Opposition to Motion to Dismiss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gamble: the Three Nested Investigations

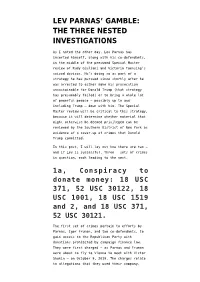

LEV PARNAS’ GAMBLE: THE THREE NESTED INVESTIGATIONS As I noted the other day, Lev Parnas has inserted himself, along with his co-defendants, in the middle of the presumed Special Master review of Rudy Giuliani and Victoria Toensing’s seized devices. He’s doing so as part of a strategy he has pursued since shortly after he was arrested to either make his prosecution unsustainable for Donald Trump (that strategy has presumably failed) or to bring a whole lot of powerful people — possibly up to and including Trump — down with him. The Special Master review will be critical to this strategy, because it will determine whether material that might otherwise be deemed privileged can be reviewed by the Southern District of New York as evidence of a cover-up of crimes that Donald Trump committed. In this post, I will lay out how there are two — and if Lev is successful, three — sets of crimes in question, each leading to the next. 1a, Conspiracy to donate money: 18 USC 371, 52 USC 30122, 18 USC 1001, 18 USC 1519 and 2, and 18 USC 371, 52 USC 30121. The first set of crimes pertain to efforts by Parnas, Igor Fruman, and two co-defendants, to gain access to the Republican Party with donations prohibited by campaign finance law. They were first charged — as Parnas and Fruman were about to fly to Vienna to meet with Victor Shokin — on October 9, 2019. The charges relate to allegations that they used their company, Global Energy Partners, to launder money, including money provided by a foreigner, to donate to Trump-associated and other Republican candidates. -

1 January 20, 2021 Attorney Grievance Committee Supreme

January 20, 2021 Attorney Grievance Committee Supreme Court of the State of New York Appellate Division, First Judicial Department 180 Maiden Lane New York, New York 10038 (212) 401-0800 Email: [email protected] Re: Professional Responsibility Investigation of Rudolph W. Giuliani, Registration No. 1080498 Dear Members of the Committee: Lawyers Defending American Democracy (“LDAD”) is a non-profit, non-partisan organization the purpose of which is to foster adherence to the rule of law. LDAD’s open letters and statements calling for accountability on the part of public officials have garnered the support of 6,000 lawyers across the country, including many in New York.1 LDAD and the undersigned attorneys file this ethics complaint against Rudolph W. Giuliani because Mr. Giuliani has violated multiple provisions of the New York Rules of Professional Conduct while representing former President Donald Trump and the Trump Campaign. This complaint is about law, not politics. Lawyers have every right to represent their clients zealously and to engage in political speech. But they cross ethical boundaries—which are equally boundaries of New York law—when they invoke and abuse the judicial process, lie to third parties in the course of representing clients, or engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or misrepresentation in or out of court. By these standards, Mr. Giuliani’s conduct should be investigated, and he should be sanctioned immediately while the Committee investigates. As lead counsel for Mr. Trump in all election matters, Mr. Giuliani has spearheaded a nationwide public campaign to convince the public and the courts of massive voter fraud and a stolen presidential election. -

Digenovaarticle

The Oral History of the Outspoken Joseph diGenova By interviewer Carl Stern Joseph diGenova is a subject for whom no interviewing skills are necessary as he proved in an oral history taken in 2003. He has a no-holds-barred viewpoint on just about everything. Take, for example, his opinion on electing judges, “it’s a terrible system.” Or his description of Washington D.C.: “A small southern town with sixty-two square miles of gossip” but “no better place to be.” His advice to young lawyers is to spend a portion of their careers as he did: “Anybody who wants to be a Washington lawyer has to spend some time on the Hill.” Naturally his favorite politician was Maryland Republican Senator Charles “Mac” Mathias, for whom he worked. DiGenova, a former United States Attorney for the District of Columbia, has plenty to say about the legal system. He gives higher marks to the criminal bar than civil. “More ethical,” he says. He calls the civil system broken -- “a battle of paperwork and motions unrelated to a search for the truth.” In fact, he says, “Lawyers view their role as preventing finding out the truth,” for fear it will hurt their client. Although he has been a trial lawyer for much of his career, diGenova declares, “Litigation is a big waste of time, for the most part. It doesn’t solve many problems. We have created the image that every single thing that is wrong with America can be settled by a lawsuit – and that is a big mistake.” He blames trial judges for some of the problem. -

Benghazi.Pdf

! 1! The Benghazi Hoax By David Brock, Ari Rabin-Havt and Media Matters for America ! 2! The Hoaxsters Senator Kelly Ayotte, R-NH Eric Bolling, Host, Fox News Channel Ambassador John Bolton, Fox News Contributor, Foreign Policy Advisor Romney/Ryan 2012 Gretchen Carlson, Host, Fox News Channel Representative Jason Chaffetz, R-UT Lanhee Chen, Foreign Policy Advisor, Romney/Ryan 2012 Joseph diGenova, Attorney Steve Doocy, Host, Fox News Channel Senator Lindsay Graham, R-SC Sean Hannity, Host, Fox News Channel Representative Darrell Issa, R-CA, Chairman, House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Brian Kilmeade, Host, Fox News Channel Senator John McCain, R-AZ Mitt Romney, Former Governor of Massachusetts, 2012 Republican Presidential Nominee Stuart Stevens, Senior Advisor, Romney/Ryan 2012 Victoria Toensing, Attorney Ambassador Richard Williamson, Foreign Policy Advisor, Romney/Ryan 2012 ! 3! Introduction: Romney’s Dilemma Mitt Romney woke up on the morning of September 11, 2012, with big hopes for this day – that he’d stop the slow slide of his campaign for the presidency. The political conventions were in his rear-view mirror, and the Republican nominee for the White House was trailing President Obama in most major polls. In an ABC News/Washington Post poll released at the start of the week, the former Massachusetts governor’s previous 1-point lead had flipped to a 6-point deficit.1 “Mr. Obama almost certainly had the more successful convention than Mr. Romney,” wrote Nate Silver, the polling guru and then-New York Times blogger.2 While the incumbent’s gathering in Charlotte was marked by party unity and rousing testimonials from Obama’s wife, Michelle, and former President Bill Clinton, Romney’s confab in Tampa had fallen flat. -

Marketing Ties to Trump, Top Donor Made Millions

C M Y K Nxxx,2018-03-26,A,001,Bs-4C,E2 Late Edition Today, sunshine and patchy clouds, rather cool for late March, high 48. Tonight, clear, cold, low 32. Tomor- row, plenty of sunshine, high 50. Weather map appears on Page D8. VOL. CLXVII ... No. 57,913 © 2018 The New York Times Company NEW YORK, MONDAY, MARCH 26, 2018 $3.00 Marketing Ties to Trump, Top Donor Made Millions Offers of Private Parties With the President, Sent With Proposed Business Deals By KENNETH P. VOGEL and DAVID D. KIRKPATRICK WASHINGTON — For Elliott tarian facing corruption charges, Broidy, Donald J. Trump’s presi- who posted a photograph with the dential campaign represented an president on Facebook. unparalleled political and busi- This type of access has value on ness opportunity. the international stage, where the An investor and defense con- perception of support from an tractor, Mr. Broidy became a top American president — or even a fund-raiser for Mr. Trump’s cam- photo with one — can benefit for- paign when most elite Republican eign leaders back home. donors were keeping their dis- Mr. Broidy was open about his tance, and Mr. Trump in turn over- business interests, but the admin- looked the lingering whiff of scan- istration made no effort to curtail dal from Mr. Broidy’s 2009 guilty his offers of access to clients or plea in a pension fund bribery prospective clients. case. Yet Mr. Broidy was so ag- After Mr. Trump’s election, Mr. gressive, some associates said, Broidy quickly capitalized, mar- that they warned him to tone keting his Trump connections to down his approach for fear that he politicians and governments might run afoul of the president, around the world, including some clients or American lobbying and with unsavory records, according to interviews and documents ob- anti-corruption laws. -

October 8, 2019 VIA EMAIL U.S. Department of State Office Of

October 8, 2019 VIA EMAIL U.S. Department of State Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL SA-2, Suite 8100 Washington, DC 20522-0208 [email protected] Re: Expedited Freedom of Information Act Request Dear FOIA Officer: Pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), 5 U.S.C. § 552, and the implementing regulations of your agency, American Oversight makes the following request for records. On May 9, 2019, President Trump’s personal lawyer, Rudolph Giuliani, announced that he would travel to Ukraine to meet with the country’s president-elect to urge the Ukrainian government to pursue an investigation related to the son of former Vice President Biden— a potential electoral opponent of the president.1 Mr. Giuliani, reportedly aided by the president’s former attorneys Victoria Toensing and Joseph E. diGenova, defended his planned trip by stating that “[w]e’re not meddling in an election, we’re meddling in an investigation.”2 After facing widespread criticism for this effort to influence a foreign government’s law enforcement efforts for political gain, Mr. Giuliani canceled his trip to Ukraine.3 Subsequent reports indicate that Mr. Giuliani engaged a State Department official—U.S. Special Representative for Ukraine Negotiations Kurt D. Volker—in his efforts.4 The State Department has acknowledged that Mr. Volker helped arrange talks 1 Kenneth P. Vogel, Rudy Giuliani Plans Ukraine Trip to Push for Inquiries That Could Help Trump, N.Y. TIMES, May 9, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/09/us/politics/giuliani- ukraine-trump.html. 2 Id. -

The War on Whistleblowers

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA JOURNAL of LAW & PUBLIC AFFAIRS Vol. 6 April 2021 No. 4 THE WAR ON WHISTLEBLOWERS Nancy M. Modesitt * In the last few decades, Congress has passed a variety of statutes to improve legal protections for federal employee-whistleblowers, with the dual goals of promoting disclosure of wrongdoing and prohibiting retaliation against whistleblowers. However, these statutes and goals were undermined during the Trump administration. This Article argues that President Trump’s administration conducted multi-faceted attacks against federal employee- whistleblowers in order to deter disclosure of the administration’s wrongdoing. Since these efforts began, there has been a decrease in whistleblower disclosures of wrongdoing in the federal government. In order to stop this trend, immediate action is needed, including amending federal laws to reduce the possibility of retaliation by administration officials against whistleblowers, increasing funding and staffing at the federal agencies tasked with protecting whistleblowers and adjudicating their retaliation claims, and promoting greater outreach by congressional committees to federal employees within agencies over which such committees have oversight authority. If these steps are not taken, there is a significant risk that the culture of promoting whistleblowing that has been cultivated within the federal government will collapse, leaving the American public in the dark about future misconduct within the Executive branch of the government. * Nancy M. Modesitt is a Professor of Law at the University of Baltimore School of Law. Professor Modesitt is grateful for the efforts of her research assistants, Patrick Brooks and Zachary Jones, as well as Carly Roche, one of our reference librarians, for their assistance on this Article. -

Impeachment Inquiry Report

TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .......................................................................................................................................7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................................12 KEY FINDINGS OF FACT ........................................................................................................34 SECTION I. THE PRESIDENT’S MISCONDUCT ...............................................................37 1. The President Forced Out the U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine ...........................................38 2. The President Put Giuliani and the Three Amigos in Charge of Ukraine Issues ............51 3. The President Froze Military Assistance to Ukraine .......................................................67 4. The President’s Meeting with the Ukrainian President Was Conditioned on An Announcement of Investigations .....................................................................................83 5. The President Asked the Ukrainian President to Interfere in the 2020 U.S. Election by Investigating the Bidens and 2016 Election Interference ................................................98 6. The President Wanted Ukraine to Announce the Investigations Publicly ....................114 7. The President’s Conditioning of Military Assistance and a White House Meeting on Announcement of Investigations Raised Alarm ............................................................126 8. The President’s Scheme Was Exposed ..........................................................................140 -

1 United States District Court for the District

Case 1:19-cv-02934-CRC Document 1 Filed 10/01/19 Page 1 of 10 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) AMERICAN OVERSIGHT, ) 1030 15th Street NW, B255 ) Washington, DC 20005 ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Case No. 19-cv-2934 ) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, ) 2201 C Street NW ) Washington, DC 20520 ) ) Defendant. ) ) COMPLAINT 1. Plaintiff American Oversight brings this action against the U.S. Department of State under the Freedom of Information Act, 5 U.S.C. § 552 (FOIA), and the Declaratory Judgment Act, 28 U.S.C. §§ 2201 and 2202, seeking declaratory and injunctive relief to compel compliance with the requirements of FOIA. JURISDICTION AND VENUE 2. This Court has jurisdiction over this action pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(B) and 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331, 2201, and 2202. 3. Venue is proper in this district pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(B) and 28 U.S.C. § 1391(e). 4. Because Defendant has failed to comply with the applicable time-limit provisions of the FOIA, American Oversight is deemed to have exhausted its administrative remedies pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(6)(C)(i) and is now entitled to judicial action enjoining the agency 1 Case 1:19-cv-02934-CRC Document 1 Filed 10/01/19 Page 2 of 10 from continuing to withhold agency records and ordering the production of agency records improperly withheld. PARTIES 5. Plaintiff American Oversight is a nonpartisan, non-profit section 501(c)(3) organization primarily engaged in disseminating information to the public. -

A Very Stable Genius at That!” Trump Invoked the “Stable Genius” Phrase at Least Four Additional Times

PENGUIN PRESS An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com Copyright © 2020 by Philip Rucker and Carol Leonnig Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019952799 ISBN 9781984877499 (hardcover) ISBN 9781984877505 (ebook) Cover design by Darren Haggar Cover photograph: Pool / Getty Images btb_ppg_c0_r2 To John, Elise, and Molly—you are my everything. To Naomi and Clara Rucker CONTENTS Title Page Copyright Dedication Authors’ Note Prologue PART ONE One. BUILDING BLOCKS Two. PARANOIA AND PANDEMONIUM Three. THE ROAD TO OBSTRUCTION Four. A FATEFUL FIRING Five. THE G-MAN COMETH PART TWO Six. SUITING UP FOR BATTLE Seven. IMPEDING JUSTICE Eight. A COVER-UP Nine. SHOCKING THE CONSCIENCE Ten. UNHINGED Eleven. WINGING IT PART THREE Twelve. SPYGATE Thirteen. BREAKDOWN Fourteen. ONE-MAN FIRING SQUAD Fifteen. CONGRATULATING PUTIN Sixteen. A CHILLING RAID PART FOUR Seventeen. HAND GRENADE DIPLOMACY Eighteen. THE RESISTANCE WITHIN Nineteen. SCARE-A-THON Twenty. AN ORNERY DIPLOMAT Twenty-one. GUT OVER BRAINS PART FIVE Twenty-two. AXIS OF ENABLERS Twenty-three. LOYALTY AND TRUTH Twenty-four. THE REPORT Twenty-five. THE SHOW GOES ON EPILOGUE Acknowledgments Notes Index About the Authors AUTHORS’ NOTE eporting on Donald Trump’s presidency has been a dizzying R journey. Stories fly by every hour, every day. -

August 23, 2019 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL U.S. Department of State

August 23, 2019 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL U.S. Department of State Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL SA-2, Suite 8100 Washington, DC 20522-0208 [email protected] Re: Freedom of Information Act Request Dear Freedom of Information Officer: Pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), 5 U.S.C. § 552, and the implementing regulations of the Department of State (State), 22 C.F.R. Part 171, American Oversight makes the following request for records. On May 9, 2019, President Trump’s personal lawyer, Rudolph Giuliani, announced that he would travel to Ukraine to meet with the country’s president-elect to urge the Ukrainian government to pursue an investigation related to the son of former Vice President Biden—a potential electoral opponent of the president.1 Mr. Giuliani, reportedly aided by the president’s former attorneys Victoria Toensing and Joseph E. diGenova, defended his planned trip by stating that “[w]e’re not meddling in an election, we’re meddling in an investigation.”2 After facing widespread criticism for this effort to influence a foreign government’s law enforcement efforts for political gain, Mr. Giuliani canceled his trip to Ukraine.3 It is more troubling that, shortly before Mr. Giuliani announced his plan to attempt to “meddl[e]” in a Ukrainian investigation related to one of the president’s potential political opponents, State recalled U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine Marie Yovanovitch, a career foreign service officer who has served under Democratic and Republican presidents.4 Ambassador Yovanovitch had faced criticism 1 Kenneth P. Vogel, Rudy Giuliani Plans Ukraine Trip to Push for Inquiries That Could Help Trump, N.Y. -

S Joint Defense Agreement with the Russian Mob

THE PRESIDENT’S JOINT DEFENSE AGREEMENT WITH THE RUSSIAN MOB If we survive Trump and there are still things called museums around that display artifacts that present things called facts about historic events, I suspect John Dowd’s October 3 letter to the House Intelligence Committee will be displayed there, in all its Comic Sans glory. In it, Dowd memorializes a conversation he had with HPSCI Investigation Counsel Nicholas Mitchell on September 30, before he was officially the lawyer for Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman, now placed in writing because he had since officially become their lawyer. He describes that there is no way he and his clients can comply with an October 7 document request and even if he could — this is the key part — much of it would be covered by some kind of privilege. Be advised that Messrs. Parnas and Fruman assisted Mr. Giuliani in connection with his representation of President Trump. Mr. Parnas and Mr. Fruman have also been represented by Mr. Giuliani in connection with their personal and business affairs. They also assisted Joseph DiGenova and Victoria Toensing in their law practice. Thus, certain information you seek in your September 30, 2019, letter is protected by the attorney-client, attorney work product and other privileges. Once that letter was sent, under penalty of prosecution for false statements to Congress, it became fact: Parnas and Fruman do work for Rudy Giuliani in the service of the President of the United States covered by privilege, Rudy does work for them covered by privilege, and they also do work for Joseph Di Genova and Victoria Toensing about this matter that is covered by privilege.