Gresham College 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senior Textile Artist Badge Workshop

Senior Textile Artist Badge Workshop An At-Home Program GSCCC Senior Textile Artist Badge Workshop (At-Home) • When you see fabrics, yarn, or string off all colors and textures what do you think of? Do you envision all of the things you could create? Let’s turn those visions into reality! Program Outline Materials: - Computer - Internet access - Materials for craft of choice Step 1: Choose your textile art There are a number of textile arts in the world from macramé to crocheting to quilting and much more. In this step you will be doing some research to learn about a textile art that you find interesting and that you would like to learn. Some of the most common textile arts are macramé, embroidery, cross-stitch, needlework, knitting, crocheting, weaving, and quilting. Do some research to find out about these or other textile arts. Below are some helpful links to start with. Here are a few links to get your search started – crochet, macramé, embroidery, weaving. Click here to see what some current textile artists are doing. Step 2: Find your tools and materials Now that you have chosen your art, you need to gather materials. Crocheting needs crochet hooks and yarn. Embroidery needs needles, embroidery floss, hoops, and fabric. Do some research about what you will need for your chosen textile art form. What all is involved? Do you know anyone who already has the supplies? Would they be willing to lend you some materials? Below are some great resources to learn about materials needed for the most common textile arts. -

'L::C Make a Gathered Skirt

H7l.f -·'1~ 'l::c Make A Gathered Skirt CIRCULAR 580 OCTOBER 1964 AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION SERVICE VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE BLACKSBURG, VIRGINIA Make a Gathered Skirt Prepared by MarrJaret Groseclose, Err:tension ClothinrJ Specialist •Many girls like gathered skirts and they Make a Placket • are easy to make. Plump girls look best in 1. Work with the side seam where the gored skirts. When you make a gathered opening was left for the placket. skirt, you learn to make seams, put in a 2. Fold back the front placket extension placket, fit a waistband, hem a skirt, and put to the seam line. Press and pin. on a fastener. You study what to look for in 3. Machine stitch the length of the placket choosing a fabric and how to prepare it for opening 5/ 8" from the folded edge. Stitch cutting a garment. This will help you in diagonally to the folded edge (or seam line), making other garments. catching the back extension. 4. Clip the back seam allowance almost Supplies You Will Need to the stitching line, approximately 1/2" be- low the end of the placket. Include a sewing box, thread to match 5. Press the side seams open. background of fabric, hooks and straight eyes, 6. Two snap fasteners may be used to i:maps, and fabric. The amount of fabric keep the placket closed. needed will be twice the length of your skirt, including 3" for hem plus 5" for waistband. Figure 2 Measure and Cut 1. Straighten the fabric. 2. If you are using 2 lengths for the skirt, cut a 5-1/8" strip across the fabric for the band. -

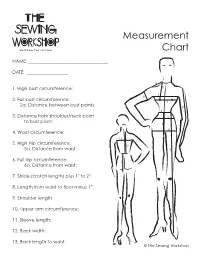

Measurement Chart

Measurement Chart NAME: ___________________________________ DATE: __________________ 1. High bust circumference: 2. Full bust circumference: 2a. Distance between bust points: 3. Distance from shoulder/neck point to bust point: 4. Waist circumference: 5. High Hip circumference: 5a. Distance from waist: 6. Full hip circumference: 6a. Distance from waist: 7. Stride (crotch length) plus 1" to 2": 8. Length from waist to floor minus 1": 9. Shoulder length: 10. Upper arm circumference: 11. Sleeve length: 12. Back width: 13. Back length to waist: © The Sewing Workshop Fitting the Bust: Ease Chart Garment Minimum Bust Ease Blouse, Dress 2½" to 3" Unlined jacket 3" to 4" Lined jacket 3½" to 4½" Coat 4" to 5" Fitting the Bust: Ease Chart © The Sewing Workshop Fitting the Back: Ease Chart Garment Minimum Back Ease Blouse, Dress ½" to 1" Jacket 1" Coat 1" to 2" Fitting the Back: Ease Chart © The Sewing Workshop Fitting Sleeves: Ease Chart Garment Minimum Upper Arm Ease Blouse 1" to 1½" Dress 1½" to 2" Unlined jacket 3" to 4" Lined jacket 3" to 4½" Coat 4" to 5½" Fitting Sleeves: Ease Chart © The Sewing Workshop Fitting Pants: Ease Chart Minimum Pants Ease Waist 1" to 2" Hip 2" - Fitted Pants 4" - Elastic Waist Pants Crotch Length 1" - If hips are less than 37" 1½" - If hips are 37"-40" 2" - If hips are 40" or more Fitting Pants: Ease Chart © The Sewing Workshop How to Measure For Successful Fitting by Linda Lee Tips! Tips! Tips! Gather Your Tools Know Your Notions Two very specific tools are recommended: Elastic - Use 1”-wide Stretchrite woven polyester flat non-roll elastic. -

Conceptual Design of Seat Belt Installation for Rear-Facing Child Car Seat

Conceptual Design of Seat Belt Installation for Rear-facing Child Car Seat Johan Niklasson Industrial Design Engineering, master's level 2019 Luleå University of Technology Department of Business Administration, Technology and Social Sciences Conceptual Design of Seat Belt Installation for Rear-facing Child Car Seat Johan Niklasson 2019 SUPERVISOR: Åsa Wikberg Nilsson REVIEWER: Linnea Halatchev & Lisa Helm EXAMINER: Peter Törlind MSc in INDUSTRIAL DESIGN ENGINEERING Department of Business Administration, Technology and Social Sciences Luleå University of Technology CIVILINGENJÖR I TEKNISK DESIGN Master of Science Thesis in Industrial Design Engineering Conceptual Design of Seat Belt Installation for Rear-Facing Child Car Seat © Johan Niklasson Published and distributed by Luleå University of Technology SE-971 87 Luleå, Sweden Telephone: + 46 (0) 920 49 00 00 Cover: Illustration by Johan Niklasson All illustrations and photos belong to the author if nothing else is stated. Printed in Luleå Sweden by Luleå University of Technology Reproservice Luleå, 2019 Acknowledgement I would like to express my special thanks of gratitude to my supervisor Åsa Wikberg Nilsson from Luleå University of Technology and Pernilla Alexandersson at Havd Group. You helped me with guidance through the project which helped me come forward in the project. Also, special thanks to Anton Wall at Company X who gave me the opportunity to do this interesting project and your support. I learned so many new things during this project which have given me invaluable knowledge. I would especially like to thank the staff at Havd Group for not only their generous support with expertise but also letting me use their facility. -

Sewing Fun! Feather

Sewing Fun! Feather. Blanket. Straight. Cross. Satin. Zig-zag. Chain. Running. Back. Whip. Slip. Knotting. These are not yoga poses! These are stitches that you can learn as you become a sewing master! Sewing is an essential skill that is practical and fun! Lose a button? No need to ask mom for help! You can fix it yourself! Want to create a personalized gift for someone? Sew it! Make your own bedroom accessories, stuffed animals, pencil cases, tote bags, blankets, pillows, doll clothes, design your own fashion. Dream it! Sew it! How to earn the Summer Reading patch the Girl Scout way: Steps: 1. Discover—Gather the materials you need and practice a few stitches. 2. Connect—Complete your first sewing project. 3. Take Action—Put your new skill to use! Materials Needed: In order to complete this patch, you’ll need a few things: • basic sewing supplies (See Step 1 for list or purchase an embroidery kit) • fabric: scraps or embroidery cloth • sewing resources: You can either go online with an adult, ask a professional, or visit your public library • a box or basket to use as your sewing kit • a quilting hoop • buttons STEP 1 Discover the basics of sewing. Before you start a project, it’s important to have all the tools you may need on hand. An easy way to gather everything is to create a sewing kit. Here are some items that you might want to have before you begin: • needles • thread • embroidery floss • needle threader • scissors • seam ripper • pins Optional: • measuring tools 800-248-3355 • marking tools gswpa.org • painter’s tape/colored tape (This is great for learning to sew straight lines!) Use your resources wisely to learn about hand sewing—you can find books about different kinds of stitches at your local library, or with the help of an adult, go online! There are websites and videos that can show you how to do easy, intermediate, and complicated stitches. -

It's All in the Details: Making an Early 19Th Century Ball Gown by Hope Greenberg

It's All in the Details: Making an early 19th Century Ball Gown By Hope Greenberg In 1775, the year of Jane Austen’s birth, women wore gowns with a fitted bodice, the waist at or below the natural waistline, and full skirts over a visible, often ornate, petticoat. They were made in a variety of heavy silks, cotton or wool. By the time she had reached her late teens the ornate gowns were being replaced by simple, lightweight, often sheer cotton or silk gowns that reflected the ideals of classicism. This guide provides images and details to consider when creating an early 19th century ballgown. The examples provide a general guide, not an exact historic timeline. Fashion is flexible: styles evolve and are adopted at a different pace depending on the wearer's age, location, and economic or social status. These examples focus on evening or ball gowns. Day dresses, walking dresses, and carriage dresses, while following the same basic silhouettes, have their own particular design details. Even evening gowns or opera gowns can usually be distinguished from ball gowns which, after all, must be designed for dancing! By focusing on the details we can see both the evolution of fashion for this period and how best to re-create it. What is the cut of the bodice, the sleeve length, or the height of the bustline? How full is the skirt, and where is that fullness? What colors are used? What type of fabric? Is there trim? If so, how much, what kind, and where is it placed? Based on the shape of the gown, what can we tell about the foundation garments? Paying attention to all these details will help you create a gown that is historically informed as well as beautiful. -

REMODELING CLOTHING Published and Distributed in Furtherance of the Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, by the Colorado State College, Extension Service, F

D-36 REMODELING CLOTHING Published and distributed in furtherance of the Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, by the Colorado State College, Extension Service, F. A. Anderson, Director, and U. S. Department of Agriculture cooperating. FORT COLLINS, COLO. MAY 1942 Remodeling Clothing By l\IARTHA ULRICH, Clothing Specialist Now is the time to DEFEND YOUR CLOTHING DOLLAR. START AT HOME! Inventory Plan Clean Sew Save The above may challenge you regarding the "Ordinary run of clothes in your wardrobe." Why not mix interest with your useful garments and at the same time- Save your dollars so that you may be able to: 1. Buy shoes, hose, and piece goods no longer made in the home. 2. Save the part of the price of a ready-made garment that goes for labor and wages that have increased by leaps and bounds. 3. Have the quality of garment you are accustomed to but which the rise in prices now prohibits. 4. Have money for other things that add to the comfort and convenience of your family. Inventory.-\Vhat do you have on hand? How much of it is worth using again? Plan.-How large a wardrobe does your range of activities require? Where can changes be made to streamline the old garments? What new items will be needed? How can you take care of the matter financially? Study the mode-do not ignore fashion but rather adapt the mode to yourself. Clean.-1. Rip old garment apart if it is to be re-cut. a. If it is to be cut down, save time by cutting it apart at the seams. -

Title Page GOOD

Art Around the Belly: Tracing the Cultural Significance and Artistic Value of Belt Hooks in Ancient China by Kara Kaifang Ma A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Kara Kaifang Ma 2014 ! Art Around the Belly: Tracing the Cultural Significance and Artistic Value of Belt Hooks in Ancient China Kara Kaifang Ma Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2014 Abstract The belt hook was used to fasten garments in ancient China long before the existence of belt buckles or plaques. Its use first appeared more than five thousand years ago and can be prevalently observed in paintings, on statuettes, and even on the famous Terracotta Army. Although it was such a common personal ornament, little has been written on this subject. My thesis will explore, through excavation data, coupled by my research on the extensive collection of belt hooks at the Royal Ontario Museum, how the examination of these ancient Chinese ornaments can not only reveal the status and wealth of its wearer, but also the cultural complexities and social advancements of that time. ! ! ! !ii Acknowledgments I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Dr. Chen Shen, my supervisor and mentor, who’s expertise and passion for his field has led me to pursue a career in East Asian Studies. Thank you for always pushing me to do better, the completion of my Master’s would not have been possible without your continuing support, guidance, and encouragement. -

Sewing Assistant 5-1

5. Sewing Assistant 5-1 Sewing Assistant Your Creative Assistant can be accessed at any time by tou- ching on the tool bar. Touch to open your Sewing and Embroidery Assistant. Your Sewing Assistant contains information on the most important professional sewing techniques for a wide range of fabrics, and details of which sewing machine accessories to use. The following pages explain different basic sewing techni- ques. Explore your Sewing Assistant to discover more exten- sive information about fabrics, sewing techniques and appli- cations. 5-2 5. Sewing Assistant Non-stretch seams Straight stitch Stitch no. 1 is the basic straight stitch in center needle position. The stitch length can be increased up to 6 mm as required. Some sewing techniques can be accomplished more easily by changing the needle position, such as topstitching a collar or sewing in a zipper. Your Pfaff creative 2144 features 19 needle positions, which can be adjusted with . When changing the needle position make sure that the needle is at the highest positi- on. Programmable seam length for straight stitch Stitch no. 1 Stitch no. 1 allows you to program a set seam length by tou- ching after you have touched the icon. Place the fabrics right sides together under the presser foot. Sew the first seam. When you have sewn the desired seam length, press the C reverse button. The machine will tie of at the beginning and end of the seam. You can repeat the programmed seam with the same length as often as you choose (see page 3-8 for a more detailed description). -

Reverse Logistics in Automotive Industry --A Multiple Case Study in Automotive Industry

Reverse Logistics in Automotive Industry --A multiple case study in automotive industry Zhaoanjian Mao & Yang Jin May 2014 Supervisor: Lars Löfqvist Examiner: Lars Bengtsson Student thesis, Master (one year), 15 HE Industrial engineering and management ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We want to present our appreciation to all those who helped us and provide us information with supporting during the whole period of writing the thesis. We would like to express our deepest and heartfelt gratitude goes first to our supervisor Lars Löfqvist, thanks for his patience, encouragement and constant guidance the whole process of our work, we may not reach the present form of the thesis without the consistent and elaborative guiding from our supervisor. Moreover, we also want to show our grateful to all the interviewees who are willing to give us a hand with the interviews of the case companies, thanks for the kindness of providing with information of the case company to all the managers. At last, we would like to thank our beloved parents who have been encouraging and supporting us out of dilemmas without any complaints all the time. Gävle, June 2014 Jin Yang & Mao Zhaoanjian ABSTRACT As nowadays’ forward logistics of automobile industry have been developed in a good stage, according to various car manufacturers; third-party logistics companies are more concerned about the car forward logistics. However, with the mature of automotive consumer market competition, innovation and the rise of global environmental awareness, the car reverse logistics must be given due attention as well. The economic value of reverse logistics has become increasingly prominent, lead to a scene of focus only on the car forward logistics is not enough. -

View an Extract of Sharp Suits Here

“Men wear a suit because it’s the gear of the gentleman the world over. ” Hardy Amies, The Englishman’s Suit SHARP SUITEric MuS sgrave Foreword by Richard James Foreword by Richard James 6 CONTENTS Introduction 8 Chapter One Convention or Fashion? 12 The single-breasted suit 32 Chapter Two A Question of Balance 34 The double-breasted suit 54 Chapter Three Princes Among Men 56 The striped suit 72 Chapter Four The Italian Job 74 The checked suit 92 Chapter Five US Male 94 The white suit 114 Chapter Six Passion From Paris 116 The Dormeuil suits 132 Chapter Seven Lost in Music 136 The Bowie suits 160 Chapter Eight The Magic of the Movies 164 Timeline 188 Index 194 Endnotes 197 Bibliography 198 Acknowledgements 199 Cover: (Front) From 1966, this high-fastening six-button suit by Ted Lapidus, tailor Douglas Hayward. Usually a casual dresser, McQueen wore the suits worn with all the right accessories for a gentleman, displays the passion of Paris. for several weeks before filming began to get used to the feel of fine tailoring. (Back) Cary Grant radiates class in a 1940s double-breasted suit. Left: It takes a lot of height and a lot of personal style to carry off an eight- Endpapers: Scenes from the Brioni hand-tailoring workshop in Penne, Italy. button double-breasted suit, no matter how well cut. Spanish nobleman Don Jaime de Mesia Figueroa shows us how it’s done while striking a pose Page 2: Steve McQueen reaches the pinnacle of style in The Thomas Crown next to his Matra sports car in about 1967. -

UNDERSTANDING a SEWING PATTERN the PATTERN ENVELOPE (FRONT) • on the Front of the Pattern Envelope, There Are Several Style Variations of the Same Project

UNDERSTANDING A SEWING PATTERN THE PATTERN ENVELOPE (FRONT) • On the front of the pattern envelope, there are several style variations of the same project. These style variations are called views. – One view may have a collar, long sleeves, and cuffs. Another view may have a V-neck and short sleeves. • These give you style options for this particular pattern. THE PATTERN ENVELOPE (BACK) • Contains information on: – Project in detail. – Description of the project by view. – How much fabric to buy, what fabric to buy. – One way designs- words, pictures, elephants – Notions- buttons (size), zippers (length), elastic, snaps, hook and eyes, etc. INSIDE THE PATTERN ENVELOPE • Pattern pieces • Key and glossary • Pattern layout • Step By Step instructions or guide sheet CUTTING LINES FOR DIFFERENT SIZES • A multi-sized sewing patterns will have the cutting lines for different sized pattern pieces nested within each other. • The different sizes are usually differentiated by different styles of dashed lines. • Pick out the lines that match your size – you may find it helpful to draw over them in a colored pen. • These are the lines you should be cutting to get your pattern pieces. CUTTING YOUR PATTERN PIECES • Accurately laying out a sewing pattern is an essential part of constructing any project. • Check the guide sheet to see which pattern pieces you need for the view you have chosen. – Make sure you cut the piece correctly and not cut off the marker points. • Press the paper or tissue pattern pieces with a warm, dry iron. GRAINLINE • a long, double-pointed arrow across your pattern pieces that indicated the grainline (lengthwise thread direction) of the fabric.