European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Generated By

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Dec 07 2015, NEWGEN 3 Vajrayāna Traditions in Nepal Todd Lewis and Naresh Man Bajracarya Introduction The existence of tantric traditions in the Kathmandu Valley dates back at least a thousand years and has been integral to the Hindu– Buddhist civi- lization of the Newars, its indigenous people, until the present day. This chapter introduces what is known about the history of the tantric Buddhist tradition there, then presents an analysis of its development in the pre- modern era during the Malla period (1200–1768 ce), and then charts changes under Shah rule (1769–2007). We then sketch Newar Vajrayāna Buddhism’s current characteristics, its leading tantric masters,1 and efforts in recent decades to revitalize it among Newar practitioners. This portrait,2 especially its history of Newar Buddhism, cannot yet be more than tentative in many places, since scholarship has not even adequately documented the textual and epigraphic sources, much less analyzed them systematically.3 The epigraphic record includes over a thousand inscrip- tions, the earliest dating back to 464 ce, tens of thousands of manuscripts, the earliest dating back to 998 ce, as well as the myriad cultural traditions related to them, from art and architecture, to music and ritual. The religious traditions still practiced by the Newars of the Kathmandu Valley represent a unique, continuing survival of Indic religions, including Mahāyāna- Vajrayāna forms of Buddhism (Lienhard 1984; Gellner 1992). Rivaling in historical importance the Sanskrit texts in Nepal’s libraries that informed the Western “discovery” of Buddhism in the nineteenth century (Hodgson 1868; Levi 1905– 1908; Locke 1980, 1985), Newar Vajrayāna acprof-9780199763689.indd 872C28B.1F1 Master Template has been finalized on 19- 02- 2015 12/7/2015 6:28:54 PM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Dec 07 2015, NEWGEN 88 TanTric TradiTions in Transmission and TranslaTion tradition in the Kathmandu Valley preserves a rich legacy of vernacular texts, rituals, and institutions. -

Upper Dolpo Trek - 26 Days

Upper Dolpo Trek - 26 days Go on 26 days trip for $ per person Trekking in the Dolpo region has only been permitted since mid-1989. The region lies to the west of the Kali Gandaki Valley, Dolpo is located inside the Shey-Phoksundo National Park in mid-western Nepal, behind the Dhaulagiri massif, towards the Tibetan plateau. This remains a truly isolated corner of Nepal, time has stood still here for centuries as inhabitants of Tibetan stock continue to live, cultivate and trade the way they have done for hundreds of years. Most treks into Dolpo take from 14 to 30 days. The best time to trek here is towards the end of the monsoon season Sept to November. Shorter Dolpo reks are possible by flying into the air strip at Jumla. The region offers opportunities to visit ancient villages, high passes, beautiful Lakes, isolated Buddhist monasteries and also to experience the vast array of wildlife inhabiting the region, including Blue sheep, Mountain Goat, Jackal, Wolf and the legendary Snow Leopard. Day by Day Itinerary: Day 01: Arrive Kathmandu, transfer to hotel / tour briefing. Day 02: Sightseeing tour of Kathmandu Valley. Day 03: Fly, Kathmandu / Nepalgunj, overnight hotel Day 04: Early morning, fly to Dolpo (Juphal) then trek to Hanke (2660m) Day 05: Hanke / Samduwa Day 06: Samduwa / Phoksundo Lake (3600m) Day 07: Rest at Phoksundo Lake Day 08: Phoksundo Lake / cross Baga La (5090m) and camp next side Day 09: Baga La / Numla base camp (5190m Day 10: Numla base camp / Chutung Dang (3967m) Day 11: Chutung Dang / Chibu Kharka (3915m) Day 12: -

Jahresbericht 2018 Jahresüberblick 2

Das einfache Schulgebäude war nicht auf starke Regenfälle ausgerichtet und hat den letztjährigen nicht mehr standgehalten. Seit einigen Jahren nehmen Regen- und Schneefälle in den ursprünglich sehr trockenen Gebieten nördlich der Himalayakette zu. Jahresbericht 2018 Jahresüberblick 2. Unsere Projekte im Dolpo 1. Allgemeines zu Upper Dolpo Die Dharma Bhakta Primary School in Namdo/Upper Dolpo und Upper Mustang Anfangs Juli begann die Monsunzeit. Die dies- jährigen starken Regenfälle hinterliessen jedoch Schon im letztjährigen Bericht ist auf die Neu- grosse Schäden an der Infrastruktur. Die Health gliederung des nepalesischen Staatsgebietes in Station sowie das Gewächshaus sind einge- 7 Bundesstaaten hingewiesen worden, die dann stürzt. Die Regenfälle führten aber auch in in verschiedene Verwaltungsbezirke, „Munici- einem Grossteil des Schulgebäudes zu Schäden, palities“ genannt, neu aufgegliedert wurden. die nicht mehr reparierbar sind. Daher fand der Der Verwaltungsbezirk im Dolpo, zu dem die Schulunterricht teilweise im Freien statt. Schule in Namdo gehört, nennt sich „Shey Mit Stolz wurden wir informiert, dass unsere Phoksumdo Rural Municipality“. Er umfasst Schule das erste Schulaustauschprogramm des Teile des Lower wie des Upper Dolpo, das Upper-Dolpo organisierte und durchführte. Ziel Verwaltungszentrum liegt im Upper Dolpo in ist es, dass die Schulen enger zusammenarbei- Saldang. Es führt zu weit, an dieser Stelle auf die ten und Erfahrungen und Ideen ausgetauscht Vor- bzw. Nachteile dieser Grenzziehung bei werden. Die Reaktion auf das 3-tägige Meeting den Verwaltungsbezirken einzugehen. war nur positiv, und fürs 2019 wurde bereits Upper Mustang besteht jetzt aus drei Bezirken: ein neues angesetzt. Der nördlichste unter dem Namen „Lo-Man- Neben dem normalen Schulalltag durften die thang Rural Municipality“ umfasst das Gebiet Kinder der Klassen 3 bis 6 eine 3-tägige Schüler- von Lo-Manthang bis zur Grenze, der Ver- reise unternehmen. -

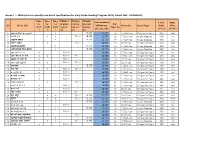

Annex 1 : - Srms Print Run Quantity and Detail Specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts)

Annex 1 : - SRMs print run quantity and detail specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts) Number Number Number Titles Titles Titles Total numbers Cover Inner for for for of print of print of print # of SN Book Title of Print run Book Size Inner Paper Print Print grade grade grade run for run for run for Inner Pg (G1, G2 , G3) (Color) (Color) 1 2 3 G1 G2 G3 1 अनारकल�को अꅍतरकथा x - - 15,775 15,775 24 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 2 अनौठो फल x x - 16,000 15,775 31,775 28 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 3 अमु쥍य उपहार x - - 15,775 15,775 40 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 4 अत� र बु饍�ध x - 16,000 - 16,000 36 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 5 अ쥍छ�को औषधी x - - 15,775 15,775 36 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 6 असी �दनमा �व�व भ्रमण x - - 15,775 15,775 32 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 7 आउ गन� १ २ ३ x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 8 आज मैले के के जान� x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 9 आ굍नो घर राम्रो घर x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 10 आमा खुसी हुनुभयो x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 11 उप配यका x - - 15,775 15,775 20 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4X4 12 ऋतु गीत x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 13 क का �क क� x 16,000 - - 16,000 16 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 14 क दे�ख � स륍म x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 15 कता�तर छौ ? x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 -

History, Anthropology and the Study of Communities: Some Problems in Macfarlane's Proposal

C. J. Calhoun History, anthropology and the study of communities: some problems in Macfarlanes proposal' In a recent paper, Alan Macfarlane advertises a new approach to the study of communities in which 'a combination of the anthropological techniques and the historical material could be extremely fruitful'.2 Unfortunately, he fails to make clear just what the approach he advocates is, and with what problems and phenomena it is intended to deal. He thus exacerbates rather than solves the methodological and conceptual problems which face social historians who would study community. The present paper is primarily polemical in intention. It is in agreement that community can be the object of coherent and productive study by historians and social scientists, working together and/or drawing on the products of each other's labours. It argues, however, that Macfarlane's conceptual apparatus is seriously problematic, and does not constitute a coherent approach. I have outlined elsewhere what I consider to be such a coherent approach.3 It makes community a comparative and historical variable. Macfarlane dismisses the concept as meaningless at the beginning of his paper, but then finds it necessary to reintroduce it in quotation marks in the latter part - without ever defining it. He introduces several potentially useful anthropological concepts, but vitiates their value by both a misleading treatment and the implication that they are replacements for, rather than supplements to, the concept of community. In the following I attempt to give a more accurate background to and interpretation of these concepts, and to correct several logical and methodological errors in Macfarlane's presentation. -

Upper Dolpo Saldang La - Jeng La Pass

Xtreme Climbers Treks And Expedition Pvt Ltd Website:https://xtremeclibers.com Email:[email protected] Phone No:977 - 9801027078,977 - 9851027078 P.O.Box:9080, Kathmandu, Nepal Address: Bansbari, Kathmandu, Nepal Upper Dolpo Saldang La - Jeng La pass Introduction Upper Dolpa area was open to foreigners only from 1989. Dolpo is a culturally Tibetan region in western Nepal Valleys (south), and the Phoksumdo and Mugu Karnali Valleys (west and northwest). To the southwest lies Dhaulagiri, the sixth highest mountain in the world (8172 meters). This massif and its outliers create a rainshadow that determines much of Dolpo's climate. Though no meteorological records have been kept in Dolpo, its valleys probably receive less than five hundred millimeters of precipitation yearly. Dolpo is home to some of the highest villages on earth; almost ninety percent of the region lies above 3,500 meters. The population of Dolpo is less than five thousand people, making it one of the least densely populated areas of Nepal. Its inhabitants wrest survival from this inhospitable landscape by synergizing agriculture, animal husbandry, and trade. Dolpo's agro-pastoral livelihood is characterized by migrations between permanent villages and pastures at higher altitudes. More than ninety percent of the population lives under the poverty line, literacy is low, and life expectancy is a mere fifty years. Administratively, the valleys of Dolpo are located in the northern reaches of Nepal's largest district, Dolpa. This region is also referred to as 'Upper' Dolpo by His Majesty's Government of Nepal, a designation which has restricted foreigners from traveling extensively in this area. -

The Thangmi of Nepal and India Sara Shneiderman, Mark Turin

Revisiting ethnography, recognizing a forgotten people: The Thangmi of Nepal and India Sara Shneiderman, Mark Turin To cite this version: Sara Shneiderman, Mark Turin. Revisiting ethnography, recognizing a forgotten people: The Thangmi of Nepal and India. Studies in Nepali History and Society, Mandala Book Point, 2006, 11 (1), pp.97- 181. halshs-03083422 HAL Id: halshs-03083422 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03083422 Submitted on 27 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 96 Celayne Heaton Shrestha Onta, Pratyoush. 1996'1. Ambivalence Denied: The Making of Ra~triya Itihas in REVISITING ETHNOGRAPHY, RECOGNIZING Panchayat Era Textbooks. Contrihutions to Nepalese Studies 23(1): 213 254. AFORGOTTEN PEOPLE: THE THANGMI OF Onta, Pratyoush. 1996b. Creating a Brave Nepali Nation in British India: the NEPAL AND INDIA Rhetoric of Jati Improvement, Rediscovery of Bhanubhakta, and the Writing of Blr History. Studies in Nepali Historv and Society I(I): 37-76. Sara Shneiderman and Mark Turin Onta, Pratyoush. 1997. Activities in a 'Fossil State': Balkrishna Sarna and the Improvisation of Nepali Identity. Studies in Nepali History and Society 2(\): 69-102. There is no idea about the origin of the Thami communitv or the term Perera, Jehan. -

Visual Anthropology

ENCOUNTER WITH VISUAL ANTHROPOLOGY Sarah Harrison and Alan Macfarlane 1 Contents Preface to the Series 3 How to view films and technical information 4 Introduction 5 Peter Loizos 14 September 2002 8 Paul Hockings 11 November 2005 12 Gary Kildea 3 November 2006 19 David MacDougall 29-30 June 2007 24 Karl Heider 30 June 2007 38 Liang Bibo 28 July 2008 46 Appendices 1. Early Ethnographic filming in Britain 52 2. Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf 61 Other possible volumes 81 Acknowledgements and royalties 82 © Sarah Harrison and Alan Macfarlane 2014 2 Preface to the series There have been many autobiographical accounts of the creative process. These tend to concentrate on one level, and within that one aspect, the cerebral, intellectual working of a single thinker or artist’s mind. Yet if we are really to understand what the conditions are for a really creative and fulfilling life we need to understand the process at five levels. At the widest, there is the level of civilizations, some of which encourage personal creativity, while others dampen it. Then there are institutions such as a university, which encourage the individual or stifle him or her. Then there are personal networks; all thinkers work with others whether they acknowledge it or not. Then there is the level of the individual, his or her character and mind. Finally there is an element of chance or random variation. I have long been interested in these inter-acting levels and since 1982 I have been filming people talking about their life and work. In these interviews, characteristically lasting one to two hours, I have paid particular attention to the family life, childhood, education and friendships which influence us. -

Nomads of Dolpo

V I S I T N AT I O N A LG E O G R A P H I C .O RG C H A N G I N G P L A N E T Nomads of Dolpo In Changing Planet July 12, 2015 0 Comments Joanna Eede It is one of the last nomadic trading caravans in the world. For more than a thousand years, the Dolpo-pa people of Nepal have depended for their survival on a biannual journey across the Himalayas. Once the summer harvest is over, the people of Dolpo sew flags and red pommels into the ears of their yaks, rub butter on their horns and throw barley seeds to the cold wind. Then they leave the fertile middle hills of their homeland and head north, to the plateaux of Tibet, where they carry out an ancient trade with their Tibetan neighbours. Dolpo is a wild, mountainous region in the far western reaches of Nepal. Once part of the ancient Zhang Zhung kingdom, it claims some of the highest inhabited villages on earth. There are no roads and no electricity; access is by small plane or several days’ trek over high passes. Fierce winter snowstorms ensure that these routes are impassable for up to six months of the year, when Dolpo is isolated from the rest of the country. But during the summer months, when the alpine fields are alive with yellow poppies and the lower slopes are furrowed with barley and buckwheat, the paths are navigable again. Dolpo is beautiful, remote and culturally fascinating, but it is also one of the poorest areas in Nepal. -

Hindu and Buddhist Initiations in India and Nepal Edited by Astrid Zotter and Christof Zotter

Hindu and Buddhist Initiations in India and Nepal Edited by Astrid Zotter and Christof Zotter 2010 Harrassowitz Verlag . Wiesbaden ISSN 1860-2053 ISBN 978-3-447-06387-6 Todd T. Lewis Ritual (Re-)Constructions of Personal Identity: Newar Buddhist Life-Cycle Rites and Identity among the Urāy of Kathmandu Introduction – Buddhist tradition and ritual Among contemporary Buddhists in both the Euro-American world and Asia, the very notion that ritual is formative of Buddhist identity, or could engender a transformative spiritual experience, is seen as outdated or even absurd. What is worthy in this tradi- tion, in this view, is the legacy of individual meditation practices passed down from its spiritual virtuosi and the fearless parsing of reality by its extraordinary sage-scholars. Most of the equally ancient daily and lifelong ritual practices in each regional forma- tion of Buddhism are destined to fade away. In this “Protestant Buddhist” perspective (Gombrich & Obeyesekere 1988; Schopen 1991), there is little to mourn from the exci- sion of superstitions, rituals, and habits that developed in previous centuries at Buddhist monasteries and temples, in towns and villages, and in families; since most people do not know the rationale of these religious acts, the exact meanings of the words they ut- ter or have uttered on their behalf, this modernist reduction of Buddhist tradition to its “true essence” is positive, even necessary. If in the past being a Buddhist entailed much more than sitting in meditation and joining in discourse on the intricacies of doctrine, the modern Buddhist no longer needs to carry on this vestigial baggage. -

Shweta Shardul

SHWETA SHARDUL A Multidisciplinary Journal Volume XVII, Issue 1, Year 2020 ISSN 2631-2255 Peer-Reviewed Open Access MADAN BHANDARI MEMORIAL COLLEGE Research Management Cell PO Box: 5640, New Baneshwor, Kathmandu Phone: 015172175/5172682 Email: [email protected]; Website: www.mbmc.edu.np SHWETA SHARDUL: A Multidisciplinary Journal (SSMJ) is a peer-reviewed and open access multidisciplinary journal, published in print on the annual basis. This journal is an excellent platform for publication of all kinds of scholarly research articles on multidisciplinary areas. Published by : Madan Bhandari Memorial College Research Management Cell PO Box: 5640, New Baneshwor, Kathmandu Phone: 015172175/5172682 Email: [email protected]; Website: www.mbmc.edu.np Editors : Hari Bahadur Chand Kamal Neupane Niruja Phuyal Copyright 2020/2077 © : The Publisher Print ISSN : 2631-2255 Print Copies : 500 Disclaimer The views expressed in the articles are exclusively those of individual authors. The editors and publisher are not responsible for any controversy and/or adverse effects from the publication of the articles. Computer Layout : Samriddhi Designing House Naxal, Chardhunge-01 9841634975 Printed at : Nepal Table of Contents Topics Contributors Page No. English Literature Visual Rhetoric in Contemporary Mithila ... Santosh Kumar Singh, PhD 3 Revisiting English History in J.K. ... Shankar Subedi 26 Buddhist Ideology in T. S. Eliot’s Poetry ... Raj Kishor Singh, PhD 37 Hailing the Individual in Marquez’s No ... Gol Man Gurung, PhD 62 Reasserting Female Subjectivity in Rich’s ... Pradip Sharma 78 Nepali Literature l;l4r/0f >]i7sf k|f/lDes r/0fsf sljtfdf === 8f= km0fLGb|/fh lg/f}nf 93 dfofn' x'Dnf lgofqfs[ltdf kof{j/0f x]daxfb'/ e08f/L 119 Anthropology Ruprekha Maharjan, PhD Newari Divine Marriage: Ihi and Barhah .. -

'The Group and the Individual in History', Alan Macfarlane [From: Space, Hierarchy and Society: Interdisciplinary Studies In

‘The Group and the Individual in History’, Alan Macfarlane [From: Space, Hierarchy and Society: Interdisciplinary Studies in Social Area Analysis, eds. Barry C.Burnham and John Kingsbury, BAR International Series 59 (1979)] p.17 ABSTRACT Social scientists have suggested two contrasted models of human societies, those based on the 'group' and those on the 'individual'. Peasant and tribal societies are examples of the former, Hunter-Gatherers and modern post- industrial societies of the latter. In the former, the important boundaries are between large units-clans, castes, villages etc. In the latter, the boundaries are between the individual self and the outside world. The major theories of sociology suggest a change from group to individual (De Tocqueville, Riesman). The change is expressed and caused by many other changes: from status to contract (Maine), from community to Society (Tönnies), from peasant/feudal to capitalist (Marx, Weber), from hierarchy to equality (Dumont). In many of these theories the turning point has been either the industrial /urban revolution of the C18-19, or the earlier Protestant/Capitalist revolution of the C16-C17. But all the theories see societies moving along an evolutionary trail from a. to b. This paper will consider the proposition that this is an oversimplification and that while some societies move in this way, others remain predominantly of the 'group' or 'individual' based kind for all of recorded time. Since England has, above all, been taken as an example of the transition from group to individual in the writings of Maine, Marx, Weber, Tönnies, De Tocqueville and others, the paper will provide a very brief examination of the history of England from the thirteenth to eighteenth centuries.