Australia's Pacific Pivot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter: Quarter 1, 2021

2021 TRANS-FORMTrans Pacific Union Newsletter 01, Jan-Mar Be a Transformer! On Easter weekend, I was sharing devotions for the youth camp that was held at Navesau Adventist High School in Fiji. What I saw really inspired me. These young people were not there just to have a good time, however were there to transform Navesau. They planted thousands of root crops, vegetables, painted railings and cleaned up the place. At the end of the camp, they donated many things for the school – from equipment for the computer lab, cooking utensils, fencing wire and even family household items. I am sure that it amounted to worth thousands of dollars. I literally saw our Vision Statement come alive. I saw ‘A Vibrant Adventist youth movement, living their hope in Jesus and transforming Navesau’. I know that there were many youth camps around the TPUM who also did similar things and I praise the Lord for the commitment our people have made to transform our Pacific. We can work together to transform our communities, and we can also do it individually. Jesus Christ illustrates this with this Parable in Matthew 13:33: “The kingdom of heaven is like yeast…mixed into…flour until it is worked all through the dough.” Jesus invites us to imagine the amazing properties of a little bit of yeast; it can make dough rise so that it bakes into wonderful bread. Like yeast, only a small expression of the kingdom of Jesus Christ in our lives can make an incredible impact on the lives and culture of people around us. -

Vanuatu Mission, Nambatu, Vila, Vanuatu

Vanuatu Mission, Nambatu, Vila, Vanuatu. Photo courtesy of Nos Terry. Vanuatu Mission BARRY OLIVER Barry Oliver, Ph.D., retired in 2015 as president of the South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists, Sydney, Australia. An Australian by birth Oliver has served the Church as a pastor, evangelist, college teacher, and administrator. In retirement, he is a conjoint associate professor at Avondale College of Higher Education. He has authored over 106 significant publications and 192 magazine articles. He is married to Julie with three adult sons and three grandchildren. The Vanuatu Mission is a growing mission in the territory of the Trans-Pacific Union Mission of the South Pacific Division. Its headquarters are in Port Vila, Vanuatu. Before independence the mission was known as the New Hebrides Mission. The Territory and Statistics of the Vanuatu Mission The territory of the Vanuatu Mission is “Vanuatu.”1 It is a part of, and reports to the Trans Pacific Union Mission which is based in Tamavua, Suva, Fiji Islands. The Trans Pacific Union comprises the Seventh-day Adventist Church entities in the countries of American Samoa, Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Niue, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu. The administrative office of the Vanuatu Mission is located on Maine Street, Nambatu, Vila, Vanuatu. The postal address is P.O. Box 85, Vila Vanuatu.2 Its real and intellectual property is held in trust by the Seventh-day Adventist Church (Vanuatu) Limited, an incorporated entity based at the headquarters office of the Vanuatu Mission Vila, Vanuatu. The mission operates under General Conference and South Pacific Division (SPD) operating policies. -

2Nd Quarter 2016

MissionCHILDREN’S 2016 • QUARTER 2 • SOUTH PACIFIC DIVISION www.AdventistMission.org Contents On the Cover: Eleven-year-old Ngatia started a children’s Sabbath School under the trees. When the group couldn’t meet there anymore, God provided a very unusual meeting place. COOK ISLANDS FIJI 4 Life on the Island/ April 2 22 The Mystery of the Matches | June 4 24 Praying for Parents | June 11 SOLOMON ISLANDS 6 The Snooker Hut Girl| April 9 NEW ZEALAND 8 Giving the Invitation, Part 1 | April 16 26 Working With Jesus | June 18 10 Giving the Invitation, Part 2 | April 23 RESOURCES 12 The Children of Ngalitatae | April 30 28 Thirteenth Sabbath Program | June 25 PAPUA NEW GUINEA 30 Future Thirteenth Sabbath Projects 14 The Early Bird | May 7 31 Flags 16 Helping People | May 14 32 Recipes and Activities 18 Angels Are Real! | May 21 35 Resources/Masthead 20 The Unexpected Church | May 29 36 Map Your Offerings at Work The first quarter 2013, Thirteenth Sabbath Offering helped to build three Isolated Medical Outpost clinics in some of the most remote areas of Papua New Guiena, Vanuatu, and the Solomon Islands. These clinics provide the only easily accessible medical service to thousands of people living in these areas and offer a Seventh- day Adventist presence into these previously unentered areas. Thank you for your generosity! Above: The Buhalu Medical Clinic and staff house in Papua New Guiena were made possible in part through the Thirteenth Sabbath Offering. South Pacific Division ISSION ©2016 General Conference of M Seventh-day Adventists®• All rights reserved 12501 Old Columbia Pike, DVENTIST Silver Spring, MD 20904-6601 A 800.648.5824 • www.AdventistMission.org 2 Dear Sabbath School Leader, This quarter features the South Pacific and seashells. -

Votes & Proceedings

Votes & Proceedings Of the Sixteenth Parliament No. 35 First Sitting of the Twenty-eighth Meeting 10.00 a.m. Friday, 22nd December 2006 1. The House met on Friday, 22nd December 2006 at 10 a.m. in accordance with the resolution made by the House on Thursday, 9th November 2006. 2. The Hon. Valdon K. Dowiyogo, M.P., Speaker of Parliament, took the Chair and read Prayers. 3. Statements from the Chair (i) ‘Members of the House, before we proceed with our normal business of the day, I have four statements to be made to this august House. As Members might be aware that the Parliament of Nauru has been provided with two Toyota Prado diesel four-wheel vehicles as a grant by the Government of India. These vehicles will serve the long term use of the Parliament in smoothening its work and facilitating the Members in their official duties. This project was taken by me with the then Minister for External Affairs who is also the Prime Minister of India and I am happy that they have acceded to my request. I have also regulated the use of the vehicle within the Parliament Secretariat in order to achieve the highest levels of efficiency and diligence. I would also like to state in no uncertain terms that this assistance would not have come without the endeavours of our Department of Foreign Affairs who had over the years strengthened the bilateral ties with India and the Minister, Hon. David Adeang, who talked to the Deputy Minister of External Affairs, Government of India, Hon. -

The Dynamic Gravity Dataset: Technical Documentation Update

The Dynamic Gravity Dataset: Technical Documentation Update Note Version 2.00 Abstract This document provides an update to the technical documentation for the Dynamic Gravity dataset, describing changes from Version 1.00 to Version 2.00. For full descrip- tion of the contents and construction of the dataset, see full technical documentation for Version 1.00 on the dataset page at https://www.usitc.gov/data/gravity/dgd.htm. This documentation is the result of ongoing professional research of USITC Staff and is solely meant to represent the opinions and professional research of individual authors. It is not meant to represent in any way the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission or any of its individual Commissioners. It is circulated to promote the active exchange of ideas between USITC Staff and recognized experts outside the USITC, professional development of Office Staff and increase data transparency by encouraging outside professional critique of staff research. Please address all correspondence to [email protected]. 1 1 Introduction The Dynamic Gravity dataset contains a collection of variables describing aspects of countries and territories as well as the ways in which they relate to one-another. Each record in the dataset is defined by a pair of countries or territories and a year. The records themselves are composed of three basic types of variables: identifiers, unilateral character- istics, and bilateral characteristics. The updated dataset spans the years 1948{2019 and reflects the dynamic nature of the globe by following the ways in which countries have changed during that period. The resulting dataset covers 285 countries and territories, some of which exist in the dataset for only a subset of covered years.1 1.1 Contents of the Documentation The updated note begins with a description of main changes to the dataset from Version 1.00 to Version 2.00 in section 1.2 and a table of variables available in Version 1.00 and Version 2.00 of the dataset in section 1.3. -

History of the Pacific Islands Studies Program at the University of Hawaii: 1950-198

HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES PROGRAM AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII: 1950-198 by AGNES QUIGG Workinq Paper Series Pacific Islands Studies Program canters for Asian cmd Pacific Studies University of Hawaii at Manoa EDITOR'S OOTE The Pacific Islands Studies Program. often referred to as PIP, at the University of Hawaii had its beginnings in 1950. These were pre-statehood days. The university was still a small territorial institution (statehood came in 1959), and it is an understatement to say that the program had very humble origins. Subsequently, it has had a very checkered history and has gone through several distinct phases. These and the program's overall history are clearly described and well analyzed by Ms. Agnes Quigg. This working paper was originally submitted by Ms. Quigg as her M.A. thesis in Pacific Islands Studies. Ms. Quigg' is a librarian in the serials division. Hamnlton Library, University of Hawaii. Earlier in this decade, she played a crucial role in the organization of the microfilming of the archives of the U.S. Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, Office of the High CommiSSioner, Saipan, Northern Marianas. The archives are now on file at Hamilton Library. Formerly, Ms. Quigg was a librarian for the Kamehameha Schools in Honolulu. R. C. Kiste Director Center for Pacific Islands Studies THE HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES PROGRAM AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII: 1950-1986 By Agnes Quigg 1987 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to a number of people who have helped me to complete my story. Judith Hamnett aided immeasurably in my knowledge of the early years of PIP, when she graciously turned over her work covering PIP's first decade. -

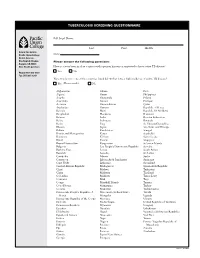

Tuberculosis Screening Questionnaire

TUBERCULOSIS SCREENING QUESTIONNAIRE Full Legal Name: Last First Middle Return this form to: Pacific Union College Date: Health Services One Angwin Avenue Please answer the following questions: Angwin, CA 94508 Attn: Health Services Have you ever been in close contact with a person known or suspected to have active TB disease? Yes No Phone (707) 965-6339 Fax (707) 965-6243 Were you born in one of the countries listed below that have a high incidence of active TB disease? Yes (Please circle) No Afghanistan Ghana Peru Algeria Guam Philippines Angola Guatemala Poland Argentina Guinea Portugal Armenia Guinea-Bissau Qatar Azerbaijan Guyana Republic of Korea Bahrain Haiti Republic Of Moldova Bangladesh Honduras Romania Belarus India Russian Federation Belize Indonesia Rwanda Benin Iraq St. Vincent/Grenadines Bhutan Japan Sao Tome and Principe Bolivia Kazakhstan Senegal Bosnia and Herzegovina Kenya Seychelles Botswana Kiribati Sierra Leone Brazil Kuwait Singapore Brunei Darussalam Kyrgyzstan Solomon Islands Bulgaria Lao People’s Democratic Republic Somalia Burkina Faso Latvia South Africa Burundi Lesotho Sri Lanka Cambodia Liberia Sudan Cameroon Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Suriname Cape Verde Lithuania Swaziland Central African Republic Madagascar Syrian Arab Republic Chad Malawi Tajikistan China Malaysia Thailand Colombia Maldives Timor-Leste Comoros Mali Togo Congo Marshall Islands Tunisia Cote d’Ivoire Mauritania Turkey Croatia Mauritius Turkmenistan Democratic People’s Republic of Micronesia (Federal State) Tuvalu Korea Mongolia Uganda Democratic -

Pacific Food Summit

Pacific Food Summit 21-23 April2010 Port Vila, Vanuatu (at~~l World Health ~~§ Organization --"?~ -=--- Western Pacific Region FOOD SECURE PACIFIC REPORT FJFIC FOOD SUMMIT Port Vila, Vanuatu 21-23 April 2010 WHO/WPRO LmRARY MANILA. PHILIPPINES 3 0 SEP 2011 Manila, Philippines December 2010 WPDHP1002530-E Report Series Number: RS/2010/GE/22(V AN) REPORT PACIFIC FOOD SUMMIT Convened by: WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION REGIONAL OFFICE FOR THE WESTERN PACIFIC In collaboration with: FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS GLOBAL HEALTH INSTITUTE PACIFIC ISLAND FORUM SECRETARIAT SECRETARIAT OF THE PACIFIC COMMUNITY UNITED NATIONS CHILDREN'S FUND Port Vila, Vanuatu 21-23 April 2010 Not for sale Printed and distributed by: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific Manila, Philippines December 2010 NOTE The views expressed in this report are those of the participants of the Pacific Food Summit and do not necessarily reflect policies of the Organization. This report has been prepared by the World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific for governments of Member States in the Region and for those who participated in the Pacific Food Summit, which was held in Port Vila, Vanuatu from 21 to 24 April2010. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........ ... .... .... ........ .......... ...... ..... ... ... ... ... ...... ....... 1 1.1 Objectives ................ ..... ........ .. ... .. .. ..... ........ .... .... ..................... ... 2 1.2 Opening Remarks ........ ... .... ... ...... ...... .............. -

'Pooled Regional Governance' in the Island Pacific? Lessons from History

PACIFIC ECONOMIC BULLETIN Feature PACIFIC INTEGRATION AND REGIONAL GOVERNANCE ‘Pooled regional governance’ in the island Pacific? Lessons from history Greg Fry Director of Graduate Studies in International Affairs, Department of International Relations, The Australian National University Since mid 2003 the Australian Government Australian push as too heavy handed. The has been attempting to reshape and revitalise Forum agreed not only to action on the regional cooperation in the South Pacific particular cases the Prime Minister had around the concept of ‘pooled regional raised, that of a regional police training unit governance’. The notion was first promoted and an Australian-sponsored study of civil by Prime Minister John Howard in the aviation, but also to a major overhaul of context of announcing his government’s regional arrangements under the auspices intention to lead a regional assistance of the Forum. In some senses the resultant mission to Solomon Islands.1 The Prime Pacific Plan became the embodiment of a Minister argued that the smaller Pacific states broader notion of ‘pooled regional needed to share resources if they were to governance’, not just the sharing of resources overcome the constraints imposed by their and saving of costs in particular sectors but small size and lack of capacity. He illustrated a commitment to a ratcheting-up of the the point by referring to the absurdity of each cooperative effort as implied in the term island country trying to run its own airline ‘regional governance’ as against ‘regional or train its police when these could be done cooperation’ (Eminent Persons’ Group 2004). through a pooling of resources. -

Western Pacific Union Mission, Honiara, Solomon Islands

Headquarters office of the Western Pacific Union Mission, Honiara, Solomon Islands. Photo courtesy of Silent Tovosia. Western Pacific Union Mission BARRY OLIVER Barry Oliver, Ph.D., retired in 2015 as president of the South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists, Sydney, Australia. An Australian by birth Oliver has served the Church as a pastor, evangelist, college teacher, and administrator. In retirement, he is a conjoint associate professor at Avondale College of Higher Education. He has authored over 106 significant publications and 192 magazine articles. He is married to Julie with three adult sons and three grandchildren. The Western Pacific Union Mission (WPUM) existed between 1972 and 2000. It was a constituent union of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists and was part of the South Pacific Division of the General Conference (SPD). Its headquarters when dissolved were in Honiara, Solomon Islands.1 The Territory and Statistics of the Western Pacific Union Mission The territory of the Western Pacific Union Mission was “Kiribati, Nauru, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu; comprising the Eastern Solomon Islands, Kiribati, Malaita, Vanuatu, and Western Solomon Islands Missions.”2 The administrative office of the Western Pacific Union Mission was at Palm Drive, Lunga, Honiara, Solomon Islands, on the southern outskirts of the nation’s capital. The postal address was P.O. Box R145, Ranandi, Honiara, Solomon Islands.3 In the 2000 Annual Statistical Report of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, the Western Pacific Union Mission was listed as having 231 organized churches and 368 companies. Church membership at the end of 1999 was 45,950. The union had 852 active employees. -

New Zealand Pacific Union Conference, South Pacific Division

The New Zealand Pacific Union Conference administrative headquarters in Auckland, New Zealand. Photo courtesy of Maheata Adeline. New Zealand Pacific Union Conference, South Pacific Division BARRY OLIVER Barry Oliver, Ph.D., retired in 2015 as president of the South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists, Sydney, Australia. An Australian by birth Oliver has served the Church as a pastor, evangelist, college teacher, and administrator. In retirement, he is a conjoint associate professor at Avondale College of Higher Education. He has authored over 106 significant publications and 192 magazine articles. He is married to Julie with three adult sons and three grandchildren. The New Zealand Pacific Union Conference is a constituent union of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists and is one of four unions in the South Pacific Division of the General Conference.1 Current Territory and Statistics The territory of the New Zealand Pacific Union Conference (NZPUC) is “Cook Islands, French Polynesia, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Pitcairn Island, and Wallis and Futuna Islands; comprising the North New Zealand, and South New Zealand Conferences; the Cook Islands, French Polynesia, and New Caledonia Missions; and the Pitcairn Island Field Station.”2 The NZPUC headquarters is located at 18 Fencible Drive, Howick, Auckland, New Zealand. The postal address is Private Bag 94200, Howick, Auckland, 2145, New Zealand. The unincorporated activities of the NZPUC are governed by a constitution that is based on the model union conference constitution -

Sovereignty As Currency for Oceania's Island States Lizzie Yarina

PEER REVIEW Micro- state- craft: Sovereignty as Currency for Oceania’s Island States Lizzie Yarina KEYWORDS Pacific Islands, Oceania, Sovereignty, Statecraft, Microstates Islas del Pacífico, Oceania, soberanía, política, micro-estados Yarina, Lizzie. 2019. “Microstatecraft: Sovereignty as Currency for Oceania’s Island States.” informa 12: 216–231. informa Issue #12 ‘Site Conditions’ 217 SOVEREIGNTY AS CURRENCY FOR OCEANIA’S ISLAND STATES Lizzie Yarina ABSTRACT population and dry ground. The smallest, Nauru, has only 10,000 people inhabiting a single 10- The sovereign archipelagos of the Pacific represent square kilometer island, much of which is no longer the distinctive typology of the ‘microstate.’ Emerging inhabitable as the result of phosphate mining. The in the global post-colonial era, they are many of combined surface area of these island microstates the smallest countries in the world in terms of both is similar to that of Rhode Island, as is the sum of population and land area. Still, as independent their 11 gross domestic products, or GDPs. Still, as states, each has earned a seat in the United Nations independent countries, each maintains a seat in the General Assembly, and other trappings of transna- United Nations General Assembly and all of the other tionally recognized sovereignty. This essay explores trappings of transnationally recognized sovereignty. the microstatecraft of Pacific Island nations—dis- This article explores the currency of sovereignty for tinct transnational negotiations made possible, Pacific microstates, and examines potential risks and desirable, or necessary by the unique characteristics opportunities associated with this ‘microstatecraft.’ of these small island, big ocean states. In particular, microstatecraft refers to the opportunities created In her book Extrastatecraft: the Power of Infrastruc- for these countries by leveraging their very status ture Space, architectural and urban theorist Keller as states.