Clothing Signals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inecxxii, ISSUE XVIII SERVING the COLLEGE of WOOSTER SINCE 1883 Tuesday, February 21, 20O6

The College of Wooster Open Works The oV ice: 2001-2011 "The oV ice" Student Newspaper Collection 2-21-2006 The oW oster Voice (Wooster, OH), 2006-02-21 Wooster Voice Editors Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/voice2001-2011 Recommended Citation Editors, Wooster Voice, "The oosW ter Voice (Wooster, OH), 2006-02-21" (2006). The Voice: 2001-2011. 405. https://openworks.wooster.edu/voice2001-2011/405 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the "The oV ice" Student Newspaper Collection at Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in The oV ice: 2001-2011 by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOL.IneCXXII, ISSUE XVIII SERVING THE COLLEGE OF WOOSTER SINCE 1883 Tuesday, February 21, 20O6 "You can't blame anybody else ... I'm the guy who pulled the trigger and shot my friend. Vice President Dick Cheney in a public comment to Fox News Channel Wooster ; Fees-rise- sUiti Gifts butraoed this Liz Miller Robert Walton said the fee will contin- competitive salaries for faculty and that they paid much, much less ue to rise in 2007-0- 8 "and, most likely as staff members." because the College provided ample Editor-in-Chi- ef with other schools, each year after that." "I think it's ridiculous," said Gillian financial aid to make the cost more com- President R. Stanton Hales sent a let- The comprehensive fee is another Trownson '07. Trownson's aid does not parable to that of other public colleges." Monday, Feb. -

Alt-Nation: Joe Moody, Electric Six and Handsome Pete

Alt-Nation: Joe Moody, Electric Six and Handsome Pete When local studio owner Joe Moody passed away earlier this year it left a gaping wound in the heart of the local music community. Through his Danger Studio, Joe recorded hundreds of aspiring musicians across multiple genres. He gave many artists the opportunity to give voice to their dreams by documenting their work on a recording. In Joe’s honor, a motley collection of Providence metal titans will be reuniting to play together for the first time since 1997. Some of these bands — like Shed — have never done a reunion show! Kilgore Smudge vocalist Jay Berndt was kind enough to take some time to answer a few questions on the show, Kilgore and what he is up to now. Marc Clarkin: Can you talk about Joe Moody’s influence on your music career? Jay Berndt: With all the recording studios I’ve been in, Joe was easily the nicest, sweetest guy to work with. He had this immediate way of putting you at ease. And let’s face it: Musicians can be delicate creatures, especially under the microscope in the studio. When we first recorded our Spill demo with Joe in August 1993, we had never been in a recording studio. The whole recording process can be incredibly intimidating and Joe really helped build all of our confidence as songwriters and musicians. He just made the whole process interesting and fun. We recorded, overdubbed and mixed the 10 songs on Spill in 14 hours, which is just unheard of. It also fostered our love of recording because of that amazing first experience with Joe. -

Places to Go, People To

Hanson mistakenINSIDE EXCLUSIVE:for witches, burned. VerThe Vanderbilt Hustler’s Arts su & Entertainment Magazine s OCTOBER 28—NOVEMBER 3, 2009 VOL. 47, NO. 23 VANDY FALL FASHION We found 10 students who put their own spin on this season’s trends. Check it out when you fl ip to page 9. Cinematic Spark Notes for your reading pleasure on page 4. “I’m a mouse. Duh!” Halloween costume ideas beyond animal ears and hotpants. Turn to page 8 and put down the bunny ears. PLACES TO GO, PEOPLE TO SEE THURSDAY, OCTOBER 29 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 30 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 31 The Regulars The Black Lips – The Mercy Lounge Jimmy Hall and The Prisoners of Love Reunion Show The Avett Brothers – Ryman Auditorium THE RUTLEDGE The Mercy Lounge will play host to self described psychedelic/ There really isn’t enough good to be said about an Avett Brothers concert. – 3rd and Lindsley 410 Fourth Ave. South 37201 comedy band the Black Lips. With heavy punk rock infl uence and Singing dirty blues and southern rock with an earthy, roots The energy, the passion, the excitement, the emotion, the talent … all are 782-6858 mildly witty lyrics, these Lips are not Flaming but will certainly music sound, Jimmy Hall and his crew stick to the basics with completely unrivaled when it comes to the band’s explosive live shows. provide another sort of entertainment. The show will lean towards a songs like “Still Want To Be Your Man.” The no nonsense Whether it’s a heart wrenchingly beautiful ballad or a hard-driving rock punk or skaa atmosphere, though less angry. -

The Guardian, April 2, 2008

Wright State University CORE Scholar The Guardian Student Newspaper Student Activities 4-2-2008 The Guardian, April 2, 2008 Wright State University Student Body Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/guardian Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright State University Student Body (2008). The Guardian, April 2, 2008. : Wright State University. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Activities at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Guardian Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "i:;;Wednescl i.i ·:~ · ' . '~ . , State Vniversi -:Apr .. 2, 2.0Q1.\" \. •• ~· - ..-' L - ~"' .... lN "l ' ... f ' 2- 2008 ~~:::~~~~~~~~~~~~~=:'::~~~~~~~~~~~r.Jml]bart;b SITY'S CAMPUS NEWSPAPER rary 3640 Colonel Glenn Hwy. 014 Student Union, Dayton, OH 45435 Issue No. 21 Vol. 44 A SMA All-American Newspaper 2 ......... .................. IH.~.i:.~.µ~RP.JA.~... 1.. W.~9Q~~.q9.Y.c.A.P.r:.6..... ~99.~.... ................................................................................................................... :···· ...................................................................................................................... .. Editor-in-Chief Inside Nikki Ferrell Managing Editor News Mailinh Nguyen Privacy Rights ........ News Editor 5 Chelsey Levingston Students complain about Assistant News Editor Community Advisors violating Tiffany Johnson privacy rights News Writers Amber Riippa, Adam Feuer. John Sylva Opinion re 6 - Officer were di - Copy Editor March 9 - Offic r were ent to Meadow Run ........8 patched to Fore t Lane on report of a Emily Crawford Dunbar Library on r port of a tudent naked rapid raccoon out id the Student complains about prob threatenin to get a gun during aver building. The raccoon appeared to be ports Editor lems at Meadow Run bal altercation. -

Electric Six Flashy Mp3, Flac, Wma

Electric Six Flashy mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: Flashy Country: US Released: 2008 Style: New Wave, Hard Rock, Rock & Roll MP3 version RAR size: 1724 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1535 mb WMA version RAR size: 1362 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 196 Other Formats: APE AA DXD AUD MOD MP2 MP3 Tracklist Hide Credits Gay Bar Part Two 1 2:42 Trumpet – Kevin Bayson Formula 409 2 3:42 Written-By – Thompson*, Spencer*, Shipps* 3 We Were Witchy Witchy White Women 3:55 4 Dirty Ball 3:39 5 Lovers Beware 3:19 6 Your Heat Is Rising 3:31 7 Face Cuts 3:14 8 Heavy Woman 3:14 9 Flashy Man 2:04 10 Watching Evil Empires Fall Apart 3:58 Graphic Designer 11 4:36 Written-By – Thompson*, Alonso*, Spencer*, Shipps* 12 Transatlantic Flight 4:01 13 Making Progress 2:58 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Metropolis Records Copyright (c) – Metropolis Records Produced At – Hamtramck Sound Machine Mastered At – Precision Mastering Pressed By – Cinram, Olyphant, PA – Z71882 Credits Alto Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone, Baritone Saxophone – Christian Doble Artwork – Ron Zakrin Bass [The Electric Four-string Bass], Clavinet – Smorgasbord Booking [North American] – Dave Kaplan Booking [Worldwide] – Jack Notman Drums, Timbales – Percussion World Guitar, Autoharp – The Colonel Guitar, Synthesizer [Casio Pt-50] – Johnny Na$hinal* Lyrics By – Tyler Spencer Management – Chris Fuller Mastered By – Tom Baker Photography By – Alicia Gbur Producer – Zach Shipps Synthesizer, Other [Bleep Blop] – Tait Nucleus? Tracking By [Drums] – Chris Duross, -

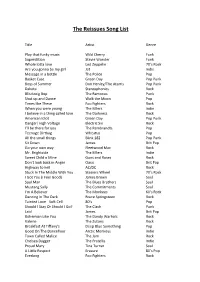

The Reissues Song List

The Reissues Song List Title Artist Genre Play that funky music Wild Cherry Funk Superstition Stevie Wonder Funk Whole lotta love Led Zeppelin 70’s Rock Are you gonna be my girl Jet Indie Message in a bottle The Police Pop Basket Case Green Day Pop Punk Boys of Summer Don Henley/The Atarris Pop Punk Dakota Stereophonics Rock Blitzkreig Bop The Ramones Punk Shut up and Dance Walk the Moon Pop Times like These Foo Fighters Rock When you were young The Killers Indie I believe in a thing called love The Darkness Rock American Idiot Green Day Pop Punk Danger! High Voltage Electric Six Rock I’ll be there for you The Rembrandts Pop Teenage Dirtbag Wheatus Pop All the small things Blink 182 Pop Punk Sit Down James Brit Pop Go your own way Fleetwood Mac Rock Mr. Brightside The Killers Indie Sweet Child o Mine Guns and Roses Rock Don’t look back in Anger Oasis Brit Pop Highway to hell AC/DC Rock Stuck In The Middle With You Stealers Wheel 70’s Rock I Got You (I Feel Good) James Brown Soul Soul Man The Blues Brothers Soul Mustang Sally The Commitments Soul I'm A Believer The Monkees 60’s Rock Dancing In The Dark Bruce Springsteen Rock Tainted Love Soft Cell 80’s Pop Should I Stay Or Should I Go? The Clash Punk Laid James Brit Pop Bohemian Like You The Dandy Warhols Rock Valerie The Zutons Rock Breakfast At Tiffany's Deep Blue Something Pop Good On The Dancefloor Arctic Monkeys Indie Town Called Malice The Jam Rock Chelsea Dagger The Fratellis Indie Proud Mary Tina Turner Soul A Little Respect Erasure 80’s Pop Everlong Foo Fighters Rock Sex On Fire -

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught up in You .38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught Up in You .38 Special Hold On Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down When You're Young 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 30 Seconds to Mars Closer to the Edge 30 Seconds to Mars The Kill 30 Seconds to Mars Kings and Queens 30 Seconds to Mars This is War 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Down 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect The 88 Sons and Daughters a-ha Take on Me Abnormality Visions AC/DC Back in Black (Live) AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) AC/DC Fire Your Guns (Live) AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) (Live) AC/DC Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) AC/DC Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC The Jack (Live) AC/DC Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC T.N.T. (Live) AC/DC Thunderstruck (Live) AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie (Live) AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long (Live) Ace Frehley Outer Space Ace of Base The Sign The Acro-Brats Day Late, Dollar Short The Acro-Brats Hair Trigger Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the Saddle Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream On (Live) Aerosmith Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Eat the Rich Aerosmith I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Janie's Got a Gun Aerosmith Legendary Child Aerosmith Livin' On the Edge Aerosmith Love in an Elevator Aerosmith Lover Alot Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Rats in the Cellar Aerosmith Seasons of Wither Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Train Kept A Rollin' Aerosmith Walk This Way AFI Beautiful Thieves AFI End Transmission AFI Girl's Not Grey AFI The Leaving Song, Pt. -

Explains Why They Did Not Follow the Typical Blueprint for Female Rock Bands. Page 6 Muncie's All-Girl Quartet

72 HOURS OCTOBER 16, 2003 U! ARCMuncie’sA all-girlD quartetE explains why they did not OUR follow the typical blueprint for female rock bands. R page 6 BUTT ON 285-8257 INSIDE: MICHELLE BRANCH, THE MATRIX RELOADED, ELECTRIC SIX, WHITE RIVER LANDING, ENIGMA, THE STROKES, JONATHAN SANDERS’ ‘IN MY HEADPHONES’, 2 FAST 2 FURIOUS, VERTICAL HORIZON 2 • Culture CULTURE EVERYTHING BUT POLE DANCING Vicki Lawrence CMT’s Most Zack Bent: and Mama — A Wanted Live Dropping the Two-Woman with Rascal Ball and Other Show Flats, Chris Common 72HOURS Civic Hall Cagle and Brian Dilemmas Performing Arts McComas Mitchell Place Center Emens Gallery The Ball State Daily News Saturday Auditorium ends October 28 arts and entertainment tab 4 p.m. and 8 Friday Friday and p.m. 8 p.m. Saturday sold out noon to 5:30 Rent p.m. Don’t see your event listed? Clowes Ball State Sunday Memorial Hall Symphony noon to 4 p.m. Friday Orchestra 8 p.m Emens Friday Night Saturday Auditorium Filmworks: 2 p.m. and 8 Sunday Pirates of the p.m. 7:30 p.m. Caribbean Sunday free Pruis Hall 1 p.m. and 6:30 Friday p.m. Heartland Film 9:30 p.m. TELL US! Festival free Of Mice and Indiana History Men Center and What Men Don’t Muncie Civic other Tell phone: 765-285-8257 Theatre Indianapolis Murat Theatre Friday and locations Friday and Saturday Friday, Saturday Saturday 8 p.m. and Sunday 8 p.m. email: [email protected] $7 for students visit www.heart- $26.50 landfilmfesti- val.org for times and locations Movics • 3 BEN ‘MOUSE’ MCSHANE’S CINEMA REEL CALL MOVIES IN THEATERS THIS WEEKEND BLOOD, NINJAS AND UMA OPENING THIS WEEK and his bizarre wins in court, in MUST-SEE MOVIE clan. -

Downbeat.Com February 2011 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 .K. U DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2011 DOWNBEAT BUNKY GREEN & RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA // OMAR SOSA // JOHN MCNEIL // KEVIN EUBANKS // JAZZ VENUE GUIDE FEBRUARY 2011 FEBRUARY 2011 VOLUME 78 – NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser Circulation Assistant Alyssa Beach ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

A Convergencia Dos Videos Musicias Na Web Social.Pdf

Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Comunicação e Arte 2014 JOÃO PEDRO A CONVERGÊNCIA DOS VÍDEOS MUSICAIS NA DA COSTA WEB SOCIAL: CONCEPTUALIZAÇÃO E ANÁLISE Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Comunicação e Arte 2014 JOÃO PEDRO A CONVERGÊNCIA DOS VÍDEOS MUSICAIS NA WEB DA COSTA SOCIAL: CONCEPTUALIZAÇÃO E ANÁLISE Dissertação apresentada à Universidade de Aveiro para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Doutor em Informação e Comunicação em Plataformas Digitais, realizada sob a orientação científica do Prof. Doutor Rui Manuel de Assunção Raposo, Professor Auxiliar do Departamento de Comunicação e Arte da Universidade de Aveiro e da Prof.ª Doutora Rosa Maria Martelo, Professora Associada com Agregação do Departamento de Estudos Portugueses e Estudos Românicos da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto. O projecto de investigação foi financiado por uma bolsa de doutoramento atribuída pela Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (ref. SFRH/BD/68728/2010). o júri presidente Prof.ª Doutora Celeste de Oliveira Alves Coelho professor catedrática da Universidade de Aveiro Prof. Doutor Luís Borges Gouveia professor associado com agregação da Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Fernando Pessoa Prof.ª Doutora Rosa Maria Martelo (co-orientadora) professora associada com agregação da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto Prof. Doutor Armando Malheiro da Silva professor associado da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto Prof. Doutor José Manuel Pereira Azevedo professor associado da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto Prof. Doutor Nelson Troca Zagalo professor auxiliar da Universidade do Minho Prof. Doutor Luís Francisco Mendes Gabriel Pedro professor auxiliar da Universidade de Aveiro Prof. -

Hallo Zusammen

Hallo zusammen, Weihnachten steht vor der Tür! Damit dann auch alles mit den Geschenken klappt, bestellt bitte bis spätestens Freitag, den 12.12.! Bei nachträglich eingehenden Bestellungen können wir keine Gewähr übernehmen, dass die Sachen noch rechtzeitig bis Weihnachten eintrudeln! Vom 24.12. bis einschließlich 5.1.04 bleibt unser Mailorder geschlossen. Ab dem 6.1. sind wir aber wieder für euch da. Und noch eine generelle Anmerkung zum Schluss: Dieser Katalog offeriert nur ein Bruchteil unseres Gesamtangebotes. Falls ihr also etwas im vorliegenden Prospekt nicht findet, schaut einfach unter www.visions.de nach, schreibt ein E-Mail oder ruft kurz an. Viel Spass beim Stöbern wünscht, Udo Boll (VISIONS Mailorder-Boss) NEUERSCHEINUNGEN • CDs VON A-Z • VINYL • CD-ANGEBOTE • MERCHANDISE • BÜCHER • DVDs ! CD-Angebote 8,90 12,90 9,90 9,90 9,90 9,90 12,90 Bad Astronaut Black Rebel Motorcycle Club Cave In Cash, Johnny Cash, Johnny Elbow Jimmy Eat World Acrophobe dto. Antenna American Rec. 2: Unchained American Rec. 3: Solitary Man Cast Of Thousands Bleed American 12,90 7,90 12,90 9,90 12,90 8,90 12,90 Mother Tongue Oasis Queens Of The Stone Age Radiohead Sevendust T(I)NC …Trail Of Dead Ghost Note Be Here Now Rated R Amnesiac Seasons Bigger Cages, Longer Chains Source Tags & Codes 4 Lyn - dto. 10,90 An einem Sonntag im April 10,90 Limp Bizkit - Significant Other 11,90 Plant, Robert - Dreamland 12,90 3 Doors Down - The Better Life 12,90 Element Of Crime - Damals hinterm Mond 10,90 Limp Bizkit - Three Dollar Bill Y’all 8,90 Polyphonic Spree - Absolute Beginner -Bambule 10,90 Element Of Crime - Die schönen Rosen 10,90 Linkin Park - Reanimation 12,90 The Beginning Stages Of 12,90 Aerosmith - Greatest Hits 7,90 Element Of Crime - Live - Secret Samadhi 12,90 Portishead - PNYC 12,90 Aerosmith - Just Push Play 11,90 Freedom, Love & Hapiness 10,90 Live - Throwing Cooper 12,90 Portishead - dto. -

Songs for Thanksgiving 2013

Songs for Thanksgiving 2013 Title Time Artist Album Thank You for the Music 3:51 Abba Abba Come Together 3:44 Aerosmith Armageddon Thank U 4:20 Alanis Morissette iTunes Origi Alanis Moris Thank You 4:18 Alanis Morissette Track Versio March of the Going Home For the First Time 4:43 Alex Wu the Motion P Back to Black 4:00 Amy Winehouse Back to Blac Thank You For Being A Friend 4:43 Andrew Gold Thank You F A Thousand Beautiful Things 3:08 Annie Lennox Bare Thank You (New Orleans Bounce Remix) 3:23 B. Ford Bounce city You To Thank 3:34 Ben Folds Songs for Si Able to Love (Sfaction Mix) 5:28 Benny Benassi & The Biz No Matter W Thankful N' Thoughtful 4:21 Bettye Lavette Thankful N' T I've Got Plenty to Be Thankful For 3:00 Bing Crosby Holiday Inn I Gotta Feeling 4:49 Black Eyed Peas The E.N.D. ( Feast Picking 6:38 Blue Man Group Live at the V I Feel Love 5:14 Blue Man Group & Venus Hum The Comple Turkey Chase 3:30 Bob Dylan Pat Garrett & Give Thanks and Praise 3:15 Bob Marley Confrontatio Thank You for Loving Me 4:37 Bon Jovi Crush Smokin’ 4:21 Boston Boston Thank You 4:35 Boyz II Men 20th Century American Land 4:43 Bruce Springsteen Wrecking Ba 6C6C6CCopyright © 2012 Indoor Cycling Association000000 My Lucky Day 4:00 Bruce Springsteen My Lucky Da Simply Being Loved (Somnambulist) [Junkie XL Simply Being Vocal Mix] 8:58 BT [Remixes] Turkey in the Straw Buck Owens (traditional fo Canadian Bagpipes & the Third Marine Amazing Grace 4:06 Aircraft Wing Band Canadian Ba Thank You Mr DJ 5:04 Carlene Davis Echoes of Lo The Good Life 2:57 Chiddy Bang