the Client Kings in the early Roman Empire When the city-state of Rome began to exert her influence throughout the Mediterranean, the ruling classes developed friendships and alliances with the rulers of the various kingdoms with whom contact was made. -

Killing Hope U.S

Killing Hope U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Part I William Blum Zed Books London Killing Hope was first published outside of North America by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London NI 9JF, UK in 2003. Second impression, 2004 Printed by Gopsons Papers Limited, Noida, India w w w.zedbooks .demon .co .uk Published in South Africa by Spearhead, a division of New Africa Books, PO Box 23408, Claremont 7735 This is a wholly revised, extended and updated edition of a book originally published under the title The CIA: A Forgotten History (Zed Books, 1986) Copyright © William Blum 2003 The right of William Blum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design by Andrew Corbett ISBN 1 84277 368 2 hb ISBN 1 84277 369 0 pb Spearhead ISBN 0 86486 560 0 pb 2 Contents PART I Introduction 6 1. China 1945 to 1960s: Was Mao Tse-tung just paranoid? 20 2. Italy 1947-1948: Free elections, Hollywood style 27 3. Greece 1947 to early 1950s: From cradle of democracy to client state 33 4. The Philippines 1940s and 1950s: America's oldest colony 38 5. Korea 1945-1953: Was it all that it appeared to be? 44 6. Albania 1949-1953: The proper English spy 54 7. Eastern Europe 1948-1956: Operation Splinter Factor 56 8. Germany 1950s: Everything from juvenile delinquency to terrorism 60 9. Iran 1953: Making it safe for the King of Kings 63 10. -

Citizens Without a State: Executive Summary

Citizens Without A State: Executive Summary By Howard Hills Foreword by former U.S. Attorney General Dick Thornburgh Dedication Jose Celso Barbosa was raised in poverty under Spanish colonial rule, and became the first black student at the Jesuit Seminary. He was Valedictorian at University of Michigan Medical School, and the first U.S. educated medical doctor in Puerto Rico. As a territorial Senator he advocated U.S. citizenship and statehood, was founder of island’s Republican Party. Renowned as a healer, humanitarian, and statesman, Barbosa smashed every barrier. To his courageous vision of a free and democratic Puerto Rico under the American flag this project is dedicated. Foreword: Dick Thornburgh President Reagan said it best in 1980: “As a ‘commonwealth’ Puerto Rico is now neither a state nor independent, and thereby has an historically unnatural status.” As a corollary, Howard Hills articulates the inescapable truism that “the primary democratic rights of national citizenship under the U.S. Constitution can exercised only through State citizenship.” For only citizens of a State admitted to the Union on equal footing with all other States are able to vote in federal elections, and thereby give consent to be governed by our nation’s leaders under the supreme law of the land. To Hills that means one thing: “Something called ‘U.S. citizenship’ without federal voting rights and equal representation in the federal political process is a cruel historical hoax.” *Howard Hills is the author of the book, Citizens Without A State. This is an Executive Summary of the book. *Dick Thornburgh, two-term Governor of Pennsylvania, Attorney General of the United States 1988- 1991, Undersecretary General of the United Nations, K & L Gates, LLP, Pittsburgh 1 Prologue For 119 years U.S. -

The Common Law Powers of the New York State Attorney General

THE COMMON LAW POWERS OF THE NEW YORK STATE ATTORNEY GENERAL Bennett Liebman* The role of the Attorney General in New York State has become increasingly active, shifting from mostly defensive representation of New York to also encompass affirmative litigation on behalf of the state and its citizens. As newly-active state Attorneys General across the country begin to play a larger role in national politics and policymaking, the scope of the powers of the Attorney General in New York State has never been more important. This Article traces the constitutional and historical development of the At- torney General in New York State, arguing that the office retains a signifi- cant body of common law powers, many of which are underutilized. The Article concludes with a discussion of how these powers might influence the actions of the Attorney General in New York State in the future. INTRODUCTION .............................................. 96 I. HISTORY OF THE OFFICE OF THE NEW YORK STATE ATTORNEY GENERAL ................................ 97 A. The Advent of Affirmative Lawsuits ............. 97 B. Constitutional History of the Office of Attorney General ......................................... 100 C. Statutory History of the Office of Attorney General ......................................... 106 II. COMMON LAW POWERS OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL . 117 A. Historic Common Law Powers of the Attorney General ......................................... 117 B. The Tweed Ring and the Attorney General ....... 122 C. Common Law Prosecutorial Powers of the Attorney General ................................ 126 D. Non-Criminal Common Law Powers ............. 136 * Bennett Liebman is a Government Lawyer in Residence at Albany Law School. At Albany Law School, he has served variously as the Executive Director, the Acting Director and the Interim Director of the Government Law Center. -

Community Matters in Xinjiang 1880–1949 China Studies

Community Matters in Xinjiang 1880–1949 China Studies Published for the Institute for Chinese Studies University of Oxford Editors Glen Dudbridge Frank Pieke VOLUME 17 Community Matters in Xinjiang 1880–1949 Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur By Ildikó Bellér-Hann LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 Cover illustration: Woman baking bread in the missionaries’ home (Box 145, sheet nr. 26. Hanna Anderssons samling). Courtesy of the National Archives of Sweden (Riksarkivet) and The Mission Covenant Church of Sweden (Svenska Missionskyrkan). This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bellér-Hann, Ildikó. Community matters in Xinjiang, 1880–1949 : towards a historical anthropology of the Uyghur / by Ildikó Bellér-Hann. p. cm — (China studies, ISSN 1570–1344 ; v. 17) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Uighur (Turkic people)—China— Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu—Social life and customs. 2. Uighur (Turkic people)—China— Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu—Religion. 3. Muslims—China—Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu. 4. Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu (China)—Social life and customs. 5. Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu (China)—Ethnic relations. 6. Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu (China)—History—19th century. I. Title. II. Series. DS731.U4B35 2008 951’.604—dc22 2008018717 ISSN 1570-1344 ISBN 978 90 04 16675 2 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Bee Round 3 Bee Round 3 Regulation Questions

NHBB Nationals Bee 2018-2019 Bee Round 3 Bee Round 3 Regulation Questions (1) This man's alleged last words were \The battle is at its height - wear my armor and beat my war drums. Do not announce my death." After his death, this man was given the title Chunmugong. A double agent plot led to the removal of this man in favor of a commander who was decisively defeated at the Battle of Chilchonryang. This man was killed during his final victory at the Battle of Noryang, after he defeated 330 Japanese ships with 13 at the Battle of Myeongnyang. For the point, name this \Nelson of the East", a Korean admiral who championed turtle ships. ANSWER: Yi Sun-Sin (2) A politician with this surname, the rival of Dave Pearce, had an affair with burlesque performer Blaze Starr. The Wall Street Journal, jokingly labeled a politician with this surname the \fourth branch of government" due to the immense power he wielded as chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. That man's father, another politician with this surname, was assassinated by Carl Weiss. The \Share Our Wealth Plan", which called for making \Every Man A King", was formulated by a member of, for the point, what Louisiana political dynasty whose members included Earl, Russell, and Huey? ANSWER: Long (accept Earl Long; accept Russell Long; accept Huey Long) (3) This region's inhabitants launched raids against its northern neighbors, called \harvesting the steppes," to fuel its slave trade, which was based out of Kefe. Haci Giray [ha-ji ge-rai] established this region's namesake khanate after breaking off from the Golden Horde. -

First Contact Between Ya'qūb Beg and the Qing

Journal of Asian and African Studies, No., Article First Contact between Ya‘qūb Beg and the Qing e Diplomatic Correspondence of * Shinmen, Yasushi Onuma, Takahiro e collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei includes a Turkic let- ter sent to the Qing Dynasty in early 1871 by Ya‘qūb Beg (1820?–77), who established a political regime over the oasis cities of Xinjiang in the late 19th century. Here we introduce this Turkic document and consider the activities and intentions of Ya‘qūb Beg at that time. e aim of this paper is to reveal new facts about contacts between Ya‘qūb Beg and the Qing Dynasty. In 1870, Ya‘qūb Beg went on an expedition to Turfan and Urumchi and extended his territory to the east. During this campaign, Ya‘qūb Beg released and returned the Qing officials captured in Turfan and Urumchi by the Tungans and sent this letter to the Qing. e letter carefully explains how his conquest and rule of Xinjiang were legitimate; his actions were rationalized as the will of God and thus beyond human intellect. From the letter, we appreciate Ya‘qūb Beg’s desire to have the Qing acknowledge that his rule was an accom- plished fact. The Qing authorities in Hami immediately replied with the “Letter of Admonition,” in which clearly states that Xinjiang was part of the Qing’s “dynastic territory.” At the same time, the authorities began to explore possi- bilities for cooperation not only with the local Chinese militias, but also with the Tungans for defense against Ya‘qūb Beg. -

These Sources Are Verifiable and Come From

0 General aim: To give institutions a report as unbiased, independent and reliable as possible, in order to raise the quality of the debate and thus the relative political decisions. Specific aims: To circulate this report to mass media and in public fora of various nature (i.e. human rights summits) as well as at the institutional level, with the purpose of enriching the reader’s knowledge and understanding of this region, given its huge implications in the world peace process. As is well known, for some years now highly politicised anti-Chinese propaganda campaigns have targeted the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, often spreading groundless, non-verifiable or outright false information, triggering on these bases a sanctions war and causing serious damage to international relations. There is a dramatic lack of unbiased and alternative documentation on the topic, especially by researchers who have lived and studied in China and Xinjiang. This report aims to fill this gap, by deepening and contextualising the region and its real political, economic and social dynamics, and offering an authoritative and documented point of view vis-à- vis the reports that Western politicians currently have at their disposal. The ultimate goal of this documentation is to promote an informed public debate on the topic and offer policymakers and civil society a different point of view from the biased and specious accusations coming from the Five Eyes countries, the EU and some NGOs and think-tanks. Recently some Swedish researchers have done a great job of deconstructing the main Western allegations about the situation in the autonomous region of Xinjiang.