Diversity of Judaism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Major Branches of Modern Judaism May 10, 2012

Understanding the Major Branches of Modern Judaism May 10, 2012 Initial terms: 24 or 72 kinds Torah/Talmud (oral/written law).Halacha orthopraxy/orthodoxy, haskalah Babylonian Talmud kabbalah, Sephardic, Ashkenazi (with material gleaned from Wikipedia articles- no access to my books yet) Modern Judaism is loosely broken into three main branches: Orthodox Judaism is the approach to Judaism which adheres to the traditional interpretation and application of the laws and ethics of the Torah as legislated in the Talmudic texts by the Sanhedrin ("Oral Torah") and subsequently developed and applied by the later authorities known as the Gaonim, Rishonim, and Acharonim. Orthodox Jews are also called "observant Jews"; Orthodoxy is known also as "Torah Judaism" or "traditional Judaism". Orthodox Judaism generally refers to Modern Orthodox Judaism and Haredi Judaism (Chasidic Chabad) but can actually include a wide range of beliefs. Orthodoxy collectively considers itself the only true heir to the Jewish tradition. The Orthodox Jewish movements generally consider all non-Orthodox Jewish movements to be unacceptable deviations from authentic Judaism; both because of other denominations' doubt concerning the verbal revelation of Written and Oral Torah, and because of their rejection of Halakhic precedent as binding. As such, Orthodox groups characterize non-Orthodox forms of Judaism as heretical Reform Judaism is a phrase that refers to various beliefs, practices and organizations associated with the Reform Jewish movement in North America, the United Kingdom and elsewhere.[1] In general, Reform Judaism maintains that Judaism and Jewish traditions should be modernized and compatible with participation in the surrounding culture. Many branches of Reform Judaism hold that Jewish law should be interpreted as a set of general guidelines rather than as a list of restrictions whose literal observance is required of all Jews.[2][3] Similar movements that are also occasionally called "Reform" include the Israeli Progressive Movement and its worldwide counterpart. -

M E O R O T a Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (Formerly Edah Journal)

M e o r o t A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly Edah Journal) Tishrei 5770 Special Edition on Modern Orthodox Education CONTENTS Editor’s Introduction to Special Tishrei 5770 Edition Nathaniel Helfgot SYMPOSIUM On Modern Orthodox Day School Education Scot A. Berman, Todd Berman, Shlomo (Myles) Brody, Yitzchak Etshalom,Yoel Finkelman, David Flatto Zvi Grumet, Naftali Harcsztark, Rivka Kahan, Miriam Reisler, Jeremy Savitsky ARTICLES What Should a Yeshiva High School Graduate Know, Value and Be Able to Do? Moshe Sokolow Responses by Jack Bieler, Yaakov Blau, Erica Brown, Aaron Frank, Mark Gottlieb The Economics of Jewish Education The Tuition Hole: How We Dug It and How to Begin Digging Out of It Allen Friedman The Economic Crisis and Jewish Education Saul Zucker Striving for Cognitive Excellence Jack Nahmod To Teach Tsni’ut with Tsni’ut Meorot 7:2 Tishrei 5770 Tamar Biala A Publication of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah REVIEW ESSAY Rabbinical School © 2009 Life Values and Intimacy Education: Health Education for the Jewish School, Yocheved Debow and Anna Woloski-Wruble, eds. Jeffrey Kobrin STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Meorot: A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly The Edah Journal) Statement of Purpose Meorot is a forum for discussion of Orthodox Judaism’s engagement with modernity, published by Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School. It is the conviction of Meorot that this discourse is vital to nurturing the spiritual and religious experiences of Modern Orthodox Jews. Committed to the norms of halakhah and Torah, Meorot is dedicated -

1 Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos

Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos: Some Tentative Thoughts David Berger The deep and systemic tension between contemporary egalitarianism and many authoritative Jewish texts about gentiles takes varying forms. Most Orthodox Jews remain untroubled by some aspects of this tension, understanding that Judaism’s affirmation of chosenness and hierarchy can inspire and ennoble without denigrating others. In other instances, affirmations of metaphysical differences between Jews and gentiles can take a form that makes many of us uncomfortable, but we have the legitimate option of regarding them as non-authoritative. Finally and most disturbing, there are positions affirmed by standard halakhic sources from the Talmud to the Shulhan Arukh that apparently stand in stark contrast to values taken for granted in the modern West and taught in other sections of the Torah itself. Let me begin with a few brief observations about the first two categories and proceed to somewhat more extended ruminations about the third. Critics ranging from medieval Christians to Mordecai Kaplan have directed withering fire at the doctrine of the chosenness of Israel. Nonetheless, if we examine an overarching pattern in the earliest chapters of the Torah, we discover, I believe, that this choice emerges in a universalist context. The famous statement in the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 4:5) that Adam was created singly so that no one would be able to say, “My father is greater than yours” underscores the universality of the original divine intent. While we can never know the purpose of creation, one plausible objective in light of the narrative in Genesis is the opportunity to actualize the values of justice and lovingkindness through the behavior of creatures who subordinate themselves to the will 1 of God. -

Print Friendly Version

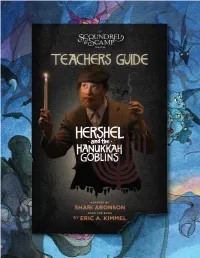

TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 The Holiday of Hanukkah 5 Judaism and the Jewish Diaspora 8 Ashkenazi Jews and Yiddish 9 Latkes! 10 Pickles! 11 Body Mapping 12 Becoming the Light 13 The Nigun 14 Reflections with Playwright Shari Aronson 15 Interview with Author Eric Kimmel 17 Glossary 18 Bibliography Using the Guide Welcome, Teachers! This guide is intended as a supplement to the Scoundrel and Scamp’s production of Hershel & The Hanukkah Goblins. Please note that words bolded in the guide are vocabulary that are listed and defined at the end of the guide. 2 Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins Teachers Guide | The Scoundrel & Scamp Theatre The Holiday of Hanukkah Introduction to Hanukkah Questions: In Hebrew, the word Hanukkah means inauguration, dedication, 1. What comes to your mind first or consecration. It is a less important Jewish holiday than others, when you think about Hanukkah? but has become popular over the years because of its proximity to Christmas which has influenced some aspects of the holiday. 2. Have you ever participated in a Hanukkah tells the story of a military victory and the miracle that Hanukkah celebration? What do happened more than 2,000 years ago in the province of Judea, you remember the most about it? now known as Palestine. At that time, Jews were forced to give up the study of the Torah, their holy book, under the threat of death 3. It is traditional on Hanukkah to as their synagogues were taken over and destroyed. A group of eat cheese and foods fried in oil. fighters resisted and defeated this army, cleaned and took back Do you eat cheese or fried foods? their synagogue, and re-lit the menorah (a ceremonial lamp) with If so, what are your favorite kinds? oil that should have only lasted for one night but that lasted for eight nights instead. -

A Fresh Perspective on the History of Hasidic Judaism

eSharp Issue 20: New Horizons A Fresh Perspective on the History of Hasidic Judaism Eva van Loenen (University of Southampton) Introduction In this article, I shall examine the history of Hasidic Judaism, a mystical,1 ultra-orthodox2 branch of Judaism, which values joyfully worshipping God’s presence in nature as highly as the strict observance of the laws of Torah3 and Talmud.4 In spite of being understudied, the history of Hasidic Judaism has divided historians until today. Indeed, Hasidic Jewish history is not one monolithic, clear-cut, straightforward chronicle. Rather, each scholar has created his own narrative and each one is as different as its author. While a brief introduction such as this cannot enter into all the myriad divergences and similarities between these stories, what I will attempt to do here is to incorporate and compare an array of different views in order to summarise the history of Hasidism and provide a more objective analysis, which has not yet been undertaken. Furthermore, my historical introduction in Hasidic Judaism will exemplify how mystical branches of mainstream religions might develop and shed light on an under-researched division of Judaism. The main focus of 1 Mystical movements strive for a personal experience of God or of his presence and values intuitive, spiritual insight or revelationary knowledge. The knowledge gained is generally ‘esoteric’ (‘within’ or hidden), leading to the term ‘esotericism’ as opposed to exoteric, based on the external reality which can be attested by anyone. 2 Ultra-orthodox Jews adhere most strictly to Jewish law as the holy word of God, delivered perfectly and completely to Moses on Mount Sinai. -

We Arrived in Manipur Unannounced, to Get a Bona Fide Glimpse Into How

ESENT I PR AR D N A To see our subscription options, I R please click on the Mishpacha tab A e knocked and waited nervously mesor ah because we hadn’t notified them ahead — yet we weren’t disappointed. Quest As the door opened to the little hut, a kippah-clad man smiled broadly and Wsaid, “Baruch haba!” He led us through a courtyard to a small, well-kept synagogue. We were not in Monsey, but in a far-fl ung corner of India on the northeastern border state of Manipur, preparing the ground in advance of our curious delegation — a party of 35 Western Jews and one of the rare groups to visit this little-known Indian com- munity known as the Bnei Menashe. We were both excited and relieved by the warm wel- come, as their story is exotic and spans thousands of years of Jewish history. It is a direct link with our Biblical past and raises interesting halachic and philosophic conun- drums about our future. Welcome to our search for part of the Ten Lost Tribes. It all started with a call from the OU Israel Center in- viting us to lead a “Halachic Adventure” tour. We asked the organizers where they would like to go, and they re- plied, “Where would you like to lead us?” The answer for us was simple: to return to India where the richness and diversity of Jewish history is largely unknown to much of the Jewish world. Our goal was to give our fellow adventurers a unique, exciting, and o -the-beaten-track experience. -

Migration of Jews to Palestine in the 20Th Century

Name Date Migration of Jews to Palestine in the 20th Century Read the text below. The Jewish people historically defined themselves as the Jewish Diaspora, a group of people living in exile. Their traditional homeland was Palestine, a geographic region on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Jewish leaders trace the source of the Jewish Diaspora to the Roman occupation of Palestine (then called Judea) in the 1st century CE. Fleeing the occupation, most Jews immigrated to Europe. Over the centuries, Jews began to slowly immigrate back to Palestine. Beginning in the 1200s, Jewish people were expelled from England, France, and central Europe. Most resettled in Russia and Eastern Europe, mainly Poland. A small population, however, immigrated to Palestine. In 1492, when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella expelled all Jewish people living in Spain, some refugees settled in Palestine. At the turn of the 20th century, European Jews were migrating to Palestine in large numbers, fleeing religious persecution. In Russia, Jewish people were segregated into an area along the country’s western border, called the Pale of Settlement. In 1881, Russians began mass killings of Jews. The mass killings, called pogroms, caused many Jews to flee Russia and settle in Palestine. Prejudice against Jews, called anti-Semitism, was very strong in Germany, Austria-Hungary, and France. In 1894, a French army officer named Alfred Dreyfus was falsely accused of treason against the French government. Dreyfus, who was Jewish, was imprisoned for five years and tried again even after new information proved his innocence. The incident, called The Dreyfus Affair, exposed widespread anti-Semitism in Western Europe. -

The Hebrew-Jewish Disconnection

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Master’s Theses and Projects College of Graduate Studies 5-2016 The eH brew-Jewish Disconnection Jacey Peers Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses Part of the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Peers, Jacey. (2016). The eH brew-Jewish Disconnection. In BSU Master’s Theses and Projects. Item 32. Available at http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses/32 Copyright © 2016 Jacey Peers This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. THE HEBREW-JEWISH DISCONNECTION Submitted by Jacey Peers Department of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages Bridgewater State University Spring 2016 Content and Style Approved By: ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Joyce Rain Anderson, Chair of Thesis Committee Date ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Anne Doyle, Committee Member Date ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Julia (Yulia) Stakhnevich, Committee Member Date 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my mom for her support throughout all of my academic endeavors; even when she was only half listening, she was always there for me. I truly could not have done any of this without you. To my dad, who converted to Judaism at 56, thank you for showing me that being Jewish is more than having a certain blood that runs through your veins, and that there is hope for me to feel like I belong in the community I was born into, but have always felt next to. -

From Falashas to Ethiopian Jews

FROM FALASHAS TO ETHIOPIAN JEWS: THE EXTERNAL INFLUENCES FOR CHANGE C. 1860-1960 BY DANIEL P. SUMMERFIELD A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON (SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES) FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PhD) 1997 ProQuest Number: 10673074 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673074 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT The arrival of a Protestant mission in Ethiopia during the 1850s marks a turning point in the history of the Falashas. Up until this point, they lived relatively isolated in the country, unaffected and unaware of the existence of world Jewry. Following this period and especially from the beginning of the twentieth century, the attention of certain Jewish individuals and organisations was drawn to the Falashas. This contact initiated a period of external interference which would ultimately transform the Falashas, an Ethiopian phenomenon, into Ethiopian Jews, whose culture, religion and identity became increasingly connected with that of world Jewry. It is the purpose of this thesis to examine the external influences that implemented and continued the process of transformation in Falasha society which culminated in their eventual emigration to Israel. -

The Hebrew Revolution and the Revolution of the Hebrew Language Between the 1880S and the 1930S

The Hebrew Revolution and the Revolution of the Hebrew Language between the 1880s and the 1930s Judith Winther Copenhagen The new Hebrew culture which began to crys- Eliezer Ben Yehudah was born in 1858, tallize in the land of Israel from the end of the Ben Gurion in 1886, and Berl Kazenelson in last century, is a successful event of "cultural 1887. planning". During a relatively short period of As a man who was not active in the so- time a little group of"culture planners" succee- cialist Jewish movement Ben Yehudah's dedi- ded in creating a system which in a significant cation to Hebrew is probably comprehensible. way was adapted to the requested Zionist ide- But why should a prominent socialist like Berl ology. The fact that the means by which the Kazenelson stick to the spoken Hebrew langu- "cultural planning" was realized implicated a age? A man, who prior to his immigration to heroic presentation of the happenings that led Palestine was an anti-Zionist, ridiculed Hebrew to a pathetical view of the development. It and was an enthusiastic devotee of Yiddish? presented the new historical ocurrences in Pa- The explanation is to be found in the vi- lestine as a renaissance and not as a continu- tal necessity which was felt by the pioneers ation of Jewish history, as a break and not as of the second Aliyah to achieve at all costs a continuity of the past. break from the past, from the large world of the The decision to create a political and a Russian revolutionary movements, from Rus- Hebrew cultural renaissance was laid down by sian culture, and Jewish Russian culture. -

Antisemitism 2.0”—The Spreading of Jew-Hatredonthe World Wide Web

MonikaSchwarz-Friesel “Antisemitism 2.0”—The Spreading of Jew-hatredonthe World Wide Web This article focuses on the rising problem of internet antisemitism and online ha- tred against Israel. Antisemitism 2.0isfound on all webplatforms, not justin right-wing social media but alsoonthe online commentary sections of quality media and on everydayweb pages. The internet shows Jew‐hatred in all its var- ious contemporary forms, from overt death threats to more subtle manifestations articulated as indirect speech acts. The spreading of antisemitic texts and pic- tures on all accessibleaswell as seemingly non-radical platforms, their rapid and multiple distribution on the World Wide Web, adiscourse domain less con- trolled than other media, is by now acommon phenomenon within the spaceof public online communication. As aresult,the increasingimportance of Web2.0 communication makes antisemitism generallymore acceptable in mainstream discourse and leadstoanormalization of anti-Jewishutterances. Empirical results from alongitudinalcorpus studyare presented and dis- cussed in this article. They show how centuries old anti-Jewish stereotypes are persistentlyreproducedacross different social strata. The data confirm that hate speech against Jews on online platforms follows the pattern of classical an- tisemitism. Although manyofthem are camouflaged as “criticism of Israel,” they are rooted in the ancient and medieval stereotypes and mental models of Jew hostility.Thus, the “Israelization of antisemitism,”¹ the most dominant manifes- tation of Judeophobia today, proves to be merelyanew garb for the age-old Jew hatred. However,the easy accessibility and the omnipresenceofantisemitism on the web 2.0enhancesand intensifies the spreadingofJew-hatred, and its prop- agation on social media leads to anormalization of antisemitic communication, thinking,and feeling. -

Varieties of Authenticity in Contemporary Jewish Identity

[133] Contempo- Varieties of Authenticity rary Jewish Identity in Contemporary Jewish • Identity Stuart Z. Charmé Stuart Z. Charmé uch discussion about religious pluralism among Orthodox and non-Orthodox Jews, about assimilation and Jewish conti- Mnuity, about Jewish life in Israel and in the Diaspora, and about a variety of other issues related to Jewish identity all invoke “authenticity” as the underlying ideal and as the ultimate legitimizer (or de-legitimizer) of various positions. In an address to the graduating class of Reconstructionist rabbis in 1983, Irving Howe encouraged the next generation of rabbis to “try for an atmosphere of authenticity, wherever you find yourselves.”1 An Orthodox rabbi in Philadelphia recently encouraged liberal Jews to share a Sabbath meal at an Orthodox home in order to see “how special an authentic Shabbas really is.”2 Israel, claimed Daniel Elazar, is “the only place in the world where an authentic Jewish culture can flourish (at least potentially). Even the more peripheral of American Jews are touched by the Jewish authenticity of Israel, while the more committed find the power of Israel in this respect almost irresistible.”3 And in response to such typical Zionist authenticity claims, one of Philip Roth’s literary alter egos proposes that Europe, not Israel, is “the most authentic Jewish homeland there has ever been, the birthplace of rabbinic Judaism, Hasidic Judaism, Jewish secularism, socialism, on and on.”4 Authenticity has become the key term for postmodern reconstruc- tions and “renewals” of