Political Catholicism in Spain's Second Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plano De Los Transportes Del Distrito De Usera

AEROPUERTO T4 C-1 CHAMARTÍN C-2 EL ESCORIAL C-3 ALCOBENDAS-SAN. SEB. REYES/COLMENAR VIEJO C-4 PRÍNCIPE PÍO C-7 FUENTE DE LA MORAN801 C-7 VILLALBA-EL ESCORIAL/CERCEDILLAN805 C-8 VILLALBA C-10 Plano de los transportes delN806 distrito de Usera Corrala Calle Julián COLONIA ATOCHA 36 41 C1 3 5 ALAMEDA DE OSUNA Calle Ribera M1 SEVILLA MONCLOA M1 SEVILLA 351 352 353 AVDA. FELIPE II 152 C1 CIRCULAR PAVONES 32 PZA. MANUEL 143 CIRCULAR 138 PZA. ESPAÑA ÓPERA 25 MANZANARES 60 60 3 36 41 E1 PINAR DE 1 6 336 148 C Centro de Arte C s C 19 PZA. DE CATALUÑA BECERRA 50 C-1 PRÍNCIPE PÍO 18 DIEGO DE LEÓN 56 156 Calle PTA. DEL SOL . Embajadores e 27 CHAMARTÍN C2 CIRCULAR 35 n Reina Sofía J 331 N301 N302 138 a a A D B E o G H I Athos 62 i C1 N401 32 Centro CIRCULAR N16 l is l l t l F 119 o v 337 l PRÍNCIPE PÍO 62 N26 14 o C-7 C2 S e 32 Conde e o PRÍNCIPE PÍO P e Atocha Renfe C2 t 17 l r 63 K 32 a C F d E P PMesón de v 59 N9 Calle Cobos de Segovia C2 Comercial eña de CIRCULAR d e 23 a Calle 351 352 353 n r lv 50 r r EMBAJADORES Calle 138 ALUCHE ú i Jardín Avenida del Mediterráneo 6 333 332 N9 p M ancia e e e N402 de Casal 334 S a COLONIA 5 C1 32 a C-10 VILLALBA Puerta M1 1 Paseo e lle S V 26 tin 339 all M1 a ris Plaza S C Tropical C. -

'Neither God Nor Monster': Antonio Maura and the Failure of Conservative Reformism in Restoration Spain (1893–1923)

María Jesús González ‘Neither God Nor Monster’: Antonio Maura and the Failure of Conservative Reformism in Restoration Spain (1893–1923) ‘Would you please tell me which way I ought to go from here?’, said Alice. ‘That depends on where you want to get to’, said the cat. (Alice in Wonderland, London, The Nonesuch Press, 1939, p. 64) During the summer of 1903, a Spanish republican deputy and journalist, Luis Morote, visited the summer watering-holes of a number of eminent Spanish politicians. Of the resulting inter- views — published as El pulso de España1 — two have assumed a symbolic value of special significance. When Morote interviewed the Conservative politician Eduardo Dato, Dato was on the terrace of a luxury hotel in San Sebastián, talking with his friends, the cream of the aristocracy. It was in that idyllic place that Dato declared his great interest in social reforms as the best way to avoid any threat to the stability of the political system. He was convinced that nobody would find the necessary support for political revolution in Spain. The real danger lay in social revolution.2 Morote wrote that Antonio Maura, who was at his Santander residence, went into a sort of ‘mystic monologue’, talking enthu- siastically about democracy, the treasure of national energy that was hidden in the people, the absence of middle classes and the mission of politicians: that the people should participate, and that every field in politics should be worked at and dignified.3 Two Conservative politicians, two different approaches, two different paths towards an uncertain destination: one of them patching up holes in the system and the liberal parliamentary monarchic regime in its most pressing social requirements, the European History Quarterly Copyright © 2002 SAGE Publications, London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi, Vol. -

España Y La Primera Guerra Mundial

«NO FUE AQUELLO SOLAMENTE UNA GUERRA, FUE UNA REVOLUCIÓN»: ESPAÑA Y LA PRIMERA GUERRA MUNDIAL MIGUEL MARTORELL LINARES Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia [email protected] (Recepción: 20/11/2010; Revisión: 12/01/2011; Aceptación: 08/04/2011; Publicación: 10/10/2011) 1. Neutralidad.—2. descoNcierto.—3. orgía de gaNaNcias.—4. el estado, a la zaga.—5. crisis ecoNómica y otras oportuNidades.—6. movilizacióN.— 7. re volucióN.—8. el liberalismo, eN la eNcrucijada.—9. coN tra rre vo lu cióN.—10. dic tadura.—11. bibliografía resumeN En 1937 Alejandro Lerroux escribió, en referencia a la Primera Guerra Mundial, que «no fue aquello solamente una guerra, fue una revolución». Años después de que terminara la contienda muchos viejos liberales compartían una percepción semejante y consideraban que la Gran Guerra representó el principio del fin del orden político, eco- nómico y cultural liberal que había imperado en Europa a lo largo del siglo xix. Partien- do de dicha reflexión, este artículo analiza las repercusiones de la Primera Guerra Mundial sobre la economía, la sociedad y la política españolas, su influencia en el au- mento de la conflictividad social en los años de posguerra, cómo contribuyó a debilitar el sistema político de la Restauración y cómo alentó a quienes pretendían acabar con dicho sistema, cómo reforzó el discurso antiliberal en las derechas y cómo contribuyó a crear el ambiente en el que se fraguó el golpe de Estado de Primo de Rivera, en sep- tiembre de 1923. Palabras clave: España, siglo xx, política, economía, Primera Guerra Mundial Historia y Política ISSN: 1575-0361, núm. -

Joint Action on Chronic Diseases & Promoting Healthy Ageing Across the Life Cycle

Joint Action on Chronic Diseases & Promoting Healthy Ageing across the Life Cycle GOOD PRACTICE EXAMPLES IN HEALTH PROMOTION & PRIMARY PREVENTION IN CHRONIC DISEASE PREVENTION ANNEX 2 of 307 Contents Pre-natal environment, Early childhood, Childhood & Adolescence An Intervention for Obese Pregnant Women - Sweden ................................................................................. 4 ToyBox Intervention - Greece ......................................................................................................................... 7 School Fruit Scheme strategy for the 2010–2013 school years - Lithuania ................................................. 13 Promotion of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption among Schoolchildren, ‘PROGREENS’ - Bulgaria ............ 18 'Let’s Take on Childhood Obesity’ - Ireland .................................................................................................. 24 ‘Health and Wellbeing One of Six Fundamental Pillars of Education’ - Iceland .......................................... 38 Young People at a Healthy Weight, ´JOGG´ - Netherlands .......................................................................... 43 Dutch Obesity Intervention in Teenagers, ‘DOiT’ - Netherlands .................................................................. 54 Active School Flag - Ireland .......................................................................................................................... 63 National Network of Health Promoting Schools - Lithuania ...................................................................... -

USA OIL ASSOCIATION (NAOOA) Building C NEPTUNE NJ 07753

11.12.2017 LISTE DES EXPORTATEURS ET IMPORTATEURS D’HUILES D’OLIVE, D’HUILES DE GRIGNONS D’OLIVE ET D’OLIVES DE TABLE LIST OF EXPORTERS AND IMPORTERS OF OLIVE OILS, OLIVE-POMACE OILS AND TABLE OLIVES UNITED STATES OF AMERICA/ÉTATS-UNIS D’AMÉRIQUE ENTITÉ/BODY ADRESSE/ADDRESS PAYS/ WEBSITE COUNTRY NORTH AMERICAN OLIVE 3301 Route 66 – Suite 205, USA www.naooa.org OIL ASSOCIATION (NAOOA) Building C NEPTUNE NJ 07753 ACEITES BORGES PONT, S.A. Avda. J. Trepat s/n SPAIN 25300 TARREGA (Lleida) ACEITES DEL SUR, S.A. Ctra. Sevilla-Cádiz, Km. SPAIN www.acesur.com 550,6 41700 DOS HERMANAS (Sevilla) ACEITES TOLEDO S.A. Paseo Pintor Rosales, 4 y 6 SPAIN www.aceitestoledo.com 28008 MADRID ACEITUNAS DE MESA S.L. Antiguo Camino de Sevilla SPAIN s/n 41840 PILAS (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS GUADALQUIVIR Camino Alcoba, s/n SPAIN www.agolives.com S.L. 41530 MORON DE LA FRONTERA (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS MONTEGIL, S.L. Eduardo Dato, 9 SPAIN www.aceitunasmontegil.es 41530 MORON DE LA FRONTERA (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS RUMARIN S.A. Calle Pedro Crespo, 79 SPAIN 41510 MAIRENA DEL ALCOR (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS SEVILLANAS Calle Párroco Vicente Moya, SPAIN S.A. 14 41840 PILAS (Sevilla) ACTIVIDADES OLEICOLAS, Autovia Sevilla-Cádiz, Ctra. SPAIN www.acolsa.es S.A. IV Km. 550-600 41703 DOS HERMANAS (Sevilla) AEGEAN STAR FOOD Kral Incir Isletmesi TURKEY www.aegeanstar.com.tr INDUSTRY TRADE LTD. Dallica Mevkii 09800 NAZ AGRICOLA I CAIXA Calle Sindicat, 2 SPAIN www.coopcambrils.com AGRARIA SC CAMBRILS 43850 CAMBRILS SCCL (Tarragona) 2 ENTITÉ/BODY ADRESSE/ADDRESS PAYS/ WEBSITE COUNTRY AGRITALIA S.R.L. -

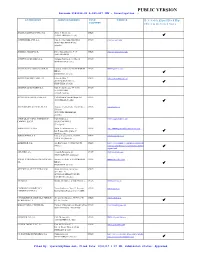

PUBLIC VERSION Barcode:3583338-02 A-469-817 INV - Investigation

PUBLIC VERSION Barcode:3583338-02 A-469-817 INV - Investigation - ENTITÉ/BODY ADRESSE/ADDRESS PAYS/ WEBSITE Believed to Export Black Ripe COUNTRY Olives to the United States ACEITES BORGES PONT, S.A. Avda. J. Trepat s/n SPAIN 25300 TARREGA (Lleida) ACEITES DEL SUR, S.A. Ctra. Sevilla-Cádiz, Km. 550,6 SPAIN www.acesur.com 41700 DOS HERMANAS (Sevilla) ACEITES TOLEDO S.A. Paseo Pintor Rosales, 4 y 6 SPAIN www.aceitestoledo.com 28008 MADRID ACEITUNAS DE MESA S.L. Antiguo Camino de Sevilla s/n SPAIN 41840 PILAS (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS GUADALQUIVIR S.L. Camino Alcoba, s/n 41530 MORON SPAIN www.agolives.com DE LA FRONTERA (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS MONTEGIL, S.L. Eduardo Dato, 9 SPAIN http://www.montegil.es/ 41530 MORON DE LA FRONTERA (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS RUMARIN S.A. Calle Pedro Crespo, 79 41510 SPAIN MAIRENA DEL ALCOR (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS SEVILLANAS S.A. Calle Párroco Vicente Moya, 14 SPAIN 41840 PILAS (Sevilla) ACTIVIDADES OLEICOLAS, S.A. Autovia Sevilla-Cádiz, Ctra. IV Km. SPAIN www.acolsa.es 550-600 41703 DOS HERMANAS (Sevilla) AGRICOLA I CAIXA AGRARIA SC Calle Sindicat, 2 SPAIN www.coopcambrils.com CAMBRILS SCCL 43850 CAMBRILS (Tarragona) AGRO SEVILLA USA Avda. de la Innovación, s/n SPAIN http://www.agrosevilla.com/en/contact/ Ed. Rentasevilla, planta 8ª 41020 Sevilla AGRUCAPERS, S.A. Ctra. de Lorca, Km 3,2 30880 SPAIN www.agrucapers.es AGUILAS (Murcia) ALMINTER, S.A. Av. Río Segura, 9 30562 CEUTI SPAIN http://www.aliminter.com/index.php/produ (Murcia) ctos-nacional/bangor-encurtidos/aceitunas- negras.html AMANIDA SA Avenida Zaragoza, 83 SPAIN www.amanida.com 50630 ALAGON (Zaragoza) ANGEL CAMACHO ALIMENTACION, Avenida del Pilar, 6 41530 MORON SPAIN www.acamacho.com S.L. -

Aloyón (Más Información En Páginas Centrales)

Editorial www.corraldealmaguer.net rranca el número 8 de la revista Aloyón (más información en páginas centrales). con la responsabilidad que nos imprime el En otro orden de cosas, parece ser que finalmen- Ahabernos convertido en la publicación te la Guardia Civil tendrá residencia fija en Corral periódica más duradera de toda la historia de de Almaguer. La preocupación generalizada que su Corral de Almaguer (excluido el programa de las marcha suscitó hace dos años, unida a las críticas fiestas por razones obvias). Esta circunstancia, que de todo tipo y a todos los niveles, han conseguido por un lado nos llena de orgullo, nos obliga por otro finalmente llevar a buen puerto el asunto y los corra- a intentar mejorar cada vez más la información en leños nos podremos sentir de nuevo más seguros ella contenida, conscientes como somos de haber- con su presencia. Desde aquí, nuestra más sincera nos convertido en una fuente de primer orden para felicitación a todos los que han tenido algo que ver el estudio del Corral de Almaguer de comienzos del en su próximo regreso. siglo XXI por las futuras generaciones. Transcurrido ya el segundo aniversario del más Y para comenzar este tercer año de singladura, terrible atentado terrorista de nuestra historia, nada mejor que tirar por tierra ese antiguo mito que hemos echado en falta por parte de nuestras autori- convertía a nuestra localidad en la más insolidaria dades algún breve acto, alguna declaración, algu- de la comarca a la hora de llevar a cabo objetivos na sencilla ofrenda floral que nos hubiera recorda- comunes. -

The Role of Women and Gender in Conflicts

SPANISH MINISTRY OF DEFENCE STRATEGIC DOSSIER 157-B SPANISH INSTITUTE FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES (IEEE) GRANADA UNIVERSITY-ARMY TRAINING AND DOCTRINE COMMAND COMBINED CENTRE (MADOC) THE ROLE OF WOMEN AND GENDER IN CONFLICTS June 2012 GENERAL CATALOGUE OF OFFICIAL PUBLICATIONS http://www.publicacionesoficiales.boe.es Publishes: SECRETARÍA GENERAL TÉCNICA www.bibliotecavirtualdefensa.es © Author and Publisher, 2012 NIPO: 083-12-253-3 (on line edition) NIPO: 083-12-252-8 (e-book edition) Publication date: February 2013 ISBN: 978-84-9781-801-8 (e-book edition) The authors are solely responsible for the opinions expresed in the articles in this publication. The exploitation righits of this work are protected by the Spanish Intellectual Property Act. No parts of this publication may be produced, stored or transmitted in any way nor by any means, electronic, mechanical or print, including photo- copies or any other means without prior, express, written consent of the © copyright holders. SPANISH SPANISH INSTITUTE FOR MINISTRY STRATEGIC STUDIES OF DEFENCE Workgroup number 4/2011 THE ROLE OF WOMEN AND GENDER IN CONFLICTS The ideas contained in this publication are the responsibility of their authors, and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the IEEE, which is sponsoring the publication CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Soledad Becerril Bustamante Chapter I EQUALITY AND GENDER. BASIC CONCEPTS FOR APPLICATION IN THE FIELDS OF SECURITY AND DEFENCE M.ª Concepción Pérez Villalobos Nuria Romo Avilés Chapter II INTEGRATION OF THE PERSPECTIVE OF GENDER INTO THE -

Toledo Comunidad De Castilla-La Mancha

Red Autonómica de Carreteras Toledo Comunidad de Castilla-La Mancha TO 88a TO 220a AFORO TRÁFICO TO 220b CM-5053 2019 N-403 CM-5007 CM-5006 TO 88b CM-530 Iglesuela (La) Almorox TO 88 Paredes de CM-5007 TO 70 TO 11f Escalona Méntrida TO 219 Valmojado TO 202a TO 11 CM-5004 TO 11a CM-543 Casarrubios del Monte Buenaventura TO 416a Almendral de la Cañada Torre de Esteban AP-41 CM-5100 CM-5005 Escalona Hambrán (La) CM-5006 TO 10b Pelahustán CM-41 CM-4004 TO 11e TO 220 Ventas de Carranque Retamosa Ugena TO 90 CM-5001 Nombela TO 68 TO 415a CM-4008 TO 89b Real de San Vicente TO 11d TO 350a A-5 Cedillo del Yeles TO 414a Palomeque Condado A-42 Santa Cruz del Retamar Sotillo de las Palomas Hinojosa Quismondo A-4 TO 67 Illescas Seseña TO 89a de S. Vicente CM-4003 TO 413a TO 65 Castillo Camarena Esquivias Marrupe de Bayuela N-403 Yuncos TO 10 TO 412a CM-43 CM-4010 Cardiel de los Montes CM-4009 TO 89 Cervera de CM-5001 Maqueda Portillo de Toledo R-4 los Montes TO 350 Arcicóllar TO 10a Yuncler CM-5100 Fuensalida TO 16b Novés CM-5150 TO 203 Santa Olalla CM-4011 TO 69b N-502 Pantoja TO 56 CM-5002 CM-5002 Alameda A-5 Camarenilla A-4 Aranjuez Cazalegas CM-4024 Huecas de la Sagra TO 242 Otero TO 30a CM-322 CM-4011 R-4 CM-4002 Añover CM-5102 Velada TALAVERA DE LA REINA AP-41 TO 14b TO 16c TO 66 de Tajo Torrijos TO 241a Santa Cruz de la Zarza CM-4132 TO 66a TO 351 CM-4058 TO 434a TO 214b CM-4015 A-42 TO 1e Noblejas CM-5103 Villamiel de Toledo Villaseca Villarrubia de Santiago TO 14d TO 15b de la Sagra N-400 A-40 TO 86 R-4 TO 185 CM-4006 Olías del Rey N-400 -

EL YACIMIENTO DE LA ESTACIÓN DE LAS DELICIAS (Madrid) Y LA INVESTIGACIÓN DEL PALEOLÍTICO EN EL MANZANARES

EL YACIMIENTO DE LA ESTACIÓN DE LAS DELICIAS (Madrid) Y LA INVESTIGACIÓN DEL PALEOLÍTICO EN EL MANZANARES por M. S ANTONJA A. PÉREZ-GONZÁLEZ y G. VEGA TOSCANO RESUMEN El yacimiento madrileño de las Delicias, excavado por Obermaier y Wernert en 1918, ha sido durante décadas uno de los más notables del conjunto de localidades paleolíticas clásicas del valle del Manzanares. En el presente artículo se hace un repaso crítico de la documentación ofrecida por la antigua excavación, se evalúan historiográficamente las distintas interpretaciones vertidas sobre la industria del yacimiento y se enumeran algunos de los objetivos sobre los que construir un nuevo proyecto de excavación sobre los depósitos aún conservados del mismo. ABSTRACT The archaeological site of Las Delicias (Madrid) excavated by Obermaier and Wernert in 1918, it has been one of the most important classic palaeolithic sites of the Manzanares valley for years. In this paper we offer a critical review of all the data caming from ancient excavation, together with an historiographical evaluation of the different interpretations based on lithic industry of the site, and finally we want to set some objectives looking for a new archaeological research in the Delicias remaining sediments. Palabras claves Paleolítico, valle del Manzanares, Las Delicias, historia de la investigación, tenazas fluviales. Key words Paleolithic, Manzanares valley, Las Delicias, research history, river terraces 1. Museo de Salamanca. [email protected] 2. Departamento de Geodinámica. Universidad Complutense. [email protected] 3. Departamento de Prehistoria. Universidad Complutense. [email protected] SPAL 9 (2000): 525-555 526 M. SANTONJA / A. PÉREZ-GONZÁLEZ / G. -

Registro Vias Pecuarias Provincia Sevilla

COD_VP N O M B R E DE LA V. P. TRAMO PROVINCIA MUNICIPIO ESTADO LEGAL ANCHO LONGITUD PRIORIDAD USO PUBLICO 41001001 CAÑADA REAL DE SEVILLA A GRANADA 41001001_01 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 75 10 3 41001001 CAÑADA REAL DE SEVILLA A GRANADA 41001001_03 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 75 1629 3 41001001 CAÑADA REAL DE SEVILLA A GRANADA 41001001_02 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 75 2121 3 41001002 VEREDA DE OSUNA A ESTEPA 41001002_06 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 21 586 3 41001002 VEREDA DE OSUNA A ESTEPA 41001002_05 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 21 71 3 VEREDA DE SIERRA DE YEGÜAS O DE LA 41001003 PLATA 41001003_02 SEVILLA AGUADULCE CLASIFICADA 21 954 3 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_04 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 224 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_06 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 3244 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_07 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 57 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_08 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 17 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_05 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 734 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_01 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 1263 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_03 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 3021 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_02 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 428 1 DESLINDE 41002001 CAÑADA REAL DE MERINAS 41002001_09 SEVILLA ALANIS INICIADO 7,5 K 75 2807 1 CAÑADA REAL DE CONSTANTINA Y DESLINDE 41002002 CAZALLA 41002002_02 SEVILLA -

Casamiento Y Descendencia

CAPITULO XIII. HISTORIA DE LA FAMILIA TUSET Y LA UNIÓN CON LA FAMILIA TAMAYO. CAPÍTULO XV. !oña "arlota #amayo "ontreras, casamiento y descendencia TAMAYO. RECUERDOS DE UNA FAMILIA 731 732 LUIS JIMÉNEZ-TUSET Y MARTÍN CAPITULO XV. DOÑA CARLOTA TAMAYO CONTRERAS, CASAMIENTO Y DESCENDENCIA. XIV.5.2. Doña Carlota Tamayo Contreras ue la segunda hija del matrimonio de don Manuel Tamayo y Ra- mírez y doña María Josefa de Contreras Montes y Villavicencio. Nació en Osuna en el año de 1866. Y casó en dicha villa con don Antonio de Castro y Arregui. Si nos detenemos a estudiar algunas de las costumbres y métodos de la familia Ta- mayo, podemos comprobar que hasta el nombre de los hijos lo tenían pensado con anterioridad a su nacimiento. Como la natalidad no estaba controlada ni se sabían cuántos hijos podrían tener, ellos ya al primero o a la primera le ponían todos los nombres que en su pensamiento tenían para los demás. Analizando la partida de bautismo de su hermana mayor y mi bisabuela Carmen Tamayo dice así: Se le puso por nombre Carmen, como su abuela paterna (marquesa de la Go- mera) Manuela, como la que posteriormente fue su tercera hermana, Josefa como su madre, Antonia como su posterior y único hermano Antonio Tamayo (mar- ques de la Gomera), Carlota como su segunda hermana y Arcadia y de la Santí- sima Trinidad como era de costumbre al ser San Arcadio el patrón de Osuna, y hasta el de Rafaela como posteriormente fue el de la hija mayor de doña Carlota Tamayo y don Antonio de Castro.