West Nile Virus Reporting and Investigation Guideline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson of the Month (2)

CMJ0906-Pande_LoM.qxd 11/17/09 9:58 AM Page 626 7 Nelson RL, Persky V, Davis F, Becker E. Risk of disease in siblings Address for correspondence: Dr SD Pande, Changi of patients with hereditary haemochromatosis. Digestion General Hospital, 2 Simei Street 3, Singapore 529889. 2001;64:120–4. Email: [email protected] 8 Reyes M, Dunet DO, Isenberg KB, Trisoloni M, Wagener DK. Family based detection for hereditary haemochromatosis. J Genet Couns 2008;17:92–100. Clinical Medicine 2009, Vol 9, No 6: 626–7 lesson of the month (2) negative. He was treated empirically with intravenous acyclovir and ceftriaxone for three days before all these culture results were Considering syphilis in aseptic meningitis available. He subsequently made a very good recovery. As part of a screen for other causes of aseptic meningitis, syphilis serology was Clinicians need to consider syphilis in the differential requested which was positive for immunoglobulin M (IgM) anti- diagnosis of macular or papular rashes with body and venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) was posi- neurological conditions, particularly aseptic meningitis, tive with a titre of 1:64. This was confirmed with a repeat sample. as early diagnosis and treatment lead to a better The patient therefore continued treatment with ceftriaxone for prognosis. two weeks. As part of contact tracing his wife, who was asympto- matic, was screened for syphilis and was found to have positive serology. She was treated with a standard regime of benzathine penicillin. On follow-up, both showed good responses serologi- cally and both patients tested negative for HIV. Lesson In March 2007 a 45-year-old heterosexual male presented to the Discussion medical assessment unit with a three-week history of headaches, occasional vomiting and more recent confusion. -

West Nile Virus Aseptic Meningitis and Stuttering in Woman

LETTERS Author affi liation: University of the Punjab, Address for correspondence: Muhammad having received multiple mosquito Lahore, Pakistan Idrees, Division of Molecular Virology and bites during the preceding weeks. Molecular Diagnostics, National Centre of At admission, she had a DOI: 10.3201/eid1708.100950 Excellence in Molecular Biology, University temperature of 101.3°F, pulse rate of Punjab, 87 West Canal Bank Rd, Thokar of 92 beats/min, blood pressure of References Niaz Baig, Lahore 53700, Pakistan; email: 130/80 mm Hg, and respiratory rate of 1. Idrees M, Lal A, Naseem M, Khalid M. [email protected] 16 breaths/min. She appeared mildly High prevalence of hepatitis C virus infec- ill but was alert and oriented with no tion in the largest province of Pakistan. nuchal rigidity, photophobia, rash, or J Dig Dis. 2008;9:95–103. doi:10.1111/ j.1751-2980.2008.00329.x limb weakness. Results of a physical 2. Martell M, Esteban JI, Quer J, Genesca examination were unremarkable, and J, Weiner A, Gomez J. Hepatitis C virus results of a neurologic examination circulates as a population of different but were notable only for stuttering. closely related genomes: quasispecies na- ture of HCV genome distribution. J Virol. Laboratory test results included a West Nile Virus 3 1992;66:3225–9. leukocyte count of 12,300 cells/mm 3. Jarvis LM, Ludlam CA, Simmonds P. Hep- Aseptic Meningitis (63% neutrophils, 29% lymphocytes, atitis C virus genotypes in multi-transfused 7% monocytes, 1% basophils) and individuals. Haemophilia. 1995;1(Sup- and Stuttering in pl):3–7. -

The Challenge of Drug-Induced Aseptic Meningitis

REVIEW ARTICLE The Challenge of Drug-Induced Aseptic Meningitis German Moris, MD; Juan Carlos Garcia-Monco, MD everal drugs can induce the development of aseptic meningitis. Drug-induced aseptic men- ingitis (DIAM) can mimic an infectious process as well as meningitides that are secondary to systemic disorders for which these drugs are used. Thus, DIAM constitutes a diagnostic and patient management challenge. Cases of DIAM were reviewed through a MEDLINE Sliterature search (up to June 1998) to identify possible clinical and laboratory characteristics that would be helpful in distinguishing DIAM from other forms of meningitis or in identifying a specific drug as the culprit of DIAM. Our review showed that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antibiotics, intravenous immunoglobulins, and OKT3 antibodies (monoclonal antibodies against the T3 receptor) are the most frequent cause of DIAM. Resolution occurs several days after drug discon- tinuation and the clinical and cerebrospinal fluid profile (neutrophilic pleocytosis) do not allow DIAM to be distinguished from infectious meningitis. Nor are there any specific characteristics associated with a specific drug. Systemic lupus erythematosus seems to predispose to NSAID-related meningi- tis. We conclude that a thorough history on prior drug intake must be conducted in every case of meningitis, with special focus on those aforementioned drugs. If there is a suspicion of DIAM, a third- generation cephalosporin seems a reasonable treatment option until cerebrospinal fluid cultures are available. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1185-1194 Several drugs can induce meningitis, re- been associated with drug-induced aseptic sulting in a diagnostic and therapeutic meningitis (DIAM) (Table 1): nonsteroi- challenge. -

Wnv-Case-Definition.Pdf

Draft Case Definition for West Nile Fever Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service West Nile Fever Veterinary Services October 2018 Case Definition (Notifiable) 1. Clinical Signs 1.1 Clinical Signs: West Nile Fever (WNF) is a zoonotic mosquito-borne viral disease caused by the West Nile virus (WNV), a Flavivirus of the family Flaviviridae. Many vertebrate species are susceptible to natural WNV infection; however, fatal neurological outbreaks have only been documented in equids, humans, geese, wild birds (particularly corvids), squirrels, farmed alligators, and dogs. Birds serve as the natural host reservoir of WNV. The incubation period is estimated to be three to 15 days in horses Ten to 39 percent of unvaccinated horses infected with WNV will develop clinical signs. Most clinically affected horses exhibit neurological signs such as ataxia (including stumbling, staggering, wobbly gait, or incoordination) or at least two of the following: circling, hind limb weakness, recumbency or inability to stand (or both), multiple limb paralysis, muscle fasciculation, proprioceptive deficits, altered mental status, blindness, lip droop/paralysis, teeth grinding. Behavioral changes including somnolence, listlessness, apprehension, or periods of hyperexcitability may occur. Other common clinical signs include colic, lameness, anorexia, and fever. 2. Laboratory criteria: 2.1 Agent isolation and identification: The virus can be identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and virus isolation (VI). Preferred tissues from equids are brain or spinal cord. 2.2 Serology: Antibody titers can be identified in paired serum samples by IgM and IgG capture enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT), and virus neutralization (VN). Only a single serum sample is required for IgM capture ELISA, and this is the preferred serologic test in live animals. -

Aseptic Meningitis Face Sheet

Aseptic Meningitis Face Sheet 1. What is aseptic meningitis (AM)? - AM refers to a viral infection of the meninges (a system of membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord). It is a fairly common disease, however, almost all cases occur as an isolated event, and outbreaks are rare. 2. Who gets AM? - Anyone can get AM but it occurs most often in children. 3. What viruses cause this form of meningitis? - Approximately half of the cases of AM in the United States are caused by common intestinal viruses (enteroviruses). Occasionally, children develop AM associated with either mumps or herpes virus infection. Mosquito-borne viruses: e.g. WNV also account for a few cases each year in Pennsylvania. In most cases, the specific virus is never identified. 4. How are viruses that cause AM spread? - In the absence of a specific laboratory diagnosis of the causative AM virus, it is difficult to implement targeted prevention measures as some are spread person-to-person while others are spread by insects. 5. What are the symptoms? - They include fever, headache, stiff neck and fatigue. Rash, sore throat and intestinal symptoms may also occur. 6. How soon do symptoms appear? - Generally appear within one week of exposure. 7. How is AM diagnosed? – The only way to diagnose AM is to collect a sample of spinal fluid through a lumbar puncture (also known as a spinal tap). 8. Is a person with AM contagious? – While some of the enteroviruses that may cause AM are potentially contagious person to person, others, such as mosquito- borne viruses, cannot be spread person to person. -

Rift Valley Fever for Host Innate Immunity in Resistance to a New

A New Mouse Model Reveals a Critical Role for Host Innate Immunity in Resistance to Rift Valley Fever This information is current as Tânia Zaverucha do Valle, Agnès Billecocq, Laurent of September 25, 2021. Guillemot, Rudi Alberts, Céline Gommet, Robert Geffers, Kátia Calabrese, Klaus Schughart, Michèle Bouloy, Xavier Montagutelli and Jean-Jacques Panthier J Immunol 2010; 185:6146-6156; Prepublished online 11 October 2010; Downloaded from doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000949 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/185/10/6146 Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2010/10/12/jimmunol.100094 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Material 9.DC1 References This article cites 46 articles, 17 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/185/10/6146.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. by guest on September 25, 2021 • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2010 by The American -

Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy and the Spectrum of JC Virus-Related Disease

REVIEWS Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and the spectrum of JC virus- related disease Irene Cortese 1 ✉ , Daniel S. Reich 2 and Avindra Nath3 Abstract | Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a devastating CNS infection caused by JC virus (JCV), a polyomavirus that commonly establishes persistent, asymptomatic infection in the general population. Emerging evidence that PML can be ameliorated with novel immunotherapeutic approaches calls for reassessment of PML pathophysiology and clinical course. PML results from JCV reactivation in the setting of impaired cellular immunity, and no antiviral therapies are available, so survival depends on reversal of the underlying immunosuppression. Antiretroviral therapies greatly reduce the risk of HIV-related PML, but many modern treatments for cancers, organ transplantation and chronic inflammatory disease cause immunosuppression that can be difficult to reverse. These treatments — most notably natalizumab for multiple sclerosis — have led to a surge of iatrogenic PML. The spectrum of presentations of JCV- related disease has evolved over time and may challenge current diagnostic criteria. Immunotherapeutic interventions, such as use of checkpoint inhibitors and adoptive T cell transfer, have shown promise but caution is needed in the management of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, an exuberant immune response that can contribute to morbidity and death. Many people who survive PML are left with neurological sequelae and some with persistent, low-level viral replication in the CNS. As the number of people who survive PML increases, this lack of viral clearance could create challenges in the subsequent management of some underlying diseases. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is for multiple sclerosis. Taken together, HIV, lymphopro- a rare, debilitating and often fatal disease of the CNS liferative disease and multiple sclerosis account for the caused by JC virus (JCV). -

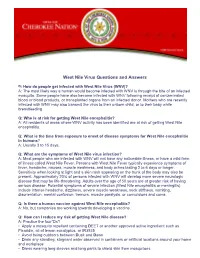

West Nile Virus Questions and Answers

West Nile Virus Questions and Answers Q: How do people get infected with West Nile Virus (WNV)? A: The most likely way a human would become infected with WNV is through the bite of an infected mosquito. Some people have also become infected with WNV following receipt of contaminated blood or blood products, or transplanted organs from an infected donor. Mothers who are recently infected with WNV may also transmit the virus to their unborn child, or to their baby while breastfeeding. Q: Who is at risk for getting West Nile encephalitis? A: All residents of areas where WNV activity has been identified are at risk of getting West Nile encephalitis. Q: What is the time from exposure to onset of disease symptoms for West Nile encephalitis in humans? A: Usually 3 to 15 days. Q: What are the symptoms of West Nile virus infection? A: Most people who are infected with WNV will not have any noticeable illness, or have a mild form of illness called West Nile Fever. Persons with West Nile Fever typically experience symptoms of fever, headache, nausea, muscle weakness, and body aches lasting 2 to 6 days or longer. Sensitivity when looking at light and a skin rash appearing on the trunk of the body may also be present. Approximately 20% of persons infected with WNV will develop more severe neurologic disease that may be life-threatening. Adults over the age of 50 years are at greater risk of having serious disease. Potential symptoms of severe infection (West Nile encephalitis or meningitis) include intense headache, dizziness, severe muscle weakness, neck stiffness, vomiting, disorientation, mental confusion, tremors, muscle paralysis, or convulsions and coma. -

Download Full Text

CASE SERIES Varicella Zoster Meningitis in Immunocompetent Hosts: A Case Series and Review of the Literature Sanjay Bhandari, MD; Carrie Alme, MD; Alfredo Siller, Jr, MD; Pinky Jha, MD ABSTRACT describes 2 immunocompetent men and 1 Meningitis caused by varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection is uncommon in immunocompetent immunocompetent woman who had VZV patients. We report 3 cases of VZV meningitis with rash in immunocompetent adults from a sin- meningitis associated with rash. gle academic institution over a 1-year period. The low prevalence of VZV meningitis in this popu- lation is attributed to lack of early recognition or underreporting. We highlight the importance of CASE 1 considering VZV as a possible cause of meningitis even in previously healthy young individuals. A 22-year-old man with a past medical history significant for primary varicella as an infant and mononucleosis in 8th grade presented with headache, fever, photo- INTRODUCTION phobia, and painful vesicular rash over the scalp. Vital signs were Meningitis is characterized by inflammation of the layers of tissue within normal limits except for a low-grade fever of 100.7º F. encasing the brain and spinal cord and is primarily caused by viral Physical exam was significant for generalized anterior cervical infections. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) is one of the common lymphadenopathy and a 1.5 cm x 3 cm left-sided retro-auricular causes of viral meningitis and is rare in otherwise healthy individ- lymph node. Nuchal rigidity with pain was noted; Brudzinski’s uals.1 Following a primary VZV infection, which is often asymp- and Kernig’s signs were negative. -

Aseptic Meningitis Epidemic During a West Nile Virus Avian Epizootic Kathleen G

RESEARCH Aseptic Meningitis Epidemic during a West Nile Virus Avian Epizootic Kathleen G. Julian,* James A. Mullins,† Annette Olin,‡ Heather Peters,§ W. Allan Nix,† M. Steven Oberste,† Judith C. Lovchik,¶ Amy Bergmann,§ Ross J. Brechner,§ Robert A. Myers,§ Anthony A. Marfin,* and Grant L. Campbell* While enteroviruses have been the most commonly ance of emerging infectious agents such as West Nile virus identified cause of aseptic meningitis in the United States, (WNV), warrants periodic reevaluation. the role of the emerging, neurotropic West Nile virus (WNV) WNV infection is usually asymptomatic but may cause is not clear. In summer 2001, an aseptic meningitis epidem- a wide range of syndromes including nonspecific febrile ic occurring in an area of a WNV epizootic in Baltimore, illness, meningitis, and encephalitis. In recent WNV epi- Maryland, was investigated to determine the relative contri- butions of WNV and enteroviruses. A total of 113 aseptic demics in which neurologic manifestations were promi- meningitis cases with onsets from June 1 to September 30, nent (Romania, 1996 [5]; United States, 1999–2000 [6,7]; 2001, were identified at six hospitals. WNV immunoglobu- and Israel, 2000 [8]), meningitis was the primary manifes- lin M tests were negative for 69 patients with available tation in 16% to 40% of hospitalized patients with WNV specimens; however, 43 (61%) of 70 patients tested disease. However, because WNV meningitis has nonspe- enterovirus-positive by viral culture or polymerase chain cific clinical manifestations and requires laboratory testing reaction. Most (76%) of the serotyped enteroviruses were for a definitive diagnosis, case ascertainment and testing echoviruses 13 and 18. -

West Nile Virus

Oklahoma State Department of Health Acute Disease Service Public Health Fact Sheet West Nile Virus What is West Nile virus? West Nile virus is one of a group of viruses called arboviruses that are spread by mosquitoes and may cause illness in birds, animals, and humans. West Nile virus was not known to be present in the United States until the summer of 1999. Previously, West Nile virus was only found in Africa, western Asia, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe. Where is West Nile virus in the United States? West Nile virus was first identified as a disease threat in the United States during the summer of 1999 and was limited to the northeastern states through 2000. However, the virus rapidly expanded its geographic range. By the end of 2004, West Nile virus had spread from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast with viral activity confirmed in all 48 contiguous states. How is it spread? West Nile virus is primarily spread through the bite of an infected mosquito. Mosquitoes pick up the virus when they feed on infected birds. The virus must then circulate in the mosquito for a few days before they are capable of passing the infection to animals or humans while biting. West Nile virus is not spread person to person through casual contact such as touching or kissing. Rarely, West Nile virus has also been spread through blood transfusions, although blood banks do screen blood supply for the infection. How long does it take to get sick after a bite from an infected mosquito? It takes about three to 15 days for both human and equine (horse, mule, or donkey) illness to occur after a bite from infected mosquito. -

Viral Meningitis Fact Sheet

Viral ("Aseptic") Meningitis What is meningitis? Meningitis is an illness in which there is inflammation of the tissues that cover the brain and spinal cord. Viral or "aseptic" meningitis, which is the most common type, is caused by an infection with one of several types of viruses. Meningitis can also be caused by infections with several types of bacteria or fungi. In the United States, there are between 25,000 and 50,000 hospitalizations due to viral meningitis each year. What are the symptoms of meningitis? The more common symptoms of meningitis are fever, severe headache, stiff neck, bright lights hurting the eyes, drowsiness or confusion, and nausea and vomiting. In babies, the symptoms are more difficult to identify. They may include fever, fretfulness or irritability, difficulty in awakening the baby, or the baby refuses to eat. The symptoms of meningitis may not be the same for every person. Is viral meningitis a serious disease? Viral ("aseptic") meningitis is serious but rarely fatal in persons with normal immune systems. Usually, the symptoms last from 7 to 10 days and the patient recovers completely. Bacterial meningitis, on the other hand, can be very serious and result in disability or death if not treated promptly. Often, the symptoms of viral meningitis and bacterial meningitis are the same. For this reason, if you think you or your child has meningitis, see your doctor as soon as possible. What causes viral meningitis? Many different viruses can cause meningitis. About 90% of cases of viral meningitis are caused by members of a group of viruses known as enteroviruses, such as coxsackieviruses and echoviruses.