Commencement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Growing Our Discipleship

Growing Our Discipleship ANNUAL REPORT FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016 JULY 1, 2015-JUNE 30, 2016 Overview Welcome from Archbishop Lori 1 Vision and Mission 2 Letter from Foundation President 3 Financials Year in Review 4 Investment Review 5 Performance Review 6 Selected Financial Information 7 Endowments Growing Our Discipleship 9 New Endowment Funds 12 Endowment Funds by Purpose 13 Donor Advised Funds 25 Legacy League 26 About the Foundation Foundation Leadership 29 Contact Us 31 Our Legacy 32 Dear Friends in Christ, In the summer of 2015, I issued my first pastoral letter as Archbishop of Baltimore, A Light Brightly Visible, Lighting the Path to Missionary Discipleship. In it, I asked the people of our Archdiocese to enter into a deeper relationship with Christ, to be not merely His disciples but His missionary disciples, extending the light of the Gospel to others among us so that they, too, could fully welcome His Word into their hearts. The Catholic Community Foundation is uniquely positioned to aid this evangelization effort for years to come. “Through their endowed giving, Foundation contributors are helping to foster a culture of Catholic growth and renewal.” Established in 1998 by my predecessor, Cardinal William H. Keeler, the Catholic Community Foundation has grown to over 470 separate funds, each with its own unique purpose and benefit. Not only are our parishes well-represented and supported by the Foundation, so too are our Catholic schools, clergy, religious and a host of ministries that are critically integral to carrying out the Church’s evangelizing work. Indeed, through their endowed giving, Foundation contributors are helping to foster a culture of Catholic growth and renewal. -

Commencement Prayer an Invocation By: Alexander Levering Kern, Executive Director of the Center for Spirituality, Dialogue, and Service

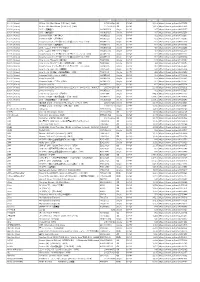

ommencement C 9 MAY 2021 CONTENTS This program is for ceremonial purposes only and is not to be considered an official confirmation of degree information. It contains only those details available at the publication deadline. History of Northeastern University 2 Program 5 Featured Speakers 10 Degrees in Course 13 Doctoral Degrees Professional Doctorate Degrees Bouvé College of Health Sciences Master's Degrees College of Arts, Media and Design Khoury College of Computer Sciences College of Engineering Bouvé College of Health Sciences College of Science College of Social Sciences and Humanities School of Law Presidential Cabinet 96 Members of the Board of Trustees, Trustees Emeriti, Honorary Trustees, and Corporators Emeriti 96 University Marshals 99 Faculty 99 Color Guard 100 Program Notes 101 Alma Mater 102 1 A UNIVERSITY ENGAGED WITH THE WORLD THE HISTORY OF NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY Northeastern University has used its leadership in experiential learning to create a vibrant new model of academic excellence. But like most great institutions of higher learning, Northeastern had modest origins. At the end of the nineteenth century, immigrants and first-generation Americans constituted more than half of Boston’s population. Chief among the city’s institutions committed to helping these people improve their lives was the Boston YMCA. The YMCA became a place where young men gathered to hear lectures on literature, history, music, and other subjects considered essential to intellectual growth. In response to the enthusiastic demand for these lectures, the directors of the YMCA organized the “Evening Institute for Young Men” in May 1896. Frank Palmer Speare, a well- known teacher and high-school principal with considerable experience in the public schools, was hired as the institute’s director. -

English-To-Korean Code Switching and Code Mixing in Korean Music Show After School Club Episode 191

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ENGLISH-TO-KOREAN CODE SWITCHING AND CODE MIXING IN KOREAN MUSIC SHOW AFTER SCHOOL CLUB EPISODE 191 AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By NATALIA PANTAS Student Number: 144214057 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2018 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ENGLISH-TO-KOREAN CODE SWITCHING AND CODE MIXING IN KOREAN MUSIC SHOW AFTER SCHOOL CLUB EPISODE 191 AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By NATALIA PANTAS Student Number: 144214057 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2018 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI GO FOR IT. NO MATTER HOW IT ENDS, IT WAS AN EXPERIENCE. -unknown- vii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI Dedicated to MY BELOVED PARENTS AND KPOP FANS ALL AROUND THE WORLD viii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I believe that in order to finish this thesis, we, as human beings definitely need others to support us. First of all, I would like to give thanks to Jesus Christ for His unconditional love and blessings so that I could finish this undergraduate thesis. Thank you Lord for everything You have done to me. I would like to give my deepest appreciation to my thesis advisor, Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M.Pd., M.A. for guiding me patiently in finishing my undergraduate thesis. -

43066321.Pdf

Expediente A Revista Brasileira de Física Médica (RBFM) é Corpo editoral uma publicação editada pela Associação Brasileira de Física Médica. Criada em 2005, tem como objetivo publicar trabalhos originais nas áreas de Radioterapia, Editor Científico Medicina Nuclear, Radiologia Diagnóstica, Proteção Marcelo Baptista de Freitas – Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP) Radiológica e Dosimetria das Radiações, incluindo Editores Associados modalidades correlatas de diagnóstico e terapia com Ana Maria Marques da Silva – Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS) radiações ionizantes e não-ionizantes, além de Ensino Denise Yanikian Nersissian – Instituto de Eletrotécnica e Energia da Universidade de São Paulo e Instrumentação em Física Médica. (IEE/USP) Lorena Pozzo – Instituto de Pesquisas Energéticas e Nucleares (IPEN-CNEN) Os conceitos e opiniões emitidos nos artigos são de Patrícia Nicolucci - Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade inteira responsabilidade de seus autores. É permitida de São Paulo (FFCLRP/USP) a reprodução total ou parcial dos artigos, desde que mencionada a fonte e mediante permissão expressa da RBFM. Conselho editorial Adilton de Oliveira Carneiro – Faculdade de José Willegaignon de Amorim de Carvalho – Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto Centro de Medicina Nuclear (HC-FMUSP) da Universidade de São Paulo (FFCLRP/USP) Kayo Okazaki – Instituto de Pesquisas Alberto Saburo Todo – Instituto de Pesquisas Energéticas e Nucleares, Comissão Nacional Energéticas -

Ficha Técnica Jogo a Jogo, 1992 - 2011

FICHA TÉCNICA JOGO A JOGO, 1992 - 2011 1992 Palmeiras: Velloso (Marcos), Gustavo, Cláudio, Cléber e Júnior; Galeano, Amaral (Ósio), Marquinhos (Flávio Conceição) e Elivélton; Rivaldo (Chris) e Reinaldo. Técnico: Vander- 16/Maio/1992 Palmeiras 4x0 Guaratinguetá-SP lei Luxemburgo. Amistoso Local: Dario Rodrigues Leite, Guaratinguetá-SP 11/Junho/1996 Palmeiras 1x1 Botafogo-RJ Árbitro: Osvaldo dos Santos Ramos Amistoso Gols: Toninho, Márcio, Edu Marangon, Biro Local: Maracanã, Rio de Janeiro-RJ Guaratinguetá-SP: Rubens (Maurílio), Mineiro, Veras, César e Ademir (Paulo Vargas); Árbitro: Cláudio Garcia Brás, Sérgio Moráles (Betinho) e Maizena; Marco Antônio (Tom), Carlos Alberto Gols: Mauricinho (BOT); Chris (PAL) (Américo) e Tiziu. Técnico: Benê Ramos. Botafogo: Carlão, Jefferson, Wilson Gottardo, Gonçalves e André Silva; Souza, Moisés Palmeiras: Marcos, Odair (Marques), Toninho, Tonhão (Alexandre Rosa) e Biro; César (Julinho), Dauri (Marcelo Alves) e Bentinho (Hugo); Mauricinho e Donizete. Técnico: Sampaio, Daniel (Galeano) e Edu Marangon; Betinho, Márcio e Paulo Sérgio (César Ricardo Barreto. Mendes). Técnico: Nelsinho Baptista Palmeiras: Velloso (Marcos), Gustavo (Chris), Roque Júnior, Cléber (Sandro) e Júnior (Djalminha); Galeano (Rodrigo Taddei), Amaral (Emanuel), Flávio Conceição e Elivél- 1996 ton; Rivaldo (Dênis) e Reinaldo (Marquinhos). Técnico: Vanderlei Luxemburgo. 30/Março/1996 Palmeiras 4x0 Xv de Jaú-SP 17/Agosto/1996 Palmeiras 5x0 Coritiba-PR Campeonato Paulista Campeonato Brasileiro Local: Palestra Itália Local: Palestra Itália Árbitro: Alfredo dos Santos Loebeling Árbitro: Carlos Eugênio Simon Gols: Alex Alves, Cláudio, Djalminha, Cris Gols: Luizão (3), Djalminha, Rincón Palmeiras: Velloso (Marcos), Gustavo (Ósio), Sandro, Cláudio e Júnior; Amaral, Flávio Palmeiras: Marcos, Cafu, Cláudio (Sandro), Cléber e Júnior (Fernando Diniz); Galeano, Conceição, Rivaldo (Paulo Isidoro) e Djalminha; Müller (Chris) e Alex Alves. -

Fenomén K-Pop a Jeho Sociokulturní Kontexty Phenomenon K-Pop and Its

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra hudební výchovy Fenomén k-pop a jeho sociokulturní kontexty Phenomenon k-pop and its socio-cultural contexts Diplomová práce Autorka práce: Bc. Eliška Hlubinková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Filip Krejčí, Ph.D. Olomouc 2020 Poděkování Upřímně děkuji vedoucímu práce Mgr. Filipu Krejčímu, Ph.D., za jeho odborné vedení při vypracovávání této diplomové práce. Dále si cením pomoci studentů Katedry asijských studií univerzity Palackého a členů české k-pop komunity, kteří mi pomohli se zpracováním tohoto tématu. Děkuji jim za jejich profesionální přístup, rady a celkovou pomoc s tímto tématem. Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a dalších informačních zdrojů. V Olomouci dne Podpis Anotace Práce se zabývá hudebním žánrem k-pop, historií jeho vzniku, umělci, jejich rozvojem, a celkovým vlivem žánru na společnost. Snaží se přiblížit tento styl, který obsahuje řadu hudebních, tanečních a kulturních směrů, široké veřejnosti. Mimo samotnou podobu a historii k-popu se práce věnuje i temným stránkám tohoto fenoménu. V závislosti na dostupnosti literárních a internetových zdrojů zpracovává historii žánru od jeho vzniku až do roku 2020, spolu s tvorbou a úspěchy jihokorejských umělců. Součástí práce je i zpracování dvou dotazníků. Jeden zpracovává názor české veřejnosti na k-pop, druhý byl mířený na českou k-pop komunitu a její myšlenky ohledně tohoto žánru. Abstract This master´s thesis is describing music genre k-pop, its history, artists and their own evolution, and impact of the genre on society. It is also trying to introduce this genre, full of diverse music, dance and culture movements, to the public. -

Massachusetts Licensed Motor Vehicle Damage Appraisers - Individuals September 05, 2021

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS DIVISION OF INSURANCE PRODUCER LICENSING 1000 Washington Street, Suite 810 Boston, MA 02118-6200 FAX (617) 753-6883 http://www.mass.gov/doi Massachusetts Licensed Motor Vehicle Damage Appraisers - Individuals September 05, 2021 License # Licensure Individual Address City State Zip Phone # 1 007408 01/01/1977 Abate, Andrew Suffolk AutoBody, Inc., 25 Merchants Dr #3 Walpole MA 02081 0-- 0 2 014260 11/24/2003 Abdelaziz, Ilaj 20 Vine Street Lexington MA 02420 0-- 0 3 013836 10/31/2001 Abkarian, Khatchik H. Accurate Collision, 36 Mystic Street Everett MA 02149 0-- 0 4 016443 04/11/2017 Abouelfadl, Mohamed N Progressive Insurance, 2200 Hartford Ave Johnston RI 02919 0-- 0 5 016337 08/17/2016 Accolla, Kevin 109 Sagamore Ave Chelsea MA 02150 0-- 0 6 010790 10/06/1987 Acloque, Evans P Liberty Mutual Ins Co, 50 Derby St Hingham MA 02018 0-- 0 7 017053 06/01/2021 Acres, Jessica A 0-- 0 8 009557 03/01/1982 Adam, Robert W 0-- 0 West 9 005074 03/01/1973 Adamczyk, Stanley J Western Mass Collision, 62 Baldwin Street Box 401 MA 01089 0-- 0 Springfield 10 013824 07/31/2001 Adams, Arleen 0-- 0 11 014080 11/26/2002 Adams, Derek R Junior's Auto Body, 11 Goodhue Street Salem MA 01970 0-- 0 12 016992 12/28/2020 Adams, Evan C Esurance, 31 Peach Farm Road East Hampton CT 06424 0-- 0 13 006575 03/01/1975 Adams, Gary P c/o Adams Auto, 516 Boston Turnpike Shrewsbury MA 01545 0-- 0 14 013105 05/27/1997 Adams, Jeffrey R Rodman Ford Coll Ctr, Route 1 Foxboro MA 00000 0-- 0 15 016531 11/21/2017 Adams, Philip Plymouth Rock Assurance, 901 Franklin Ave Garden City NY 11530 0-- 0 16 015746 04/25/2013 Adams, Robert Andrew Country Collision, 20 Myricks St Berkley MA 02779 0-- 0 17 013823 07/31/2001 Adams, Rymer E 0-- 0 18 013999 07/30/2002 Addesa, Carmen E Arbella Insurance, 1100 Crown Colony Drive Quincy MA 02169 0-- 0 19 014971 03/04/2008 Addis, Andrew R Progressive Insurance, 300 Unicorn Park Drive 4th Flr Woburn MA 01801 0-- 0 20 013761 05/10/2001 Adie, Scott L. -

Jamaica Plain Gazette

MAXFIELD & COMPANY (617) 293-8003 REALEXPERIENCE ESTATE • EXCELLENCE FAULKNER HOSPITAL EXPANSIONMAKE EVERY PLANS, DAY PAGE, EARTH 10 DAY Vol. 30 No. 8 28 Pages • Free Delivery 25 Cents at Stores BOOK YOUR Jamaica Plain POST IT Call Your Advertising Rep Printed on (617)524-7662 Recycled Paper AZETTE 617-524-2626 G MAY 14, 2021 WWW.JAMAICAPLAINGAZETTE.COM Barros, Santiago help stuff gift MOTHER’S DAY LILAC WALK AT ARBORETUM bags for senior mothers as part of ‘I Remember Mama’ event BY LAUREN BENNETT VOAMASS’s Shiloh House on Parley Vale, a place for women JP-based nonprofit Volun- recovering from substance abuse teers of America of Massachu- disorder and behavioral health setts (VOAMASS) held its 26th conditions. annual ‘I Remember Mama’ VOAMASS offers programs event on May 8, but this year, and services for behavioral the event looked a little different. health, veterans, seniors, and The program is typically a re-entry services for formerly brunch held at a hotel for around incarcerated individuals. 200 senior mothers who live in “As a candidate for mayor public housing in Boston, but of Boston, it’s really important this year, because of the pan- that we learn what’s happening demic, volunteers and mayoral in the community, and more im- candidates John Barros and Jon portantly,” what else can be done Shown above, several friends in the Arnold Arboretum joined Santiago created 200 gift bags to support residents, John Barros Acting Mayor Kim Janey, and her mother Phyllis, for a Lilac that were delivered to the women said at the event. -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

NGA | 2017 Annual Report

N A TIO NAL G ALL E R Y O F A R T 2017 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Board of Trustees COMMITTEE Buffy Cafritz (as of September 30, 2017) Frederick W. Beinecke Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Louisa Duemling Mitchell P. Rales Aaron Fleischman Sharon P. Rockefeller Juliet C. Folger David M. Rubenstein Marina Kellen French Andrew M. Saul Whitney Ganz Sarah M. Gewirz FINANCE COMMITTEE Lenore Greenberg Mitchell P. Rales Rose Ellen Greene Chairman Andrew S. Gundlach Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary of the Treasury Jane M. Hamilton Richard C. Hedreen Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Helen Lee Henderson Chairman President David M. Rubenstein Kasper Andrew M. Saul Mark J. Kington Kyle J. Krause David W. Laughlin AUDIT COMMITTEE Reid V. MacDonald Andrew M. Saul Chairman Jacqueline B. Mars Frederick W. Beinecke Robert B. Menschel Mitchell P. Rales Constance J. Milstein Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Pappajohn Sally Engelhard Pingree David M. Rubenstein Mitchell P. Rales David M. Rubenstein Tony Podesta William A. Prezant TRUSTEES EMERITI Diana C. Prince Julian Ganz, Jr. Robert M. Rosenthal Alexander M. Laughlin Hilary Geary Ross David O. Maxwell Roger W. Sant Victoria P. Sant B. Francis Saul II John Wilmerding Thomas A. Saunders III Fern M. Schad EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Leonard L. Silverstein Frederick W. Beinecke Albert H. Small President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Michelle Smith Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III United States Director Benjamin F. Stapleton III Franklin Kelly Luther M. -

In Memoriam: Pray for the Deceased Clergy of the Archdiocese of Baltimore

In Memoriam: Pray for the deceased clergy of the Archdiocese of Baltimore Please pray for these members of the clergy who served in the Archdiocese of Baltimore and died in the months of May through December. MAY May 2 Father Felix Barrotti, 1881+ Monsignor Eugene J. Connelly, 1942+ Monsignor William F. Doyle, 1976+ Father Pompeo Vadacca, C.M., 1982+ May 3 Father Mark Rawinisz, O.F.M. Conv., 1956+ Deacon Harry Carpenter, 2005+ May 4 Monsignor Clare J. O’Dwyer, 1982+ Monsignor Edward R. Braham, 1984+ Father Jeffrey W. Carlsen, 2005+ May 5 Father William A. Richardson, S.S.J., 2005+ May 6 Monsignor Edward L. Buckey, 1948+ Monsignor Francis J. Childress, 1991+ Monsignor William T. McCrory, 1993+ Father John A. Delclos, 2007+ May 7 Father Joseph P. Josaitis, 1980+ Deacon William H. Kohlmann, 1986+ May 9 Father Joseph J. Dulski, 1906+ Monsignor W. Paul Smith, 1946+ Father Joseph D. Fuller, 1969+ Father Robert E. Lee Aycock, S.S., 1977+ Father Thomas Simmons, 1987+ Father John F. Kresslein, C.Ss.R., 1992+ May 10 Father John J. Bowens, 1925+ Father John J. Reilly, 1949+ Father Joseph A. Stepanek, C.Ss.R., 1955+ Father Joseph A. Graziani, 1966+ Monsignor Edwin A. DeLawder, 1980+ Monsignor John C. Collopy, 2015+ May 11 Father Paul John Sandalgi, 1960+ Deacon John J. Boscoe Jr., 2014+ May 12 Father Patrick J. O’Connell, 1924+ Monsignor William J. Sweeney, 1967+ Father Claude M. Kinlein, 1976+ Monsignor Joseph M. Nelligan, 1978+ Monsignor Edward F. Staub, 2000+ May 13 Father James Sterling, 1905+ Father Theodore S. Rowan, 1989+ May 14 Father Edward L. -

Mã Số Tên Bài Hát Ca Sĩ

MÃ SỐ TÊN BÀI HÁT CA SĨ 607369 0932 陈小春 605670 1 Thing Amerie 604498 1.2.3.4 Plain White T S 601035 1+1 邓颖芝 602573 100个太阳月亮(HD) 棉花糖 606378 102% Love Akon 601398 10年后の君へ(HD) 板野友美 602810 1234(HD) 韩智恩 604458 143 Bobby Brackins&Ray J 603991 16@war Karina 601320 1874(hd) 陈奕迅 604743 1901 Phoenix 604872 1973 James Blunt 605446 1985 Bowling For Soup 604538 2 In The Morning New Kids On The Block 606203 2 Out Of Three Ain't Bad Meatloaf 603742 2002年的第一场雪 刀郎 601796 2010等你来(HD) 群星 601674 2012(hd) 五月天 602527 2020爱你爱你(HD) BY2 604016 21st Century Life Sam Sparro 607004 21个人 游鸿明 606119 24楼 刘若英&杨坤 605128 25 Minutes Michael Learns To Rock 607063 281公里 谢霆锋 605430 281公里 谢霆锋 603515 4 55 Uk 602431 4 In Love(HD) 陈豪 604846 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 605333 4:55 Unknown 604954 500 Miles Unknown 601149 5151 任贤齐 601133 7 Days Energy 604481 7 Things Miley Cyrus 604687 7 Years And 50 Days Groove Coverage 605889 808 郑秀文 602467 9:55pm(HD) 薛凯琪 602962 920(HD) A-Lin&小宇 601804 955pm(hd) 薛凯琪 601084 99姑娘酒窝 罗百吉 606646 A B C Unknown 605298 A Better Day 刘德华 605416 A Better Life Jade Giải Pháp Karaoke hàng đầu Việt Nam: www.vietktv.vn Trang 1 MÃ SỐ TÊN BÀI HÁT CA SĨ 604921 A Little Bit Unknown 604525 A Little Gasoline Terri Clark 605604 A Little Love 冯曦妤 604228 A Love Theme Olivia 605122 A Man Without Love Unknown 604881 A Moment Like This Leona Lewis 604853 A New Day Has Come Celinedion 605407 A Reason To Believe Tim Hardin 603648 A Summer Place Unknown 604933 A Thousand Dreams Of You 张国荣 601472 A Thousand Years(hd) Christina Perri 603242 A Whiter Shade Of Pale Procol Harum