Building a Network of Safety in Nepal's Mountain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feasibility Study of Kailash Sacred Landscape

Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation Initiative Feasability Assessment Report - Nepal Central Department of Botany Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Nepal June 2010 Contributors, Advisors, Consultants Core group contributors • Chaudhary, Ram P., Professor, Central Department of Botany, Tribhuvan University; National Coordinator, KSLCI-Nepal • Shrestha, Krishna K., Head, Central Department of Botany • Jha, Pramod K., Professor, Central Department of Botany • Bhatta, Kuber P., Consultant, Kailash Sacred Landscape Project, Nepal Contributors • Acharya, M., Department of Forest, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation (MFSC) • Bajracharya, B., International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) • Basnet, G., Independent Consultant, Environmental Anthropologist • Basnet, T., Tribhuvan University • Belbase, N., Legal expert • Bhatta, S., Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation • Bhusal, Y. R. Secretary, Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Das, A. N., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Ghimire, S. K., Tribhuvan University • Joshi, S. P., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Khanal, S., Independent Contributor • Maharjan, R., Department of Forest • Paudel, K. C., Department of Plant Resources • Rajbhandari, K.R., Expert, Plant Biodiversity • Rimal, S., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Sah, R.N., Department of Forest • Sharma, K., Department of Hydrology • Shrestha, S. M., Department of Forest • Siwakoti, M., Tribhuvan University • Upadhyaya, M.P., National Agricultural Research Council -

Studies on the Most Traded Medicinal Plants from the Dolpa District of Nepal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Toyama Repository STUDIES ON THE MOST TRADED MEDICINAL PLANTS FROM THE DOLPA DISTRICT OF NEPAL Mohan B. Gewali Division of Visiting Professors Institute of Natural Medicine University of Toyama Abstract The traditional uses, major chemical constituents and prominent biological activities of the most traded medicinal plants from Dolpa district of Nepal are described in this article. Cradled on the laps of the central Himalayan range, Nepal (147,181 Km2) is sandwiched between two Asian giants, India on the South and China on the North. Nepal is divided into 14 zones and 75 districts. The Karnali zone, which has a border with Tibet region of China, is made up of five districts. Dolpa district (7,889 km²) is one of them. Dolpa district’s topography starts from the subtropical region (1575 meter) and ends in the nival region (6883 meter) in the trans-Himalayan region. The district has a population of about 29545 with Hindu 60%, Buddhist 40% including 5.5% ancient Bonpo Religion. Major ethnic groups/castes belonging to both Hindu and Buddhist religions include Kshetri, Dangi, Rokaya, Shahi, Buda, Thakuri, Thakulla, Brahmins, Karki, Shrestha, Sherpa and other people of Tibetan origin. The languages spoken are Nepali, Dolpo and Kaike. Dolpo is a variant of the Tibetan language. Kaike is considered indigenous language of Tichurong valley. In the Dolpa district, the traditional Tibetan medical practices are common. The traditional Tibetan practitioners called the Amchis provide the health care service. The Amchis have profound knowledge about the medicinal herbs and the associated healing properties of the medicinal plants found in the Dolpa district. -

Upper Dolpo Trek - 26 Days

Upper Dolpo Trek - 26 days Go on 26 days trip for $ per person Trekking in the Dolpo region has only been permitted since mid-1989. The region lies to the west of the Kali Gandaki Valley, Dolpo is located inside the Shey-Phoksundo National Park in mid-western Nepal, behind the Dhaulagiri massif, towards the Tibetan plateau. This remains a truly isolated corner of Nepal, time has stood still here for centuries as inhabitants of Tibetan stock continue to live, cultivate and trade the way they have done for hundreds of years. Most treks into Dolpo take from 14 to 30 days. The best time to trek here is towards the end of the monsoon season Sept to November. Shorter Dolpo reks are possible by flying into the air strip at Jumla. The region offers opportunities to visit ancient villages, high passes, beautiful Lakes, isolated Buddhist monasteries and also to experience the vast array of wildlife inhabiting the region, including Blue sheep, Mountain Goat, Jackal, Wolf and the legendary Snow Leopard. Day by Day Itinerary: Day 01: Arrive Kathmandu, transfer to hotel / tour briefing. Day 02: Sightseeing tour of Kathmandu Valley. Day 03: Fly, Kathmandu / Nepalgunj, overnight hotel Day 04: Early morning, fly to Dolpo (Juphal) then trek to Hanke (2660m) Day 05: Hanke / Samduwa Day 06: Samduwa / Phoksundo Lake (3600m) Day 07: Rest at Phoksundo Lake Day 08: Phoksundo Lake / cross Baga La (5090m) and camp next side Day 09: Baga La / Numla base camp (5190m Day 10: Numla base camp / Chutung Dang (3967m) Day 11: Chutung Dang / Chibu Kharka (3915m) Day 12: -

Jahresbericht 2018 Jahresüberblick 2

Das einfache Schulgebäude war nicht auf starke Regenfälle ausgerichtet und hat den letztjährigen nicht mehr standgehalten. Seit einigen Jahren nehmen Regen- und Schneefälle in den ursprünglich sehr trockenen Gebieten nördlich der Himalayakette zu. Jahresbericht 2018 Jahresüberblick 2. Unsere Projekte im Dolpo 1. Allgemeines zu Upper Dolpo Die Dharma Bhakta Primary School in Namdo/Upper Dolpo und Upper Mustang Anfangs Juli begann die Monsunzeit. Die dies- jährigen starken Regenfälle hinterliessen jedoch Schon im letztjährigen Bericht ist auf die Neu- grosse Schäden an der Infrastruktur. Die Health gliederung des nepalesischen Staatsgebietes in Station sowie das Gewächshaus sind einge- 7 Bundesstaaten hingewiesen worden, die dann stürzt. Die Regenfälle führten aber auch in in verschiedene Verwaltungsbezirke, „Munici- einem Grossteil des Schulgebäudes zu Schäden, palities“ genannt, neu aufgegliedert wurden. die nicht mehr reparierbar sind. Daher fand der Der Verwaltungsbezirk im Dolpo, zu dem die Schulunterricht teilweise im Freien statt. Schule in Namdo gehört, nennt sich „Shey Mit Stolz wurden wir informiert, dass unsere Phoksumdo Rural Municipality“. Er umfasst Schule das erste Schulaustauschprogramm des Teile des Lower wie des Upper Dolpo, das Upper-Dolpo organisierte und durchführte. Ziel Verwaltungszentrum liegt im Upper Dolpo in ist es, dass die Schulen enger zusammenarbei- Saldang. Es führt zu weit, an dieser Stelle auf die ten und Erfahrungen und Ideen ausgetauscht Vor- bzw. Nachteile dieser Grenzziehung bei werden. Die Reaktion auf das 3-tägige Meeting den Verwaltungsbezirken einzugehen. war nur positiv, und fürs 2019 wurde bereits Upper Mustang besteht jetzt aus drei Bezirken: ein neues angesetzt. Der nördlichste unter dem Namen „Lo-Man- Neben dem normalen Schulalltag durften die thang Rural Municipality“ umfasst das Gebiet Kinder der Klassen 3 bis 6 eine 3-tägige Schüler- von Lo-Manthang bis zur Grenze, der Ver- reise unternehmen. -

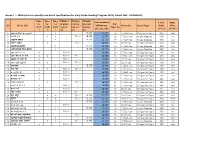

Annex 1 : - Srms Print Run Quantity and Detail Specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts)

Annex 1 : - SRMs print run quantity and detail specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts) Number Number Number Titles Titles Titles Total numbers Cover Inner for for for of print of print of print # of SN Book Title of Print run Book Size Inner Paper Print Print grade grade grade run for run for run for Inner Pg (G1, G2 , G3) (Color) (Color) 1 2 3 G1 G2 G3 1 अनारकल�को अꅍतरकथा x - - 15,775 15,775 24 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 2 अनौठो फल x x - 16,000 15,775 31,775 28 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 3 अमु쥍य उपहार x - - 15,775 15,775 40 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 4 अत� र बु饍�ध x - 16,000 - 16,000 36 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 5 अ쥍छ�को औषधी x - - 15,775 15,775 36 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 6 असी �दनमा �व�व भ्रमण x - - 15,775 15,775 32 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 7 आउ गन� १ २ ३ x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 8 आज मैले के के जान� x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 9 आ굍नो घर राम्रो घर x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 10 आमा खुसी हुनुभयो x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 11 उप配यका x - - 15,775 15,775 20 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4X4 12 ऋतु गीत x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 13 क का �क क� x 16,000 - - 16,000 16 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 14 क दे�ख � स륍म x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 15 कता�तर छौ ? x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 -

Dolpa Juphal Airport

DOLPA JUPHAL AIRPORT Brief Description Dolpa (Juphal) Airport is situated at Juphal Municipality of Dolpa District, Karnali Province. The airport serves as the gate way to Shey- Phoksundo National Park where the Phoksundo Lake is the major attraction. The airport also serves for the means of connection to upper Dolpa Trek which is one of the famous destinations for tourists. General Information Name DOLPA Location Indicator VNDP IATA Code DOP Aerodrome Reference Code 1B Aerodrome Reference Point 285909 N/0824909 E Province/District Karnali/Dolpa Distance and Direction from City Three hours walking Distance from District Headquater( Dunai) Elevation 2503 m. /8212 ft. Off: 977-87690429 Tower: 977-87690429 Contact AFS: VNDPYDYX E-mail: [email protected] 16th Feb to 15th Nov 0600LT-1215LT Operation Hours 16th Nov to 15th Feb 0630LT-1215LT Status Operational Year of Start of Operation 1975 Serviceability All Weather Land Approx. 59659.09 m2 Re-fueling Facility Not Available Service AFIS Type of Traffic Permitted Visual Flight Rule (VFR) Type of Aircraft DHC6, L410, Y12 Schedule Operating Airlines Tara Air, Sita Air, Nepal Airlines, Summit Air Schedule Connectivity Nepalgunj, Surkhet RFF Not Available Infrastructure Condition Airside Runway Type of Surface Bituminous Paved (Asphalt Concrete) Runway Dimension 560 m x 20 m Runway Designation 16/34 Parking Capacity Two DHC6 Types Size of Apron 2400 sq.m. Apron Type Asphalt Concrete Airport Facilities Console One Man Position Tower Console with Associated Equipment and Accessories Communication, -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

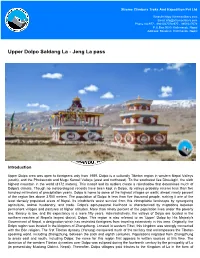

Upper Dolpo Saldang La - Jeng La Pass

Xtreme Climbers Treks And Expedition Pvt Ltd Website:https://xtremeclibers.com Email:[email protected] Phone No:977 - 9801027078,977 - 9851027078 P.O.Box:9080, Kathmandu, Nepal Address: Bansbari, Kathmandu, Nepal Upper Dolpo Saldang La - Jeng La pass Introduction Upper Dolpa area was open to foreigners only from 1989. Dolpo is a culturally Tibetan region in western Nepal Valleys (south), and the Phoksumdo and Mugu Karnali Valleys (west and northwest). To the southwest lies Dhaulagiri, the sixth highest mountain in the world (8172 meters). This massif and its outliers create a rainshadow that determines much of Dolpo's climate. Though no meteorological records have been kept in Dolpo, its valleys probably receive less than five hundred millimeters of precipitation yearly. Dolpo is home to some of the highest villages on earth; almost ninety percent of the region lies above 3,500 meters. The population of Dolpo is less than five thousand people, making it one of the least densely populated areas of Nepal. Its inhabitants wrest survival from this inhospitable landscape by synergizing agriculture, animal husbandry, and trade. Dolpo's agro-pastoral livelihood is characterized by migrations between permanent villages and pastures at higher altitudes. More than ninety percent of the population lives under the poverty line, literacy is low, and life expectancy is a mere fifty years. Administratively, the valleys of Dolpo are located in the northern reaches of Nepal's largest district, Dolpa. This region is also referred to as 'Upper' Dolpo by His Majesty's Government of Nepal, a designation which has restricted foreigners from traveling extensively in this area. -

European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR)

20-1 2001 Double issue EBHR european Bulletin of Himalayan Research The European Bulletin of Himalayan Research is the product of collaboration between academics and researchers with an interest in the Himalayan region in several European countries. It was founded by the late Professor Richard Burghart in 1991 and has appeared twice yearly ever since. It is edited on a rotating basis between Germany, France and the UK. The British editors are: Michael Hutt (Managing Editor), David Gellner, Will Douglas, Ben Campbell (Reviews Editor), Christian McDonaugh, Joanne Moller, Maria Phylactou, Andrew Russell and Surya Subedi. Email: [email protected] Contributing editors are: France: Marie Lecomte-Tilouine, Pascale Dolfus, Anne de Sales Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, UPR 299 7, rue Guy Moquet F-94801 Villejuif cedex email: [email protected] Germany: Martin Gaenszle, Andras Höfer Südasien Institut Universität Heidelberg Im Neuenheimer Feld 330 D-69120 Heidelberg email: [email protected] Switzerland: Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka Ethnologisches Seminar der Universität Zurich Freienstraße 5 CH-8032 Zurich email: [email protected] For subscription information, please consult the EBHR website at dakini.orient.ox.ac.uk/ebhr or contact the publishers directly: Publications Office School of Oriental and African Studies Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square London WC1H 0XG Fax: +44 (0) 20 7962 1577 email: [email protected] ebhr SOAS • London CNRS • Paris SAI • HEIdelberg ISSN 0943 8254 EBHR 20-1 • 2001 Double issue ARTICLES Life-Journeys: Rai ritual healers’ narratives on their callings Martin Gaenszle 9 The Construction of Personhood: Two life stories from Garhwal Antje Linkenbach 23 Protecting the Treasures of the Earth: Nominating Dolpo as a World Heritage site Terence Hay-Edie 46 On the Relationship Between Folk and Classical Traditions in South Asia Claus Peter Zoller 77 Sliding Downhill: Some reflections on thirty years of change in a Himalayan village Alan Macfarlane 105 — with responses from Ben Campbell, Kul B. -

Nomads of Dolpo

V I S I T N AT I O N A LG E O G R A P H I C .O RG C H A N G I N G P L A N E T Nomads of Dolpo In Changing Planet July 12, 2015 0 Comments Joanna Eede It is one of the last nomadic trading caravans in the world. For more than a thousand years, the Dolpo-pa people of Nepal have depended for their survival on a biannual journey across the Himalayas. Once the summer harvest is over, the people of Dolpo sew flags and red pommels into the ears of their yaks, rub butter on their horns and throw barley seeds to the cold wind. Then they leave the fertile middle hills of their homeland and head north, to the plateaux of Tibet, where they carry out an ancient trade with their Tibetan neighbours. Dolpo is a wild, mountainous region in the far western reaches of Nepal. Once part of the ancient Zhang Zhung kingdom, it claims some of the highest inhabited villages on earth. There are no roads and no electricity; access is by small plane or several days’ trek over high passes. Fierce winter snowstorms ensure that these routes are impassable for up to six months of the year, when Dolpo is isolated from the rest of the country. But during the summer months, when the alpine fields are alive with yellow poppies and the lower slopes are furrowed with barley and buckwheat, the paths are navigable again. Dolpo is beautiful, remote and culturally fascinating, but it is also one of the poorest areas in Nepal. -

Biodiversity in Karnali Province: Current Status and Conservation

Biodiversity in Karnali Province: Current Status and Conservation Karnali Province Government Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment Surkhet, Nepal Biodiversity in Karnali Province: Current Status and Conservation Karnali Province Government Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment Surkhet, Nepal Copyright: © 2020 Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment, Karnali Province Government, Surkhet, Nepal The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of Ministry of Tourism, Forest and Environment, Karnali Province Government, Surkhet, Nepal Editors: Krishna Prasad Acharya, PhD and Prakash K. Paudel, PhD Technical Team: Achyut Tiwari, PhD, Jiban Poudel, PhD, Kiran Thapa Magar, Yogendra Poudel, Sher Bahadur Shrestha, Rajendra Basukala, Sher Bahadur Rokaya, Himalaya Saud, Niraj Shrestha, Tejendra Rawal Production Editors: Prakash Basnet and Anju Chaudhary Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Acharya, K. P., Paudel, P. K. (2020). Biodiversity in Karnali Province: Current Status and Conservation. Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment, Karnali Province Government, Surkhet, Nepal Cover photograph: Tibetan wild ass in Limi valley © Tashi R. Ghale Keywords: biodiversity, conservation, Karnali province, people-wildlife nexus, biodiversity profile Editors’ Note Gyau Khola Valley, Upper Humla © Geraldine Werhahn This book “Biodiversity in Karnali Province: Current Status and Conservation”, is prepared to consolidate existing knowledge about the state of biodiversity in Karnali province. The book presents interrelated dynamics of society, physical environment, flora and fauna that have implications for biodiversity conservation. -

Sey Phoksundo

Safety Precautions Park Regulations to follow or High altitude sickness can affect you if elevation is gained too things to remember rapidly and without proper acclimatization. The symptoms are -headache, difficulty in sleeping, breathlessness, loss of appetite • An entry fee of Rs. 3,000 (Foreigners), Rs. 1,500 (SAARC and general fatigue. If someone develops the symptoms, stop Nationals), Rs. 100 (Nepali) visitor and Rs. 25 for tourist ascending immediately. If symptoms persist, the only proven cure porter should be paid at designated ticket counter. is to descend to a lower elevation. • Valid entry permits are available from the National Parks Trekking Routes ticket counter at the Nepal Tourism Board, Bhrikuti Mandap, Entire Dolpa district is divided into two regions i.e. lower and Kathmandu or park entrance gate at Suligad. upper. The upper limit of lower Dolpa is up-to Phoksundo Lake of • The entry permit is non-refundable, non-transferable and is Phoksundo rural municipality. An individual trekking is permitted for a single entry only. to trekking up-to Phoksundo Lake. The trans-Himalayan region, which lies at upper Dolpa, is restricted to trekking. A group • Entering the park without a permit is illegal. Park personnel trekking permission can be issued only through the recognized may ask for the permit, so visitors are requested to keep the trekking agency of Nepal. permit with them. • Get special permit for documentary/filming from the http//:www.dnpwc.gov.np How to get the Park Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation One of the following gateways can be mapped out to visit SPNP: (DNPWC).