Apuleius and Carthage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life with Augustine

Life with Augustine ...a course in his spirit and guidance for daily living By Edmond A. Maher ii Life with Augustine © 2002 Augustinian Press Australia Sydney, Australia. Acknowledgements: The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following people: ► the Augustinian Province of Our Mother of Good Counsel, Australia, for support- ing this project, with special mention of Pat Fahey osa, Kevin Burman osa, Pat Codd osa and Peter Jones osa ► Laurence Mooney osa for assistance in editing ► Michael Morahan osa for formatting this 2nd Edition ► John Coles, Peter Gagan, Dr. Frank McGrath fms (Brisbane CEO), Benet Fonck ofm, Peter Keogh sfo for sharing their vast experience in adult education ► John Rotelle osa, for granting us permission to use his English translation of Tarcisius van Bavel’s work Augustine (full bibliography within) and for his scholarly advice Megan Atkins for her formatting suggestions in the 1st Edition, that have carried over into this the 2nd ► those generous people who have completed the 1st Edition and suggested valuable improvements, especially Kath Neehouse and friends at Villanova College, Brisbane Foreword 1 Dear Participant Saint Augustine of Hippo is a figure in our history who has appealed to the curiosity and imagination of many generations. He is well known for being both sinner and saint, for being a bishop yet also a fellow pilgrim on the journey to God. One of the most popular and attractive persons across many centuries, his influence on the church has continued to our current day. He is also renowned for his influ- ence in philosophy and psychology and even (in an indirect way) art, music and architecture. -

The Expansion of Christianity: a Gazetteer of Its First Three Centuries

THE EXPANSION OF CHRISTIANITY SUPPLEMENTS TO VIGILIAE CHRISTIANAE Formerly Philosophia Patrum TEXTS AND STUDIES OF EARLY CHRISTIAN LIFE AND LANGUAGE EDITORS J. DEN BOEFT — J. VAN OORT — W.L. PETERSEN D.T. RUNIA — C. SCHOLTEN — J.C.M. VAN WINDEN VOLUME LXIX THE EXPANSION OF CHRISTIANITY A GAZETTEER OF ITS FIRST THREE CENTURIES BY RODERIC L. MULLEN BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mullen, Roderic L. The expansion of Christianity : a gazetteer of its first three centuries / Roderic L. Mullen. p. cm. — (Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae, ISSN 0920-623X ; v. 69) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-13135-3 (alk. paper) 1. Church history—Primitive and early church, ca. 30-600. I. Title. II. Series. BR165.M96 2003 270.1—dc22 2003065171 ISSN 0920-623X ISBN 90 04 13135 3 © Copyright 2004 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands For Anya This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................ ix Introduction ................................................................................ 1 PART ONE CHRISTIAN COMMUNITIES IN ASIA BEFORE 325 C.E. Palestine ..................................................................................... -

Terror/Torture Karima Bennoune

Berkeley Journal of International Law Volume 26 | Issue 1 Article 1 2008 Terror/Torture Karima Bennoune Recommended Citation Karima Bennoune, Terror/Torture, 26 Berkeley J. Int'l Law. 1 (2008). Available at: http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/bjil/vol26/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals and Related Materials at Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Berkeley Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bennoune: Terror/Torture Terror/Torture By Karima Bennoune* ABSTRACT In the face of terrorism, human rights law's requirement that states "respect and ensure" rights necessitates that states take active steps to safeguard their populations from violent attack, but in so doing do not violate rights. Security experts usually emphasize the aspect of ensuring rights while human rights ad- vocates largely focus on respecting rights. The trick, which neither side in the debate has adequately referenced, is that states have to do both at the same time. In contrast to these largely one-sided approaches, adopting a radical universalist stance, this Article argues that both contemporary human rights and security dis- courses on terrorism must be broadened and renewed. This renewal must be in- formed by the understanding that international human rights law protects the in- dividual both from terrorism and the excesses of counter-terrorism, like torture. To develop this thesis, the Article explores the philosophical overlap between both terrorism and torture and their normative prohibitions. -

A New Examination of the Arch of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus at Oea Rachel Meyers Iowa State University, [email protected]

World Languages and Cultures Publications World Languages and Cultures 2017 A New Examination of the Arch of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus at Oea Rachel Meyers Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/language_pubs Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the History of Gender Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ language_pubs/130. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the World Languages and Cultures at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages and Cultures Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A New Examination of the Arch of Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus at Oea Abstract The ra ch dedicated to Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus at Oea was an important component in that town’s building activity. By situating the arch within its socio-historical context and acknowledging the political identity of Oea and nearby towns, this article shows that the arch at Oea far surpassed nearby contemporary arches in style, material, and execution. Further, this article demonstrates that the arch was a key element in Oea’s Roman identity. Finally, the article bridges disciplinary boundaries by bringing together art historical analysis with the concepts of euergetism, Roman civic status, and inter-city rivalry in the Roman Empire. -

Perspektiven Der Spolienforschung 2. Zentren Und Konjunkturen Der

Perspektiven der Spolienforschung Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler (eds.) BERLIN STUDIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD antiker Bauten, Bauteile und Skulpturen ist ein weitverbreite- tes Phänomen der Nachantike. Rom und der Maghreb liefern zahlreiche und vielfältige Beispiele für diese An- eignung materieller Hinterlassenscha en der Antike. Während sich die beiden Regionen seit dem Ausgang der Antike politisch und kulturell sehr unterschiedlich entwickeln, zeigen sie in der praktischen Umsetzung der Wiederverwendung, die zwischenzeitlich quasi- indus trielle Ausmaße annimmt, strukturell ähnliche orga nisatorische, logistische und rechtlich-lenkende Praktiken. An beiden Schauplätzen kann die Antike alternativ als eigene oder fremde Vergangenheit kon- struiert und die Praxis der Wiederverwendung utili- taristischen oder ostentativen Charakter besitzen. 40 · 40 Perspektiven der Spolien- forschung Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © Edition Topoi / Exzellenzcluster Topoi der Freien Universität Berlin und der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Abbildung Umschlag: Straßenkreuzung in Tripolis, Photo: Stefan Altekamp Typographisches Konzept und Einbandgestaltung: Stephan Fiedler Printed and distributed by PRO BUSINESS digital printing Deutschland GmbH, Berlin ISBN ---- URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:- First published Published under Creative Commons Licence CC BY-NC . DE. For the terms of use of the illustrations, please see the reference lists. www.edition-topoi.org INHALT , -, Einleitung — 7 Commerce de Marbre et Remploi dans les Monuments de L’Ifriqiya Médiévale — 15 Reuse and Redistribution of Latin Inscriptions on Stone in Post-Roman North-Africa — 43 Pulcherrima Spolia in the Architecture and Urban Space at Tripoli — 67 Adding a Layer. -

The Transatlantic Cocaine Market

Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel.: (+43-1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org The Transatlantic Cocaine Market Research Paper United Nations publication FOR UNITED NATIONS USE ONLY ISBN ???-??-?-??????-? ISSN ????-???? Sales No. T.08.XI.7 Printed in Austria ST/NAR.3/2007/1 (E/NA) job no.—Date—copies April 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by the Studies and Threat Analysis Section in collaboration with the Regional Office in Senegal and the Integrated Programme and Oversight Branch of UNODC. The following staff members contributed to this document: Studies and Threat Analysis Section: Thibault Le Pichon, Thomas Pietschmann, Ted Leggett, Raggie Johansen Regional Office in Senegal: Alexandre Schmidt, David Izadifar Integrated Programme and Oversight Branch: Aisser Al-Hafedh, Olivier Inizan Strategic Planning Unit: Gautam Babbar DISCLAIMER This report has not been formally edited. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNODC concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the Member States. The Transatlantic Cocaine Market Key findings....................................................................................................................... 2 Key data / estimates ......................................................................................................... -

The End of Local Magistrates in the Roman Empire

The end of local magistrates in the Roman Empire Leonard A. CURCHIN University of Waterloo, Canadá [email protected] Recibido: 15 de julio de 2013 Aceptado: 10 de diciembre de 2013 ABSTRACT Previous studies of the status of local magistrates in the Late Empire are unsatisfying and fail to explain when and why local magistracies ended. With the aid of legal, epigraphic, papyrological and literary sources, the author re-examines the functions and chronology of both regular and quasi-magistrates, among them the curator, defensor and pater civitatis. He finds that the expense of office-holding was only part of the reason for the extinction of regular magistracies. More critical was the failure of local magistrates to control finances and protect the plebeians. Key words: Cursus honorum. Late Roman Empire. Roman administration. Roman cities. Roman gov- ernment. Roman magistrates. El fin de los magistrados locales en el Imperio romano RESUMEN Los estudios previos relativos a la condición de los magistrados locales durante el Bajo Imperio son poco satisfactorios, porque dejan sin aclarar cuándo y cómo se extinguieron las magistraturas locales. Con ayuda de fuentes jurídicas, epigráficas, papirológicas y literarias, el autor examina de nuevo las funciones y la cronología de magistrados regulares y cuasi-magistrados, como el curator, el defensor y el pater civitatis. Se considera que los gastos aparejados a los cargos públicos explican sólo en parte la extinción de las magistraturas regulares; más crucial fue, en este sentido, el hecho de que los magistra- dos locales de este período fallasen a la hora de restringir los gastos o de proteger a los plebeyos. -

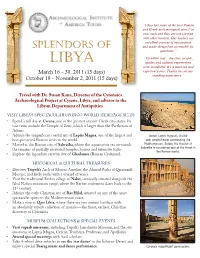

Splendors of and Made Themselves Accessible for Questions.”

“Libya has some of the best Roman and Greek archaeological sites I’ve ever seen and they are not overrun with other tourists. Our leaders are excellent sources of information SplendorS of and made themselves accessible for questions.” “Excellent tour—the sites, people, libya guides and cultural experiences were wonderful. It’s a must see and March 16 – 30, 2011 (15 days) experience tour. Thanks for an out- October 19 – November 2, 2011 (15 days) standing experience.” Travel with Dr. Susan Kane, Director of the Cyrenaica Archaeological Project at Cyrene, Libya, and advisor to the Libyan Department of Antiquities. VISIT LIBYA’S SPECTACULAR UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITES: • Spend a full day at Cyrene, one of the greatest ancient Greek city-states. Its vast ruins include the Temple of Zeus, which is larger than the Parthenon of Athens. • Admire the magnificent coastal site of Leptis Magna, one of the largest and Above, Leptis Magna’s 16,000 seat amphitheater overlooking the best-preserved Roman cities in the world. Mediterranean. Below, the theater at • Marvel at the Roman city of Sabratha, where the aquamarine sea surrounds Sabratha is considered one of the finest in the remains of partially excavated temples, houses and extensive baths. the Roman world. • Explore the legendary caravan city of Ghadames (Roman Cydamus). HISTORICAL & CULTURAL TREASURES • Discover Tripoli’s Arch of Marcus Aurelius, the Ahmad Pasha al Qaramanli Mosque, and lively souks with a myriad of wares. • Visit the traditional Berber village of Nalut, scenically situated alongside the Jabal Nafusa mountain range, where the Berber settlement dates back to the 11th century. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 05 June 2020 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Hellstrom, Monica (2020) 'Epigraphy and ambitions : building inscriptions in the hinterland of Carthage.', Journal of Roman studies., 110 . pp. 57-90. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0075435820001380 Publisher's copyright statement: This article has been published in a revised form in The Journal of Roman Studies. This version is published under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND. No commercial re-distribution or re-use allowed. Derivative works cannot be distributed. c The Author(s). Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk 1 Epigraphy and Ambitions: Building Inscriptions in the Hinterland of Carthage MONICA HELLSTRÖM* Building inscriptions are not a good proxy for building activity or, by extension, prosperity. In the part of Roman North Africa where they are the most common, the majority of the surviving building inscriptions document the construction of religious buildings by holders of local priesthoods, usually of the imperial cult. -

Roman North Africa North Roman

EASTERNSOCIAL WORLDS EUROPEAN OF LATE SCREEN ANTIQUITY CULTURES AND THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES Cilliers Roman North Africa Louise Cilliers Roman North Africa Environment, Society and Medical Contribution Roman North Africa Social Worlds of Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages The Late Antiquity experienced profound cultural and social change: the political disintegration of the Roman Empire in the West, contrasted by its continuation and transformation in the East; the arrival of ‘barbarian’ newcomers and the establishment of new polities; a renewed militarization and Christianization of society; as well as crucial changes in Judaism and Christianity, together with the emergence of Islam and the end of classical paganism. This series focuses on the resulting diversity within Late Antique society, emphasizing cultural connections and exchanges; questions of unity and inclusion, alienation and conflict; and the processes of syncretism and change. By drawing upon a number of disciplines and approaches, this series sheds light on the cultural and social history of Late Antiquity and the greater Mediterranean world. Series Editor Carlos Machado, University of St. Andrews Editorial Board Lisa Bailey, University of Auckland Maijastina Kahlos, University of Helsinki Volker Menze, Central European University Ellen Swift, University of Kent Enrico Zanini, University of Siena Roman North Africa Environment, Society and Medical Contribution Louise Cilliers Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Ruins of the Antonine Baths in Carthage © Dreamstime Stockphoto’s Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Typesetting: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 990 0 e-isbn 978 90 4854 268 0 doi 10.5117/9789462989900 nur 684 © Louise Cilliers / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 All rights reserved. -

Djémila, Cuicul Romana Uma Perspectiva Sobre a Arquitectura Pública De Cuicul

FACULDADE DE ARQUITECTURA DA UNIVERSIDADE DO PORTO DJÉMILA, CUICUL ROMANA UMA PERSPECTIVA SOBRE A ARQUITECTURA PÚBLICA DE CUICUL Carlos Oliveira | Inês Vieira |Maria Isabel de Mendonça História da Arquitectura Antiga e Medieval | Docente Arq. Ana Neiva 1 Índice de Conteúdos Nota Prévia ................................................................................................................................... 3 Inserção Urbana e Território ........................................................................................................ 6 Traçado e Sistema de Composição ............................................................................................... 9 Fases de Construção ................................................................................................................ 14 Tipologias Públicas Romanas e a sua Organização Funcional no contexto da cidade .............. 17 Os Espaços Públicos ................................................................................................................ 19 Fórum do Capitólio .............................................................................................................. 20 Fórum dos Severos .............................................................................................................. 25 Bairro Cristão ....................................................................................................................... 28 Outros Equipamentos Públicos .............................................................................................. -

Paper Sample Riga

International Cartographic Association Commission on Cartographic Heritage into the Digital 14th ICA Conference Digital Approaches to Cartographic Heritage Conference Proceedings ISSN XXXX-XXXX - Thessaloniki, Greece, 8-10 May 2019 _____________________________________________________________________________________ Lyudmila Filatova1, Dmitri Gusev2, Sergey Stafeyev3 Iterative Reconstruction of Ptolemy’s West Africa Using Modern GIS Analysis Keywords: Claudius Ptolemy, ancient geography, GIS analysis, historical cartography, georeferencing Summary: The multifaceted and challenging problem of reconstructing Claudius Ptolemy’s map of ancient West Africa from the numeric coordinate data and other information found in his seminal ‘Geography’ and visualizing the results in modern projections using popular and powerful GIS tools, such as ArcGIS and Google Earth, is addressed by the authors iteratively. We apply a combination of several old and new techniques ranging from tradi- tional toponymic analysis to novel modifications of cluster analysis. Our hybrid human- machine method demonstrates that Ptolemy’s information on West Africa is a compilation of data from three or more sources, including at least one version or derivative of The Periplus of Hanno. The newest iteration adds data for three more provinces of Ptolemy’s Libya — Mauretania Caesariensis, Africa and Aethiopia Interior— to Mauretania Tingitana and Libya Interior investigated in an earlier, unpublished version of the work that the late Lyudmila Filatova had contributed to as the founder of our multi-year project. The surviv- ing co-authors used their newest digital analysis methods (triangulation and flocking with Bayesian correction) and took into account their recent finds on Ptolemy’s Sinae (Guinea/Senegal, where Ptolemy had placed fish-eating Aethiopians). We discuss some of the weaknesses and fallacies of the earlier approaches to the problem.