Kent Academic Repository Full Text Document (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dato' Lee Chong Wei Parkson's Brand Ambassador

VOL. 28 NO. 5 SEPTEMBER / OCTOBER 2016 FOR INTERNAL CIRCULATION ONLY www.lion.com.my PP19070/08/2016(034572) DATO’ LEE CHONG WEI PARKSON’S BRAND AMBASSADOR ▼ Parkson Fashion Spotlight Relaunch of Centro Ambarrukmo Plaza, Indonesia ▼ Opening of Hogan Bakery in Shanghai ▼ 2017 Malaysian Budget Highlights ▼ Grand Launch of Shoopen at Farenheit88 RETAIL & TRADING DIVISION DATO’ LEE CHONG WEI - PARKSON’S BRAND AMBASSADOR ▼ Tan Sri William Cheng presenting a jersey signed by Dato’ Lee Chong Wei to a lucky guest. ▼ ▼ From left: Mr BE Law, Tan Sri William Cheng, Dato’ Lee Chong Wei and Mr Shaun Chong Tan Sri William Cheng menyampaikan sehelai at the press conference. jersey bertandatangan Dato’ Lee Chong Wei ▼ Dari kiri: Encik BE Law, Tan Sri William Cheng, Dato’ Lee Chong Wei dan Encik Shaun Chong semasa kepada seorang tetamu yang bertuah. sidang media. ▼ Cake-cutting ceremony by Tan Sri William Cheng and Dato’ Lee ▼ Dato’ Lee Chong Wei accompanied by Tan Sri William Cheng, Chong Wei in conjunction with Parkson’s 29th Anniversary celebration. Mr BE Law and Mr Shaun Chong on a tour of Parkson Pavilion. ▼ Upacara memotong kek oleh Tan Sri William Cheng dan Dato’ Lee Chong ▼ Dato’ Lee Chong Wei diiringi Tan Sri William Cheng, Encik BE Law dan Wei sempena sambutan ulangtahun ke-29 Parkson. Encik Shaun Chong melawat Parkson Pavilion. CORPORATE UPDATE Lion Group Director and Lion-Parkson Foundation Trustee, Datuk CS Tang was conferred the Darjah Kebesaran Panglima Jasa Negara (PJN) which carries the title of ‘Datuk’ by DYMM Seri Paduka Baginda Yang Di-Pertuan Agong, Tuanku Abdul Halim Mu’adzam Shah in conjunction with His Majesty’s Official Birthday recently this year. -

O U R O D Y S S

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 OUR ODYSSEY MediaPrima AT A GLANCE CONTENTS WHO WE ARE HOW WE ARE GOVERNED 4 Corporate Profile 91 Corporate Governance Overview Statement 6 Our Milestones 109 Additional Compliance Information 9 Corporate Structure 110 Statement on Risk Management and Internal Control 10 Organisation Structure 121 Audit Committee Report 12 Snapshots of 2017 127 Risk Management Committee Report 16 Awards and Recognition 2017 OUR NUMBERS OUR PERFORMANCE REVIEW 130 Financial Statements 20 Group Chairman’s Statement 24 Group Managing Director’s Statement-MD&A ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 30 Review of Operations 213 Analysis of Shareholdings 54 Segmental Analysis 216 Top 10 Properties Held by the Group 55 Statement of Value Added & Distribution of Value Added 217 Corporate Information 56 Viewership, Listenership & Readership Data 57 Share Price Chart 58 Group Financial Review AGM INFORMATION 219 Notice of Annual General Meeting 221 Statement Accompanying Notice of Annual General OUR COMMITMENT TO SUSTAINABILITY Meeting 60 Sustainability Report 222 Financial Calendar 75 Investor Relations • Proxy Form OUR LEADERSHIP • Group Directory 76 Our Board of Directors 78 Directors' Profile 86 Senior Management Team OUR ODYSSEY As digital disruption takes full form, we at Media Prima aim to embrace the many opportunities that come with it. In 2017, Media Prima embarked on our Odyssey Transformation Plan – a strategic initiative to reinvent the Group to become the leading digital-first content and commerce entity. In doing this, we will continue to enrich lives by informing, entertaining and engaging across all media, just as how we have been doing for decades. The only difference is that we are doing them all with a strong focus on digital platform. -

Gossip Girl Season / Year 3

For Immediate release Stop! Look, taste, sense and marvel at the beauty of MALAYSIA in It’s time to foster an appreciation of the familiar scent of home exclusively on 8TV TX Date : 16 October 2011 – 8 January 2012 Day/Time : Every Sunday, 7.30pm Duration : 30mins No. of Epi : 13 episodes Language : Mandarin Hosts : Henley Hii & Natelie (Xiao Yu) KUALA LUMPUR, 6th October 2011 - Beautiful beaches, colourful culture, amazing sceneries and mouth watering delicacies are just some of the spectacular experiences you get as the Ministry of Tourism, Tourism Malaysia and 8TV take you on an adventure in – a charismatic reality show that takes you on an expedition through the wonders of Malaysia. Beginning 16th October 2011, at 7.30pm exclusively on 8TV, will take you on an unforgettable journey as you explore the local sights and sounds together with host Henley Hii and Natalie. Venture deep into the heart of Malaysia and not only see but experience the daily lives of its people, the captivating sceneries as well as the history and culture that lies behind this tropical wonderland we call - MALAYSIA. not only takes you on a new escapade with newer findings, but it also introduces you to an entirely new way for you to pack up and travel. Its aim is to showcase the country‟s top locations and most captivating places to visit without splurging too much on the moolah. From Raub, Frasers Hill, Kluang, Sungai Pandan, Putrajaya, Rasah, Melaka, Kuantan, Penang, Langkawi, Kuala Krai, Sandakan and many other interesting stops, catch Henley and Natalie as they visit the Tunku Abdul Rahman Park Island, Turtle island Park, Sepilok Orang Utan Rehab Centre, War Museum, Menara Condong, Portugese settlement, food hunting and countless other fun-filled escapades. -

Koharu Kusumi ⼩ 春 the First Essay of Nonfiction Koharu Kusumi Has Wrien! a Nature-Raised Village Girl Becomes an Idol at Age and at Age Now Takes a New Path

A Career Change at 17 転 歳 職 の 久 住 Koharu Kusumi ⼩ 春 The first essay of nonfiction Koharu Kusumi has wrien! A nature-raised village girl becomes an idol at age and at age now takes a new path. The mental state of Koharu Kusumi arriving at a career change at age , pursued since early life. Her road to health, her road to agriculture, her Morning Musume。 period experiences—she talks about everything here now!! “The complete audition conditions” “Kirari Tsukishima-chan,thank you” “You could pay for bamboo shoots!” “Modeling aspirations” An intense open-air classroom “I’m quiing Morning Musume 。!” “Like I’m gonna die in a place like this!” “Could I really turn being “An interest in agriculture” an otaku into a career?” “It’s an important thing for the sake of being healthy” “Koharu talks about hygiene” 17 A 歳 Career の Change 転 at 職 久 Koharu 住 小 Kusumi 春 an unofficial translation with notes by KirarinISnow photographs koharu kusumi d i e t n o t e \ · [ · \ · [ · \ · [ · \ · [ · \ · [ · \ · [ · \ · [ · \ · [ · \ · [ · \ · [ A Career Change at Foreword Koharu’s Hometown :Life in Washima Village: ⟦The birth of Koharu Kusumi (ages –)⟧ .................... Stories from age that I have no recollection of ............ This is what a village nursery school is () ............. Lile Koharu’s reality! :A day in the life of Koharu: ........ Koharu’s nature becomes clear :Age : ................ ⟦Four seasons in a retro village⟧ ......................... Winters with tremendous snowfall .................... For the Kusumis, the year starts with “New Year’s Eve”—“The New Year’s performances are on December , aren’t they?” . -

Lived Experiences of “Beautiful” Women: a Postmodern Feminist Exploration of Beauty Discourse and Identity

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Michelle Marie for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Design and Human Environment presented on June 9, 2016. Title: Lived Experiences of “Beautiful” Women: A Postmodern Feminist Exploration of Beauty Discourse and Identity Abstract Approved: Brigitte G. Cluver While a great deal is known about the benefits of being culturally identified as attractive, very little is known about the lived experiences of beautiful women. In this study, 21 adult women who are currently employed as models or represented by modeling agencies participated in open-ended interviews, and their responses were analyzed using a Foucauldian and postmodern feminist theoretical framework. Findings generally support and complicate the conclusions of extant research: Beautiful women are shown to have a complex definition of beauty, an awareness of being understood by society as beautiful, positive and negative experiences that are associated with being beautiful, feelings of confidence, and opportunities for creativity within modeling work. Interpretation of findings via a Foucauldian and postmodern feminist framework reveals ways in which power, knowledge, and subjectivation combine in participants’ lived experiences and problematizes beauty discourse and the identities of “beautiful” women subjects. Power deploys discourses of “beauty” and “modeling” and employs multiple strategies that conceal and simultaneously reinforce their existence. Knowledge is present in participants’ lives in several ways, and is applied by participants in service of power and to construct their identities as “beautiful” subjects. Subjectivation, or participants’ development of a relationship to themselves, occurs physically via beauty practices and mentally via the choices they make in how they view themselves and represent themselves to others. -

CIE Fashion Magazine Feat: Angelina Cruz

CIE Fashion Magazine ciefashionmagazine.com Editor in chief Damian Sanders Senior Contributor Dira Ve Photographer Juan Carlos Guevara Photographer TEEE Briscoe Senior Contributor/Photographer Gilbert Echeverria About the cover Featuring: Angelina Cruz Shoot Coordinator: Damian Sanders Hair & Make Up: Valley Girl Beauty Emma “Vida” Ordóñez Designer: Escalady Jewelry: Douglass Designs Unlimited Cover photo by: TEEE Briscoe Art direction by Hristo Argirov Kovatliev Shot At Concrete Studios Los Angeles BOLDSWIM.COM OUT NOW ON MAGCLOUD.COM THE SOCIETY FASHION WEEK NEW YORK 2019 NEW YORK FASHION WEEK POWERED BY THE SOCIETY www.frozenclothing.com CIE FASHION MAGAZINE KAPRI SUN IG : _KAPRI.SUN Hair: Fatisha Griggs Make Up: NuNu Soto Photography: Steven Means CIE FASHION MAGAZINE EDITORIAL EXCLUSIVE KAPRI SUN IG : _KAPRI.SUN HAIR: FATISHA GRIGGS MAKE UP: NUNU SOTO PHOTOGRAPHY: STEVEN MEANS Coming from the land of year round sunshine, San Diego. I was born to 2 young parents who were fresh out of high school at the time. Like any family we had ups and downs. First 10 years of my life I gained 4 little brothers and always felt the need to be a positive role model for them. Fast forward to 2015... we lost our mom. She was only 45 years old, she had a stroke along with other heart complications. Here was the game changer. From her funeral I’ve met many of her friends from her past. I’ve learned things about my mom that I never knew. She dabbled a bit in to modeling back in the 80s before I was born. But never had a chance to pursue that dream after becoming a mother. -

Annual Scorecard.Xlsx

Worcestershire Camera Club PDI Competition No.2 Advanced Section 24th Nov 2015 Judge: Chris Baldwin Entry Author Title Score Aggregate 1 Bob Brierley Estuary Sunset 17 2 Bob Brierley Turning Hay 15 3 Bob Brierley Just for the fun 15 47 4 John Burrows Laid to Rest 17 5 John Burrows Glass Wing Butterfly 20 6 John Burrows Well Dressed Travellers 16 53 7 Andy Dawson Figure in the Window 16 8 Andy Dawson Hula Girl 17 9 Andy Dawson View from the Rialto Bridge Venice 16 49 10 Brian Eacock I Wanna Be A Model When I am Bigger 17 11 Brian Eacock Chapter House Stairs Wells Cathedral 16 12 Brian Eacock Bath time for the Bullfinches 16 49 13 Tony Gervis Reflecting on The Waves 19 14 Tony Gervis Double Exposure of Double O Arch 15 15 Tony Gervis A Grand Evening 17 51 16 Douglas Gregor Grey Crowned Crane 17 17 Douglas Gregor Hyena 16 18 Douglas Gregor Common Blue Damselflies 20 53 19 Malcolm Haynes The Survivor 17 20 Malcolm Haynes Moment of Decision 19 21 Malcolm Haynes The Pattern Maker 16 52 22 Alex Isaacs Still Life 18 23 Alex Isaacs Hidden Expression 16 24 Alex Isaacs Night Message 15 49 25 Judy Knights Red Sky in the Morning 19 26 Judy Knights Holy Island Blues 17 27 Judy Knights Perfect Reflections 16 52 28 Catherine Lane Homeward Bound 17 29 Catherine Lane Prayer Wheels 17 30 Catherine Lane Road to Nowhere 15 49 31 Darren Leeson Turkish Delight 16 32 Darren Leeson Iphoned Luv 18 33 Darren Leeson Expensive Compacts 14 48 34 Paul Mann Short Ride in a Fast Machine 17 35 Paul Mann The Aurora, The Plough, & Me 19 36 Paul Mann In Love in Paris 18 -

Musicals Go Undiscovered and Never Get the Productions They Deserve

SPRING 2020 PITCH BOOK At The Producer’s Perspective, we are on a mission to help 5000 shows get produced by 2025 and have curated this book of new work for your consideration. All too often, exciting new plays and musicals go undiscovered and never get the productions they deserve. So we wanted to provide an opportunity for theaters, producers, and organizations like yours to access information on new material just waiting to be discovered. The Pitch Book features over 100 new plays and musicals from creators across the country and provides you with a tagline and succinct pitch, as well as essential show and collaborator information for each project. We encourage you to peruse the pitches in this book and if you find a project that appeals to you, please feel free to reach out to the show directly or let us know by emailing [email protected]! To view the online version of our Pitch Book with clickable links and zooming capabilities, please visit www.theproducersperspective.com/producer-pitch-book now! 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS MUSICALS A CHRISTMAS CAROL (CUSTOMIZED FOR YOUR REGION) 5 A GREEN UNBRELLA 6 A SYMPHONY FOR PORTLAND 7 ACROSS THE AMAZONS 8 AFTER HAPPILY EVER AFTER 9 BAGELS! (THE MUSICAL) 10 BEGGARS & CHOOSERS, THE MUSICAL 12 BENDING TOWARDS THE LIGHT… A JAZZ NATIVITY 13 BETWIXT AND BETWEEN 14 BEYOND PERFECTION 15 BILLIONAIRE 16 BLANK SPACE THE MUSICAL (JUKEBOX MUSICAL WITH MUSIC & LYRICS BY TAYLOR SWIFT) 17 BRICKTOP: LEGEND OF THE JAZZ AGE 18 BROOKLYN BRIDGE EMILY’S STORY 20 BRUSH ARBOR REVIVAL 21 COME AND SEE 22 COMPANY MATTERS 23 DAISY AND THE WONDER WEEDS 24 DESERT ROSE 25 DOGS 26 EARTHBOUND (AN ELECTRONICA MUSICAL) 27 EMERALD MAN 28 EMERGENCY 29 EVANGELINE, A CURIOUS JOURNEY 30 GEORGINE 31 GERARDO BRU 32 GLINDA/MRS. -

Moon the Sickest Ambition Gravity Lipstick They Were Called Cowboys

december 2050 moon v gue gravity lipstick they the were sickest called ambition_ cowboys 02:15 so never forget yourself or what the scene stood for_a guy giving a loan to a bloke who knew he couldnt pay it_neither of them cared_ 02:16 liberal or j-ism? 02:15 authenticity is such a silly quest when u dial 02:17 then moonbile 02:20 cos youre worth it_connecting the universe with tools 2 move planets_call earth per month_99 03:12 99 already? this has a good 09:20 for 03:14 number of everything views 03:16 but little 2 no discussion_are u interested in starting a conversation? send me a sign_ 09:23 is possible for him who believes@Mark 9_23 12:12 for the slow people here is another analogy_the answer is simple_ okay_maybe the answer isnt simple_but its much more_simple than actually 12:12 doing it_ hit me 05:39 u cannot receive a sign or anything of life in 14:08 to the lovers of the 4inch feel and 05:39 the 14:10 4figure w/o real world heel_ 05:42 nothing_the spaced towns and maddening crowds? please do u receive me? they are all still_truly here_ 14:11 more shimmer_more luscious longer stronger fuller creamy_feel 21:42 2 few words_the moment u trip over more lines_things become complicated_ there is no longer a need 2 provide meaning_ 21:42 an atmosphere of 21:43 meaning is enough_ 21:44 send_ 2BZ4UQT 15:23 nope_i would get everything factchecked_but where are they from_i hope not other users_ 16:03 i wanna be a model posing as myself_its 16:04 more PFT_ 16:05 real 16:06 this 16:07 way 2041 זאמ החלצהב תרחסנ ,תירטנלפ גניפרומ Strong Cleansing -

Grow Taller by 3 to 6 Inches After Puberty!!!!! 5 Simple Exercises That Will Increase Your Height Naturally at Any Age

HubPages Grow taller by 3 to 6 inches after Puberty!!!!! 5 Simple exercises that will increase your height naturally at any age Grow taller by 3 to 6 inches after Puberty!!!!! 5 Simple exercises that will increase your height naturally at any age. I guarantee!!!! If you have a desire to grow tall and add a few inches to your height naturally through exercises, this is the Hub for you. Whatever your age may be, the exercises given in this article will help you gain extra height through natural exercises. These workouts are scientifically proven to increase height even after puberty, if done properly and regularly. By stretching and flexing your body, these exercises will stimulate your body to secrete HGH(Human Growth Hormone), which will increase your body height. 1. VERTICAL HANGING: This is a simple but an extremely effective stretching exercise which you can do at your home. All you need to have is a solid bar strong enough to hold an individual, fixed at least 7 feet above the ground such that the distance between your feet and the floor is atleast 4-6 inches. Hold your arms neither closer nor wider and start hanging. Hold as long as you can, and as you begin to tire, slowly swing back and forth and try to touch the ground with your feet. This will flex your spine and elongate it, so that you can add few inches to your height Make sure that you flex your spine while stretching, and not merely twisting your wrists Perform the Workout 3 times a week for optimal results 2. -

Annual Report 2008

Media Prima Berhad 532975 A Sri Pentas, No. 3, Persiaran Bandar Utama Bandar Utama, 47800 Petaling Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia www.mediaprima.com.my annual report 2008 FinanceAsia “thebrandlaureate” TV3 was named as one of Minority Shareholders Asia’s Best Companies 2008 Best Brands Electronic Media Malaysia Most Valuable Brands Watchdog Group Malaysia’s Best 2007-2008 (MMVB) by the Association of Corporate Governance Mid-Cap Company Accredited Advertising Agents Survey 2008-7th (Joint) Best Investor Relations Malaysia (4As) and Interbrand. (rank 7th) Best Corporate Governance (rank 8th) contents Notice of Annual General Meeting // 4 Statement Accompanying Notice of Annual General Meeting // 7 Calendar of Significant Events // 150 Our Profile // 8 Awards and Recognition // 159 Corporate Information // 9 Financial Statements // 165 Corporate Structure // 12 Directors’ Report // 166 Organisational Structure // 14 Income Statements // 171 Board of Directors’ Profile // 18 Balance Sheets // 173 Senior Management // 27 Statement of Changes in Equity // 175 Statement on Corporate Governance // 40 Cash Flow Statements // 177 Additional Compliance Information // 54 Summary of Significant Statement on Internal Control // 56 Accounting Policies // 179 Statement on Risk Management // 60 Notes to the Financial Statements // 195 Audit Committee Report // 64 Statement by Directors // 245 5-Year Financial Highlights // 70 Statutory Declaration // 245 Share Price Chart // 72 Report of the Auditors // 246 Viewership and Listenership Data // 73 Analysis of Shareholdings // 248 Chairman’s Statement // 76 List of Properties // 252 Corporate Responsibility // 84 Group Directory // 256 Review of Operations // 110 Proxy Form going beyond boundaries “The success of Media Prima is built on values that define the Group – passion and energy; creativity and financial discipline; professionalism and accountability - these are the foundations that we hold sacrosanct. -

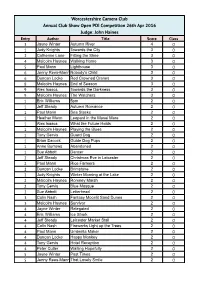

Annual Scorecard V4.Xlsx

Worcestershire Camera Club Annual Club Show Open PDI Competition 26th Apr 2016 Judge: John Haines Entry Author Title Score Class 3 Jayne Winter Autumn River 4 O 1 Judy Knights Towards the City 3 O 2 Catherine Lane Fitting the Shoe 3 O 4 Malcolm Haynes Walking Home 3 O 5 Paul Mann Lighthouse 3 O 6 Jenny Rees-Mann Nobody's Child 3 O 6 Duncan Locke Red Crowned Cranes 3 O 8 Malcolm Haynes End of Season 3 O 9 Alex Isaacs Towards the Darkness 3 O 9 Malcolm Haynes The Watchers 3 O 1 Eric Williams 5pm 2 O 1 Jeff Steady Autumn Romance 2 O 1 Paul Mann Sea Stacks 2 O 1 Heather Mann Leopard in the Masai Mara 2 O 1 Alex Isaacs What the Future Holds 2 O 1 Malcolm Haynes Playing the Blues 2 O 1 Tony Gervis Guard Dog 2 O 1 Brian Eacock Guide Dog Pups 2 O 1 Anne Burrows Abandoned 2 O 1 Sue Abbott Dancer 2 O 2 Jeff Steady Christmas Eve in Leicester 2 O 2 Paul Mann Rice Farmers 2 O 2 Duncan Locke Brimstone 2 O 2 Judy Knights Winter Morning at the Lake 2 O 2 Malcolm Haynes Romney Marsh 2 O 2 Tony Gervis Blue Mosque 2 O 2 Sue Abbott Letterhead 2 O 3 Colin Nash Fantasy Moonlit Sand Dunes 2 O 3 Malcolm Haynes Survivor 2 O 4 Jayne Winter Relegated 2 O 4 Eric Williams Ice Shark 2 O 4 Jeff Steady Leicester Market Stall 2 O 4 Colin Nash Fireworks Light up the Trees 2 O 4 Paul Mann Umbrella Maker 2 O 4 Duncan Locke Happy Monkey 2 O 4 Tony Gervis Hotel Reception 2 O 4 Peter Cutler Waiting Hopefully 2 O 5 Jayne Winter Past Times 2 O 5 Jenny Rees-Mann That Lovely Smile 2 O 5 Colin Nash Natasha 2 O 5 Malcolm Haynes Going for It 2 O 5 Tony Gervis Grand Canyon 2 O 5 Sue