Petrology of the Host Rocks, Including Mineralisation and Adjacent Rock Sequences, from the Savage River Mine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17. Clay Mineralogy of Deep-Sea Sediments in the Northwestern Pacific, Dsdp, Leg 20

17. CLAY MINERALOGY OF DEEP-SEA SEDIMENTS IN THE NORTHWESTERN PACIFIC, DSDP, LEG 20 Hakuyu Okada and Katsutoshi Tomita, Department of Geology, Kagoshima University, Kagoshima 890, Japan INTRODUCTION intensity of montmorillonite can be obtained by sub- tracting the (001) reflection intensity of chlorite from the Clay mineral study of samples collected during Leg 20 of preheating or pretreating reflection intensity at 15 Å. the Deep Sea Drilling Project in the western north Pacific In a specimen with coexisting kaolinite and chlorite, was carried out mainly by means of X-ray diffraction their overlapping reflections make it difficult to determine analyses. Emphasis was placed on determining vertical quantitatively these mineral compositions. For such speci- changes in mineral composition of sediments at each site. mens Wada's method (Wada, 1961) and heat treatment Results of the semiquantitative and quantitative deter- were adopted. minations of mineral compositions of analyzed samples are The following shows examples of the determination of shown in Tables 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7. The mineral suites some intensity ratios of reflections of clay minerals. presented here show some unusual characters as discussed below. The influence of burial diagenesis is also evidenced Case 1 in the vertical distribution of some authigenic minerals. Montmorillonite (two layers of water molecules between These results may contribute to a better understanding silicate layers)—kaolinite mixture. of deep-sea sedimentation on the northwestern Pacific This is the situation in which samples contain both plate. montmorillonite and kaolinite. The first-order basal reflec- tions of these minerals do not overlap. When the (002) ANALYTICAL PROCEDURES reflection of montmorillonite, which appears at about 7 Å, Each sample was dried in air, and X-ray diffraction is absent or negligible, the intensity ratio is easily obtained. -

Download PDF About Minerals Sorted by Mineral Name

MINERALS SORTED BY NAME Here is an alphabetical list of minerals discussed on this site. More information on and photographs of these minerals in Kentucky is available in the book “Rocks and Minerals of Kentucky” (Anderson, 1994). APATITE Crystal system: hexagonal. Fracture: conchoidal. Color: red, brown, white. Hardness: 5.0. Luster: opaque or semitransparent. Specific gravity: 3.1. Apatite, also called cellophane, occurs in peridotites in eastern and western Kentucky. A microcrystalline variety of collophane found in northern Woodford County is dark reddish brown, porous, and occurs in phosphatic beds, lenses, and nodules in the Tanglewood Member of the Lexington Limestone. Some fossils in the Tanglewood Member are coated with phosphate. Beds are generally very thin, but occasionally several feet thick. The Woodford County phosphate beds were mined during the early 1900s near Wallace, Ky. BARITE Crystal system: orthorhombic. Cleavage: often in groups of platy or tabular crystals. Color: usually white, but may be light shades of blue, brown, yellow, or red. Hardness: 3.0 to 3.5. Streak: white. Luster: vitreous to pearly. Specific gravity: 4.5. Tenacity: brittle. Uses: in heavy muds in oil-well drilling, to increase brilliance in the glass-making industry, as filler for paper, cosmetics, textiles, linoleum, rubber goods, paints. Barite generally occurs in a white massive variety (often appearing earthy when weathered), although some clear to bluish, bladed barite crystals have been observed in several vein deposits in central Kentucky, and commonly occurs as a solid solution series with celestite where barium and strontium can substitute for each other. Various nodular zones have been observed in Silurian–Devonian rocks in east-central Kentucky. -

Mineralogy, Fluid Inclusion, and Stable Isotope Studies of the Hog Heaven Mining District, Flathead County, Montana

Montana Tech Library Digital Commons @ Montana Tech Graduate Theses & Non-Theses Student Scholarship Spring 2020 MINERALOGY, FLUID INCLUSION, AND STABLE ISOTOPE STUDIES OF THE HOG HEAVEN MINING DISTRICT, FLATHEAD COUNTY, MONTANA Ian Kallio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/grad_rsch Part of the Geological Engineering Commons MINERALOGY, FLUID INCLUSION, AND STABLE ISOTOPE STUDIES OF THE HOG HEAVEN MINING DISTRICT, FLATHEAD COUNTY, MONTANA by Ian Kallio A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Geoscience Geology Option Montana Tech 2020 ii Abstract The Hog Heaven mining district in northwestern Montana is unique in that it is a high- sulfidation epithermal system containing high Ag-Pb-Zn relative to Au-Cu, with a very high Ag to Au ratio (2,330:1). The deposits are hosted within the Cenozoic Hog Heaven volcanic field (HHVF), a 30 to 36 Ma suite that consists predominantly of rhyodacite flow-dome complexes and pyroclastic rocks. The HHVF is underlain by shallow-dipping siliclastic sediments of the Mesoproterozoic Belt Supergroup. These sediments are known to host important SEDEX (e.g., Sullivan) and red-bed copper (e.g., Spar Lake, Rock Creek, Montanore) deposits rich in Ag-Pb- Zn-Cu-Ba. The HHVF erupted through and deposited on the Belt strata during a period of Oligocene extension. Outcrops and drill core samples from Hog Heaven show alteration patterns characteristic of volcanic-hosted, high-sulfidation epithermal deposits. Vuggy quartz transitions laterally into quartz-alunite alteration where large sanidine phenocrysts (up to 4 cm) have been replaced by fine-grained, pink alunite, and/or argillic alteration that is marked by an abundance of white kaolinite-dickite clay. -

Geology and Hydrothermal Alteration of the Duobuza Goldrich Porphyry

doi: 10.1111/j.1751-3928.2011.00182.x Resource Geology Vol. 62, No. 1: 99–118 Thematic Articlerge_182 99..118 Geology and Hydrothermal Alteration of the Duobuza Gold-Rich Porphyry Copper District in the Bangongco Metallogenetic Belt, Northwestern Tibet Guangming Li,1 Jinxiang Li,1 Kezhang Qin,1 Ji Duo,2 Tianping Zhang,3 Bo Xiao1 and Junxing Zhao1 1Key Laboratory of Mineral Resources, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, CAS, Beijing, 2Tibet Bureau of Geology and Exploration, Lhasa, Tibet and 3No. 5 Geological Party, Tibet Bureau of Geology and Exploration, Golmu, China Abstract The Duobuza gold-rich porphyry copper district is located in the Bangongco metallogenetic belt in the Bangongco-Nujiang suture zone south of the Qiangtang terrane. Two main gold-rich porphyry copper deposits (Duobuza and Bolong) and an occurrence (135 Line) were discovered in the district. The porphyry-type mineralization is associated with three Early Cretaceous ore-bearing granodiorite porphyries at Duobuza, 135 Line and Bolong, and is hosted by volcanic and sedimentary rocks of the Middle Jurassic Yanshiping Formation and intermediate-acidic volcanic rocks of the Early Cretaceous Meiriqie Group. Simultaneous emplacement and isometric distribution of three ore-forming porphyries is explained as multi-centered mineralization generated from the same magma chamber. Intense hydrothermal alteration occurs in the porphyries and at the contact zone with wall rocks. Four main hypogene alteration zones are distinguished at Duobuza. Early-stage alteration is dominated by potassic alteration with extensive secondary biotite, K-feldspar and magnetite. The alteration zone includes dense magnetite and quartz-magnetite veinlets, in which Cu-Fe-bearing sulfides are present. -

Characterization of Elastic Tensors of Crustal Rocks with Respect to Seismic Anisotropy

Characterization of Elastic Tensors of Crustal Rocks with respect to Seismic Anisotropy Anissha Raju Department of Geological Sciences University of Colorado, Boulder Defense Date: April 5th, 2017 Thesis Advisor Assoc. Prof. Dr. Kevin Mahan, Department of Geological Sciences Thesis Committee Dr. Vera Schulte-Pelkum, Department of Geological Sciences Prof. Dr. Charles Stern, Department of Geological Sciences Dr. Daniel Jones, Honors Program ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Kevin Mahan and Dr. Vera Schulte-Pelkum for overseeing this thesis and initiating a seismic anisotropy reading seminar. Both have been very supportive towards my academic development and have provided endless guidance and support even prior to starting this thesis. Huge thanks to Dr. Charles Stern and Dr. Daniel Jones for serving on the committee and for their excellent academic instruction. Dr. Charles Stern has also been a big part of my academic career. I sincerely appreciate Dr. Sarah Brownlee for allowing me to use her MATLAB decomposition code and her contributions in finding trends in my plots. Thanks to Phil Orlandini for helping me out with generating MTEX plots. Special thanks to all the authors (listed in Appendix A) for providing me their sample elastic stiffness tensors and allowing it to be used in this study. I would also like to express my gratitude to Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (UROP) of University of Colorado Boulder for partly funding this study. Last but not least, I would like to thank my family and friends for being supportive -

Clay Minerals Soils to Engineering Technology to Cat Litter

Clay Minerals Soils to Engineering Technology to Cat Litter USC Mineralogy Geol 215a (Anderson) Clay Minerals Clay minerals likely are the most utilized minerals … not just as the soils that grow plants for foods and garment, but a great range of applications, including oil absorbants, iron casting, animal feeds, pottery, china, pharmaceuticals, drilling fluids, waste water treatment, food preparation, paint, and … yes, cat litter! Bentonite workings, WY Clay Minerals There are three main groups of clay minerals: Kaolinite - also includes dickite and nacrite; formed by the decomposition of orthoclase feldspar (e.g. in granite); kaolin is the principal constituent in china clay. Illite - also includes glauconite (a green clay sand) and are the commonest clay minerals; formed by the decomposition of some micas and feldspars; predominant in marine clays and shales. Smectites or montmorillonites - also includes bentonite and vermiculite; formed by the alteration of mafic igneous rocks rich in Ca and Mg; weak linkage by cations (e.g. Na+, Ca++) results in high swelling/shrinking potential Clay Minerals are Phyllosilicates All have layers of Si tetrahedra SEM view of clay and layers of Al, Fe, Mg octahedra, similar to gibbsite or brucite Clay Minerals The kaolinite clays are 1:1 phyllosilicates The montmorillonite and illite clays are 2:1 phyllosilicates 1:1 and 2:1 Clay Minerals Marine Clays Clays mostly form on land but are often transported to the oceans, covering vast regions. Kaolinite Al2Si2O5(OH)2 Kaolinite clays have long been used in the ceramic industry, especially in fine porcelains, because they can be easily molded, have a fine texture, and are white when fired. -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

06 11 09 Separation & Preparation of Biotite and Muscovite Samples For

06 11 09 Separation & Preparation of Biotite and Muscovite samples for 40Ar/39Ar analysis Karl Lang When dealing with detrital samples, sample contamination is a big problem. To avoid this at all costs be clean, this means handling samples one at a time and cleaning all equipment entirely after each sample handling. Only handle samples in a quite (i.e. not windy) environment, where there is little chance of spilling or blowing samples away. Handle samples over clean copier paper, and change the paper after each sample. Use compressed air (either canned or from a compressor) to clean all equipment in separation stages and methanol to keep equipment dirt and dust free in the preparation stages. This can be often be tedious work, I recommend finding a good book on tape or podcast to listen to. Estimate times to completion are stated. Detrital Samples Separation I. Sample drying (1-3 days) For detrital samples it is likely that samples will be wet. Simple let the samples dry in the open air, or under a mild lamp on paper plates. It may be necessary to occasionally stir up samples to get them to dry faster, if you do this, clean the stirrer after each sample. Split samples using a riffle splitter to obtain a quantity for the rest of the process, do this in the rock room. II. Sample Sieving (3-7 days) First locate a set of sieves that can be intensively cleaned. There are a set of appropriate sieves in 317 for this use, be careful using other's sieves as you will likely bend the meshes during cleaning. -

The Origin and Formation of Clay Minerals in Soils: Past, Present and Future Perspectives

Clay Minerals (1999) 34, 7–25 The origin and formation of clay minerals in soils: past, present and future perspectives M. J. WILSON Macaulay Land Use Research Institute, Craigiebuckler, Aberdeen AB15 8QH, UK (Received 23 September 1997; revised 15 January 1998) ABSTRACT: The origin and formation of soil clay minerals, namely micas, vermiculites, smectites, chlorites and interlayered minerals, interstratified minerals and kaolin minerals, are broadly reviewed in the context of research over the past half century. In particular, the pioneer overviews of Millot, Pedro and Duchaufour in France and of Jackson in the USA, are considered in the light of selected examples from the huge volume of work that has since taken place on this topic. It is concluded that these early overviews may still be regarded as being generally valid, although it may be that too much emphasis has been placed upon transformation mechanisms and not enough upon neoformation processes. This review also highlights some of the many problems pertaining to the origin and formation of soil clays that remain to be resolved. It has long been recognized that the minerals in the detail remained to be filled in, as well as a time that clay (<2 mm) fractions of soils play a crucial role in immediately pre-dated the widespread utilization in determining their major physical and chemical soil science of analytical techniques such as properties, and inevitably, questions concerning scanning electron microscopy, electron probe the origin and formation of these minerals have microanalysis, Mo¨ssbauer spectroscopy, electron assumed some prominence in soil science research. spin resonance spectroscopy and infrared spectro- This review considers some important aspects of scopy. -

Muscovite Solid Solutions in the System K20-Mgo-Feo-A1203-Sio2-H20: an Experimental Study at 2 Kbar Ph2o and Comparison with Natural Li-Free White Micas

MINERALOGICAL MAGAZINE, JUNE 1986, VOL. 50, PP. 257-66 Muscovite solid solutions in the system K20-MgO-FeO-A1203-SiO2-H20: an experimental study at 2 kbar PH2o and comparison with natural Li-free white micas GILLES MoNIER Laboratoire de P&rologie, Universit6 d'Or16ans, 45046 Orlrans Cedex, France AND JI~AN-LouIs ROBERT Centre de Recherche sur la Synthrse et Chimie des MinSraux, G.I.S.C.N.R.S.-B.R.G.M., 1A rue de la Frrollerie, 45071 Odrans Cedex 2, France ABSTRACT. This paper presents the results of an experi- K EY W OR O S : muscovite, phengite, solid solution, crystal- mental study of muscovite solid solutions in the system chemistry, experimental mineralogy, granites, hydro- K20-M~+O-A1203 SiO2-H20 (HF), with M2+= thermal alteration. Mg 2+ or Fe 2§ in the temperature range 300 700~ under 2 kbar P.~o, Muscovite solid solutions can be described, in this system, as the result of two substitutions. NATURAL lithium-free white micas are generally One is the phengitic substitution (x), which preserves the described as solid solutions between the muscovite pure dioctahedral character of the mica; the second is the end member K(A12R)(Si3AI)Olo(OH)2, where [] biotitic substitution (y), which leads to trioctahedral stands for an octahedral vacant site, and the micas and does not change the composition of the celadonite end member K(AIM z+ [3)Si4010(OH)2, tetrahedral layer Si3AI. The general formula of muscovite with M 2 + = Mg 2., Fe E+, thus, they are considered in this system is K(A12_~_2y/aM2+yOl_y/a)(Sia+~All_x) to belong to the so-called phengitic series. -

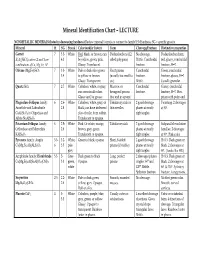

Mineral Identification Chart – LECTURE

Mineral Identification Chart – LECTURE NONMETALLIC MINERALS (listed in decreasing hardness) Review mineral formula to connect to family! H=Hardness; SG = specific gravity Mineral H SG Streak Color (and/or luster) Form Cleavage/Fracture Distinctive properties Garnet 7 3.5- White Red, black, or brown; can Dodecahedrons (12- No cleavage. Dodecahedron form, X3Y2(SiO4)3 where X and Y are 4.3 be yellow, green, pink. sided polygons) Brittle. Conchoidal red, glassy, conchoidal combinations of Ca, Mg, Fe, Al Glassy. Translucent. fracture. fracture, H=7. Olivine (Mg,Fe)2SiO4 7 3.3- White Pale or dark olive green Short prisms Conchoidal Green, conchoidal 3.4 to yellow or brown. (usually too small to fracture. fracture, glassy, H=7. Glassy. Transparent. see). Brittle. Usually granular. Quartz SiO2 7 2.7 White Colorless, white, or gray; Massive; or Conchoidal Glassy, conchoidal can occur in all colors. hexagonal prisms fracture. fracture, H=7. Hex. Glassy and/or greasy. that end in a point. prism with point end. Plagioclase Feldspar family: 6 2.6- White Colorless, white, gray, or Tabular crystals or 2 good cleavage Twinning. 2 cleavages Anorthite and Labradorite 2.8 black; can have iridescent thin needles planes at nearly at 90°. CaAl2Si2O8 to Oligoclase and play of color from within. right angles. Albite NaAlSi3O8 Translucent to opaque. Potassium Feldspar family: 6 2.5- White Pink. Or white, orange, Tabular crystals 2 good cleavage Subparallel exsolution Orthoclase and Microcline 2.6 brown, gray, green. planes at nearly lamellae. 2 cleavages KAlSi3O8 Translucent to opaque. right angles. at 90°. Pink color. Pyroxene family: Augite 5.5- 3.2- White, Green to black; opaque. -

Cr3+ in Phyllosilicates

Mineral Spectroscopy: A Tribute to Roger G. Bums © The Geochemical Society, Special Publication No.5, ]996 Editors: M. D. Dyar, C. McCammon and M. W. Schaefer 3 Cr + in phyllosilicates: Influence of the nature of coordinating ligands and their next cationic neighbors on the crystal field parameters I 2 2 A. N. PLATONOV , K. LANGER , M. ANDRUT .3, G. CALAS4 'Institute of Geochemistry, Mineralogy and Ore Formation, Academy of Science of Ukraine, 252680 Kiev, Ukraine 2Institute of Mineralogy and Crystallography, Technical University, D-10623 Berlin, Germany 3GeoForschungszentrum Potsdam, D-14473 Potsdam, Deutschland "Laboratoire de Mineralogie et de Cristallographie, Universite de Paris 6 et 7, F-7525l Paris, France 3 Abstract- The electronic absorption spectra of Cr + -bearing clinochlore (I, kammererite), amesite (II), muscovite (III, fuchsite), dickite (IV), and montmorillonite (V, volkonskite) analysed by electron microprobe were obtained on single crystals. Microscope-spectrometric techniques and polarized radiation in the spectral range 10000-38000 cm " (I, II, III) or (on fine grained material) diffuse reflectance spectrometry in the spectral range 8000-50000 cm-I (IV, V) were used. The ligand field theoretical evaluation of the spectra showed the following: (i) The fl.o = 10Dq = f(1/R5) relation, wherein fl.o is the octahedral crystal field parameter and R the mean cation ligand distance, is valid within each series of layer silicates containing octahedral Cr3+ either in a trioctahedral layer (I, II and phlogopite) or in a dioctahedral layer (III, IV, V). Between the two functions, fl.o.trioct = f(1lR~ioct) and fl.o.di=t = f(1/R~ioct), there exists an energy difference of about 2200 em -I.