“Caste” in Kerala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malayalam Syllabus 2020-21Onwards

ST.PHILOMENA’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS), MYSURU (AFFILIATED TO UNIVERSITY OF MYSORE) REACCREDITED BY NAAC WITH B++ GRADE UNDER GRADUATE COURSE – SEMESTER SCHEME Academic year 2020-21 onwards DEPARTMENT OF MALAYALAM St. Philomena’s College (Autonomous), Mysore. Malayalam Syllabus under -2020-21 onwards Page 1 ST. PHILOMENA’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS), MYSURU- 570015 Subject: Malayalam Syllabus for B.A/BBA/BCA/B.SC/BSW/B.COM Course under Semester Scheme. DURATION: TWO YEARS - FOUR SEMESTERS The Scheme of Teaching & Examination From the Academic Year – 2020-2021 Onwards Teaching & Examination Scheme Credit Scheme Title of the Paper TheorHours per Week Max. Marks Credits Duration in Semester y Hours Theory I A Total I Poetry, Prose and Precis writing 04 04 03 70 30 100 II Poetry, Drama and Translation 04 04 03 70 30 100 III Poetry ,Short stories and Letter 04 04 03 70 30 100 writing IV Poetry, Novel and General Essay 04 04 03 70 30 100 St. Philomena’s College (Autonomous), Mysore. Malayalam Syllabus under -2020-21 onwards Page 2 ST. PHILOMENA’S COLLEGE (Autonomous), MYSURU-570 015 Subject: Malayalam REVISED SYLLABUS FOR B.A, B.Sc, B S W, B.Com, B.B.M and BCA UNDER SEMESTER SCHEME From The Academic Year2020-21 Onwards Department of Malayalam Revised the syllabus for the Degree course in the academic year 2016- 17. This is the Second Language syllabus for B.A/B.Sc/B.Com/BBM/BCA & BSW Courses. This syllabus consists of Poetry, Prose and functional language. Poetry section includes poetry from different poets, representing old, medieval and modern age. -

300 BOOKS-Sheet1.Pdf

KARTHAVINTE NAMATHIL ATTUPOKATHA ORMAKAL DAIVATHINTE CHAARANMAAR ANDHAR BADHIRAR MOOKAR KHASAAKKINTE ITHIHASAM ORU POLICE SURGEONTE ORMAKKURIPPUKAL AALCHEMIST KAPALAM NIREESWARAN MAYYAZHIPPUZHAYUDE THEERANGALIL AATUJEEVITHAM AGNICHIRAKUKAL RUTHINTE LOKAM SUGANDHI ENNA ANDAL DEVANAYAKI MULLAPPOONIRAMULLA PAKALUKAL ORU SANKEERTHANAM POLE ORU KUTAYUM KUNHUPENGALUM AARACHAAR VIRALATTAM NEERMATHALAM POOTHAKALAM RICH DAD POOR DAD SOORYANE ANINJA ORU STHREE FRAANCIS ITTYKKORA RAMANEEYAM EE JEEVITHAM RANDAMOOZHAM DANTHASIMHASANAM KERALACHARITHRAM BIRIYANI MARAKKATHIRIKKAN BUDDHIYULLAVARAKAN PATHUMMAYUDE ADU MANJAVEYIL MARANANGAL ENTE KATHA PACHAKUTHIRA (2020 JANUARY) ORU DESATHINTE KATHA BALYAKALASAKHI ORU THERUVINTE KATHA NINGALUTE UPABODHAMANASINTE SAKTHI MANJU RANDITANGAZHI ARDHANAREESWARAN PACHAKUTHIRA (2020 FEBRUARY) 9/8/2020 1 MANUSHYANU ORU AAMUKHAM ENGLISH ENGLISH MALAYALAM DICTIONARY(DC) JANMANTHARA YATHRAKAL MEESA PRATHI POOVANKOZHI INI NJAN URANGATTE PACHAKUTHIRA (2020 MARCH) M T YUDE KATHAKAL LOKATHE NADUKKIYA KOLAPATHAKANGAL ATHIRUKALILLATHA LOKAM NTUPPUPPAKKORANENDARNNU ! KILIMANJARO BOOK STALL MARQUEZ ILLATHA MACCONDO VYATHYASTHARAAKAAN MATHILUKAL NAALUKETTU CHIDAMBARASMARANA KATHAKAL (Unni R) KATHUSOOTHRAM ENTE POLICE JEEVITHAM MAHABHARATHAM SAMSKARIKACHARITHRAM (HB) TWINKLE ROSSAYUM PANTHRANDU KAMUKANMARUM AGNISAAKSHI JEEVITHAM KOCHU KOCHU SANTHOSHANGAL BUDHINI (PB) INDIACHARITHRAM (PART 1 & 2 COMPILED) RAHASYAM UMMACHU YAKSHI PREMALEKHANAM (New Format) EE NIMISHATHIL JEEVIKKU PUTTU 365 KUNHU KATHAKAL APARA ORMASAKTHI NEDAM PARISEELIKKAM` -

April 2019 Sl.No

New books added in April 2019 Sl.No. Call No. Author Title The validity of anumana (inference) in nyaya 1 R PSN 181.43 BAB/V Babu C D system/ 2 R PE 823.007 TAN/R Tania Mary Vivera Reading minds: Impact of smrti tadition 3 R PSS 294.592 6 SMI/I Smitha K on Kerala ethos/ 4 M301 SIV/T Sivaraman Cheriyanad Theranjedutha kathakal/ 5 M 080 VEN/A Venugopal K M Abhimukhangal/ Kuttippuzha Krishan Pillai Vicharaviplavathinte 6 M 894.812 092 JOS/K Joseph Panakkal Deepasikha/ Keraleeya Navothanavum Vagbhatanandagurudeva 7 M 294.561 ABO/K Aboobakkar Kathiyalam num/ Poykayil Appachan Keezhalarute 8 M 303.484 092 LEN/P Lenin K M Vimochakan/ Delhousi square muthal 9 M301 VIJ/D Vijayan P N aandippatti vare/ Achuthanunni Bharatheeya sahitya 10 M 801.95 ACH/B Chathanath darsanam/ 11 M3 MAT/T Mathew K P Theekkattiloote/ Chitrasalabhagalude 12 M301 THO/C Thomas Joseph kappal/ 13 M301 (ITr.) RAB/T Rabindranath Tagore Tagore kathakal/ 14 M301 RAV/K Ravivarma p Kimakurvatha Sanjayana/ 15 M 791.437 MAD/N Madhu Ervavankara Nishadam/ 16 M2 SAY/A Sayed Ponkunnam Aathmanivedanam/ 17 M2 VAS/U Vasudevan Pillai Utampady/ Ere Dweshavum Alpam 18 M2 GNC/E G.N. Cheruvadu Snehavum/ 19 M2 SAN/A G.N. Cheruvadu Abhayarthikal/ 20 M2 JOH/K John Fernandaz Kollakolli/ Gurudeth Cinemayum 21 M 791.430 92 SEN/G Senan N C Jeevithavum/ 22 M301 KAS/O Kasthuri Joseph Autograph/ Aswathamavinte 23 M301 RAM/A Ramesh Babu theeram/ 24 M301 SAJ/O Sajiv Kumar S Outsider/ 25 M301 VEN/A Venugopalan T P Anunasikam/ Jayasankaran Kunjikrishnanmesiri 26 M301 JAY/K Puthuppalli vivahithanayi/ 27 M3 -

Supreme Court of India

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA F.No.5/AC/Panel/2020-2022/SCI(II-A) New Delhi, Dated the 18th July, 2020 NOTICE In pursuance of the notice dated 23rd January, 2020, inviting applications from Senior Advocates, Advocates-on-Record and non- Advocates-on-Record for formation of panels of advocates to act as amicus curiae for use of the Registry for a period of two years i.e., from 1st April, 2020 till 31st March, 2022, and consequent upon the directions of the Competent Authority, the advocates mentioned in List ‘A1’, List ‘B1’ and List ‘C1’ have been empanelled to act as amicus curiae for the said period and the advocates in List ‘A2’, List ‘B2’ and List ‘C2’ shall be on the wait list. Both sets of lists are annexed hereto and have been uploaded on the official website of the Hon’ble Court. Allocation of cases to the Senior Advocates, Advocates-on-Record and non-Advocates-on-Record will be made in the chronological order. The existing ratio of 2:1 between Advocates-on-Record and non- Advocates-on-Record will be maintained by the Registry in the matter of allocation of cases. No request for empanelment as amicus curiae for the aforesaid period hereafter will be entertained. …2/- :: 2 :: In case any Advocate-on-Record / non-Advocate-on-Record, upon allocation of case/s, would not file the required number of paper-books within the time specified for that purpose, or would not respond to the request made by the Registry within a reasonable time, or would return the allocated cases without giving any cogent and convincing reason, or would not appear before the Hon’ble Court, his/her name would be deleted from the panel after obtaining the orders of the Competent Authority. -

Malayalam - Novel

NEW BOMBAY KERALEEYA SAMAJ , LIBRARY LIBRARY LIST MALAYALAM - NOVEL SR.NO: BOOK'S NAME AUTHOR TYPE 4000 ORU SEETHAKOODY A.A.AZIS NOVEL 4001 AADYARATHRI NASHTAPETTAVAR A.D. RAJAN NOVEL 4002 AJYA HUTHI A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4003 UPACHAPAM A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4004 ABHILASHANGELEE VIDA A.P.I. SADIQ NOVEL 4005 GREEN CARD ABRAHAM THECKEMURY NOVEL 4006 TARSANUM IRUMBU MANUSHYARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4007 TARSANUM KOLLAKKARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4008 PATHIMOONNU PRASNANGAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4009 ABC NARAHATHYAKAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4010 HARITHABHAKALKK APPURAM AKBAR KAKKATTIL NOVEL 4011 ENMAKAJE AMBIKA SUDAN MANGAD NOVEL 4012 EZHUTHATHA KADALAS AMRITA PRITAM NOVEL 4013 MARANA CERTIFICATE ANAND NOVEL 4014 AALKKOOTTAM ANAND NOVEL 4015 ABHAYARTHIKAL ANAND NOVEL 4016 MARUBHOOMIKAL UNDAKUNNATHU ANAND NOVEL 4017 MANGALAM RAHIM MUGATHALA NOVEL 4018 VARDHAKYAM ENDE DUKHAM ARAVINDAN PERAMANGALAM NOVEL 4019 CHORAKKALAM SIR ARTHAR KONAN DOYLE D.NOVEL 4020 THIRICHU VARAVU ASHTAMOORTHY NOVEL 4021 MALSARAM ASHWATHI NOVEL 4022 OTTAPETTAVARUDEY RATHRI BABU KILIROOR NOVEL 4023 THANAL BALAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4024 NINGAL ARIYUNNATHINE BALAKRISHNAN MANGAD NOVEL 4025 KADAMBARI BANABATTAN NOVEL 4026 ANANDAMADAM BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJI NOVEL 4027 MATHILUKAL VIKAM MOHAMMAD BASHEER NOVEL 4028 ATTACK BATTEN BOSE NOVEL 4029 DR.DEVIL BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4030 CHANAKYAPURI BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4031 RAKTHA RAKSHASSE BRAM STOCKER NOVEL 4032 NASHTAPETTAVARUDEY SANGAGANAM C.GOPINATH NOVEL 4033 PRAKRTHI NIYAMAM C.R.PARAMESHWARAN NOVEL 4034 CHUZHALI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4035 VERUKAL PADARUNNA VAZHIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4036 ATHIRUKAL KADAKKUNNAVAR C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4037 SAHADHARMINI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4038 KAANAL THULLIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4039 POOJYAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4040 KANGALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4041 THEVADISHI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4042 KANKALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4043 MRINALAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4044 KANNIMANGAKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4045 MALAKAMAAR CHIRAKU VEESHUMBOL C.V. -

Sandhya Suresh V

About Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/about/ Archive: http://www.the-criterion.com/archive/ Contact Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/contact/ Editorial Board: http://www.the-criterion.com/editorial-board/ Submission: http://www.the-criterion.com/submission/ FAQ: http://www.the-criterion.com/fa/ ISSN 2278-9529 Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal Bi-Monthly Refereed and Indexed Open Access eJournal www.galaxyimrj.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English Vol. 8, Issue-VIII, July 2017 ISSN: 0976-8165 Recreation and Representation of History in Subhash Chandran’s A Preface to Man Sandhya Suresh V. Research Scholar, Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, Kalady. Ernakulam, 683574. Article History: Submitted-03/06/2017, Revised-15/07/2017, Accepted-20/07/2017, Published-31/07/2017. Abstract: The paper titled “Recreation and Representation of History in Subhash Chandran’s A Preface to Man” seeks to analyse how well history has been represented in Subhash Chandran’s phenomenal novel A Preface to Man (2015). This is a generational story as it explores the lives of three generations of Ayyatumpilli family: Narapilla, his children, and grandchildren. The novel progresses through the letters written by Jithendran alias Jithen to his wife Ann Mary during their six-year courtship. Thachanakkara is a microcosm of Kerala or rather the entire world. Subhash Chandran places the characters in the past thereby making them a part of the history. The novel informs the readers of the major events, twists, and turns that occurred in the history of Kerala. It also presents a vivid picture of the caste system which prevails in Kerala, and India as a whole. -

Mahatma Gandhi University Syllubus for English Language and Literature (Model 1) 2017 Admissions Onwards

MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY SYLLUBUS FOR ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE (MODEL 1) 2017 ADMISSIONS ONWARDS SCHEME Credits Title Course Category/Code Week Exam Internal Internal External External Semester Hours Per Hours Assessment 1 Common Course-1 Fine-tune Your English 5 4 20 80 EN1CC01 1 Common Course -2 Pearls from the Deep 4 3 20 80 EN1CC02 1 Second Language Common Course 4 4 20 80 1 Methodology for Studying Core Course-1 6 4 20 80 Literature EN1CR01 1 World History/Political Complementary Course 6 4 20 80 Science 2 Common Course -3 Issues that Matter 5 4 20 80 EN2CC03 2 Common Course -4 Savouring the Classics 4 3 20 80 EN2CC04 2 Introducing Language and Core Course -2 6 4 20 80 Literature EN2CR02 2 Second Language Common Course 4 4 20 80 2 History /Political Science Complementary Course 6 4 20 80 3 Common Course -5 Literature and/as Identity 5 4 20 80 EN3CC05 3 Second Language Common Course 5 4 20 80 3 Core Course -3 Harmony of Prose 4 4 20 80 EN3CR03 3 Core Course -4 Symphony of Verse 5 4 20 80 EN3CR04 3 Evolution of Literary Complementary Course 3 Movements: the Shapers of - EN3CM03 6 4 20 80 Destiny 4 Common Course -6 Illuminations 5 4 20 80 EN4CC06 4 Common Course Second Language 5 4 20 80 4 Core Course -5 Modes of Fiction 4 4 20 80 EN4CR05 4 Core Course -6 Language and Linguistics 5 4 20 80 EN4CR06 4 Evolution of Literary Complementary Course 4 6 4 20 80 Movements: the Cross - EN4CM04 1 Currents of Change 5 EN5CROP01 Appreciating Films EN5CROP02 Open Course 4 3 20 80 Theatre Studies EN5CROP03 English for Careers 5 Core Course -

Malayalam - Short Stories

NEW BOMBAY KERALEEYA SAMAJ , LIBRARY LIBRARY LIST MALAYALAM - SHORT STORIES SR.NO: BOOK'S NAME AUTHOR TYPE 3001 NADAN VAMOZHIKAL A.B.V.KAVILPADU STORIES 3002 THAKAZHIYILE VELLAPOKKATHIL OZHUKI OZHUKI ORU A.M.MOHAMMAD MANASSU 3003 KADAL VEZHUNGIA KUKRI AIR COMMANDOR S.NAIR STORIES 3004 SHESHAM SCREENIL AKBAR KAKKATTIL STORIES 3005 ANTON CHEKKOVU ANTON CHEKKOVU STORIES 3006 GRIMMINDE KADHAKAL( ARAM BHAGAM) ASHAMANNOOR HARIHARAN STORIES 3007 GRIMMINDE KADHAKAL( ESHAM BHAGAM) ASHAMANNOOR HARIHARAN STORIES 3008 THIRANJEDUTHA KADAM KADHAKAL 1001 BALASAHITHI PRAKASHAN STORIES 3009 VIKRAMADITHYA KATHAKAL C.MADHAVAN PILLA STORIES 3010 NERU, ONNAM SAKSHI NAN THANNE C.P.NAIR STORIES 3011 DUKHITHARUDE DHUKKAM C.V.SREERAMAN STORIES 3012 ENDOCY VALLYAMMA C.V.SREERAMAN STORIES 3013 KADHAKAL C.V.SREERAMAN STORIES 3014 ORMA CHEPPU C.V.SREERAMAN STORIES 3015 ALAMARAYIL PAMBU CHELAGATTU GOPALAKRISHNAN STORIES 3016 VENAL CHELLAMMA JOSEPH STORIES 3017 GRIHA THURA KADHAKAL CHEPPAD SOMANATHAN STORIES 3018 MANI MEGHALAYUDE KADHA CHITHALAI CHATHANAAR STORIES 3019 SMRITHIKAL MURIVUKAL DR.MURALI KRISHNA STORIES 3020 THAMARAKULATHE AMMUKUTTY E.V.SREEDHARAN STORIES 3021 ENTE MINIKADHAKAL E.V.SREEDHARAN STORIES 3022 UTHARADHUNIK KADHA EDITOR N.G.BABU STORIES 3023 8.49 FAST EZHIKARA AMBUJAKSHAN STORIES 3024 MUMBAI KADHAKAL F.O.MA MUMBAI STORIES 3025 KALLA KATHANAAR G.THALIAN STORIES 3026 OTTA SNAPPIL ODHUKKANAVILLA ORU JANMA GEETHA HIRANYAN STORIES SATHYAM 3027 NARAKA VATHIL GRACY STORIES 3028 KULASTHRIYUDE KOLAPATHAKAM HAMEED STORIES 3029 SANK PARIVAR INDU MENON STORIES -

An Imprint of Harpercollins Publishers 1

@HarperCollinsIN An Imprint of HarperCollins Publishers 1 Let’s Talk Translation! Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, showcases the finest writing from the various languages of the Indian subcontinent in English translation. Here is a library of powerful writers and books that will go on to become classics; here is a wealth of writing in translation; here are stories, anti-stories, novels, poetry, political manifestos, travelogues and memoirs. Harper Perennial is as much about literature that is rooted, as it is about finding ways to make it travel. So, as an additional feature, every title comes with a P.S. Section that allows readers to explore the books more intimately through translator’s notes, essays and author interviews. 2 3 CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF HARPER PERENNIAL IN INDIA FROM THE PUBLISHER'S DESK In 2017, Harper Perennial, a dedicated imprint for translations, completes ten years of publishing in India. Over the past decade, Perennial books have showcased the finest and most compelling narratives from the Indian languages, books that are timeless and stories that capture the essence of their times and the region from which they emanate. In its entirety, the Perennial library which features over a hundred titles presents the kaleidoscope of India as seen through the eyes of the greatest modern writers writing in the local languages, comprising award-winning and well-loved novels, short fiction, poetry, plays, memoirs, biographies and travelogues. Over the last few months, Harper Perennial has published a select list of titles in translation that readers will have enjoyed – including Gulzar’s first novel Two and his collection of Partition writings Footprints on Zero Line, Rabindranath Tagore’s The Boat-wreck, Kiran Nagarkar’s first novel Seven Sixes Are Forty-three, Ranjit Desai’s Shivaji: The Great Maratha, Pran Kishore’s Gul Gulshan Gulfam, Vinod Kumar Shukla’s Moonrise from the Green Grass Roof, Rahi Masoom Raza’s Scene: 75, and Jayant Kaikini’s book of Mumbai stories No Presents Please. -

Media Handbook 2019

MEDIA HANDBOOK 2019 Information & Public Relations Department Government of Kerala MEDIA HANDBOOK 2019 Information & Public Relations Department Government of Kerala Chief Editor T V Subhash IAS Co-ordinating Editor P S Rajasekharan Deputy Chief Editor K P Saritha Editor Manoj K. Puthiyavila Copy Editor T S Divya Editorial assistance Ruban M Paul S Manikantan Cover Design Godfrey Das Circulation Officer Preeya Unnikrishnan Printed at Orange Press, Pvt. Ltd., Thiruvananthapuram Compiled and Edited by the Research and Reference Wing, Information and Public Relations Department, Government of Kerala. Printed and Published by the Director, I&PRD. February 6, 2019 For Private Circulation Only Number of Copies: 8,000 The content of this book is updated upto 30/01/2019 Disclaimer : Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information provided in this Hand Book. However, it is possible that it may not be representative of the whole body of facts available and resources may contain errors or out-of-date information. Not to be used for any legal purpose as an authentic data. No responsibility can be accepted by the I&PR Department for any action taken on the basis of this information. PERSONAL MEMORANDA Name ............................................................................................................. Address Office Residence ............................... ......................................... ............................... ......................................... ............................... ........................................ -

Malayalam Books in Surrey Library

Malayalam Books at Surry Public Library City Center Branch - World Languages Section No: Title Author Publishers Category 1 101 Sanjayan Phalithangal Sanjayan D.C. Books Humor 2 25 Asadharana jeevithangal Thaha Madai Biography 3 5 Minutes Kadhakal Maali D.C. Books Children's Literature Sahithy 4 Aana Kathakal Kottarathil Shankunni pravarthaka Arctile Collections 5 Aanavaariyum Ponkurishum Basheer D.C. Books Novel 6 Akkithathinte Kuttikavithakal Akkitham D.C. Books Children's Literature 7 Ambedkar- Oru padanam Dalit Bandu 8 Anunasikam T. P. Venugopalan 9 Aparahnam O.N.V D.C. Books Poems Asanum Keralathile Samoohika Sahithy 10 Viplavavum T. K. Ravindran pravarthaka History 11 Aswamedham Thoppil Bhasi D.C. Books Stage Drama 12 Aum 13 Basheer Phalithangal Azeez Tharuvana Olive Humor 14 Chandaalabhikshuki Kumaranashan D.C. Books Poems Sahithy 15 Chitha Kadakkunna Thumpikal P Unnikrishnan Kallil pravarthaka Novel 16 Chora sasthram V J Jaimes Novel 17 Chullikkaadhinte Kavithakal Balachandran ChullikkaduD.C. Books Poems 18 Cleopatrayude Nattil S.K. Pottakkadu Mathrubhoomi Travel Diaries 19 Delhi Gathakal M Mukundan Novel 20 Ente Aadhyathe Kadhakal T. Padmanabhan H & C Short Stories 21 Ente Priyapetta Kadhakal C.V. Balakrishnan D.C. Books Short Stories 22 Ente Priyapetta kannanthalippukal Saara Thomas Current Books Short Stories 23 Ezhivalayude Thazvarangal Sunilkumar K N novel Father Damien - Kustarogikalude 24 apposthalan Premjith Kayamkulam National Jeevacharitham G. Shankarakuruppinte Thiranjedutha 25 Kavithakal G. Sankarakuruppu D.C. Books Poems 26 Ghatikarangal Nilaykkunna Samayam Subhash Chandran D.C. Books Short Stories 27 Gurusaagaram O.V.Vijayan D.C. Books Novel 28 Hay Rama Mahan Kumar Sahithy 29 Jeevitham Oru Samaram Akkamma Cheriyan pravarthaka Jeevacharitham 30 Kadalchorukku C Anoop Short stories 31 Kadammanittayude Kavithakal Kadammanitta D.C. -

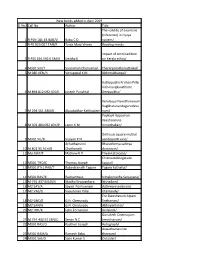

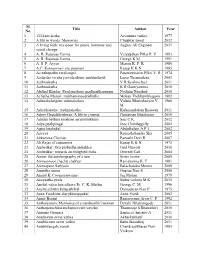

List of Biographies Availabe in KCHR Archive

Sl. Title Author Year No. 1 1114-nte katha Accamma varkey 1977 2 A life in words: Memories Chughtai Ismat 2012 3 A living faith: my quest for peace, harmony and Asghar Ali Engineer 2011 social change 4 A. R. Rajaraja Varma Velayudhan Pillai P. V 1993 5 A. R. Rajaraja Varma George K M 1991 6 A. S. P. Ayyar Menon K. P. K 1980 7 A.C. Kannan nair oru patanam Kurup K K N 1985 8 Aa ezhupathu varshangal Parameswaran Pillai V. R 1974 9 Aadarsha vivaha jeevithathinte anubhuthiyil Lazar Thermadam 2003 10 Aathmakatha V R Krishna Iyer 2011 11 Aathmakatha K R Gauriyamma 2010 12 Abdhul Khadar: Paadanothoru madhurithaganam Nadhim Naushad 2010 13 Achutha Menon: mukhammoodiyillathe Mohan Thekkumbhagom 1992 14 Adimakalengane udamakalaye Vishnu Bharatheeyan V. 1980 M 15 Adiyitharathe: Aathmakatha Kalamandalam Kesavan 2011 16 Adoor Gopalakrishnan: A life in cinema Gautaman Bhaskaran 2010 17 Aduthu bellinu natakam aarambhikkum Sasi C K 2012 18 Adya pushpangal Jose Chittilappilly 2002 19 Agnichirakukal Abdulkalam A P J 2002 20 Agyeya Rameshchandra Sha 2005 21 Akkamma Cherian Parvathi Devi R 2007 22 Ali Rajas of cannanore Kurup K K N 1975 23 Ambedkar: Oru prabudha indiakkai Gail Omvedt 2010 24 Ambedkar: towards an enlighted India Omvedt Gail 2004 25 Amen: the autobiography of a nun Sister Jesme 2009 26 Ammannoor chachu chakyar Ramavarma K. T 1981 27 Ammayane Sathyam Balachandra Menon 2009 28 Amrutha smrui Guptan Nair S 2006 29 Anand K. Coomaraswamy Jag Mohan 1979 30 Anayaatha jwala Shibu vaikom M K 2015 31 Anchal valiachan adhava Fr. C.