The Self-Made Man, Conspicuous Consumption, and Competitive Masculinity in Gilded Age New York City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X********X************************************************** * Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made * from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 302 264 IR 052 601 AUTHOR Buckingham, Betty Jo, Ed. TITLE Iowa and Some Iowans. A Bibliography for Schools and Libraries. Third Edition. INSTITUTION Iowa State Dept. of Education, Des Moines. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 312p.; Fcr a supplement to the second edition, see ED 227 842. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibllographies; *Authors; Books; Directories; Elementary Secondary Education; Fiction; History Instruction; Learning Resources Centers; *Local Color Writing; *Local History; Media Specialists; Nonfiction; School Libraries; *State History; United States History; United States Literature IDENTIFIERS *Iowa ABSTRACT Prepared primarily by the Iowa State Department of Education, this annotated bibliography of materials by Iowans or about Iowans is a revised tAird edition of the original 1969 publication. It both combines and expands the scope of the two major sections of previous editions, i.e., Iowan listory and literature, and out-of-print materials are included if judged to be of sufficient interest. Nonfiction materials are listed by Dewey subject classification and fiction in alphabetical order by author/artist. Biographies and autobiographies are entered under the subject of the work or in the 920s. Each entry includes the author(s), title, bibliographic information, interest and reading levels, cataloging information, and an annotation. Author, title, and subject indexes are provided, as well as a list of the people indicated in the bibliography who were born or have resided in Iowa or who were or are considered to be Iowan authors, musicians, artists, or other Iowan creators. Directories of periodicals and annuals, selected sources of Iowa government documents of general interest, and publishers and producers are also provided. -

Make Them Like You

Title: Diamond Jim Brady: Prince of the Gilded Age Author: H. Paul Jeffers ISBN: 0-471-39102-6 1 Make Them Like You qr N THE MIND OF Daniel Brady in the summer of 1856, the I most important things in life were the customers who bought beer at three cents a stein in his waterfront saloon on the corner of Cedar and West streets on New York’s Lower West Side, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Democratic Party. Consequently, when Dan’s second son was born on the twelfth of August, the beer flowed freely. Presently the parish priest was informed that the boy he would be called on to bap- tize had been named after the Democratic nominee for presi- dent of the United States. If the father of the newborn had his way, James Buchanan Brady and his older brother (their father’s namesake) would follow him in the saloon business. The first years of Jim’s life, therefore, were filled with the voices of hardworking, hard- drinking, mostly Irish longshoremen and teamsters who lived nearby. They earned their wages from the ships whose masts resembled a leaf-bare forest on the edge of the Hudson River that reached from the tip of Manhattan north to the human wasteland of spirit-crushing tenements called Hell’s Kitchen. A dozen years before Jim was born, England’s most famous author, Charles Dickens, had toured the New York waterfront and found the bowsprits of hundreds of ships stretching across the waterside streets and almost thrusting themselves into the 7 8 DIAMOND JIM BRADY windows of adjacent buildings. -

Untitled, It Is Impossible to Know

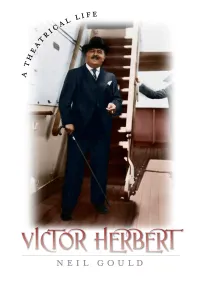

VICTOR HERBERT ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE i ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE ii VICTOR HERBERT A Theatrical Life C:>A<DJA9 C:>A<DJA9 ;DG9=6BJC>K:GH>INEG:HH New York ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iii Copyright ᭧ 2008 Neil Gould All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gould, Neil, 1943– Victor Herbert : a theatrical life / Neil Gould.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2871-3 (cloth) 1. Herbert, Victor, 1859–1924. 2. Composers—United States—Biography. I. Title. ML410.H52G68 2008 780.92—dc22 [B] 2008003059 Printed in the United States of America First edition Quotation from H. L. Mencken reprinted by permission of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore, Maryland, in accordance with the terms of Mr. Mencken’s bequest. Quotations from ‘‘Yesterthoughts,’’ the reminiscences of Frederick Stahlberg, by kind permission of the Trustees of Yale University. Quotations from Victor Herbert—Lee and J.J. Shubert correspondence, courtesy of Shubert Archive, N.Y. ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iv ‘‘Crazy’’ John Baldwin, Teacher, Mentor, Friend Herbert P. Jacoby, Esq., Almus pater ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE v ................ -

Iowa and Some Iowans

Iowa and Some Iowans Fourth Edition, 1996 IOWA AND SOME IOWANS A Bibliography for Schools and Libraries Edited by Betty Jo Buckingham with assistance from Lucille Lettow, Pam Pilcher, and Nancy Haigh o Fourth Edition Iowa Department of Education and the Iowa Educational Media Association 1996 State of Iowa DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Grimes State Office Building Des Moines, Iowa 50319-0146 STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION Corine A. Hadley, President, Newton C. W. Callison, Burlington, Vice President Susan J. Clouser, Johnston Gregory A. Forristall, Macedonia Sally J. Frudden, Charles City Charlene R. Fulton, Cherokee Gregory D. McClain, Cedar Falls Gene E. Vincent, Carroll ADMINISTRATION Ted Stilwill, Director and Executive Officer of the State Board of Education Dwight R. Carlson, Assistant to Director Gail Sullivan, Chief of Policy and Planning Division of Elementary and Secondary Education Judy Jeffrey, Administrator Debra Van Gorp, Chief, Bureau of Administration, Instruction and School Improvement Lory Nels Johnson, Consultant, English Language Arts/Reading Betty Jo Buckingham, Consultant, Educational Media, Retired Division of Library Services Sharman Smith, Administrator Nancy Haigh It is the policy of the Iowa Department of Education not to discriminate on the basis of race, religion, national origin, sex, age, or disability. The Department provides civil rights technical assistance to public school districts, nonpublic schools, area education agencies and community colleges to help them eliminate discrimination in their educational programs, activities, or employment. For assistance, contact the Bureau of School Administration and Accreditation, Iowa Department of Education. Printing funded in part by the Iowa Educational Media Association and by LSCA, Title I. ii PREFACE Developing understanding and appreciation of the history, the natural heritage, the tradition, the literature and the art of Iowa should be one of the goals of school and libraries in the state. -

German Cookbook

German Cookbook BY JAN MITCHELL The Story and the Favorite Dishes of America's Most Famous German Restaurant WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND ILLUSTRATIONS BY LUDWIG BEMELMANS Doubleday & Company, Inc., Garden City, New York To the Most Wonderful People in the World My Patrons Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 52-5764 Down Where the Wurzburger Flows, copyright, 1902, by Harry Von Tilier Music Pub. Co. Copyright renewed, 1929, and assigned to Harry Von Tilzer Music Pub. Co. Used by permission of copyright proprietor. Copyright, 1952, by Leonard Jan Mitchell AH rights reserved including the right to reproduce this book or portions therefrom in any form. Printed in the United States of America Designed by Alrna Reese Cardi CONTENTS INTRODUCTION BY LUDWIG BEMELMANS, 11 THE STORY OF LUCHOW'S, 17 HOW WE COOK AT LUCHOW'S, 37 1. Appetizers, 38 2 . Soupst 48 3. Fish and Shellfish, 59 4. Poultry and Game Birds, 73 5. Meats and Game, 92 6. Cheese and Eggs, 140 7. Dumplings and Noodles, 144 8. Salads and Salad Dressings, 150 9. Vegetables, 157 10. Sauces, 171 11, Desserts, 182 THE WINES, BEER, AND FESTIVALS AT LUCHOW'S OR Down Where the Wurzburger Flows, 207 INDEX, 215 INTRODUCTION BY LUDWIG BEMELMANS *The German dictionary defines the word "gemutlick" as good- natured, jolly, agreeable, cheerful, hearty, simple and affection- ate, full of feeling, comfortable, cozy, snug; and "Gemutlichkeit" as a state of mind, an easygoing disposition, good nature, genial- ity, pleasantness, a freedom from pecuniary or political cares, comfortableness. Of the remaining few New York places that can call them- selves restaurants, Liichow's triumphs in Gemutlichkeit. -

Picture Show Annual (1941)

S; yVivvwy U^vV-XC* VwvV*!Lt *Lov<- ^Wi , JCCC -3«c. i c^L*rO. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/pictureshowannua00amal_14 im&m Robert Young and Helen Gilbert in “ Florian. On the Cover : Bette Davis and Errol Flynn in “ The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex." r think most cinemagoers favour the idea of the revival of favourite films, for to those who saw the originals there are the memories of the past and also comparisons between the old produc- tions and the new, particularly in respect to those that have been made both as a silent and a talkie. To the newer generation of the cinema public there is interest in comparing the old-time screen stones with the modem ones. “ ” To be technically correct, revival is not the right word, for the old favourites are re-made, but in the majority of cases the original film is not altered to any great extent so far as the story is concerned, though the introduction of spoken dialogue must necessarily be more expensive them that recorded by the printed sub-title of the silent picture. On the whole, the re-making of popular pictures is done so well that it is deserving of the highest praise, but there is one criticism I have to make. I think it is a great mistake to alter the original title. Take a person who saw the original film passing by a cinema which is showing a revival under a new title. There is nothing to indicate that this is a new version of an old favourite, and such a person might well walk on to another cinema, missing what would have been a real treat. -

Authentic Original Lillian Russell 1890 Recipe Collection from the New York City Theater District

Feast on Gay Nineties Recipes from My Grandparents Elite Broadway New York City Restaurants Circa 1890. Authentic Original Lillian Russell 1890 Recipe Collection from the New York City Theater District Eat the Same Special Meals Prepared for Lillian Russell and "Diamond Jim" Brady. Compiled by E. J. Gelb Page 1 of 108 © Copyright 2006, Gelb Organization, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. Feast on Gay Nineties Recipes from My Grandparents Elite Broadway New York City Restaurants Circa 1890. Feast on the authentic recipes that were created for gourmands and personalities, especially Tony Pastor, Lillian Russell, J. B. "Diamond Jim" Brady, Thomas Edison, Marshall Field, Adolphus "Anheiser - Budweiser" Busch, Victor Herbert, and Sam Schubert. This was New York City at a renaissance of culture.. "The 1890's", "Gilded Age" or the "Naughty Nineties", if you prefer. This is a computerized electronic book (eBook). This method of distribution is very cost effective and saves publishing costs; therefore the cost that we can offer this book to you is very reasonable. The book consists of links and these links are ALL UNDERLINED AND IN BLUE. Clicking on these links will take you directly to a recipe or author note. Thus you can not only find a recipe quickly but you can also make a print out of it by clicking on the PRINT icon on your computer. If have any questions about the recipes, please contact the author at [email protected]. To order additional copies of this book please visit URL: www.gelb.com/gayninetiescookbook/ All text © Copyright 2006 by Gelb Organization, L.L.C. -

Bescennaja Golova Slavnyj Malyj

revealed the drama of the aging jockey ruled out the commonly used, forced style of comedy that would have distracted the viewer from the heart of the story. In December of 1940, the film was ap- proved by the main control authority, but Mosfil’m, without any reason, suspended its release. The enthusiastic words and praise made in public by Šklovskij, Don- skoj and Judin had no effect. And just as vain was the letter to Mikhail Romm’s Studios, which contemplated some slight changes so that the film could be screened. As of today, documents regard- ing its banning are still missing, but it is known that Ždanov included the title among films with a suspicious ideological bent in a speech to the Cinematography Committee in May of 1941. Undoubtedly, the authors paid for the natural way they depicted the racetrack, which could be Il vecchio fantino tolerated in real life but was not viewed as an appropriate image of Soviet life for the screen. menzionato solo in appendice. L’uscita Odnaždy nocˇ’ju was only mentioned in the Released in 1959, the film went entirely dei Boevye kinosborniki [Cineraccolte di appendix. Boevye kinosborniki [War Film unnoticed due to the changes in the times guerra] proseguì per un intero anno fino Collections] continued to be released for and the interest in new forms of cinematic alla ripresa della regolare produzione di a whole year until feature film production expression. lungometraggi nei luoghi dell’evacuazio- began again in the previously evacuated ne. Essi anticiparono le linee su cui si zones. -

Nobody Asked Me, But…No. 176: Hotel History: the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, New York City; My Five Published Hotel Books April 3, 2017 6:52Am

Nobody Asked Me, But…No. 176: Hotel History: The Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, New York City; My Five Published Hotel Books April 3, 2017 6:52am Share This Link on FacebookShare This on TwitterShare This on Google+in Share By Stanley Turkel, CMHS Hotel History: The Waldorf-Astoria Hotel On March 7, 2017 the Landmarks Preservation Commission voted to protect the interior Art Deco details of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel whose exterior is already landmarked. In 2015, Chinaʼs Anbang Insurance Group bought the Waldorf Astoria for nearly $2 billion from Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc. Anbang has just closed the hotel for a complete makeover involving conversion of hundreds of guestrooms into privately-owned condominiums. In my book “Hotel Mavens: Lucius M. Boomer, George C. Boldt and Oscar of the Waldorf” (AuthorHouse 2014), I tell the fascinating story of the construction of the new Waldorf-Astoria from 1929-1931, the hoteliers who created it, the singular design and the remarkable guest list. On December 20, 1928, the Boomer-duPont Properties Corporation announced that the original Waldorf-Astoria (designed by Henry J. Hardenbergh) on Fifth Avenue and Thirty-Fourth Street would be demolished. They sold the hotel to real estate developers for $13.5 million to construct the Empire State Building and Boomer was able to obtain the rights to the name Waldorf-Astoria for the payment of one dollar. The new Waldorf-Astoria was to be built on an entire block leased from the New York Central Railroad between Park and Lexington Avenues between Forty-ninth and Fiftieth Streets. Even before the original Waldorf-Astoria closed down for demolition, Lucius Boomer asked the famous architectural firm of Schultze & Weaver to begin planning a new, larger Waldorf-Astoria. -

6005853203.Pdf

ffirs.qxd 6/27/01 2:55 PM Page i Diamond Jim Brady ffirs.qxd 6/27/01 2:55 PM Page ii ffirs.qxd 6/27/01 2:55 PM Page iii Diamond Jim Brady qr Prince of the Gilded Age H. Paul Jeffers John Wiley & Sons, Inc. New York • Chichester • Weinheim • Brisbane • Singapore • Toronto Copyright © 2001 by H. Paul Jeffers. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Sec- tion 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Cen- ter, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4744. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 605 Third Ave- nue, New York, NY 10158-0012, (212) 850-6011, fax (212) 850-6008, email: [email protected]. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative informa- tion in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understand- ing that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. This title is also available in print as ISBN 0-471-39102-6. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.Wiley.com ffirs.qxd 6/27/01 2:55 PM Page v To Dr. -

Guide to the UNLV University Libraries Menu Collection

Guide to the UNLV University Libraries Menu Collection This finding aid was created by Mary Anilao, Chriziel Childers, Kyle Gagnon, Sarah Jones, Paola Landaverde, Angela Moor, and Lauren Paljusaj. This copy was published on August 04, 2021. Persistent URL for this finding aid: http://n2t.net/ark:/62930/f1s94v © 2021 The Regents of the University of Nevada. All rights reserved. University of Nevada, Las Vegas. University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives. Box 457010 4505 S. Maryland Parkway Las Vegas, Nevada 89154-7010 [email protected] Guide to the UNLV University Libraries Menu Collection Table of Contents Summary Information ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Historical Note ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Contents Note ................................................................................................................................ 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................. 5 Related Materials ............................................................................................................................................