The Natural Order of Things: Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Organization Kid

The Atlantic Monthly | April 2001 THE ORGANIZATION KID The young men and women of America's future elite work their laptops to the bone, rarely question authority, and happily accept their positions at the top of the heap as part of the natural order of life BY DAVID BROOKS few months ago I went to Princeton University to see what the young people who are going to be running our country in a few decades are like. Faculty members gave me the names of a few dozen articulate students, and I sent them e-mails, inviting them out to lunch or dinner in small groups. I would go to sleep in my hotel room at around midnight each night, and when I awoke, my mailbox would be full of replies—sent at 1:15 a.m., 2:59 a.m., 3:23 a.m. In our conversations I would ask the students when they got around to sleeping. One senior told me that she went to bed around two and woke up each morning at seven; she could afford that much rest because she had learned to supplement her full day of work by studying in her sleep. As she was falling asleep she would recite a math problem or a paper topic to herself; she would then sometimes dream about it, and when she woke up, the problem might be solved. I asked several students to describe their daily schedules, and their replies sounded like a session of Future Workaholics of America: crew practice at dawn, classes in the morning, resident-adviser duty, lunch, study groups, classes in the afternoon, tutoring disadvantaged kids in Trenton, a cappella practice, dinner, study, science lab, prayer session, hit the StairMaster, study a few hours more. -

30 Rock and Philosophy: We Want to Go to There (The Blackwell

ftoc.indd viii 6/5/10 10:15:56 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY ffirs.indd i 6/5/10 10:15:35 AM The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series Series Editor: William Irwin South Park and Philosophy X-Men and Philosophy Edited by Robert Arp Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski Metallica and Philosophy Edited by William Irwin Terminator and Philosophy Edited by Richard Brown and Family Guy and Philosophy Kevin Decker Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Heroes and Philosophy The Daily Show and Philosophy Edited by David Kyle Johnson Edited by Jason Holt Twilight and Philosophy Lost and Philosophy Edited by Rebecca Housel and Edited by Sharon Kaye J. Jeremy Wisnewski 24 and Philosophy Final Fantasy and Philosophy Edited by Richard Davis, Jennifer Edited by Jason P. Blahuta and Hart Weed, and Ronald Weed Michel S. Beaulieu Battlestar Galactica and Iron Man and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White Edited by Jason T. Eberl Alice in Wonderland and The Offi ce and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Edited by Richard Brian Davis Batman and Philosophy True Blood and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White and Edited by George Dunn and Robert Arp Rebecca Housel House and Philosophy Mad Men and Philosophy Edited by Henry Jacoby Edited by Rod Carveth and Watchman and Philosophy James South Edited by Mark D. White ffirs.indd ii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY WE WANT TO GO TO THERE Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM To pages everywhere . -

Starlog Magazine Issue

'ne Interview Mel 1 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Brooks UGUST INNERSPACE #121 Joe Dante's fantastic voyage with Steven Spielberg 08 John Lithgow Peter Weller '71896H9112 1 ALIENS -v> The Motion Picture GROUP, ! CANNON INC.*sra ,GOLAN-GLOBUS..K?mEDWARO R. PRESSMAN FILM CORPORATION .GARY G0D0ARO™ DOLPH LUNOGREN • PRANK fANGELLA MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE the MOTION ORE ™»COURTENEY COX • JAMES TOIKAN • CHRISTINA PICKLES,* MEG FOSTERS V "SBILL CONTIgS JULIE WEISS Z ANNE V. COATES, ACE. SK RICHARD EDLUND7K WILLIAM STOUT SMNIA BAER B EDWARD R PRESSMAN»™,„ ELLIOT SCHICK -S DAVID ODEll^MENAHEM GOUNJfOMM GLOBUS^TGARY GOODARD *B«xw*H<*-*mm i;-* poiBYsriniol CANNON HJ I COMING TO EARTH THIS AUGUST AUGUST 1987 NUMBER 121 THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE Christopher Reeve—Page 37 beJohn Uthgow—Page 16 Galaxy Rangers—Page 65 MEL BROOKS SPACEBALLS: THE DIRECTOR The master of genre spoofs cant even give the "Star wars" saga an even break Karen Allen—Page 23 Peter weller—Page 45 14 DAVID CERROLD'S GENERATIONS A view from the bridge at those 37 CHRISTOPHER REEVE who serve behind "Star Trek: The THE MAN INSIDE Next Generation" "SUPERMAN IV" 16 ACTING! GENIUS! in this fourth film flight, the Man JOHN LITHGOW! of Steel regains his humanity Planet 10's favorite loony is 45 PETER WELLER just wild about "Harry & the CODENAME: ROBOCOP Hendersons" The "Buckaroo Banzai" star strikes 20 OF SHARKS & "STAR TREK" back as a cyborg centurion in search of heart "Corbomite Maneuver" & a "Colossus" director Joseph 50 TRIBUTE Sargent puts the bite on Remembering Ray Bolger, "Jaws: -

October 2011

The nittany pride Student Newspaper of Penn State New Kensington Vol. VI No. 2 nittanypride.wordpress.com October 2011 Campus Comes To Life! (Photos courtesy Bill Woodard) Student Radio Station Slowly Taking Flight ------------------------------------ Save Your Money, Share Your eTextbooks ------------------------------------ Lady Lions Volleyball Show Significant Progress in 2011 ------------------------------------ Value & Variety at Local Bar Table of ConTenTs Student Radio Station Slowly Taking Flight........................................................ Page 2 THON: For the Kids........................................................................................ Page 3 Profiles in Courage: Mark Messina.................................................................... Page 4 Festival Spirits Not Dampened......................................................................... Pages 5-6 Value and Variety at Local Bar.......................................................................... Pages 7-8 PSNK Soccer Player Helps Team Reach Playoffs.................................................. Page 8 Save Your Money, Share Your eTextbooks.......................................................... Pages 9-10 CAB: We Plan Fun!......................................................................................... Page 10 Sportelli Twins Take Control of Destiny & Play Ball.............................................. Pages 11-12 Top 10 Horror Films of All Time....................................................................... -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY Portrayal of African Americans in the Media

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature Portrayal of African Americans in the Media Master‟s Diploma Thesis Brno 2014 Supervisor: Author: Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. Bc. Lucie Pernicová Declaration I hereby declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. ........................................................ Bc. Lucie Pernicová Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. Zdeněk Janík, M.A., Ph.D. for the patient guidance and valuable advice he provided me with during the writing of this thesis. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 5 2. Portrayal of African Americans in Films and on Television ..................................... 8 2.1. Stereotypical Images and Their Power .............................................................. 8 2.2. Basic Stereotypical Images of African Americans ............................................ 9 2.3. Stereotypical Film Portrayals of African Americans and the Arrival of the Talking Era .................................................................................................................. 12 2.4. Television Portrayals of African Americans .................................................... 14 2.4.1. The Increasing Importance of African American Viewers ....................... 17 2.4.2. Contemporary Images of African Americans .......................................... -

Media Culture: Cultural Studies, Identity and Politics Between The

Media Culture Media Culture develops methods and analyses of contemporary film, television, music, and other artifacts to discern their nature and effects. The book argues that media culture is now the dominant form of culture which socializes us and provides materials for identity in terms of both social reproduction and change. Through studies of Reagan and Rambo, horror films and youth films, rap music and African- American culture, Madonna, fashion, television news and entertainment, MTV, Beavis and Butt-Head, the Gulf War as cultural text, cyberpunk fiction and postmodern theory, Kellner provides a series of lively studies that both illuminate contemporary culture and provide methods of analysis and critique. Many people today talk about cultural studies, but Kellner actually does it, carrying through a unique mixture of theoretical analysis and concrete discussions of some of the most popular and influential forms of contemporary media culture. Criticizing social context, political struggle, and the system of cultural production, Kellner develops a multidimensional approach to cultural studies that broadens the field and opens it to a variety of disciplines. He also provides new approaches to the vexed question of the effects of culture and offers new perspectives for cultural studies. Anyone interested in the nature and effects of contemporary society and culture should read this book. Kellner argues that we are in a state of transition between the modern era and a new postmodern era and that media culture offers a privileged field of study and one that is vital if we are to grasp the full import of the changes currently shaking us. -

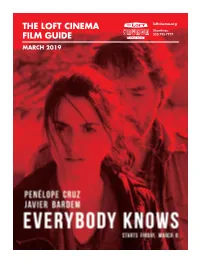

The Loft Cinema Film Guide

loftcinema.org THE LOFT CINEMA Showtimes: FILM GUIDE 520-795-7777 MARCH 2019 WWW.LOFTCINEMA.ORG See what films are playing next, buy tickets, look up showtimes & much more! ENJOY BEER & WINE AT THE LOFT CINEMA! We also offer Fresco Pizza*, Tucson Tamale Company Tamales, Burritos from Tumerico, Ethiopian Wraps from MARCH 2019 Cafe Desta and Sandwiches from the 4th Ave. Deli, along with organic popcorn, craft chocolate bars, vegan SPECIAL ENGAGEMENTS 5-19 cookies and more! *Pizza served after 5pm daily. ESSENTIAL CINEMA 5, 14 LOFT MEMBERSHIPS 7 LOFT JR. 11 BEER OF THE MONTH: SOLAR CINEMA 14, 23, 28 HONEY HIPS STRONG BLONDE ALE JOURNALISM ON SCREEN 17 LATITUDE 33° BREWING COMPANY SCIENCE ON SCREEN 20 ONLY $3.50 ALL THROUGH MARCH! LOFT STAFF SELECTS 21 MONTHLY SERIES 24-25 CLOSED CAPTIONS & AUDIO DESCRIPTIONS! COMMUNITY RENTALS 32-34 The Loft Cinema offers Closed Captions and Audio NEW FILMS 35-45 Descriptions for films whenever they are available. Check our REEL READS SELECTION 43 website to see which films offer this technology. MONDO MONDAYS 46 CULT CLASSICS 47 FILM GUIDES ARE AVAILABLE AT: FREE MEMBERS SCREENING • 1702 Craft Beer & • Epic Cafe • R-Galaxy Pizza THE WEDDING GUEST • Ermanos • Raging Sage (SEE PAGE 44) • aLoft Hotel • Fantasy Comics • Rocco’s Little FRIDAY, MARCH 29, 7:00PM • Antigone Books • First American Title Chicago • Aqua Vita • Frominos • SW University of • Black Crown Visual Arts REGULAR ADMISSION PRICES • Heroes & Villains Coffee • Shot in the Dark $9.75 - Adult | $7.25 - Matinee* • Hotel Congress $8.00 - Student, -

EQUITY News JULY/AUGUST 2010

JULY/AUGUST “The stage is not merely 2010 the meeting place of Volume 95 Number 6 all the arts, but is also the return of art to life.” EQUITYNEWS — OscarWilde A Publication of Actors’ Equity Association • NEWS FOR THE THEATRE PROFESSIONAL • www.actorsequity.org • Periodicals Postage Paid at New York, NY and Additional Mailing Offices California Assembly Equity’s New Home in Chicago Committee Votes “Yes” Prepares for Grand Opening for Single Payer Plan By Pam Spitzner and building management. being “punched” into the Member Services • The second floor will be building to admit more natural n June 29, 2010 by a once again go to the Governor Coordinator, Central Region rented out in its entirety to one light, and an exciting “super majority” vote, for signature. Stay tuned. or more occupants “to be architectural feature will be “Have you moved yet?” the 19-member Earlier in the month, the named later.” multiple skylights and a “light O That’s the question Chicago California Assembly Health Western Regional Board heard • The third floor will be shaft” between the third and Equity members keep asking Committee delivered 13 “Yes” an extensive report, including an Equity’s public area, with fourth floors. Furniture from the the Central Regional staff, as votes versus six “No” votes to in-depth PowerPoint Reception, Membership and current office will be re-used excitement about our new home pass Senator Mark Leno’s presentation created by Jennie with some new additions and in Chicago continues to build. Member Services offices, and Senate Bill 810. The full passage Ford, from members of the meeting rooms. -

La Cinta Blanca Jeff Bridges La Isla Siniestra

+ ¿Adiós a Daney? CINE LA CINTA BLANCA JEFF BRIDGES LA ISLA SINIESTRA . .•. .•. :.. DEL 7 AL 18 DE ABRIL I 2010 - - BUENOS AIRES FESTIVAL INTERNACIONAL DE 12 CINE INDEPENDIENTE • ClnE!COLOr ABASTO ArGEnTinA <~~~;:n~ Buenos Aires haciendo Gobierno de la Ciudad H buenos aires ELAMANTE CINE N°215 ABRIL 2010 SUMARIO Estrenos ara decirlo sin vueltas, éste es uno de esos números que sólo El Amante 2 Loco corazón puede ofrecer. Ajá, dirán, otra vez el autobombo. Pero, realmente, éconocen 4 Gran perfil Jeff Bridges 15 La cinta blanca otra revista que pueda ofrecer análisis detallados de la última película de P 20 Polémica: La isla siniestra Haneke, y también un extenso perfil-celebración colectivo sobre un actor como Jeff 23 El padre de mis hijos Bridges, y también polemizar sobre Scorsese, a la vez que se acerca con humor y eru- 24 Cómo entrenar a tu dragón dición a Mario Bava, y surfea desde Mia Hansen-Leve a Sábato sin descuidar a un dra- 25 Ernesto Sábato, mi padre gón de Dreamworks que parece un gato? ¿Que además pueda ofrecerles una entrevis- 26 Un fueguito. La historia de César ta con Hugo Porta sobre rugby, política y cine, y que a unas pocas páginas celebra a Milstein 27 Polémica: El pescador y su mujer Drew Barrymore con pasión y sentido crítico, y que pueda comparar Música y lágri- 28 La muestra, Un sueño posible mas con El silencio de Lorna? ¿Que cubra festivales de toda clase, que escriba sobre 29 Están todos bien, El libro de los el Bafici y el Abasto, que sea un lugar para cartas polémicas y polémicas internas con secretos, La mosca en la ceniza tanta libertad? 30 Fama, Mongol, Hermanos Y, como si todo esto fuera poco, que con frecuencia pueda reflexionar sobre 31 Los últimos días de Emma Blank, Número 9, Paco su actividad, la crítica, con renovadas energías; que pueda exhibir tal manejo 32 Amante accidental, Sólo para parejas, del tema sin perder frescura para abordarlo desde nuevos ángulos. -

Horror Begins at Home: Family Trauma In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank HORROR BEGINS AT HOME: FAMILY TRAUMA IN PARANORMAL REALITY TV by ANDREW J. BEARD A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2012 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Andrew J. Beard Title: Horror Begins at Home: Family Trauma in Paranormal Reality TV This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of English by: Dr. Carol Stabile Chairperson Dr. Anne Laskaya Member Dr. Priscilla Ovalle Member Dr. Lynn Fujiwara Outside Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2012 ii © 2012 Andrew J. Beard iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Andrew J. Beard Doctor of Philosophy Department of English June 2012 Title: Horror Begins at Home: Family Trauma in Paranormal Reality TV This dissertation argues that paranormal reality television is a form of what some have referred to as “trauma television,” a site of struggle between meanings of family and the violence often found in the hegemonic nuclear family ideal. Programs such as A Haunting and Paranormal State articulate family violence and trauma through a paranormal presence in the heteronormative family home, working to make strange and unfamiliar the domestic and familial milieus in which their episodes take place. -

THE Man Exposes Self to ND Student Jogging On

~~~ -- ------ ~-~---------- -- ~- Get in line Sports recruiting ."·icary mouies raked in the lop box ojflce sales Membership in the MIAA has giuen Saint Thursday this week . .'-iixth ."iense lead the pack. wilh Mary's College an aduantage in recruiting other horror .flicks following. athletes. SEPTEMBER 2, page 13 page 6 1999 THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's VOL XXXIII NO.8 • HTTP://OBSERVER.N D.EDU MAY THE BEST MAN WIN Sweatshop task force visits site rights at f'actoril~s that produce whether there is a way to By MAGGY TINUCCI Notre Dame-liennsed produets. include non-governmental News Writer One responsibility of' tlw task organizations (NGOs) into our f(m:e was to set up a monitor group as a possibl1~ rc~com Five members of Notre ing system for Notre Dame's mendation to Fatlwr Malloy," Damn's Anti-sweatshop Task liecnsos, in order to "put some ffoye said. Foree visitnd El Salvador this ~teeth" into the eode of eon- Tlu~ group did not tour any summer in an ef'f'ort to gain duet, aeeording to Maria factory wlwre Notre IJamn first-hand knowledge about Cannalis, pn~sident of' tho apparel is mad11 and wen• sweatshops. Graduate Student Union. barred entry f'rom the f'rnl) "Wn wont to get a better Since Mar('.h, trade zone in San Salvador, handle on the conditions in thn l'rie()waterhouseCoopers has wlwrn tlw main abusns oc·.cur, factories. It's important for servnd as the sole monitor for according to Cannalis. They nwmbnrs ol' tlw Task Force to th() University. -

I Think We're Alone Now in 150 Words Or Less Subscribe to MNPP!

my new plaid pants: I Think We're Alone Now in 150 Words or Less Page 1 of 28 Share Report Abuse Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In my new plaid pants WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 2010 I Think We're Alone Now in 150 Words or Less . Must be seen, and then rewound and seen immediately again, to be believed... and then you might still not want to believe it, because it's just so JA disconcerting and scary. And funny! NYC, NY These folks are like bright little balls of crazy quotable Tiffany-worshiping magic. Yes, this is the doc that follows My MySpace and/or My the two stalker-types still obsessed with Facebook and/or My Twitter that 80s pop sensation. And it's as uncomfortable and hysterical as View my complete profile you could ever imagine such a thing to be. If you could imagine such things, which beforehand you probably couldn't. Truth isn't just stranger than fiction - truth eats fiction for breakfast sometimes, and then sits in the dark sipping vodka and screaming songstress-themed obscenities. Magical wonderment, fun for the whole family. Subscribe to MNPP! http://mynewplaidpants.blogspot.com/2010/09/i -think -were -alone -now -in -150 -words -or.ht ... 9/28/2010 my new plaid pants: I Think We're Alone Now in 150 Words or Less Page 2 of 28 . MNPP Multiples . Who? JA When? 10:56 AM Labels: 150 or Less , reviews 3 Say What?: Scott said... i've heard about this! and wouldn't ya know it? it's on netflix on demand! someone upstairs loves us! they should tour malls with this movie! 11:54 AM JA said..