C:\Documents and Settings\Pallotto\Desktop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resume: NKUGWA FRED

Resume: NKUGWA FRED Personal Information Application Title IT Professional First Name NKUGWA Middle Name N/A Last Name FRED Email Address [email protected] Cell 0700470333 Nationality Uganda Gender Male Category Computer/ IT Sub Category Computer Installations Services Job Type Full-Time Highest Education University Total Experience 1 Year Date of Birth 23-02-1996 Work Phone 0778728752 Home Phone 0700470333 Date you can start 01-01-1970 Driving License Yes License No. Searchable Yes I am Available Yes Address Address Address Kimaanya Masaka City Masaka State N/A Country Uganda Institutes Institute Uganda Martyrs University City Kampala State N/A Country Uganda Address Nkozi village- Kayabwe Kampala road Certificate Name Bachelor of Science in Information Technology Study Area Information Technology Employers Employer Employer Hirt IT Solutions Position Web developer Responsibilities Web design and programming ,computer repair, installation and trouble shooting ,database designing. Pay Upon Leaving N/A Supervisor Fr. Emmanuel From Date 18-06-2019 To Date 18-06-2021 Leave Reason Iam still working with the company City Masaka State N/A Country Uganda Phone +256783494405 Address Kilumba-Masaka Employer Employer Masaka Regional Referral Hospital Position Data Clerk Responsibilities • Database design and development • Hardware and Software Installation. • Data backup • Server room management • Network configuration. • Files and folder sharing. • Troubleshooting computers. • Website design and development Pay Upon Leaving N/A Supervisor Mr.Ssemakadde Mathew From Date 01-05-2019 To Date 01-08-2019 Leave Reason Industrial training period ended City Masaka State N/A Country Uganda Phone +256701717271 Address Masaka Uganda Skills Skills • Information security skills with a certificate from IBM skills academy USA. -

UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details)

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details) SUDAN NARENGEPAK KARENGA KATHILE KIDEPO NP !( NGACINO !( LOPULINGI KATHILE AGORO AGU FR PABAR AGORO !( !( KAMION !( Apoka TULIA PAMUJO !( KAWALAKOL RANGELAND ! KEI FR DIBOLYEC !( KERWA !( RUDI LOKWAKARAMOE !( POTIKA !( !( PAWACH METU LELAPWOT LAWIYE West PAWOR KALAPATA MIDIGO NYAPEA FR LOKORI KAABONG Moyo KAPALATA LODIKO ELENDEREA PAJAKIRI (! KAPEDO Dodoth !( PAMERI LAMWO FR LOTIM MOYO TC LICWAR KAPEDO (! WANDI EBWEA VUURA !( CHAKULYA KEI ! !( !( !( !( PARACELE !( KAMACHARIKOL INGILE Moyo AYUU POBURA NARIAMAOI !( !( LOKUNG Madi RANGELAND LEFORI ALALI OKUTI LOYORO AYIPE ORAA PAWAJA Opei MADI NAPORE MORUKORI GWERE MOYO PAMOYI PARAPONO ! MOROTO Nimule OPEI PALAJA !( ALURU ! !( LOKERUI PAMODO MIGO PAKALABULE KULUBA YUMBE PANGIRA LOKOLIA !( !( PANYANGA ELEGU PADWAT PALUGA !( !( KARENGA !( KOCHI LAMA KAL LOKIAL KAABONG TEUSO Laropi !( !( LIMIDIA POBEL LOPEDO DUFILE !( !( PALOGA LOMERIS/KABONG KOBOKO MASALOA LAROPI ! OLEBE MOCHA KATUM LOSONGOLO AWOBA !( !( !( DUFILE !( ORABA LIRI PALABEK KITENY SANGAR MONODU LUDARA OMBACHI LAROPI ELEGU OKOL !( (! !( !( !( KAL AKURUMOU KOMURIA MOYO LAROPI OMI Lamwo !( KULUBA Koboko PODO LIRI KAL PALORINYA DUFILE (! PADIBE Kaabong LOBONGIA !( LUDARA !( !( PANYANGA !( !( NYOKE ABAKADYAK BUNGU !( OROM KAABONG! TC !( GIMERE LAROPI PADWAT EAST !( KERILA BIAFRA !( LONGIRA PENA MINIKI Aringa!( ROMOGI PALORINYA JIHWA !( LAMWO KULUYE KATATWO !( PIRE BAMURE ORINJI (! BARINGA PALABEK WANGTIT OKOL KINGABA !( LEGU MINIKI -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized RP1030 v1 KAWANDA – MASAKA TRANSMISSION LINE Project Name: ELECTRICITY SECTOR DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Number: P119737 Report for: RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) PREPARATION, REVIEW AND AUTHORISATION Revision # Date Prepared by Reviewed by Approved for Issue by ISSUE REGISTER Distribution List Date Issued Number of Copies : April 2011 SMEC staff: Associates: Office Library (SMEC office location): SMEC Project File: SMEC COMPANY DETAILS Tel: Fax: Email: www.smec.com Review and Update Kawanda Masaka 220kV, 137km T Line 5116008 | June 13, 2011 Page | i We certify that this Resettlement Action Plan was conducted under our direct supervision and based on the Terms of Reference provided to us by Uganda Electricity Transmission Company Ltd. We hereby certify that the particulars given in this report are correct and true to the best of our knowledge. Table 1: RAP Review Team Resource Designation Signature Social-Economist/RAP M/s Elizabeth Aisu Specialist/Team leader Mr. Orena John Charles Registered Surveyor Mr. Ssali Nicholas Registered Valuer Mr. Yorokamu Nuwahambasa Sociologist Mr. Lyadda Nathan Social Worker M/s Julliet Musanyana Social Worker ACKNOWLEDGEMENT SMEC International wishes to express their gratitude to The Resettlement Action Plan (RAP) team, AFRICAN TECHNOLOGIES (U) Ltd and to all the persons who were consulted for their useful contributions that made the assessment successful. In this regard, Mr. Ian Kyeyune , LC5 Chairman Wakiso, M/s Joan Kironde, the then District Environment Officer Wakiso, M/s. Muniya Fiona, Sector Manager Mpigi, and to all the Local Council Leaders in all the affected Districts and the PAPs M/s Ziria Tibalwa Principal Planning Officer, Mr. -

Olweny Key Note.Pdf

Third RUFORUM Biennial Meeting 24 - 28 September 2012, Entebbe, Uganda Research Application Summary Providing opportunities to African youths and other disadvantaged groups: The Uganda Martyrs University approach/ strategy Olweny, C.L.M. MD, FRACP Uganda Martyrs University, P. O. Box 5498, Kampala, Uganda Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Youth is a period of building “self concept” often influenced by parents, peers, gender and culture. The United Nations (UN) youth agenda is guided by the World Programme of Action for Youths (WPAY) adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1995. WPAY has 15 priority areas. Africa is often regarded as the “youngest continent” because of the large number of young persons, and in Uganda, 49% of the population is under 15 years. Uganda Martyrs University (UMU) is a faith-based, private, not-for-profit institution founded in 1993 to address the perceived moral decay in business and professions. At UMU, ethics is a compulsory subject irrespective of one’s field of study. UMU obtained its civil charter in April 2005 and is one of only six out of 29 private universities in Uganda with this status. UMU places research and scholarship on top of its role agenda, followed by community engagement and finally teaching. UMU is located in a rural setting, and believes a university must not exist in isolation and that a university must be owned by the community where it is located. UMU’s focus areas include, inter-alia, HIV/AIDS, poverty alleviation, peace and justice and food security. UMU’s outreach project at Nnindye is to help the community lift itself out of poverty and all faculties are strongly encouraged to mainstream outreach in their curricula. -

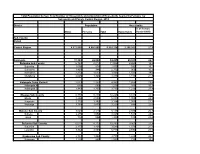

Population by Parish

Total Population by Sex, Total Number of Households and proportion of Households headed by Females by Subcounty and Parish, Central Region, 2014 District Population Households % of Female Males Females Total Households Headed HHS Sub-County Parish Central Region 4,672,658 4,856,580 9,529,238 2,298,942 27.5 Kalangala 31,349 22,944 54,293 20,041 22.7 Bujumba Sub County 6,743 4,813 11,556 4,453 19.3 Bujumba 1,096 874 1,970 592 19.1 Bunyama 1,428 944 2,372 962 16.2 Bwendero 2,214 1,627 3,841 1,586 19.0 Mulabana 2,005 1,368 3,373 1,313 21.9 Kalangala Town Council 2,623 2,357 4,980 1,604 29.4 Kalangala A 680 590 1,270 385 35.8 Kalangala B 1,943 1,767 3,710 1,219 27.4 Mugoye Sub County 6,777 5,447 12,224 3,811 23.9 Bbeta 3,246 2,585 5,831 1,909 24.9 Kagulube 1,772 1,392 3,164 1,003 23.3 Kayunga 1,759 1,470 3,229 899 22.6 Bubeke Sub County 3,023 2,110 5,133 2,036 26.7 Bubeke 2,275 1,554 3,829 1,518 28.0 Jaana 748 556 1,304 518 23.0 Bufumira Sub County 6,019 4,273 10,292 3,967 22.8 Bufumira 2,177 1,404 3,581 1,373 21.4 Lulamba 3,842 2,869 6,711 2,594 23.5 Kyamuswa Sub County 2,733 1,998 4,731 1,820 20.3 Buwanga 1,226 865 2,091 770 19.5 Buzingo 1,507 1,133 2,640 1,050 20.9 Maziga Sub County 3,431 1,946 5,377 2,350 20.8 Buggala 2,190 1,228 3,418 1,484 21.4 Butulume 1,241 718 1,959 866 19.9 Kampala District 712,762 794,318 1,507,080 414,406 30.3 Central Division 37,435 37,733 75,168 23,142 32.7 Bukesa 4,326 4,711 9,037 2,809 37.0 Civic Centre 224 151 375 161 14.9 Industrial Area 383 262 645 259 13.9 Kagugube 2,983 3,246 6,229 2,608 42.7 Kamwokya -

Planned Shutdowns Schedule-April 2021 System Improvement and Routine Maintenance

PLANNED SHUTDOWNS SCHEDULE-APRIL 2021 SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT AND ROUTINE MAINTENANCE REGION DAY DATE SUBSTATION FEEDER/PLANT PLANNED WORK DISTRICT AREAS & CUSTOMERS TO BE AFFECTED Kampala West Tuesday 06th April 2021 Mutundwe Kampala South 2 33kV feeder Replacement of rotten pole & jumper repairs Najjanankumbi None Line Clearance , Jumper repairs, Hv poles replumbing at Kalerwe, Bwaise Wood workshop, Nabweru, Kazo , Kibwa, Lugoba Tc, Kampala East Wednesday 07th April 2021 Kampala North Kawempe 11kV Bwaise and Conductor resurging at Happy hours T - off Wandegeya Happy hours Kawala Areas , Kawempe Hospital, Buddu Distillers, Mbale Bwaise Millers, Complant Bank of Baroda Kawempe and Kego Industries Mukono Industrial Area, Kigata, Mukono Industrial Area 1, Nsambwe Village, Nakabago Village, Nasuuti Tc, Kasangalabi Tc, Biyinzika Poultry Farm 2, Nalya Kisowera Village, Kituba Nabibuga Village,Mayangayanga Tc, Busenya Village, Kisowera Grinding Mill, Good Samaritan, Crane P/S, Kisowera T/C, KawalyaVision For Africa (Kiyunga), Krasna Industry (Kiyunga), Naro (Kabembe Forestry Research, Kabembe Forestry Kabembe T/C Research (Workshop), Kabembe Warid/Airtel Masts, Mpoma Satellite (Earth Station), Biyinzika Poultry Farm 1, Kimote Coffee Factory, Progressive Sec School, Nakifuma Gombolola Hqts, Kyeswa Benjamin Tx, Sai Beverages, Biyinzika Kabembe Tx, Marsenne Uganda Limited Tx, Hit Plastic Factory Tx, Tendo Coffee Factory Tx, Biyinzika Farm Nalya Tx 2, Fairland High School, Takajunge Atc Mast, Biyinzika Factory, Biyinzika Farm Nabiyagi, Biyinzika Farm -

Vote:540 Mpigi District Quarter4

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2019/20 Vote:540 Mpigi District Quarter4 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 4 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:540 Mpigi District for FY 2019/20. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Moses Kanyarutokye Date: 27/08/2020 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2019/20 Vote:540 Mpigi District Quarter4 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 1,415,067 1,073,885 76% Discretionary Government 2,706,488 2,684,408 99% Transfers Conditional Government Transfers 24,561,555 24,586,450 100% Other Government Transfers 2,903,505 912,520 31% External Financing 658,000 375,284 57% Total Revenues shares 32,244,614 29,632,547 92% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Administration 6,049,747 6,364,717 6,364,717 105% 105% 100% Finance 451,038 462,795 462,795 103% 103% 100% Statutory Bodies 1,141,787 883,262 883,262 77% 77% 100% Production and Marketing 2,501,609 1,089,458 1,089,458 44% 44% 100% Health 4,463,155 4,207,913 4,192,601 94% 94% 100% Education 14,596,068 -

Assessing Public Expenditure Governance in Uganda's Road Sector

ABOUT THE AUTHORS George Bogere is a Research Fellow at ACODE. He holds an MA Economics Degree from Makerere University. Before joining ACODE in January 2011, George was a Researcher at Makerere Institute of Social Research (MISR) - Makerere University for over five years. George is interested in Economic Assessing Public Expenditure Growth and Development, Decentralization, Governance and Service Delivery as well as Natural Resources Management particularly land. Governance in Uganda’s Road Sector Samuel Kayabwe holds an MA (Public Policy & Administration) from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA, 1993 and a BA (Economics & Rural Application of an Innovative Framework Economy) from Makerere University, Kampala Uganda. Over the past 25 years, Samuel has researched widely in the areas of pastoral land tenure and resource use issues; rural/agricultural development & poverty analysis; food security and livelihood systems; community natural resource management; governance and decentralization issues impacting on both rural and urban development; and basic education. Feza Kabasweka Greene is a Research Manager with Bayport Financial Services and a lecturer at Victoria University where she teaches Monetary Policy and Financial Systems, Portfolio Analysis and Quantitative Methods. Feza previously worked as a Research Assistant with DFID, Grameen Foundation and Economic Policy Research Center (EPRC). She holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Economics from the American University of Cairo and MSc in Africa and International Development from University of Edinburgh, Scotland. She has interest in economic development and policy analysis. Irene Achola is a Research Officer at ACODE. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Economics from Makerere University Kampala. She is currently pursuing a Masters degree in Public Administration and Management at Uganda Christian University. -

MASAKA BFP.Pdf

Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 533 Masaka District Structure of Budget Framework Paper Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2015/16 Page 1 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 533 Masaka District Foreword The contract form B is a vital document that combines the budget framework paper, Annual development plans and budgets into one document. It avails an opportunity to assess and evalaute perfomance on a quartely basis. Masaka District Council is therefore grateful to all the technical and political leadership for the zeal and ethusiasm expressed during the process of developing this document. I wish also to express my vote of thanks to our District Planner, Mr. Lukyamuzi Sunday Vincent for his effort that has enabled the production of this document. Further gratitude also goes to the line ministries and other partners for the technical guidance and resource support during this process. Kalungi Joseph- District Chairperson Page 2 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 533 Masaka District Executive Summary Revenue Performance and Plans 2014/15 2015/16 Approved Budget Receipts by End Proposed Budget September UShs 000's 1. Locally Raised Revenues 298,904 92,360 331,210 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 1,493,531 373,382 1,493,531 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 12,644,499 3,235,789 12,891,553 2c. Other Government Transfers 1,385,829 580,437 769,582 3. Local Development Grant 318,807 79,702 318,807 4. Donor Funding 1,453,482 550,585 1,387,420 Total Revenues 17,595,053 4,912,255 17,192,104 Revenue Performance in the first quarter of 2014/15 Considering a total receipt of UG.X.4,912,255,000, only UG.X.4,459,867,000 was spent during the first quarter of the FY 2014/15 and UG.X. -

Evaluating the Impact of Non-Governmental Organisations (Ngos) in Rural and Poverty Alleviation: Uganda Country Study

Jolifi de Gonini^ vvltit aimiiiiiM material by liiigirG.I»f!lclen Results of ODI research presented In preliminary form for dis@u^on and crHical comm«nt ODI \Yorking Papers available at February 1992 24: Industrialisation in Sub-Saharan Africa: Country case study: Cameroon Igor Karmiloff, 1988, £3.00, ISBN 0 85003 112 5 25: Industrialisation in Sub-Saharan Africa: Country case study: Zimbabwe Roger Riddell, 1988, £3.00, ISBN 0 85003 113 3 26: Industrialisation in Sub-Saharan Africa: Country case study: Zambia Igor Karmiloff, 1988, £3.00, ISBN 0 85003 114 1 27: European Community Trade Barriers to IVopical Agricultural Products Michael Davenport, 1988, £4.00, ISBN 0 85003 117 6 28: Trade and Hnandng Strategies for the New NICS: the Peru Case Study Jurgen Schuldt L., 1988, £3.00, ISBN 0 85003 118 4 29: The Control of Money Supply in Developing Countries: China, 1949-1988 Anita Santorum, 1989. £3.00, ISBN 0 85003 122 2 30: Monetary Policy Effectiveness in Cdte d'lvoire Christopher E. Lane, 1990, £3.00, ISBN 0 85003 125 7 31: Economic Development and the Adaptive Economy Tony Killick, 1990, £3.50, ISBN 0 85003 126 5 32: Principles of policy for the Adaptive Economy Tony KUlick, 1990, £3.50. ISBN 0 85003 127 3 33: Exchange Rates and Structural Adjustment Tony Killick, 1990, £3.50. ISBN 0 85003 128 1 34: Markets and Governments in Agricultural and Industrial Adjustment Tony Killick, 1990. £3.50. ISBN 0 85003 129 X 35: Financial Sector Policies in the Adaptive Economy Tony Killick, 1990, £3.50, ISBN 0 85003 131 1 37: Judging Success: Evaluating NGO Income-Generating Projects Roger Riddell, 1990, £3.50. -

Planned Shutdown June 2021

PLANNED SHUTDOWN FOR JUNE 2021 SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT AND ROUTINE MAINTENANCE REGION DAY DATE SUBSTATION FEEDER/PLANT PLANNED WORK DISTRICT AREAS & CUSTOMERS TO BE AFFECTED North Eastern Saturday 05th June 2021 Tororo Main 80MVA 132/33kV Completion of snags on the 80MVA 132/33kV Zest WEG TX3 Tororo Tororo Cement Industries, Hima Cement, Uganda Cement, Tororo Town, Zest WEG TX 3 Nagongera, Mbale, Busia, Bugiri, Busitema, Jinja Rd, Parts Of Kumi, Lumino, Namayengo, Tirinyi Rd, Mbale-tororo Rd, Bubulo, Iki Iki, Nagongera, And Surroundings Kampala East Saturday 05th June 2021 Njeru Ring North 11kv Feeder Power Connection To Nalufenya Atc Mast Jinja Kimaka, Part Of Jinja Town, Nile Restort, Jinja Hospital, Sunset Hotel Kampala West Sunday 06th June 2021 Motomart 11kV Switchgear Rotuine Maintenance of Switchgear Metro Press house, Ebb rd traffic lights, Radio one, Namaganda plaza, Holday Express hotel, BOU, Posta ug, Amber house, Collin house, Stan chart and former green land towers, Metro offices, Christ the King, Communication house, Min. foreign affairs, Auditor general, KCCA, Statistics house, Speke hotel Workers house span house NIC building and DTB, Cham Towers and Nkrumah rd, Uganda House, Jinja rd and Nkrumah rd, Nasser road, Nkurumah road, Market street, Nakasero mkt and Luwum street, South street, UCB and Uganda house, Kampala West Sunday 06th June 2021 Motomart Auxillary Transformer Maintenance of Auxillary Transformer Metro Press house, Ebb rd traffic lights, Radio one, Namaganda plaza, Holday Express hotel, BOU, Posta ug, Amber house, -

Office of the Auditor General

OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF MPIGI DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2017 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ........................................................................................................ iii Key Audit Matters ............................................................................................................. 5 Utilization of Medicines and Medical Supplies...................................................... 5 Unaccounted for Medicines and Health Supplies ................................................. 6 Expired drugs ............................................................................................................. 6 Failure to Implement Budget as approved by Parliament .................................. 6 Low Recovery of Youth Livelihood Program funds .............................................. 7 Under Staffing ............................................................................................................ 8 Failure to meet the minimum standards in Primary Schools .............................. 8 Management’s Responsibility for the Financial Statements ....................................... 9 Auditor’s Responsibilities for the Audit of the Financial Statements ........................ 9 Appendices....................................................................................................................... 12 Appendix