San Bernardino/ Leslie Canyon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona by Ric Windmiller 3

THE COCHISE QUARTERLY Volume 1 Number 2 June, 1971 CONTENTS Early Hunters and Gatherers in Southeastern Arizona by Ric Windmiller 3 From Rocks to Gadgets A History of Cochise County, Arizona by Carl Trischka 16 A Cochise Culture Human Skeleton From Southeastern Arizona by Kenneth R. McWilliams 24 Cover designed by Ray Levra, Cochise College A Publication of the Cochise County Historical and Archaeological Society P. O. Box 207 Pearce, Arizona 85625 2 EARLY HUNTERS AND GATHERERS IN SOUTHEASTERN ARIZONA* By Ric Windmiller Assistant Archaeologist, Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona During the summer, 1970, the Arizona State Museum, in co- operation with the State Highway Department and Cochise County, excavated an ancient pre-pottery archaeological site and remains of a mammoth near Double Adobe, Arizona.. Although highway salvage archaeology has been carried out in the state since 1955, last sum- mer's work on Whitewater Draw, near Double Adobe, represented the first time that either the site of early hunters and gatherers or re- mains of extinct mammoth had been recovered through the salvage program. In addition, excavation of the pre-pottery Cochise culture site on a new highway right-of-way has revealed vital evidence for the reconstruction of prehistoric life-ways in southeastern Arizona, an area that is little known archaeologically, yet which has produced evidence to indicate that it was early one of the most important areas for the development of and a settled way of life in the Southwest. \ Early Big Game Hunters Southeastern Arizona is also important as the area in which the first finds in North America of extinct faunal remains overlying cul- tural evidences of man were scientifically excavated. -

Coronado National Memorial Historical Research Project Research Topics Written by Joseph P. Sánchez, Ph.D. John Howard White

Coronado National Memorial Historical Research Project Research Topics Written by Joseph P. Sánchez, Ph.D. John Howard White, Ph.D. Edited by Angélica Sánchez-Clark, Ph.D. With the assistance of Hector Contreras, David Gómez and Feliza Monta University of New Mexico Graduate Students Spanish Colonial Research Center A Partnership between the University of New Mexico and the National Park Service [Version Date: May 20, 2014] 1 Coronado National Memorial Coronado Expedition Research Topics 1) Research the lasting effects of the expedition in regard to exchanges of cultures, Native American and Spanish. Was the shaping of the American Southwest a direct result of the Coronado Expedition's meetings with natives? The answer to this question is embedded throughout the other topics. However, by 1575, the Spanish Crown declared that the conquest was over and the new policy of pacification would be in force. Still, the next phase that would shape the American Southwest involved settlement, missionization, and expansion for valuable resources such as iron, tin, copper, tar, salt, lumber, etc. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado’s expedition did set the Native American wariness toward the Spanish occupation of areas close to them. Rebellions were the corrective to their displeasure over colonial injustices and institutions as well as the mission system that threatened their beliefs and spiritualism. In the end, a kind of syncretism and symbiosis resulted. Today, given that the Spanish colonial system recognized that the Pueblos and mission Indians had a legal status, land grants issued during that period protects their lands against the new settlement pattern that followed: that of the Anglo-American. -

SPECIES LIST (List Follows the Newest AOU Order)

Southeast Arizona The Nature Conservancy Legacy Club August 11- 18, 2012 SPECIES LIST (List follows the newest AOU order) Black-bellied Whistling-Duck––4 in the wetland near Elgin, whistling as they flew Mexican Duck (Mallard)––at the Elgin wetland and Willcox’s “Lake Cochise” Northern Shoveler––a few lounging at the Willcox ponds Ruddy Duck––one male and a female, paddling behind the reeds at Willcox golf pond Scaled Quail––a few glimpsed near Whitewater Draw, seen well as they crossed the road Gambel’s Quail––small groups seen almost daily Montezuma Quail––heard only, whistling in Huachuca Canyon, what a tease! Pied-billed Grebe––1 at the Willcox golf pond Great Blue Heron––at the Elgin wetland and flying behind Casa de San Pedro Black-crowned Night-Heron––1 immature flushed at the Willcox golf pond White-faced Ibis––2 distant birds at Whitewater and others flying over the Willcox ponds Black Vulture––a single perched on the cliff above Patagonia’s roadside rest, great scope views for all. Turkey Vulture––throughout White-tailed Kite––3 in the Elgin grasslands, what a thrill to see them at dusk, after a very full day Northern Harrier––1 in the Elgin grasslands Cooper’s Hawk––1 near Patagonia-Sonoita Creek Preserve, one very close by as we passed it on the road leaving Tucson Gray Hawk––heard only in several locations in the lowlands. With ample time in two of its favorite haunts, we were surprised not to get “cracking” views. Swainson’s Hawk––fairly common along the roadsides on most days, particularly noticeable near Portal. -

SPRING HILL RANCH Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB No. 1024-0018 SPRING HILL RANCH Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_______________________________ National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Spring Hill Ranch Other Name/Site Number: Deer Park Place; Davis Ranch; Davis-Noland-Merrill Grain Company Ranch; Z Bar Ranch 2. LOCATION Street & Number: North of Strong City on Kansas Highway 177 Not for publication: City/Town: Strong City Vicinity: X State: Kansas County: Chase Code: 017 Zip Code: 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): __ Public-Local: __ District: X Public-State: __ Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 8 _1_ buildings __ sites _5_ structures _ objects 14 12 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 2 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing :N/A Designated a NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK on NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB No 1024-0018 SPRING HILL RANCH Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Eyec Sail Dzan

Desert Plants, Volume 6, Number 3 (1984) Item Type Article Authors Hendrickson, Dean A.; Minckley, W. L. Publisher University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Desert Plants Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 27/09/2021 19:02:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/552226 Desert Volume 6. Number 3. 1984. (Issued early 1985) Published by The University of Arizona at the Plants Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum eyec sail Dzan Ciénegas Vanishing Climax Communities of the American Southwest Dean A. Hendrickson and W. L. Minckley O'Donnell Ciénega in Arizona's upper San Pedro basin, now in the Canelo Hills Ciénega Preserve of the Nature Conservancy. Ciénegas of the American Southwest have all but vanished due to environmental changes brought about by man. Being well- watered sites surrounded by dry lands variously classified as "desert," "arid," or "semi- arid," they were of extreme importance to pre- historic and modern Homo sapiens, animals and plants of the Desert Southwest. Photograph by Fritz jandrey. 130 Desert Plants 6(3) 1984 (issued early 1985) Desert Plants Volume 6. Number 3. (Issued early 1985) Published by The University of Arizona A quarterly journal devoted to broadening knowledge of plants indigenous or adaptable to arid and sub -arid regions, P.O. Box AB, Superior, Arizona 85273 to studying the growth thereof and to encouraging an appre- ciation of these as valued components of the landscape. The Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum at Superior, Arizona, is sponsored by The Arizona State Parks Board, The Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum, Inc., and The University of Arizona Frank S. -

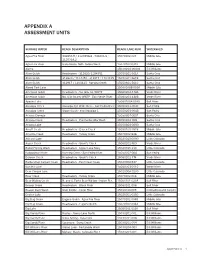

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Bird List of San Bernardino Ranch in Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico

Bird List of San Bernardino Ranch in Agua Prieta, Sonora, Mexico Melinda Cárdenas-García and Mónica C. Olguín-Villa Universidad de Sonora, Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico Abstract—Interest and investigation of birds has been increasing over the last decades due to the loss of their habitats, and declination and fragmentation of their populations. San Bernardino Ranch is located in the desert grassland region of northeastern Sonora, México. Over the last decade, restoration efforts have tried to address the effects of long deteriorating economic activities, like agriculture and livestock, that used to take place there. The generation of annual lists of the wildlife (flora and fauna) will be important information as we monitor the progress of restoration of this area. As part of our professional training, during the summer and winter (2011-2012) a taxonomic list of bird species of the ranch was made. During this season, a total of 85 species and 65 genera, distributed over 30 families were found. We found that five species are on a risk category in NOM-059-ECOL-2010 and 76 species are included in the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It will be important to continue this type of study in places that are at- tempting restoration and conservation techniques. We have observed a huge change, because of restoration activities, in the lands in the San Bernardino Ranch. Introduction migratory (Villaseñor-Gómez et al., 2010). Twenty-eight of those species are considered at risk on a global scale, and are included in Birds represent one of the most remarkable elements of our en- the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature vironment, because they’re easy to observe and it’s possible to find (IUCN). -

Environmental Assessment

San Bernardino and Leslie Canyon National Wildlife Refuges Comprehensive Management Plan 1995 - 2015 Environmental Assessment U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 2 Albuquerque, New Mexico U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE ENVIRONMENTAL ACTION MEMORANDUM Within the spirit and intent of the Council on Environmental Quality's regulations for implementing the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and other statutes, orders, and policies that protect fish and wildlife resources, I have established the following administrative record and have determined that the action of: Implementation of a programmatic Comprehensive Management Plan for the San Bernardino and Leslie Canyon National Wildlife Refuges is a categorical exclusion as provided by 516 DM 6, Appendix 1, Section B(4). No further documentation will be made. is found not to have significant environmental effects as determined by the attached Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact. X is found to have special environmental conditions as described in the attached Environmental Assessment. The attached Finding of No Significant Impact will not be fmal nor any actions taken pending a 30-day period for public review (40 CFR 1501.4(e)(2)). is found to have significant effects, and therefore a "Notice of Intent" will be published in the Federal Register to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement before the project is considered further. is denied because of environmental damage, Service policy, or mandate. is an emergency situation. Only those actions necessary to control the immediate impacts of the emergency will be taken. Other related actions remain subject to NEPA review. Other supporting documents: Finding of No Significant Impact, Environmental Assessment for San Bernardino and Leslie Canyon National Wildlife Refuges Comprehensive Management Plan. -

Ca-Lower-Colorado-River-Valley-Pkwy

I • I I I ) I I A REPORT TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES ---1 I 'I I I I THE LOWER I COLORADO I RIVER I VALLEY • PARKWAY I I D- '°'le> F; 1-e. ·• NFS- ' f\CAc:.+... \ V"C. , ~ P,of>oseol I ~~~~=-'~c f~l~~c~~w I THE LOWER COLORADO I filVERVALLEYPARKWAY I I I A proposal for a National Parkway and Scenic Recreation Road System along the Lower Colorado River Valley in 'I California, Arizona, and Nevada. I NATIONAL PARK .i DENVER SEfiViC I ·-.-:. a.t ..1flkllb""ll.--';,.i. n II"~ r.· " •· \..' ;: · I ;:~::::.;.;:;.:J I I I U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service I in cooperation with Lower Colorado River Office Bureau of Land Management • PLE~\SE RtTUR?j TO: I February 1969 I , lJnited States Department of the Interior OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY I WASHINGTON, D.C. 20240 I I Dear Mr. President: We are pleased to transmit herewith. a report on the feasibility anc;l desirability of developing a nation~l p;;i.rkwa,y and sc;enic recreation I road system within. the Lower C9l9rado River· Vaiiey in Arizona, Califo~nia, and Nevada, from the Lake Mead National Recreation I Area and Davis Dam on the north to the International Boup.d:;i.ry ~ith Mexico on the south in: the vicinity of San Luis, Arizqna arid Mexic.o.· . ·. ' .. ·.' . ·. I This :i;eport is based on ci. study 11,'lade by the Lower Col<;>rado River Office ap.d the NatiQnal :Par~ Service pf this Depa.rtmep.t with engineerin.g assistance by the Buqlau of Public Roads of the Departmep.t of . -

Cross Border Fish and Wildlife Recovery and Habitat Restoration in the San Bernardino Valley Valer Austin and Sadie Hadley

PART THR ee . STAK E HOLD E RS : CAS E S AND PE RS pe CTIV E S Cross Border Fish and Wildlife Recovery and Habitat Restoration in the San Bernardino Valley ValeR AUSTIN anD SADIE HaDleY Cooperation efforts are currently underway gion in the San Bernardino Valley, reflecting the impor- between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service tance of landowners’ participation in their effectiveness. (USFWS) and land owners on either side of It highlights the main achievements of the programs and U.S.-Mexico border who are promoting activ- explains how construction of the border barrier under- ities that will guarantee the perpetuation of mines the efforts and success achieved to date through habitat and water sources, promote scientific this means of cooperation. research and introduce populations of native The geographical region of the San Bernardino Valley fish and wildlife species into this broad region. comprises the four corners of the states of Arizona, New The results of these recovery actions, how- Mexico, Sonora and Chihuahua and is renowned for its ever, are being threatened by the U.S. Depart- enormous biological richeness on either side of the bor- ment of Homeland Security (DHS). der line. The San Bernardino Marsh has historically been This chapter describes the actions carried out regard- the largest wetland in the region and forms a valuable ing wildlife conservation and restoration in the border re- wildlife corridor between the Sierra Madre Occidental in Brownsville, U.S. Photo: Wendy Shattil 29 ila Monster, Cuenca Los Ojos. Photo: Krista Schlyer G Mexico and the Rocky Mountains in the north. -

ANNUAL T Tor Bertha V1nnond Deoember 1, 1936

Annual Report of Home Demonstration Agent, Cochise County 1937 Item Type text; Report Authors University of Arizona. Agricultural Extension Service. Home Demonstration Agents; Virmond, Bertha J. Publisher University of Arizona Rights Public Domain: This material has been identified as being free of known restrictions under U.S. copyright law, including all related and neighboring rights. Download date 02/10/2021 06:58:03 Item License http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/637478 ANNUAL .N A R RAT I V ERE p' 0 R T tor cocarss C OCNTY Bertha V1nnond C.cunty Home Demonstration Agent Deoember 1, 1936 to Deoember 1, 193'7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page status of County Organization • · · • • • • • · 1 Program of Work. • · · · • • • • • 2 Homemakers Club s · • • • · • • • • • • • 3-4-5 Nutrition. • • • • · · · · · • · • 6 8c 23 Food Preparation • · • • • · • • .. 6 8c 23 Adult Work • · • · · • 6 4-H Baking Clubs • · · 23 4-H Meal Planning Club. • · . 26 Food Preservation • 7 8c 28 Adult . • · 7 4-H Canning Clubs · · · 28 . 9 Clothing • & 31 Adult Work. • • · · 9 4-H Garment Making Clubs. • · . 31 11 8c 45 Home Management • • 11 Adult Work. • • · • 45 4-H Home Management Club · 13 &. 48 Home FUrnishings . • · · · · • 13 Adult Work • • · · · · 48 4-H Handicraft Clubs • • . Health & . Home, Sanitation. 56 4-H Health Clubs · . 56 Miscellaneous • . 16 Adult Work . · . 16 w. P. A. Work . 16 Fairs • . · . · . 16 Organization · . 17 Club Houses . 17 Magazines • . · . · . 18 News Writing . 18 stewart Garden Club • · . 18 Willcox Woman's Club . 19 Cochise County History · . 19 Annual Leave • • . 20 4-H Club History •• · . 21 4-H Music Appreciation • · . -

National Wildlife Refuge Management on the United States/Mexico Border

National Wildlife Refuge Management on the United States/Mexico Border William R. Radke U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; San Bernardino and Leslie Canyon National Wildlife Refuges, Douglas, Arizona Abstract—Many conservation strategies have been developed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in co- operation with others to protect habitat and enhance the recovery of fish and wildlife populations in the San Bernardino Valley, which straddles Arizona, United States, and Sonora, Mexico. Habitats along this international border have been impacted by illegal activities, frustrating recovery of rare species. In addition, potential threats to national security have prompted the United States to aggressively control the country’s boundaries, thus creating additional challenges for land managers mandated with protecting the nation’s landscapes, natural resources, and associated values. Such challenges are not insurmountable and, with focused coordination, resource management and border security can be achieved and can often compliment one another. With or without the influence of changes along the international border, an effective species recovery strategy must include a coordinated approach that involves assessing the biological requirements of selected species through combinations of inventory, monitoring, and research activities; managing and protecting existing and historic habitats and populations; assessing potential reintroductions of key species into appropriate habitats where feasible; managing exotic plants and animals that threaten the recovery of desired conditions; and providing outreach and education relative to the species, their habitats, and the ecosystems upon which all fish, wildlife, and humans depend. Introduction and Management Context Service and environmentally sensitive landowners in the United States and in Mexico are implementing conservation strategies to protect The U.S.