Dimension of Space–Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson 3: Rectangles Inscribed in Circles

NYS COMMON CORE MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM Lesson 3 M5 GEOMETRY Lesson 3: Rectangles Inscribed in Circles Student Outcomes . Inscribe a rectangle in a circle. Understand the symmetries of inscribed rectangles across a diameter. Lesson Notes Have students use a compass and straightedge to locate the center of the circle provided. If necessary, remind students of their work in Module 1 on constructing a perpendicular to a segment and of their work in Lesson 1 in this module on Thales’ theorem. Standards addressed with this lesson are G-C.A.2 and G-C.A.3. Students should be made aware that figures are not drawn to scale. Classwork Scaffolding: Opening Exercise (9 minutes) Display steps to construct a perpendicular line at a point. Students follow the steps provided and use a compass and straightedge to find the center of a circle. This exercise reminds students about constructions previously . Draw a segment through the studied that are needed in this lesson and later in this module. point, and, using a compass, mark a point equidistant on Opening Exercise each side of the point. Using only a compass and straightedge, find the location of the center of the circle below. Label the endpoints of the Follow the steps provided. segment 퐴 and 퐵. Draw chord 푨푩̅̅̅̅. Draw circle 퐴 with center 퐴 . Construct a chord perpendicular to 푨푩̅̅̅̅ at and radius ̅퐴퐵̅̅̅. endpoint 푩. Draw circle 퐵 with center 퐵 . Mark the point of intersection of the perpendicular chord and the circle as point and radius ̅퐵퐴̅̅̅. 푪. Label the points of intersection . -

Squaring the Circle a Case Study in the History of Mathematics the Problem

Squaring the Circle A Case Study in the History of Mathematics The Problem Using only a compass and straightedge, construct for any given circle, a square with the same area as the circle. The general problem of constructing a square with the same area as a given figure is known as the Quadrature of that figure. So, we seek a quadrature of the circle. The Answer It has been known since 1822 that the quadrature of a circle with straightedge and compass is impossible. Notes: First of all we are not saying that a square of equal area does not exist. If the circle has area A, then a square with side √A clearly has the same area. Secondly, we are not saying that a quadrature of a circle is impossible, since it is possible, but not under the restriction of using only a straightedge and compass. Precursors It has been written, in many places, that the quadrature problem appears in one of the earliest extant mathematical sources, the Rhind Papyrus (~ 1650 B.C.). This is not really an accurate statement. If one means by the “quadrature of the circle” simply a quadrature by any means, then one is just asking for the determination of the area of a circle. This problem does appear in the Rhind Papyrus, but I consider it as just a precursor to the construction problem we are examining. The Rhind Papyrus The papyrus was found in Thebes (Luxor) in the ruins of a small building near the Ramesseum.1 It was purchased in 1858 in Egypt by the Scottish Egyptologist A. -

Hausdorff Dimension of Singular Vectors

HAUSDORFF DIMENSION OF SINGULAR VECTORS YITWAH CHEUNG AND NICOLAS CHEVALLIER Abstract. We prove that the set of singular vectors in Rd; d ≥ 2; has Hausdorff dimension d2 d d+1 and that the Hausdorff dimension of the set of "-Dirichlet improvable vectors in R d2 d is roughly d+1 plus a power of " between 2 and d. As a corollary, the set of divergent t t −dt trajectories of the flow by diag(e ; : : : ; e ; e ) acting on SLd+1 R= SLd+1 Z has Hausdorff d codimension d+1 . These results extend the work of the first author in [6]. 1. Introduction Singular vectors were introduced by Khintchine in the twenties (see [14]). Recall that d x = (x1; :::; xd) 2 R is singular if for every " > 0, there exists T0 such that for all T > T0 the system of inequalities " (1.1) max jqxi − pij < and 0 < q < T 1≤i≤d T 1=d admits an integer solution (p; q) 2 Zd × Z. In dimension one, only the rational numbers are singular. The existence of singular vectors that do not lie in a rational subspace was proved by Khintchine for all dimensions ≥ 2. Singular vectors exhibit phenomena that cannot occur in dimension one. For instance, when x 2 Rd is singular, the sequence 0; x; 2x; :::; nx; ::: fills the torus Td = Rd=Zd in such a way that there exists a point y whose distance in the torus to the set f0; x; :::; nxg, times n1=d, goes to infinity when n goes to infinity (see [4], chapter V). -

THE DIMENSION of a VECTOR SPACE 1. Introduction This Handout

THE DIMENSION OF A VECTOR SPACE KEITH CONRAD 1. Introduction This handout is a supplementary discussion leading up to the definition of dimension of a vector space and some of its properties. We start by defining the span of a finite set of vectors and linear independence of a finite set of vectors, which are combined to define the all-important concept of a basis. Definition 1.1. Let V be a vector space over a field F . For any finite subset fv1; : : : ; vng of V , its span is the set of all of its linear combinations: Span(v1; : : : ; vn) = fc1v1 + ··· + cnvn : ci 2 F g: Example 1.2. In F 3, Span((1; 0; 0); (0; 1; 0)) is the xy-plane in F 3. Example 1.3. If v is a single vector in V then Span(v) = fcv : c 2 F g = F v is the set of scalar multiples of v, which for nonzero v should be thought of geometrically as a line (through the origin, since it includes 0 · v = 0). Since sums of linear combinations are linear combinations and the scalar multiple of a linear combination is a linear combination, Span(v1; : : : ; vn) is a subspace of V . It may not be all of V , of course. Definition 1.4. If fv1; : : : ; vng satisfies Span(fv1; : : : ; vng) = V , that is, if every vector in V is a linear combination from fv1; : : : ; vng, then we say this set spans V or it is a spanning set for V . Example 1.5. In F 2, the set f(1; 0); (0; 1); (1; 1)g is a spanning set of F 2. -

MTH 304: General Topology Semester 2, 2017-2018

MTH 304: General Topology Semester 2, 2017-2018 Dr. Prahlad Vaidyanathan Contents I. Continuous Functions3 1. First Definitions................................3 2. Open Sets...................................4 3. Continuity by Open Sets...........................6 II. Topological Spaces8 1. Definition and Examples...........................8 2. Metric Spaces................................. 11 3. Basis for a topology.............................. 16 4. The Product Topology on X × Y ...................... 18 Q 5. The Product Topology on Xα ....................... 20 6. Closed Sets.................................. 22 7. Continuous Functions............................. 27 8. The Quotient Topology............................ 30 III.Properties of Topological Spaces 36 1. The Hausdorff property............................ 36 2. Connectedness................................. 37 3. Path Connectedness............................. 41 4. Local Connectedness............................. 44 5. Compactness................................. 46 6. Compact Subsets of Rn ............................ 50 7. Continuous Functions on Compact Sets................... 52 8. Compactness in Metric Spaces........................ 56 9. Local Compactness.............................. 59 IV.Separation Axioms 62 1. Regular Spaces................................ 62 2. Normal Spaces................................ 64 3. Tietze's extension Theorem......................... 67 4. Urysohn Metrization Theorem........................ 71 5. Imbedding of Manifolds.......................... -

23. Dimension Dimension Is Intuitively Obvious but Surprisingly Hard to Define Rigorously and to Work With

58 RICHARD BORCHERDS 23. Dimension Dimension is intuitively obvious but surprisingly hard to define rigorously and to work with. There are several different concepts of dimension • It was at first assumed that the dimension was the number or parameters something depended on. This fell apart when Cantor showed that there is a bijective map from R ! R2. The Peano curve is a continuous surjective map from R ! R2. • The Lebesgue covering dimension: a space has Lebesgue covering dimension at most n if every open cover has a refinement such that each point is in at most n + 1 sets. This does not work well for the spectrums of rings. Example: dimension 2 (DIAGRAM) no point in more than 3 sets. Not trivial to prove that n-dim space has dimension n. No good for commutative algebra as A1 has infinite Lebesgue covering dimension, as any finite number of non-empty open sets intersect. • The "classical" definition. Definition 23.1. (Brouwer, Menger, Urysohn) A topological space has dimension ≤ n (n ≥ −1) if all points have arbitrarily small neighborhoods with boundary of dimension < n. The empty set is the only space of dimension −1. This definition is mostly used for separable metric spaces. Rather amazingly it also works for the spectra of Noetherian rings, which are about as far as one can get from separable metric spaces. • Definition 23.2. The Krull dimension of a topological space is the supre- mum of the numbers n for which there is a chain Z0 ⊂ Z1 ⊂ ::: ⊂ Zn of n + 1 irreducible subsets. DIAGRAM pt ⊂ curve ⊂ A2 For Noetherian topological spaces the Krull dimension is the same as the Menger definition, but for non-Noetherian spaces it behaves badly. -

PSY 4960/5960 Science Vs. Pseudoscience Human Life

PSY 4960/5960 Science vs. Pseudoscience •What is science? Human Life Expectancy Why has the average human lifespan doubled over the past 200 years? 1 Quick Quiz • True or false? • Most people use only about 10% of their brain capacity • Drinking coffee is a good way to sober up after heavy drinking • Hypnosis can help us to recall things we’ve forgotten • If you’re unsure of your answer while taking a test, it’s best to stick with your initial answer Common Sense? •Look before you leap. •He who hesitates is lost. •Birds of a feather flock together. •Opposites attract. •Absence makes the heart grow fonder. •Out of sight, out of mind. • •Better safe than sorry. •Nothing ventured, nothing gained. •Two heads are better than one. •Too many cooks spoil the bthbroth. •The bigger the better. •Good things come in small packages. •Actions speak louder than words. •The pen is mightier than the sword. •Clothes make the man. •Don’t judge a book by its cover. •The more the merrier. •Two’s company, three’s a crowd. •You’re never too old to learn. •You can’t teach an old dog new tricks. Lilienfeld et al. (2007) Operational Definition • Science is – “A set of methods designed to describe and interpret observed or inferred phenomena, past or pp,resent, and aimed at building a testable body of knowledge open to rejection or confirmation.” – A toolbox of skills designed to prevent us from fooling ourselves – Learning to minimize your thinking errors – Self‐correcting Shermer (2002) 2 What Makes a Good Scientist? • Communalism –a willingness to share data • Disinterestedness –trying not to be influenced by personal or financial investments • A tiny voice saying “I might be wrong” • “Utter honesty –a kind of leaning over Merton (1942) backwards” Sagan (1995) Feynman (1988) Quick Quiz Write down the names of as many living scientists as you can, including their fields. -

General Topology

General Topology Tom Leinster 2014{15 Contents A Topological spaces2 A1 Review of metric spaces.......................2 A2 The definition of topological space.................8 A3 Metrics versus topologies....................... 13 A4 Continuous maps........................... 17 A5 When are two spaces homeomorphic?................ 22 A6 Topological properties........................ 26 A7 Bases................................. 28 A8 Closure and interior......................... 31 A9 Subspaces (new spaces from old, 1)................. 35 A10 Products (new spaces from old, 2)................. 39 A11 Quotients (new spaces from old, 3)................. 43 A12 Review of ChapterA......................... 48 B Compactness 51 B1 The definition of compactness.................... 51 B2 Closed bounded intervals are compact............... 55 B3 Compactness and subspaces..................... 56 B4 Compactness and products..................... 58 B5 The compact subsets of Rn ..................... 59 B6 Compactness and quotients (and images)............. 61 B7 Compact metric spaces........................ 64 C Connectedness 68 C1 The definition of connectedness................... 68 C2 Connected subsets of the real line.................. 72 C3 Path-connectedness.......................... 76 C4 Connected-components and path-components........... 80 1 Chapter A Topological spaces A1 Review of metric spaces For the lecture of Thursday, 18 September 2014 Almost everything in this section should have been covered in Honours Analysis, with the possible exception of some of the examples. For that reason, this lecture is longer than usual. Definition A1.1 Let X be a set. A metric on X is a function d: X × X ! [0; 1) with the following three properties: • d(x; y) = 0 () x = y, for x; y 2 X; • d(x; y) + d(y; z) ≥ d(x; z) for all x; y; z 2 X (triangle inequality); • d(x; y) = d(y; x) for all x; y 2 X (symmetry). -

Geometry Course Outline

GEOMETRY COURSE OUTLINE Content Area Formative Assessment # of Lessons Days G0 INTRO AND CONSTRUCTION 12 G-CO Congruence 12, 13 G1 BASIC DEFINITIONS AND RIGID MOTION Representing and 20 G-CO Congruence 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Combining Transformations Analyzing Congruency Proofs G2 GEOMETRIC RELATIONSHIPS AND PROPERTIES Evaluating Statements 15 G-CO Congruence 9, 10, 11 About Length and Area G-C Circles 3 Inscribing and Circumscribing Right Triangles G3 SIMILARITY Geometry Problems: 20 G-SRT Similarity, Right Triangles, and Trigonometry 1, 2, 3, Circles and Triangles 4, 5 Proofs of the Pythagorean Theorem M1 GEOMETRIC MODELING 1 Solving Geometry 7 G-MG Modeling with Geometry 1, 2, 3 Problems: Floodlights G4 COORDINATE GEOMETRY Finding Equations of 15 G-GPE Expressing Geometric Properties with Equations 4, 5, Parallel and 6, 7 Perpendicular Lines G5 CIRCLES AND CONICS Equations of Circles 1 15 G-C Circles 1, 2, 5 Equations of Circles 2 G-GPE Expressing Geometric Properties with Equations 1, 2 Sectors of Circles G6 GEOMETRIC MEASUREMENTS AND DIMENSIONS Evaluating Statements 15 G-GMD 1, 3, 4 About Enlargements (2D & 3D) 2D Representations of 3D Objects G7 TRIONOMETRIC RATIOS Calculating Volumes of 15 G-SRT Similarity, Right Triangles, and Trigonometry 6, 7, 8 Compound Objects M2 GEOMETRIC MODELING 2 Modeling: Rolling Cups 10 G-MG Modeling with Geometry 1, 2, 3 TOTAL: 144 HIGH SCHOOL OVERVIEW Algebra 1 Geometry Algebra 2 A0 Introduction G0 Introduction and A0 Introduction Construction A1 Modeling With Functions G1 Basic Definitions and Rigid -

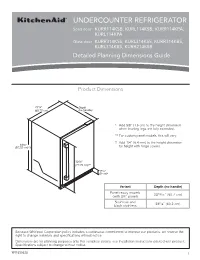

Dimension Guide

UNDERCOUNTER REFRIGERATOR Solid door KURR114KSB, KURL114KSB, KURR114KPA, KURL114KPA Glass door KURR314KSS, KURL314KSS, KURR314KBS, KURL314KBS, KURR214KSB Detailed Planning Dimensions Guide Product Dimensions 237/8” Depth (60.72 cm) (no handle) * Add 5/8” (1.6 cm) to the height dimension when leveling legs are fully extended. ** For custom panel models, this will vary. † Add 1/4” (6.4 mm) to the height dimension 343/8” (87.32 cm)*† for height with hinge covers. 305/8” (77.75 cm)** 39/16” (9 cm)* Variant Depth (no handle) Panel ready models 2313/16” (60.7 cm) (with 3/4” panel) Stainless and 235/8” (60.2 cm) black stainless Because Whirlpool Corporation policy includes a continuous commitment to improve our products, we reserve the right to change materials and specifications without notice. Dimensions are for planning purposes only. For complete details, see Installation Instructions packed with product. Specifications subject to change without notice. W11530525 1 Panel ready models Stainless and black Dimension Description (with 3/4” panel) stainless models A Width of door 233/4” (60.3 cm) 233/4” (60.3 cm) B Width of the grille 2313/16” (60.5 cm) 2313/16” (60.5 cm) C Height to top of handle ** 311/8” (78.85 cm) Width from side of refrigerator to 1 D handle – door open 90° ** 2 /3” (5.95 cm) E Depth without door 2111/16” (55.1 cm) 2111/16” (55.1 cm) F Depth with door 2313/16” (60.7 cm) 235/8” (60.2 cm) 7 G Depth with handle ** 26 /16” (67.15 cm) H Depth with door open 90° 4715/16” (121.8 cm) 4715/16” (121.8 cm) **For custom panel models, this will vary. -

Spectral Dimensions and Dimension Spectra of Quantum Spacetimes

PHYSICAL REVIEW D 102, 086003 (2020) Spectral dimensions and dimension spectra of quantum spacetimes † Michał Eckstein 1,2,* and Tomasz Trześniewski 3,2, 1Institute of Theoretical Physics and Astrophysics, National Quantum Information Centre, Faculty of Mathematics, Physics and Informatics, University of Gdańsk, ulica Wita Stwosza 57, 80-308 Gdańsk, Poland 2Copernicus Center for Interdisciplinary Studies, ulica Szczepańska 1/5, 31-011 Kraków, Poland 3Institute of Theoretical Physics, Jagiellonian University, ulica S. Łojasiewicza 11, 30-348 Kraków, Poland (Received 11 June 2020; accepted 3 September 2020; published 5 October 2020) Different approaches to quantum gravity generally predict that the dimension of spacetime at the fundamental level is not 4. The principal tool to measure how the dimension changes between the IR and UV scales of the theory is the spectral dimension. On the other hand, the noncommutative-geometric perspective suggests that quantum spacetimes ought to be characterized by a discrete complex set—the dimension spectrum. We show that these two notions complement each other and the dimension spectrum is very useful in unraveling the UV behavior of the spectral dimension. We perform an extended analysis highlighting the trouble spots and illustrate the general results with two concrete examples: the quantum sphere and the κ-Minkowski spacetime, for a few different Laplacians. In particular, we find that the spectral dimensions of the former exhibit log-periodic oscillations, the amplitude of which decays rapidly as the deformation parameter tends to the classical value. In contrast, no such oscillations occur for either of the three considered Laplacians on the κ-Minkowski spacetime. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevD.102.086003 I. -

Find the Radius Or Diameter of the Circle with the Given Dimensions. 2

8-1 Circumference Find the radius or diameter of the circle with the given dimensions. 2. d = 24 ft SOLUTION: The radius is 12 feet. ANSWER: 12 ft Find the circumference of the circle. Use 3.14 or for π. Round to the nearest tenth if necessary. 4. SOLUTION: The circumference of the circle is about 25.1 feet. ANSWER: 3.14 × 8 = 25.1 ft eSolutions Manual - Powered by Cognero Page 1 8-1 Circumference 6. SOLUTION: The circumference of the circle is about 22 miles. ANSWER: 8. The Belknap shield volcano is located in the Cascade Range in Oregon. The volcano is circular and has a diameter of 5 miles. What is the circumference of this volcano to the nearest tenth? SOLUTION: The circumference of the volcano is about 15.7 miles. ANSWER: 15.7 mi eSolutions Manual - Powered by Cognero Page 2 8-1 Circumference Copy and Solve Show your work on a separate piece of paper. Find the diameter given the circumference of the object. Use 3.14 for π. 10. a satellite dish with a circumference of 957.7 meters SOLUTION: The diameter of the satellite dish is 305 meters. ANSWER: 305 m 12. a nickel with a circumference of about 65.94 millimeters SOLUTION: The diameter of the nickel is 21 millimeters. ANSWER: 21 mm eSolutions Manual - Powered by Cognero Page 3 8-1 Circumference Find the distance around the figure. Use 3.14 for π. 14. SOLUTION: The distance around the figure is 5 + 5 or 10 feet plus of the circumference of a circle with a radius of 5 feet.