Cuneiform Digital Library Preprints Number 19.0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eoN - Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa University of Copenhagen Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Gaspa, Salvatore, "Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eN o-Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 3. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The Neo- Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa, University of Copenhagen In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. -

The Circulation of Astronomical Knowledge Between Babylon and Uruk

chapter 4 The Circulation of Astronomical Knowledge between Babylon and Uruk John M. Steele 1 Introduction Substantial numbers of Late Babylonian cuneiform tablets containing astro- nomical and astrological texts have only been found at two sites in Mesopo- tamia: Babylon and Uruk. Between four-and-a-half and five thousand tablets covering the complete range of observational, predictive, and mathematical astronomy, celestial divination, and astrology are known from Babylon. The number of astronomical tablets that have been recovered from Uruk is smaller, numbering approximately two hundred and fifty, but covers the same range of genres of astronomy as the tablets from Babylon. By contrast, only a handful of astronomical tablets have been found at other Late Babylonian sites—less than ten each from Nippur, Sippar and Ur. Whether this reflects a lack of astronom- ical activity in these cities or simply that the archives containing astronomical texts have not been discovered remains an open question.1 The aim of this article is to explore the relationship between astronomy at Babylon and Uruk during the Achaemenid and Seleucid periods: Did astro- nomical knowledge and/or astronomical texts circulate between Babylon and Uruk?2 If so, did that knowledge travel in both directions or only from one city to another? Were there local traditions of astronomical practice in these two cities? In order to answer these questions I compare the preserved examples 1 For simplicity, throughout this article I will generally use “astronomy” and “astronomical texts” to refer to all branches of astronomy and astrology. 2 The circulation of astronomical knowledge and the circulation of astronomical texts are related but not identical processes. -

A Nebuchadnezzar Cylinder (With Illustrations)

A NEBUCHADNEZZAR CYLINDER. BY EDGAR J. BANKS. IN recent years the Babylonian Arabs have learned a new industry from the excavators, for when no more lucrative employment is to be had, they become archeologists, and though it is forbidden to excavate for antiquities without special permission, they roam about the desert digging into the ruins at will. A day's journey to the south of Babylon, near the Euphrates, is a ruin mound so small that it has scarcely attracted the attention of the explorers. It is marked upon the maps as Wannet es-Sa'adun, but among the Arabs of the surrounding region it is known as Wana Sadoum. During the past two years this mound has been the scene of the illicit labor of the Arabs. The greatest of all ancient builders was Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon from 604 to 561 B. C. There is scarcely a ruin in all southern Mesopotamia which does not contain bricks stamped with his name, or some other evidences of his activity. He de- lighted in restoring the ancient temples which had long been in ruins, and in supporting the neglected sacrifices to the gods. He preferred to build new cities and enlarge the old ones rather than to wage war. Few of his records hint of military expeditions, for he was a man of peace, and it is as a builder or restorer of old temples that he should best be known. That his name might be remembered it was his custom, when restoring a temple, to in- scribe large cylinders of clay with his building records, and to bury them in the walls of the structure. -

Women and Their Agency in the Neo-Assyrian Empire

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto WOMEN AND THEIR AGENCY IN THE NEO-ASSYRIAN EMPIRE Assyriologia Pro gradu Saana Teppo 1.2.2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements................................................................................................................5 1. INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................6 1.1 Aim of the study...........................................................................................................6 1.2 Background ..................................................................................................................8 1.3 Problems with sources and material.............................................................................9 1.3.1 Prosopography of the Neo-Assyrian Empire ......................................................10 1.3.2 Corpus of Neo-Assyrian texts .............................................................................11 2. THEORETICAL APPROACH – EMPOWERING MESOPOTAMIAN WOMEN.......13 2.1 Power, agency and spheres of action .........................................................................13 2.2 Women studies and women’s history ........................................................................17 2.3 Feminist scholarship and ancient Near East studies ..................................................20 2.4 Problems relating to women studies of ancient Near East.........................................24 -

“Going Native: Šamaš-Šuma-Ukīn, Assyrian King of Babylon” Iraq

IRAQ (2019) Page 1 of 22 Doi:10.1017/irq.2019.1 1 GOING NATIVE: ŠAMAŠ-ŠUMA-UKĪN, ASSYRIAN KING OF BABYLON By SHANA ZAIA1 Šamaš-šuma-ukīn is a unique case in the Neo-Assyrian Empire: he was a member of the Assyrian royal family who was installed as king of Babylonia but never of Assyria. Previous Assyrian rulers who had control over Babylonia were recognized as kings of both polities, but Šamaš-šuma-ukīn’s father, Esarhaddon, had decided to split the empire between two of his sons, giving Ashurbanipal kingship over Assyria and Šamaš-šuma-ukīn the throne of Babylonia. As a result, Šamaš-šuma-ukīn is an intriguing case-study for how political, familial, and cultural identities were constructed in texts and interacted with each other as part of royal self- presentation. This paper shows that, despite Šamaš-šuma-ukīn’s familial and cultural identity as an Assyrian, he presents himself as a quintessentially Babylonian king to a greater extent than any of his predecessors. To do so successfully, Šamaš-šuma-ukīn uses Babylonian motifs and titles while ignoring the Assyrian tropes his brother Ashurbanipal retains even in his Babylonian royal inscriptions. Introduction Assyrian kings were recognized as rulers in Babylonia starting in the reign of Tiglath-pileser III (744– 727 BCE), who was named as such in several Babylonian sources including a king list, a chronicle, and in the Ptolemaic Canon.2 Assyrian control of the region was occasionally lost, such as from the beginning until the later years of Sargon II’s reign (721–705 BCE) and briefly towards the beginning of Sennacherib’s reign (704–681 BCE), but otherwise an Assyrian king occupying the Babylonian throne as well as the Assyrian one was no novelty by the time of Esarhaddon’s kingship (680–669 BCE). -

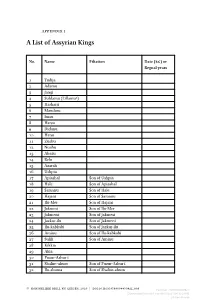

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years -

A NEO-ASSYRIAN LITERARY TEXT Andrew R. GEORGE

A NEO-ASSYRIAN LITERARY TEXT Andrew R. GEORGE - London Many works of Standard Babylonian literature known from Neo-Assyrian copies include isolated Assyrianisms, but the number of literary texts which employ the Neo-Assyrian dialect is a small one. With the collection of these under a single cover scheduled for early publication by the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project of the Univer sity of Helsinki, opportunity is taken to present an edition to the genre, an almost complete tablet from Ashurbanipal's libraries * . K. 1354 came to notice as a "list of temples" inBezold's Catalogue (p. 273, quoting 11.1-3 and 12-14), but while temples- and cities, too-feature prominently in the text, their enumeration is not for any topographical or lexical purpose. The listing of cities and temples, often in a set sequence, is a well-established and recurrent feature of Sumero-Babylonian liturgical literature. While not of the same tradition, the text preserved on K. 1354 also has the appearance of a cuI tic song. The text begins with a repeated formula which presents a long list of cult-centres and their temples (11. 1-17). Uruk is mentioned first, and then Babylon and Borsippa. These three cities are the subject of special attention, in that epithets mark them out as personal to the "voice" of the text ("my principal chamber, ... house of my pleasure, ... my ancestral home, etc."). But the repetition of Uruk, here and throughout the text, makes it clear that it is the Sumerian city which is the principal place of interest. -

Assyrian Period (Ca. 1000•fi609 Bce)

CHAPTER 8 The Neo‐Assyrian Period (ca. 1000–609 BCE) Eckart Frahm Introduction This chapter provides a historical sketch of the Neo‐Assyrian period, the era that saw the slow rise of the Assyrian empire as well as its much faster eventual fall.1 When the curtain lifts, at the close of the “Dark Age” that lasted until the middle of the tenth century BCE, the Assyrian state still finds itself in the grip of the massive crisis in the course of which it suffered significant territorial losses. Step by step, however, a number of assertive and ruthless Assyrian kings of the late tenth and ninth centuries manage to reconquer the lost lands and reestablish Assyrian power, especially in the Khabur region. From the late ninth to the mid‐eighth century, Assyria experiences an era of internal fragmentation, with Assyrian kings and high officials, the so‐called “magnates,” competing for power. The accession of Tiglath‐pileser III in 745 BCE marks the end of this period and the beginning of Assyria’s imperial phase. The magnates lose much of their influence, and, during the empire’s heyday, Assyrian monarchs conquer and rule a territory of unprecedented size, including Babylonia, the Levant, and Egypt. The downfall comes within a few years: between 615 and 609 BCE, the allied forces of the Babylonians and Medes defeat and destroy all the major Assyrian cities, bringing Assyria’s political power, and the “Neo‐Assyrian period,” to an end. What follows is a long and shadowy coda to Assyrian history. There is no longer an Assyrian state, but in the ancient Assyrian heartland, especially in the city of Ashur, some of Assyria’s cultural and religious traditions survive for another 800 years. -

The Arabs of North Arabia in Later Pre-Islamic Times

The Arabs of North Arabia in later Pre-Islamic Times: Qedar, Nebaioth, and Others A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 Marwan G. Shuaib School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 The Contents List of Figures ……………………………………………………………….. 7 Abstract ………………………………………………………………………. 8 Declaration …………………………………………………………………… 9 Copyright Rules ……………………………………………………………… 9 Acknowledgements .….……………………………………………………… 10 General Introduction ……………………………………………………….. 11 Chapter One: Historiography ……………………………………….. 13 1.1 What is the Historian’s Mission? ……………………………………….. 14 1.1.1 History writing ………………………...……....……………….…... 15 1.1.2 Early Egyptian Historiography …………………………………….. 15 1.1.3 Israelite Historiography ……………………………………………. 16 1.1.4 Herodotus and Greek Historiography ……………………………… 17 1.1.5 Classical Medieval Historiography …………………….…………... 18 1.1.6 The Enlightenment and Historiography …………………………… 19 1.1.7 Modern Historiography ……………………………………………. 20 1.1.8 Positivism and Idealism in Nineteenth-Century Historiography…… 21 1.1.9 Problems encountered by the historian in the course of collecting material ……………………………………………………………………… 22 1.1.10 Orientalism and its contribution ………………………………….. 24 1.2 Methodology of study …………………………………………………… 26 1.2.1 The Chronological Framework ……………………………………. 27 1.2.2 Geographical ……………………………………………………….. 27 1.3 Methodological problems in the ancient sources…...………………….. 28 1.3.1 Inscriptions ………………………………………………………… 28 1.3.2 Annals ……………………………………………………………… 30 1.3.3 Biblical sources ...…………………………………………………... 33 a. Inherent ambiguities of the Bible ……………………………… 35 b. Is the Bible history at all? ……………………………………… 35 c. Difficulties in the texts …………………………………………. 36 3 1.4 Nature of the archaeological sources …………………………………... 37 1.4.1 Medieval attitudes to Antiquity ……………………………………. 37 1.4.2 Archaeology during the Renaissance era …………………………... 38 1.4.3 Archaeology and the Enlightenment ………………………………. 39 1.4.4 The nineteenth century and the history of Biblical archaeology……. -

After Babylon, Borsippa Has Its Eye on World Heritage List

After Babylon, Borsippa has its eye on World Heritage List A man walks down a road in the shadow of a Mesopotamian ziggurat (C) and a shrine to the Prophet Abraham (L) in Borsippa, Iraq, June 8, 2003. (photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images) BABIL, Iraq — As preparations continue to have Babylon recognized by the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2017, the city of Borsippa, which is 25 kilometers (15 miles) from the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon, is on the top of the list of archaeological sites that are most likely to be inscribed on the world list, as the city has not witnessed any construction changes beyond UNESCO specifications. Summary⎙ Print The ancient city of Borsippa in the south of Iraq incorporates religious and historical relics and is hoping to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Author Wassim BassemPosted August 29, 2016 TranslatorSahar Ghoussoub The city has not had a face-lift for thousands of years, Hussein Falih, the director of the archaeological site, told Al-Monitor. “The Department of Antiquities in Babil governorate is careful not to make any change that would reduce the historical value of the site and is keen on intensifying security measures and protection,” Falih said. “Working on inscribing Borsippa to the World Heritage List requires efforts to preserve thearchaeological hills of the city that also include valuable relics that have yet to be excavated. The city’s high tower should also be sustained in a scientific manner to prevent its collapse without changing its original structure. We ought also to embark on a media campaign to promote this ancient archaeological site,” Falih added.