Draft Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement for Revision of the Coronado National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Molecular Phylogenetic Study of Graptopetalum (Crassulaceae) Based on Ets, Its, Rpl16, and Trnl-F Nucleotide Sequences1

American Journal of Botany 91(7): 1099±1104. 2004. A MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC STUDY OF GRAPTOPETALUM (CRASSULACEAE) BASED ON ETS, ITS, RPL16, AND TRNL-F NUCLEOTIDE SEQUENCES1 RAUÂ L ACEVEDO-ROSAS,2,3 KENNETH CAMERON,4 VICTORIA SOSA,2,5 AND SUSAN PELL4 2Instituto de EcologõÂa, A.C. Apartado Postal 63, 91000 Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico; 3Departamento de GeografõÂa, CUCSH, Universidad de Guadalajara, Av. de los Maestros y M. BaÂrcena, 44120 Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico; 4The Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Program for Molecular Systematics Studies, The New York Botanical Garden, 200th St. and Southern Blvd., Bronx, New York 10458-5126 USA Nuclear ETS and ITS, as well as plastid rpl16 and trnL-F DNA sequences were used to determine relationships among species of Graptopetalum (Crassulaceae) and closely related genera. Graptopetalum is member of a group of taxa restricted to North America, one of the centers of diversity of Crassulaceae; however, their phylogenetic relationships are not yet understood. Nineteen species of Graptopetalum and 24 species from nine other genera of Crassulaceae were sampled for use in three separate parsimony analyses: ITS alone, ETS alone, and a combined nuclear 1 plastid DNA analysis using all four gene regions. The ETS data set had the highest number of parsimony-informative sites, about 30% more than in ITS, but the most fully resolved tree resulted when the four DNA regions were combined. Only four subclades of the tree received moderate to strong bootstrap support, one of which includes all species of Graptopetalum having a single whorl of stamens. However, Graptopetalum is not monophyletic. Instead, Tacitus bellus and select species of Cremnophila, Sedum, and Echeveria are interspersed among species of Graptopetalum and show evidence of grouping according to geographical range of distribution more so than habit or ¯oral morphology. -

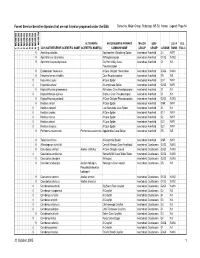

Sensitive Species That Are Not Listed Or Proposed Under the ESA Sorted By: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci

Forest Service Sensitive Species that are not listed or proposed under the ESA Sorted by: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci. Name; Legend: Page 94 REGION 10 REGION 1 REGION 2 REGION 3 REGION 4 REGION 5 REGION 6 REGION 8 REGION 9 ALTERNATE NATURESERVE PRIMARY MAJOR SUB- U.S. N U.S. 2005 NATURESERVE SCIENTIFIC NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME(S) COMMON NAME GROUP GROUP G RANK RANK ESA C 9 Anahita punctulata Southeastern Wandering Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G4 NNR 9 Apochthonius indianensis A Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1G2 N1N2 9 Apochthonius paucispinosus Dry Fork Valley Cave Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 Pseudoscorpion 9 Erebomaster flavescens A Cave Obligate Harvestman Invertebrate Arachnid G3G4 N3N4 9 Hesperochernes mirabilis Cave Psuedoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G5 N5 8 Hypochilus coylei A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G3? NNR 8 Hypochilus sheari A Lampshade Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 NNR 9 Kleptochthonius griseomanus An Indiana Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Kleptochthonius orpheus Orpheus Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 9 Kleptochthonius packardi A Cave Obligate Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 N2N3 9 Nesticus carteri A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid GNR NNR 8 Nesticus cooperi Lost Nantahala Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Nesticus crosbyi A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1? NNR 8 Nesticus mimus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2 NNR 8 Nesticus sheari A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR 8 Nesticus silvanus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR -

Crassulaceae

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227205999 Crassulaceae Chapter · April 2007 DOI: 10.1007/978-3-540-32219-1_12 CITATIONS READS 31 417 2 authors: Joachim Thiede Urs Eggli 88 PUBLICATIONS 183 CITATIONS 65 PUBLICATIONS 584 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Ecology and ecophysiology of desert plants in the Succulent Karoo, Namib, Negev, Sahara and other drylands View project Contributions to the succulent flora of Malawi View project All content following this page was uploaded by Joachim Thiede on 19 May 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Crassulaceae 93 r- subfa- clade taxon distribution ::"spp.tribe mily family 5 Slnocrassu/a l EI t- to I Kungia l, , .r Meterostachys ä f f f;mnerate lsl to I F Orostachys Append. subs. I Hytotetephium ) t!_il'l Umbilicus Rhodiola I Pseudosedum I temoerate t Rhodiota atiu 1e Medit') i F] f ) l"l Phedimus I E_l Sempervivum Europe/N.East rytvum S. assyrlacum Near East [G] N S. mooneyifG] NE Africa l=l ; EItEI lo I Petrosedum Eurooe/Medit. I,l lll - l"l n- Aeonium S. ser. Pubescens [G] I t--l S. ser. Caerulea lGl INorthAfrica tl rl, ) S. ser. Monanthoidea [G] -{ ES Aichryson tsl .))t\ Monanthes Macaronesia l'l r- Aeonium ] E] 1e S. magel/ense[G] ! rP S. dasyphyllum [G] S. tydium l-t ic lGl l.l ae Rosularia Europe/ Mediterranean/ l'l S. sedoides l'l [G] 'Leuco- Near EasV tl S. -

Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 90-Day Finding on a Petition To

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 08/08/2012 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2012-19334, and on FDsys.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 [Docket No. FWS-R2-ES-2012-0047] [4500030113] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 90-Day Finding on a Petition to List Graptopetalum bartramii (Bartram Stonecrop) and Pectis imberbis (Beardless Chinch Weed) as Endangered or Threatened and Designate Critical Habitat AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Notice of petition finding and initiation of status review. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), announce a 90-day finding on a petition to list Graptopetalum bartramii (Bartram stonecrop) and Pectis imberbis (beardless chinch weed) as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act), and to designate critical habitat. Based on our review, we find that the petition presents substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that listing Bartram stonecrop and beardless chinch weed may be warranted. Therefore, with the publication of this notice, we will initiate a review of the status of these species to determine if listing Bartram stonecrop or beardless chinch weed, or both, is warranted. To ensure that our status review is comprehensive, we request scientific and commercial data and other information regarding these species. Based on the status review, we will issue a 12-month finding on the petition, which will address whether the petitioned action is warranted, as provided in section 4(b)(3)(B) of the Act. -

Phylogenetic Relationships and Evolution in Dudleya (Crassulaceae) Author(S): Jenn M

Phylogenetic Relationships and Evolution in Dudleya (Crassulaceae) Author(s): Jenn M. Yost , Megan Bontrager , Stephen Ward McCabe , Darren Burton , Michael G. Simpson , Kathleen M. Kay , and Matt Ritter Source: Systematic Botany, 38(4):1096-1104. 2013. Published By: The American Society of Plant Taxonomists URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1600/036364413X674760 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Systematic Botany (2013), 38(4): pp. 1096–1104 © Copyright 2013 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists DOI 10.1600/036364413X674760 Phylogenetic Relationships and Evolution in Dudleya (Crassulaceae) Jenn M. Yost,1,4,6 Megan Bontrager,1,5 Stephen Ward McCabe,2 Darren Burton,3 Michael G. Simpson,3 Kathleen M. Kay,1 and Matt Ritter4 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Santa Cruz, 1156 High Street, California 95064, U. -

An Annotated List of VASCULAR PLANTS of CHIRICAHUA MOUNTAINS

An Annotated List of VASCULAR PLANTS of CHIRICAHUA MOUNTAINS Including Pedregosa Mountains, Swisshelm Mountains Chiricahua National Monument, and Fort Bowie National Historic Site Peter S. Bennett R. Roy Johnson Michael R. Kunzmann Special Report No. 12 October 1996 United States Geological Survey Biological Resources Division Cooperative Park Studies Unit School of Renewable Natural Resources 125 Biological Sciences East University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 Authors Peter S. Bennett Michael R. Kunzmann USGS Biological Resources Division USGS Biological Resources Division Cooperative Park Studies Unit Cooperative Park Studies Unit The University of Arizona The University of Arizona 125 Biological Sciences East 125 Biological Sciences East Tucson, Arizona 85721 Tucson, Arizona 85721 R. Roy Johnson 3755 Hunters Run Tucson, Arizona 85730 Unit Personnell William L. Halvorson, Unit Leader Joan Ford, Research Unit Assistant Peter S. Bennett, Research Ecologist Gloria J. Maender, Editorial Assistant Cecil R. Schwalbe, Research Ecologist Mary N. Greene, Secredary Michael R. Kunsmann, Ecologist Tod A. Gregoire, Word Processing Specialist Katherine L. Hiett, Biological Technician 520/670-6885 520/621-1174 FTS 520/670-6885 Reports in this series are produced in limited quantities. As long as the supply lasts, copies may be obtained from BRD-CPSU/UA, 125 Biological Sciences East, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721. This report was printed on recycled paper. CONTENTS List of Figures .............................................................................................................................. -

Petition to List Two Arizona Plants from the Sky Islands As Threatened Or Endangered Under the Endangered Species Act

PETITION TO LIST TWO ARIZONA PLANTS FROM THE SKY ISLANDS AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT Graptopetalum bartramii © Alan Cressler CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY July 7, 2010 July 7, 2010 TO: Mr. Ken Salazar CC: Dr. Benjamin Tuggle Secretary of the Interior Southwest Regional Director 18th and "C" Street, N.W. P.O. Box 1306 Washington, D.C. 20240 Albuquerque, NM 87103-1306 [email protected] Dear Secretary Salazar: Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. §1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. §424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity, Tierra Curry, and Noah Greenwald hereby formally petition the Secretary of Interior to list Bartram stonecrop (Graptopetalum bartramii), and beardless chinch weed (Pectis imberbis), two rare Arizona plants from the Madrean Sky Islands, as Threatened or Endangered species and to designate critical habitat concurrent with listing. Petitioners file this petition under the Endangered Species Act, 16 U.S.C. sections 1531-1543 (1982). This petition is filed under 5 U.S.C. section 553(e), and 50 C.F.R. part 424.14 (1990), which grants interested parties the right to petition for issuance of a rule from the Assistant Secretary of the Interior. The petitioners request that Critical Habitat be designated as required by 16 U.S.C. 1533(b)(6)(C) and 50 CFR 424.12, and pursuant to the Administrative Procedures Act (5 U.S.C. 553). Petitioners realize this petition sets in motion a specific process placing definite response requirements on the FWS and very specific time constraints upon those responses. -

Chapter 4: Ecological & Biological Diversity of the Coronado National Forest

4. Chapter 4: Ecological & Biological Diversity of the Coronado National Forest In Ecological and Biological Diversity of National Forests in Region 3 Bruce Vander Lee, Ruth Smith, and Joanna Bate The Nature Conservancy Table of Contents Table of Contents ...........................................................................................................4-1 List of Tables ..................................................................................................................4-2 List of Figures.................................................................................................................4-4 Introduction....................................................................................................................4-6 Results .............................................................................................................................4-7 I. Potential Natural Vegetation Types within the Coronado National Forest.............4-7 III. Riparian and Freshwater Systems and Species..................................................4-13 IV. Plant and Animal Species Richness ...................................................................4-18 Discussion......................................................................................................................4-33 4-1 List of Tables Table 4-1. Approximate area (acres) and percent of total area of potential natural vegetation types on the Coronado National Forest. Areas were calculated using data from The Southwest Regional Gap Analysis -

Species Status Assessment for Graptopetalum Bartramii

Species Status Assessment Report for Graptopetalum bartramii Bartram’s stonecrop April 2018 Southwest Region United States Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Office Tucson, Arizona i This document was prepared by Julie Crawford, Arizona Ecological Services Office and Hayley Dikeman, Southwest Regional Office. We thank Angela Anders, Southwest Regional Office, for reviews of drafts. Valuable input was provided by George Ferguson, University of Arizona; Steve Buckley, National Park Service; George Montgomery, formerly of the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum; Jessica Simms, National Park Service; Angela Barclay, National Forest Service, and Kathryn Kennedy, National Forest Service. ii Suggested reference: United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Species status assessment report for Graptopetalum bartramii (Bartram’s stonecrop). United States Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Office, Tucson, Arizona. 117 pp. + 2 appendices. iii Species Status Assessment Report for Graptopetalum bartramii Bartram’s stonecrop Prepared by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This species status assessment reports the results of the comprehensive status review for Graptopetalum bartramii (Bartram’s stonecrop) through an analytical approach assessing the species needs, current status, and future status of a species using the best available information, and provides a thorough account of the species’ overall viability. For the purpose of this assessment, we generally define viability as the ability of G. bartramii to sustain populations in natural systems over time. The SSA Framework uses the conservation biology principles of resiliency, redundancy, and representation (collectively known as the “3Rs”) as a lens to evaluate the current and future condition of the species. Graptopetalum bartramii is a succulent of the Crassulaceae or stonecrop family. -

Addisoniacolored11newy.Pdf

ADDISONIA COLORED ILLUSTRATIONS AND POPULAR DESCRIPTION OF PLANTS Volume 11 1926 LIBKARY New YORK ttO!ANiCAL PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK BOTANICAL GARDEN (ADDISON BROWN FUND) THB SCIENCE PEES3 PEINTINQ COMPANY LANCASTER, PA. CONTENTS Part 1 JUNB 30, 1926 PLATE PAG:B 353 Graptopetalum Bartramii 1 354 Thunbergia Gibsoni 3 355 Chelone glabra 5 356 Tecomaria capensis 7 357 Osmia borinquensis 9 358 I^apeyrousia cruenta 11 359 Allophyton mexicanum 13 360 Lycoris squamigera 15 Part 2 October 13, 1926 361 Erythronium americanum 17 362 Ginkgo biloba 19 /^ 363 L,espedeza Sieboldii 21 364 Cercidiphyllum japonicum ... 23 365 Nymphoides Humboldtianum 25 366 Catharanthus roseus 27 367 Primula kewensis 29 368 Gaillardia Amblyodon 31 Part 3 December 9, 1926 369 Deeringothamnus pulchellus 33 370 Azalea viscosa glauca 35 371 Teedia lucida 37 372 Turraea floribunda 39 373 Corylus pontica 41 374 Eryngium aquaticum 43 375 Pinus peuce 45 376 Ilex decidua 47 iii iv Addisonia Part 4 January 5. 1927 377 Torenia Fournieri 49 378 Desmothamnus lucidus 51 379 Tricyrtis hirta 53 380 Adenoropium Berlandieri 55 381 Helianthus tuberosus 57 382 Aubrietia deltoidea 59 383 Triphora trianthopliora 61 384 Ipomoea quinquefolia 63 Index 65 i.^:-^^-''^^:;''^-^m-l.;:s:t;^ ADDISONIA COLORED ILLUSTRATIONS AND POPULAR DESCRIPTIONS OF PLANTS Volume 11 Number 1 MARCH, 1926 PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK BOTANICAL GARDEN (ADDISON BROWN FUND) JUNE 30, 1926 ANNOUNCEMENT A bequest made to the New York Botanical Garden by its late President, Judpe Addison Brown, established the ADDISON BROWN FUND -

Graptopetalum (Crassu- Laceae) in Arizona 13 Hybridization of a Rare San Francisco Peaks Endemic, Echinocactus Horizonthalonius Flower

The Plant Press THE ARIZONA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY Volume 36, Number 2 Fall 2013 In this Issue: Habitat and Rare Plant Conservation 1 In Search of Amoreuxia and Echinocactus in Sonora 4 Ethnobotany of Amoreuxia 7 Prolonged Vegetative Dor- mancy in Rare Plant Species 9 Graptopetalum (Crassu- laceae) in Arizona 13 Hybridization of a Rare San Francisco Peaks Endemic, Echinocactus horizonthalonius flower. Packera franciscana 16 New Ideas about Rarity of Carex Species In Search of Amoreuxia and 13 Applied Conservation Botany: Examples from Echinocactus in Sonora Wyoming and the Colorado by Thomas R. Van Devender1 and Ana L. Reina-Guerrero Plateau Photos courtesy the authors Plus One of the tools that helps States and landowners plan and implement projects to 6 Honoring Julia Fonseca conserve species is the Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund (section 6 of the U.S. Endangered Species Act), which provides grants to States and Territories 19 Remembering Doug Green to participate in a wide array of voluntary conservation projects for candidate, & Our Regular Features proposed, and listed species on non-Federal lands. Section 6 surveys in Arizona and Sonora are very important in understanding the current statuses of Threatened and 2 President’s Note Endangered plants, and opportunities for general floristic inventories in the habitats 8 Who’s Who at AZNPS where they occur. 11, 12 & 15 Books! We surveyed populations of Santa Rita mountain yellowshow (Amoreuxia gonzalezii) 15 Spotlight on a Native Plant and Turk’s head cactus (Echinocactus horizonthalonius) in Sonora, Mexico, under Section 6 funding. continued page 3 ©2013 Arizona Native Plant Society. -

Sonoran Desert Research Center

Powell, Halvorson, Schmidt In Cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Saguaro National Park, Rincon Mountain District Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Saguaro National Park, Rincon Mountain District Plant and Vertebrate Vascular U.S. Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center 2255 N. Gemini Drive Flagstaff, AZ 86001 Open-File Report 2006-1075 Southwest Biological Science Center Open-File Report 2006-1075 November 2006 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey National Park Service In cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Saguaro National Park, Rincon Mountain District Edited by Brian F. Powell, William L. Halvorson, and Cecilia A. Schmidt Open-File Report 2006-1075 November 2006 USGS Southwest Biological Science Center Sonoran Desert Research Station U.S. Department of the Interior University of Arizona U.S. Geological Survey School of Natural Resources 125 Biological Sciences East National Park Service Tucson, Arizona 85721 U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS-the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web:http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested Citation Powell, B. F, W. L. Halvorson, and C. A. Schmidt. Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Saguaro National Park, Rincon Mountain District.