Erev Yom Kippur - 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of the Jewish Prayerbook'

"We Are Bound to Tradition Yet Part of That Tradition Is Change": The Development of the Jewish Prayerbook' Ilana Harlow Indiana University The traditional Jewish liturgy in its diverse manifestations is an imposing artistic structure. But unlike a painting or a symphony it is not the work of one artist or even the product of one period. It is more like a medieval cathedral, in the construction of which many generations had a share and in the ultimate completion of which the traces of diverse tastes and styles may be detected. (Petuchowski 1985:312) This essay explores the dynamics between tradition and innovation, authority and authenticity through a study of a recently edited Jewish prayerbook-a contemporary development in a tradition which can be traced over a one-thousand year period. The many editions of the Jewish prayerbook, or siddur, that have been compiled over the centuries chronicle the contributions specific individuals and communities made to the tradition-informed by the particular fashions and events of their times as well as by extant traditions. The process is well-captured in liturgist Jakob Petuchowski's 'cathedral simile' above-an image which could be applied equally well to many traditions but is most evident in written ones. An examination of a continuously emergent written tradition, such as the siddur, can help highlight kindred processes involved in the non-documented development of oral and behavioral traditions. Presented below are the editorial decisions of a contemporary prayerbook editor, Rabbi Jules Harlow, as a case study of the kinds of issues involved when individuals assume responsibility for the ongoing conserva- tion and construction of traditions for their communities. -

Flint Orchestra

Flint SymphonyOrchestra A Program of the Flint Institute of Music ENRIQUE DIEMECKE, MUSIC DIRECTOR & CONDUCTOR MAY 8, 2021 FIM SEASON SPONSOR Whiting Foundation CONCERT SPONSORS Mr. Edward Davison, Attorney at Law & Dr. Cathy O. Blight, Dr. Brenda Fortunate & C. Edward White, Mrs. Linda LeMieux, Drs. Bobby & Nita Mukkamala, Dr. Mark & Genie Plucer Flint Symphony Orchestra THEFSO.ORG 2020 – 21 Season SEASON AT A GLANCE Flint Symphony Orchestra Flint School of Performing Arts Flint Repertory Theatre STRAVINSKY & PROKOFIEV FAMILY DAY SAT, FEB 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Cathy Prevett, narrator SAINT-SAËNS & BRAHMS SAT, MAR 6, 2021 @ 7:30PM Noelle Naito, violin 2020 William C. Byrd Winner WELCOME TO THE 2020 – 21 SEASON WITH YOUR FLINT SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA! BEETHOVEN & DVOŘÁK SAT, APR 10, 2021 @ 7:30PM he Flint Symphony Orchestra (FSO) is one of Joonghun Cho, piano the finest orchestras of its size in the nation. BRUCH & TCHAIKOVSKY TIts rich 103-year history as a cultural icon SAT, MAY 8, 2021 @ 7:30PM in the community is testament to the dedication Julian Rhee, violin of world-class performance from the musicians AN EVENING WITH and Flint and Genesee County audiences alike. DAMIEN ESCOBAR The FSO has been performing under the baton SAT, JUNE 19, 2021 @ 7:30PM of Maestro Enrique Diemecke for over 30 years Damien Escobar, violin now – one of the longest tenures for a Music Director in the country. Under the Maestro’s unwavering musical integrity and commitment to the community, the FSO has connected with audiences throughout southeast Michigan, delivering outstanding artistry and excellence. All dates are subject to change. -

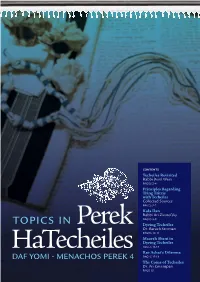

TOPICS in Perek

CONTENTS Techeiles Revisited Rabbi Berel Wein PAGES 2-4 Principles Regarding Tying Tzitzis with Techeiles Collected Sources PAGES 5-7 Kala Ilan Rabbi Ari Zivotofsky PAGES 8-9 TOPICS IN Dyeing Techeiles Perek Dr. Baruch Sterman PAGES 10-11 Maareh Sheni in Dyeing Techeiles PAGES 12-13 HaTecheiles Rav Achai’s Dilemna DAF YOMI • MENACHOS PEREK 4 PAGES 12-13 The Coins of Techeiles Dr. Ari Greenspan PAGE 15 Techeiles Revisited “Color is an emotional Rabbi Berel Wein experience. Techeiles ne of the enduring mysteries of Jewish life following the exile of the is the emotional Jews from the Land of Israel was the disappearance of the string of Otecheiles in the tzitzis garment that Jews wore. Techeiles was known reminder of the bond to be of a blue color while the other strings of the tzitzis were white in color. Not only did Jews stop wearing techeiles but they apparently even forgot how between ourselves and it was once manufactured. The Talmud identified techeiles as being produced Hashem and how we from the “blood” of a sea creature called the chilazon. And though the Talmud did specify certain traits and identifying characteristics belonging to the get closer to Hashem chilazon, the description was never specific enough for later generations of Jews to unequivocally determine which sea creature was in fact the chilazon. with Ahavas Hashem, It was known that the chilazon was harvested in abundance along the northern coast of the Land of Israel from Haifa to south of Tyre in Lebanon (Shabbos the love of Hashem, 26a). Though techeiles itself disappeared from Jewish life as part of the damage the love of Torah and of exile, the subject of techeiles continued to be discussed in the great halachic works of all ages. -

Rep List 1.Pub

Richmond Symphony Orchestra League Student Concerto Competition Repertoire Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Guitar & percussion students are welcome to participate; Please contact Anne Hoffler, contest coordinator, at aahoffl[email protected] for repertoire approval no later than November 30. VIOLIN Faure Elegy, Op. 24 Bach All Violin concerti Haydn Cello Concerto No. 1 in C major Beethoven Violin Concerto in D major Haydn Cello Concerto No. 2 in D major Beethoven Romance No. 1 in G major Kabalevsky Cello Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 49 Beethoven Romance No. 2 in F major Lalo Cello Concerto in D minor Bériot Scéne de Ballet, Op. 100 Rubinstein Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op.96 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 7 in G major Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op.33 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 9 in A minor Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 119 Bruch Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor Schumann Cello Concerto in A minor Haydn All Violin concerti Shostakovich Concerto for Cello No. 1 Kabalevsky Violin Concerto in C Major, Op. 48 Stamitz All Cello concerti Lalo Symphonie Espagnole R. Strauss Romanze in F major Massenet Méditation from Thaïs Tchaikovsky Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op.33 Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.64 Vivaldi All Cello concerti Mozart Violin Concerto No. 1 in B-flat major Mozart Violin Concerto No. 2 in D major BASS Mozart Violin Concerto No. 3 in G major Bottesini Double Bass Concerto No.2 in B minor Mozart Violin Concerto No. -

String Diplomas Repertoire List

String diplomas repertoire list 1 January 2011 – 31 December 2018 STRING DIPLOMAS 2011–2018 Contents Page LCM Publications ........................................................................................................................ 2 Overview of LCM Diploma Structure ................................................................................. 3 Violin DipLCM in Performance .......................................................................................................... 4 ALCM in Performance .............................................................................................................. 5 LLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 7 FLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 7 Viola DipLCM in Performance .......................................................................................................... 8 ALCM in Performance .............................................................................................................. 9 LLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 10 FLCM in Performance ............................................................................................................... 11 Cello DipLCM in Performance ......................................................................................................... -

Wichita Symphony Youth Orchestras Acceptable Repertoire for Youth Talent Auditions

Wichita Symphony Youth Orchestras Acceptable Repertoire for Youth Talent Auditions Repertoire not listed below may be acceptable, but must be pre-approved. Contact Tiffany Bell at [email protected] to request approval for repertoire not on this list. Violin Bach: Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Bach: Concerto No. 2 in E Major Barber: Concerto, Op. 14, first movement Beethoven: Concerto in D Major, Op. 61 Beethoven: Romance No. 1 in G Major Beethoven: Romance No. 2 in F Major Brahms: Concerto, third movement Bruch: Concerto No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 26, any movement Bruch: Scottish Fantasy Conus: Concerto in E Minor, first movement Dvorak: Romance Haydn: Concerto in C Major, Hob.VIIa Kabalevsky: Concerto, Op. 48, first or third movement Khachaturian: Violin Concert, Allegro Vivace, first movement Lalo: Symphonie Espagnole, first or fifth movement Mendelssohn: Concerto in E Minor, any movement Mozart: Concerto No. 3 in G Major, K. 216, any movement Mozart: Concerto No. 4 in D Major, K. 218, first movement Mozart: Concerto No. 5 in A Major, K. 219, first movement Saint-Saens: Introduction and Rondo Capriccios, Op. 28 Saint-Saens: Concerto No. 3 in B Minor, Op. 61 Saint-Saens: Havanaise Sarasate: Zigeunerweisen, Op. 20 Sibelius: Concerto in D Minor, fist movement Tchaikovsky: Concerto, third movement Vitali: Chaconne Wieniawski: Legend, Op. 17 Wieniawski: Concerto in D Minor Viola J.C. Bach/Casadesus: Concerto in C Minor, Adagio-Allegro Bach: Concerto in D Minor, first movement Forsythe: Concerto for Viola, first movement Handel/Casadesus: Concerto in B Minor Hoffmeister Concerto Stamitz: Concerto in D Major Telemann: Concerto in G Major Cello Boccherini: Concerto Bruch: Kol Nidrei Dvorak: Concerto in B Minor, Op. -

A Short History of the Jewish Fixed Calendar: the Origin of the Molad

133 A Short History of the Jewish Fixed Calendar: The Origin of the Molad By: J. JEAN AJDLER I. Introduction. It was always believed that the transition from the observation to the fixed calendar was clear-cut, with the fixed calendar immediately adopting its definitive form in 358/359, at the date of the inception. Indeed according to a tradition1 quoted in the name of R’ Hai Gaon,2 the present Jewish calendar was introduced by the patriarch Hillel II in the Jewish Year 4119 AM (anno mundi, from creation), 358/359 CE. The only discordant element with regard to this theory that the calen- dar adopted immediately its definitive form, was the fact that we find al- ready in the Talmud that the postponement of Rosh Hashanah from Sun- day was a later enactment.3 Only some rare rabbinic authorities already recognized the later character of this postponement. Indeed a passage of the epistle of R’ Sherira Gaon implying that Rosh Hashanah of the year 505 C.E. was still on Sunday was generally consid- ered as the result of a copyist mistake.4 It is only in the first decade of the twentieth century that new evidence appeared after the discovery of new documents in the Cairo Geniza. 1 Sefer ha-Ibbur by R’ Abraham bar Hiyyạ edited by Filipowski, London 1851, p. 97 quotes a responsum of R. Hai Gaon dated from 4752 AM = 992 C.E. report- ing this tradition. 2 R. Hai Gaon (939-1038) was the last and the most prolific Gaon. He belonged to the Yeshiva of Pumbedita. -

Scottish Fantasy

JOSHUA BELL BRUCH Scottish Fantasy Academy of St Martin in the Fields Br uc h (1838-1920) SCOTTISH FANTASY FOR VIOLIN AND ORCHESTRA, OP. 46 1 I. Introduction: Grave, Adagio cantabile 2 II. Scherzo: Allegro 3 III. Andante sostenuto 4 IV. Finale: Allegro guerriero VIOLIN CONCERTO NO. 1 IN G MINOR, OP. 26 5 I. Vorspiel: Allegro moderato 6 II. Adagio 7 III. Finale: Allegro energico Joshua Bell, Soloist/Director Academy of St Martin in the Fields Master of More than Melody The works presented here are two out of the three pieces by Max Bruch that can be called staples of the classical repertoire. (The third is his piece for cello and orchestra, Kol Nidrei.) In his lifetime he was best known for large-scale choral works, well received at their premieres and popular with the many amateur choral societies found throughout Europe in the later 19th century. Those choruses began to dwindle once the 20th century got underway. As they disappeared, Bruch’s cantatas and oratorios also faded from consciousness, rarely, if ever, to be heard again. By association, Bruch became thought of as a composer whose time had come and gone. It is interesting to compare the very diff erent assessments of him in two successive editions of Grove’s Dictionary of Music, from 1904 and 1954. The earlier edition declared: “He is above all a master of melody, and of the eff ective treatment of masses of sound.” By 1954 the verdict on his output was dismissive and condescending: ‘It is its lack of adventure that limited its fame.’ Bruch was born during the lifetimes of Mendelssohn and Schumann and died when Schoenberg and Stravinsky were creating gigantic waves in musical life. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Jae Cosmos Lee, Violin

“CELLISSIMO” PROGRAM NOTES By Jae Cosmos Lee, Violin Max Brush (1838 – 1920) At the urging of the beginning with a slow introduction, which is Cello virtuoso Robert Hausmann, the an example of Beethoven breaking off from German Romantic composer, Max Bruch the normal fast movement form, especially completed his op.47, Kol Nidrei (the in the last movement of an instrumental Aramaic phrase, which means All Vows, and work. Moreover, the entire third movement is the incantation that starts the Yom Kippur is in E major, which is the dominant key from service) in 1880 and publishing it a year later the original A major that the first movement in Berlin. Along with his first Violin is written in, which at the time was Concerto, this composition, originally for considered highly unconventional. The A Cello and Orchestra, is one of his most minor Scherzo, which comprises the second beloved and widely performed pieces. For movement, is in the parallel minor to the that reason, it led the German National opening movement's key, which can also be Socialist Party during the 1930's to assume considered Beethoven going against the that Bruch was of Jewish origin and banned grain of his Viennese contemporaries. his music until Germany's defeat in the Second World War. Fortunately, for Bruch, who was raised Protestant, and whose ancestors were not Jewish, his music Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) at age 57, survived the persecution and Kol Nidrei is earnestly contemplated retirement from still firmly planted in the canon of every composing after the premiere of his String cellist. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

The Man-Made Holiday Rabbi Aaron Kraft Wexner Kollel Elyon

The Man-Made Holiday Rabbi Aaron Kraft Wexner Kollel Elyon Purim Then and Now The verses towards the end of Megillat Esther leave us with an ambiguous understanding of Purim’s status. They repeat the general themes and mitzvot of the day numerous times, but with regards to whether Purim is actually a Yom Tov we find ourselves perplexed. The confusion lies in the comparison between the first Purim celebrated by the victorious Jewish nation and the Purim established by Mordechai for the future. After describing the miraculous events of the 13th and 14th of Adar, the Megillah records the reaction of the Jewish people: על כן היהודים הפרזים הישבים בערי -Therefore do the Jews of the villages, that dwell in the un הפרזות עשים את יום ארבעה עשר לחדש walled towns, make the fourteenth day of the month Adar אדר שמחה ומשתה ויום טוב ומשלוח מנות a day of gladness and feasting, and a Yom Tov,, and of איש לרעהו: .sending portions one to another אסתר ט:יט Esther 9:19 Just three verses later, the Megillah reports Mordechai’s enactment of Purim as a day of annual celebration: כימים אשר נחו בהם היהודים The days wherein the Jews had rest from their enemies, and the מאויביהם והחדש אשר נהפך להם ,month which was turned unto them from sorrow to gladness מיגון לשמחה ומאבל ליום טוב לעשות and from mourning into a good day; that they should make אותם ימי משתה ושמחה ומשלוח them days of feasting and gladness, and of sending portions מנות איש לרעהו ומתנות לאביונים: one to another, and gifts to the poor אסתר ט:כב Esther 9:22 In other words, the pesukim deem the initial celebration a Yom Tov whereas Mordechai drops this formulation in his decree for the future. -

Getting Our Heads Around Jewish Prayer

Getting our Heads Around Jewish Prayer HOW DID WE GET HERE? MOVING FROM SACRIFICE TO A SIDDUR The “Jazz” of Worship The Rabbis called this improvisation kavannah, a word we usually translate as inner directedness of the heart, a proper balance, we believe, to the numbed rote that mumbling through the prayer book can become. It’s hard to say exactly when, but liturgy was probably in place, at least in rabbinic circles, by the last century BCE or the first century CE. The “Jazz” of Worship The Rabbis transform private prayer of the moment into a public work like the cult: the honoring of God by the offering of our lips. ◦ First it was set to time. ◦ Second, there were rules about how to do it. And third, each service was structured as to a succession of themes that had to be addressed by the oral interpreters. What the melody line is to jazz, the thematic development is to rabbinic prayer. If improvised wording was kavannah (the “something new” that sages offered when they prayed), the structure of the service was called keva, fixity, predictability, order. Proper prayer combined them both. The case of Rav Ashi and Kedusha Rabbah Pesachim 106a סבר מאי ניהו The Gemara relates that Rav Ashi happened to come to the city of Meḥoza. The Sages of Meḥoza said to קידושא רבה אמר him on Shabbat day: Will the Master recite for us the great kiddush? And they immediately brought him מכדי כל הברכות .a cup of wine כולן בורא פרי Rav Ashi was unsure what they meant by the term great kiddush and wondered if the residents of הגפן אמרי ברישא Meḥoza included other matters in their kiddush.