A Sociolinguistic Survey (Ra/Rtt) of Ngie and Ngishe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

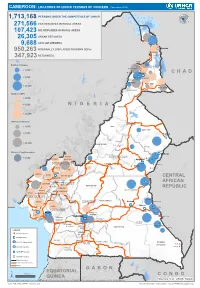

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

From Migrants to Nationals, from Nationals To

International Journal of Latest Engineering and Management Research (IJLEMR) ISSN: 2455-4847 www.ijlemr.com || Volume 03 - Issue 06 || June 2018 || PP. 10-19 From Nomads to Nationals, From Nationals to Undesirable Elements: The Case of the Mbororo/Fulani in North West Cameroon 1916-2008 A Historical Investigation Jabiru Muhammadou Amadou (Phd) Higher Teacher Training College Department of History The University of Yaounde 1 Abstract: The Fulani (Mbororo) are a minority group perceived as migrants and strangers by local North West groups who consider themselves their hosts and landlords. They are predominantly nomadic people located almost exclusively within the savannah zone of West and Central Africa. Their original homeland is said to be the Senegambia region. From Senegal, the Fulani continued their movement along side their cattle and headed to Northern Nigeria. Uthman Dan Fodio‟s 19th century jihad movement and epidemic outbreaks force them to move from Northern Nigeria to Northern Cameroon. From Northern Cameroon they moved down South and started penetrating the North West Region in the early 20th century. This article critically examines and considers the case of the Fulani in the North West Region of Cameroon and their recent claims to regional citizenship and minority status. The paper begins by presenting the migration, settlement and ultimate acquisition of the status of nationals by the nomadic cattle Fulani in North West Cameroon. It also analysis the difficulties encountered by this nomadic group to fully integrate themselves into the region. In the early 20th century (more precisely 1916) when they arrived the North West Region, they were warmly received by their hosts. -

N I G E R I a C H a D Central African Republic Congo

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (September 2020) ! PERSONNES RELEVANT DE Maïné-Soroa !Magaria LA COMPETENCE DU HCR (POCs) Geidam 1,951,731 Gashua ! ! CAR REFUGEES ING CurAi MEROON 306,113 ! LOGONE NIG REFUGEES IN CAMEROON ET CHARI !Hadejia 116,409 Jakusko ! U R B A N R E F U G E E S (CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND 27,173 NIGERIAN REFUGEE LIVING IN URBAN AREA ARE INCLUDED) Kousseri N'Djamena !Kano ASYLUM SEEKERS 9,332 Damaturu Maiduguri Potiskum 1,032,942 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSO! NS (IDPs) * RETURNEES * Waza 484,036 Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees MAYO SAVA Mora ! < 10,000 EXTRÊME-NORD Mokolo DIAMARÉ Biu < 50,000 ! Maroua ! Minawao MAYO Bauchi TSANAGA Yagoua ! Gom! be Mubi ! MAYO KANI !Deba MAYO DANAY < 75000 Kaele MAYO LOUTI !Jos Guider Number! of IDPs N I G E R I A Lafia !Ləre ! < 10,000 ! Yola < 50,000 ! BÉNOUÉ C H A D Jalingo > 75000 ! NORD Moundou Number of returnees ! !Lafia Poli Tchollire < 10,000 ! FARO MAYO REY < 50,000 Wukari ! ! Touboro !Makurdi Beke Chantier > 75000 FARO ET DÉO Tingere ! Beka Paoua Number of asylum seekers Ndip VINA < 10,000 Bocaranga ! ! Borgop Djohong Banyo ADAMAOUA Kounde NORD-OUEST Nkambe Ngam MENCHUM DJEREM Meiganga DONGA MANTUNG MAYO BANYO Tibati Gbatoua Wum BOYO MBÉRÉ Alhamdou !Bozoum Fundong Kumbo BUI CENTRAL Mbengwi MEZAM Ndop MOMO AFRICAN NGO Bamenda KETUNJIA OUEST MANYU Foumban REPUBLBICaoro BAMBOUTOS ! LEBIALEM Gado Mbouda NOUN Yoko Mamfe Dschang MIFI Bandjoun MBAM ET KIM LOM ET DJEREM Baham MENOUA KOUNG KHI KOUPÉ Bafang MANENGOUBA Bangangte Bangem HAUT NKAM Calabar NDÉ SUD-OUEST -

Centre De Yaoundé

AO/CBGI REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix –Travail – Patrie Peace – Work – Fatherland -------------- --------------- MINISTERE DE LA FONCTION PUBLIQUE MINISTRY OF THE PUBLIC SERVICE ET DE LA REFORME ADMINISTRATIVE AND ADMINISTRATIVE REFORM --------------- --------------- SECRETARIAT GENERAL SECRETARIAT GENERAL --------------- --------------- DIRECTION DU DEVELOPPEMENT DEPARTMENT OF STATE HUMAN DES RESSOURCES HUMAINES DE L’ETAT RESSOURCES DEVELOPMENT --------------- --------------- SOUS-DIRECTION DES CONCOURS SUB DEPARTMENT OF EXAMINATIONS ------------------ -------------------- CONCOURS DIRECT POUR LE RECRUTEMENT DE 100 CONTRÔLEURS-ADJOINTS DES RÉGIES FINANCIÈRES (TRÉSOR) SESSION 2020 CENTRE DE YAOUNDÉ LISTE DES CANDIDATS AUTORISÉS À SUBIR LES ÉPREUVES ÉCRITES DU 05 SEPTEMBRE 2020 CANDIDATS ANGLOPHONES/ANGLOPHONE CANDIDATES RÉGION DÉPARTEMENT NO MATRICULE NOMS ET PRÉNOMS DATE ET LIEU DE NAISSANCE SEXE LANGUE D’ORIGINE D’ORIGINE 6871. CATR18208 ABAMA ABAMA JEAN JOEL 15/10/2001 A YAOUNDE M CE MBAM ET INOUBOU A 6872. CATR17043 ABANE DORIS AKOH 06/06/2000 A BAMUNKA F SW MANYU A 6873. CATR15886 ABBO MAMA ORNELLA AUDE 22/07/1999 A YAOUNDE F AD VINA A 6874. CATR04130 ABDOULLAH OUSMANOU ISMAILA 17/07/1993 A YAOUNDE M AD DJEREM A 6875. CATR11935 ABDOURAHMANE YAOUBA 28/04/1997 A MOKOLO M EN MAYO TSANAGA A MINFOPRA/SG/DDRHE/SDC|Liste générale des candidats Contrôleurs-Adjoints des Régies Financières (Trésor), session 2020_Yaoundé Page 190 6876. CATR14165 ABENA BOULA PHILOMENE ESTHER 20/06/1998 A DOUALA F CE LEKIE A 6877. CATR16644 ABESSOLO HUGUETTE RAÏSSA 28/01/2000 A YAOUNDE F SU DJA ET LOBO A 6878. CATR11194 ABIA ALAIN AGWAYIER 24/12/1996 A EKONA FAKO M NW MOMO A 6879. CATR00296 ABIMNUI NGECHE ESTHER 29/03/1991 A BAMBILI F NW MEZAM A 6880. -

Joshua Osih President

Joshua Osih President THE STRENGTH OF OUR DIVERSITY PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION 2018 JOSHUA OSIH | THE STRENGTH OF OUR DIVERSITY | P . 1 MY CONTRACT WITH THE NATION Build a new Cameroon through determination, duty to act and innovation! I decided to run in the presidential election of October 7th to give the youth, who constitute the vast majority of our population, the opportunity to escape the despair that has gripped them for more than three decades now, to finally assume responsibility for the future direction of our highly endowed nation. The time has come for our youth to rise in their numbers in unison and take control of their destiny and stop the I have decided to run in the presidential nation’s descent into the abyss. They election on October 7th. This decision, must and can put Cameroon back on taken after a great deal of thought, the tracks of progress. Thirty-six years arose from several challenges we of selfish rule by an irresponsible have all faced. These crystalized into and corrupt regime have brought an a single resolution: We must redeem otherwise prosperous Cameroonian Cameroon from the abyss of thirty-six nation to its knees. The very basic years of low performance, curb the elements of statecraft have all but negative instinct of conserving power disappeared and the citizenry is at all cost and save the collapsing caught in a maelstrom. As a nation, system from further degradation. I we can no longer afford adequate have therefore been moved to run medical treatment, nor can we provide for in the presidential election of quality education for our children. -

206 Villages Burnt in the North West and South West Regions

CHRDA Email: [email protected] Website: www.chrda.org Cameroon: The Anglophone Crisis 206 Villages burnt in the North West and South West Regions April 2019 SUMMARY The Center for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa (CHRDA) has analyzed data from local sources and identified 206 villages that have been partially, or completely burnt since the beginning of the immediate crisis in the Anglophone regions. Cameroon is a nation sliding into civil war in Africa. In 2016, English- speaking lawyers, teachers, students and civil society expressed “This act of burning legitimate grievances to the Cameroonian government. Peaceful protests villages is in breach of subsequently turned deadly following governments actions to prevent classical common the expression of speech and assembly. Government forces shot peaceful article 3 to the Four protesters, wounded many and killed several. Geneva Convention 1949 and the To the dismay of the national, regional and international communities, Additional Protocol II the Cameroon government began arresting activists and leaders to the same including CHRDA’s Founder and CEO, Barrister Agbor Balla, the then Convention dealing President of the now banned Anglophone Consortium. Internet was shut with the non- down for three months and all forms of dissent were stifled, forcing international conflicts. hundreds into exile. Also, the burning of In August 2017, President Paul Biya of Cameroon ordered the release of villages is in breach of several detainees, but avoided dialogue, prompting mass protests in national and September 2017 with an estimated 500,000 people on the streets of international human various cities, towns and villages. The government’s response was a rights norms and the brutal crackdown which led to a declaration of independence on October host of other laws” 1, 2017. -

Assessment of Prunus Africana Bark Exploitation Methods and Sustainable Exploitation in the South West, North-West and Adamaoua Regions of Cameroon

GCP/RAF/408/EC « MOBILISATION ET RENFORCEMENT DES CAPACITES DES PETITES ET MOYENNES ENTREPRISES IMPLIQUEES DANS LES FILIERES DES PRODUITS FORESTIERS NON LIGNEUX EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE » Assessment of Prunus africana bark exploitation methods and sustainable exploitation in the South west, North-West and Adamaoua regions of Cameroon CIFOR Philip Fonju Nkeng, Verina Ingram, Abdon Awono February 2010 Avec l‟appui financier de la Commission Européenne Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... i ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................... ii Abstract .................................................................................................................. iii 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Problem statement ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 Research questions .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Objectives ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Importance of the study ................................................................................... 3 2: Literature Review ................................................................................................. -

Masculinity and Female Resistance in the Rice Economy in Meteh/Menchum Valley Bu, North West Cameroon, 1953 – 2005

Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Volume 15, No.7, 2013) ISSN: 1520-5509 Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania MASCULINITY AND FEMALE RESISTANCE IN THE RICE ECONOMY IN METEH/MENCHUM VALLEY BU, NORTH WEST CAMEROON, 1953 – 2005 Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon ABSTRACT Male chauvinism and female reaction in the rice economy in Bu, Menchum Division of North West Cameroon is the subject of this investigation. The greater focus of this paper is how and why this phobia has lessened over the years in favour of female dominion over the rice economy. The point d’appui of the masculine management of the economy and the accentuating forces which have militated against their continuous domination of women in the rice sector have been probed into. Incongruous with the situation hitherto, women have farms of their own bought with their own money accumulated from other economic activities. In addition, they now employ the services of men to execute some defined tasks in the rice economy. From the copious data consulted on the rice economy and related economic endeavours, it is a truism that be it collectively and/or individually, men and women in Bu are responding willingly or not, to the changing power relations between them in the rice economy with implications for sustainable development. Keywords: Masculinity, Female Resistance, Rice Economy, Cameroon, Sustainability 115 INTRODUCTION: RELEVANCE OF STUDY AND CONCEPT OF MASCULINITY Rice is a staple food crop in Cameroon like elsewhere in Africa and other parts of the world. It has become increasingly important part of African diets especially West Africa and where local production has been insufficient due to limited access to credit (Akinbode, 2013, p. -

MBENGWI COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT PLAN Email: [email protected] Kumbo, the ………………………

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON PAIX- TRAVAIL- PATRIE PEACE- WORK-FAHERLAND ----------------------------- ----------------------------- MINISTERE DE L’ADMINISTRATION MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL ADMINSTRATION TERRITORIALE ET AND DECENTRALISATION DECENTRALISATION ----------------------------- ----------------------------- NORTH WEST REGION REGION DU NORD OUEST ----------------------------- ----------------------------- MOMO DIVISION DEPARTEMENT DE MOMO ----------------------------- -------------------------- MBENGWI COUNCIL COMMUNE DE MBENGWI ----------------------------- ------------------------------- [email protected] Kumbo, the ………………………. MBENGWI COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT PLAN Email: [email protected] Kumbo, the ………………………. Elaborated with the Technical and Financial Support of the National Community Driven Development Program (PNDP) March 2012 i MBENGWI COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT PLAN Elaborated and submitted by: Sustainable Integrated Balanced Development Foundation (SIBADEF), P.O.BOX 677, Bamenda, N.W.R, Cameroon, Tel: (237) 70 68 86 91 /98 40 16 90 / 33 07 32 01, E-mail: [email protected] March 2012 ii Table of Content Topic Page 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Context and Justification.............................................................................................. 1 1.2 CDP objectives............................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Structure of the work................................................................................................... -

Non-Commercial Use Only

Journal of Public Health in Africa 2011 ; volume 2:e10 Social stigma as an epidemio- lack of self-esteem, tribal stigma and complete rejection by society. From the 480 structured Correspondence: Dr. Dickson S. Nsagha, logical determinant for leprosy questionnaires administered, there were over- Department of Public Health and Hygiene, elimination in Cameroon all positive attitudes to lepers among the study Medicine Programme, Faculty of Health Sciences, population and within the divisions (P=0.0). University of Buea, PO Box 63, Buea, Cameroon. Dickson S. Nsagha,1,2 The proportion of participants that felt sympa- Tel. +237. 77499429.E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Anne-Cécile Z.K. Bissek,3 thetic with deformed lepers was 78.1% [95% 4 confidence interval (CI): 74.4-81.8%] from a Sarah M. Nsagha, Key words: leprosy, social stigma, attitudes, elim- Anna L. Njunda,5 total of 480. Three hundred and ninety nine ination, Cameroon. Jules C.N. Assob,6 (83.1%) respondents indicated that they could Earnest N. Tabah,7 share a meal or drink at the same table with a Acknowledgements: the authors are grateful to Elijah A. Bamgboye,2 deformed leper (95% CI: 79.7-86.5%). Four Mr. Nsagha BN, Mr. Nsagha IG and Late Papa hundred and three (83.9%) participants indi- James Nsagha, who sponsored this study. The Alain Bankole O.O. Oyediran,2 cated that they could have a handshake and authors also thank Mr. Agyngi CT & Mr. Ideng DA Peter F. Nde,1 embrace a deformed leper (95% CI: 80.7- of the Benakuma Health Center; Mr. -

Cameroon Page 1 of 27

Cameroon Page 1 of 27 Cameroon Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2001 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 4, 2002 Cameroon is a republic dominated by a strong presidency. Since independence a single party, now called the Cameroon People's Democratic Movement (CPDM), has remained in power. In 1997 CPDM leader Paul Biya won reelection as President in an election boycotted by the three main opposition parties, marred by a wide range of procedural flaws, and generally considered by observers not to be free and fair. The 1997 legislative elections, which were dominated by the CPDM, were flawed by numerous irregularities and generally considered not free nor fair by international and local observers. The President retains the power to control legislation or to rule by decree. In the National Assembly, government bills take precedence over other bills, and no bills other than government bills have been enacted since 1991, although the Assembly sometimes has not enacted legislation proposed by the Government. The President has used his control of the legislature to change the Constitution. The 1996 Constitution lengthened the President's term of office to 7 years, while continuing to allow Biya to run for a fourth consecutive term in 1997 and making him eligible to run for one more 7-year term in 2004. In 2000 the Government began discussion on an action plan to create the decentralized institutions envisioned in the 1996 Constitution, such as a partially elected senate, elected regional councils, and a more independent judiciary; however, none of the plans had been executed by year's end.