Effects of Dominant Scavengers on Solitary Predators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eurasian Lynx – Your Essential Brief

Eurasian lynx – Your essential brief Background Q: Are lynx native to Britain? A: Based on archaeological evidence, the range of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) included Britain until at least 1,300 years ago. It is difficult to be precise about when or why lynx became extinct here, but it was almost certainly related to human activity – deforestation removed their preferred habitat, and also that of their prey, thus reducing prey availability. These declines in prey species may have been exacerbated by human hunting. Q: Where do they live now? A: Across Europe, Scandinavia, Russia, northern China and Southeast Asia. The range used to include other areas of Western Europe, including Britain, where they are no longer present. Q: How many are there? A: There are thought to be around 50,000 in the world, of which 9,000 – 10,000 live in Europe. They are considered to be a species of least concern by the IUCN. Modern range of the Eurasian lynx Q: How big are they? A: Lynx are on average around 1m in length, 75cm tall and around 20kg, with the males being slightly larger than the females. They can live to 15 years old, but this is rare in the wild. Q: What do they eat? A: The preferred prey of the lynx are the smaller deer species, primarily the roe deer. Lynx may also prey upon other deer species, including chamois, sika deer, smaller red deer, muntjac and fallow deer. Q: Do they eat other things? A: Yes. Lynx prey on many other species when their preferred prey is scarce, including rabbits, hares, foxes, wildcats, squirrel, pine marten, domestic pets, sheep, goats and reared gamebirds. -

Status of Large Carnivores in Serbia

Status of large carnivores in Serbia Duško Ćirović Faculty of Biology University of Belgrade, Belgrade Status and threats of large carnivores in Serbia LC have differend distribution, status and population trends Gray wolf Eurasian Linx Brown Bear (Canis lupus) (Lynx lynx ) (Ursus arctos) Distribution of Brown Bear in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Brown Bear in Serbia Dinaric-Pindos: Distribution 10000 km2 N=100-120 Population increase Range expansion Carpathian East Balkan: Distribution 1400 km2 Dinaric-Pindos N= a few East Balkan Population trend: unknown Carpathian: Distribution 8200 km2 N=8±2 Population stable Legal status of Brown Bear in Serbia According Law on Protection of Nature and the Law on Game and Hunting brown bear in Serbia is strictly protected species. He is under the centralized jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environmental Protection Treats of Brown Bear in Serbia Intensive forestry practice and infrastructure development . Illegal killing Low acceptance due to fear for personal safety Distribution of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Dinaric-Balkan: 2 Carpathian Distribution cca 43500 km N=800-900 Population - stabile/slight increasingly Dinaric Range - slight expansion Carpathian: Distribution 480 km2 (was) Population – a few Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian population is still undefined Carpathian Peri-Carpathian Legal status of Gray wolf in Serbia According the Law on Game and Hunting the gray wolf in majority pars of its distribution (south from Sava and Danube rivers) is game species with closing season from April 15th to July 1st. -

Prey Density, Environmental Productivity and Home-Range Size in the Eurasian Lynx (Lynx Lynx)

J. Zool., Lond. (2005) 265, 63–71 C 2005 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom DOI:10.1017/S0952836904006053 Prey density, environmental productivity and home-range size in the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) Ivar Herfindal1, John D. C. Linnell2*, John Odden2, Erlend Birkeland Nilsen1 and Reidar Andersen1,2 1 Department of Biology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway 2 Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Tungasletta 2, N-7485 Trondheim, Norway (Accepted 19 May 2004) Abstract Variation in size of home range is among the most important parameters required for effective conservation and management of a species. However, the fact that home ranges can vary widely within a species makes data transfer between study areas difficult. Home ranges of Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx vary by a factor of 10 between different study areas in Europe. This study aims to try and explain this variation in terms of readily available indices of prey density and environmental productivity. On an individual scale we related the sizes of 52 home ranges, derived from 23 (9:14 male:female) individual resident lynx obtained from south-eastern Norway, with an index of density of roe deer Capreolus capreolus. This index was obtained from the density of harvested roe deer within the municipalities covered by the lynx home ranges. We found a significant negative relationship between harvest density and home- range size for both sexes. On a European level we related the sizes of 111 lynx (48:63 male: female) from 10 study sites to estimates derived from remote sensing of environmental productivity and seasonality. -

Current Status of the Eurasian Lynx. Cat News. (2016)

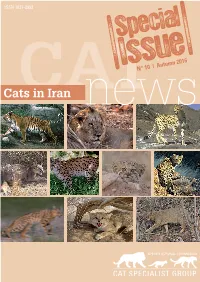

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 10 | Autumn 2016 CatsCAT in Iran news 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Cover Photo: From top left to bottom right: Caspian tiger (K. Rudloff) This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Asiatic lion (P. Meier) from the Wild Cat Club and Zoo Leipzig. Asiatic cheetah (ICS/DoE/CACP/ Panthera) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh caracal (M. Eslami Dehkordi) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser & Tabea Lanz Eurasian lynx (F. Heidari) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Pallas’s cat (F. Esfandiari) Persian leopard (S. B. Mousavi) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group Asiatic wildcat (S. B. Mousavi) sand cat (M. R. Besmeli) jungle cat (B. Farahanchi) The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

FRESHWATER CRABS in AFRICA MICHAEL DOBSON Dr M

CORE FRESHWATER CRABS IN AFRICA 3 4 MICHAEL DOBSON FRESHWATER CRABS IN AFRICA In East Africa, each highland area supports endemic or restricted species (six in the Usambara Mountains of Tanzania and at least two in each of the brought to you by MICHAEL DOBSON other mountain ranges in the region), with relatively few more widespread species in the lowlands. Recent detailed genetic analysis in southern Africa Dr M. Dobson, Department of Environmental & Geographical Sciences, has shown a similar pattern, with a high diversity of geographically Manchester Metropolitan University, Chester St., restricted small-bodied species in the main mountain ranges and fewer Manchester, M1 5DG, UK. E-mail: [email protected] more widespread large-bodied species in the intervening lowlands. The mountain species occur in two widely separated clusters, in the Western Introduction Cape region and in the Drakensburg Mountains, but despite this are more FBA Journal System (Freshwater Biological Association) closely related to each other than to any of the lowland forms (Daniels et Freshwater crabs are a strangely neglected component of the world’s al. 2002b). These results imply that the generally small size of high altitude inland aquatic ecosystems. Despite their wide distribution throughout the species throughout Africa is not simply a convergent adaptation to the provided by tropical and warm temperate zones of the world, and their great diversity, habitat, but evidence of ancestral relationships. This conclusion is their role in the ecology of freshwaters is very poorly understood. This is supported by the recent genetic sequencing of a single individual from a nowhere more true than in Africa, where crabs occur in almost every mountain stream in Tanzania that showed it to be more closely related to freshwater system, yet even fundamentals such as their higher taxonomy mountain species than to riverine species in South Africa (S. -

Phylogenetic and Phylogeographic Analysis of Iberian Lynx Populations

Journal of Heredity 2004:95(1):19–28 ª 2004 The American Genetic Association DOI: 10.1093/jhered/esh006 Phylogenetic and Phylogeographic Analysis of Iberian Lynx Populations W. E. JOHNSON,J.A.GODOY,F.PALOMARES,M.DELIBES,M.FERNANDES,E.REVILLA, AND S. J. O’BRIEN From the Laboratory of Genomic Diversity, National Cancer Institute-FCRDC, Frederick, MD 21702-1201 (Johnson and O’Brien), Department of Applied Biology, Estacio´ n Biolo´ gica de Don˜ana, CSIC, Avda. Marı´a Luisa s/n, 41013, Sevilla, Spain (Godoy, Palomares, Delibes, and Revilla), and Instituto da Conservac¸a˜o da Natureza, Rua Filipe Folque, 46, 28, 1050-114 Lisboa, Portugal (Fernandes). E. Revilla is currently at the Department of Ecological Modeling, UFZ-Center for Environmental Research, PF 2, D-04301 Leipzig, Germany. The research was supported by DGICYT and DGES (projects PB90-1018, PB94-0480, and PB97-1163), Consejerı´a de Medio Ambiente de la Junta de Andalucı´a, Instituto Nacional para la Conservacion de la Naturaleza, and US-Spain Joint Commission for Scientific and Technological Cooperation. We thank A. E. Pires, A. Piriz, S. Cevario, V. David, M. Menotti-Raymond, E. Eizirik, J. Martenson, J. H. Kim, A. Garfinkel, J. Page, C. Ferris, and E. Carney for advice and support in the laboratory and J. Calzada, J. M. Fedriani, P. Ferreras, and J. C. Rivilla for assistance in the capture of lynx. Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Don˜ana Biological Station scientific collection, Don˜ana National Park, and Instituto da Conservac¸a˜o da Natureza of Portugal provided samples of museum specimens. -

Interspecific Killing Among Mammalian Carnivores

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital.CSIC vol. 153, no. 5 the american naturalist may 1999 Interspeci®c Killing among Mammalian Carnivores F. Palomares1,* and T. M. Caro2,² 1. Department of Applied Biology, EstacioÂn BioloÂgica de DonÄana, thought to act as keystone species in the top-down control CSIC, Avda. MarõÂa Luisa s/n, 41013 Sevilla, Spain; of terrestrial ecosystems (Terborgh and Winter 1980; Ter- 2. Department of Wildlife, Fish, and Conservation Biology and borgh 1992; McLaren and Peterson 1994). One factor af- Center for Population Biology, University of California, Davis, fecting carnivore populations is interspeci®c killing by California 95616 other carnivores (sometimes called intraguild predation; Submitted February 9, 1998; Accepted December 11, 1998 Polis et al. 1989), which has been hypothesized as having direct and indirect effects on population and community structure that may be more complex than the effects of either competition or predation alone (see, e.g., Latham 1952; Rosenzweig 1966; Mech 1970; Polis and Holt 1992; abstract: Interspeci®c killing among mammalian carnivores is Holt and Polis 1997). Currently, there is renewed interest common in nature and accounts for up to 68% of known mortalities in some species. Interactions may be symmetrical (both species kill in intraguild predation from a conservation standpoint each other) or asymmetrical (one species kills the other), and in since top predator removal is thought to release other some interactions adults of one species kill young but not adults of predator populations with consequences for lower trophic the other. -

Predicting Global Population Connectivity and Targeting Conservation Action for Snow Leopard Across Its Range

Ecography 39: 419–426, 2016 doi: 10.1111/ecog.01691 © 2015 e Authors. Ecography © 2015 Nordic Society Oikos Subject Editor: Bethany Bradley. Editor-in-Chief: Miguel Araújo. Accepted 27 April 2015 Predicting global population connectivity and targeting conservation action for snow leopard across its range Philip Riordan, Samuel A. Cushman, David Mallon, Kun Shi and Joelene Hughes P. Riordan ([email protected]) and J. Hughes, Dept of Zoology, Univ. of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PS, UK. – S. A. Cushman, US Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 800 E Beckwith, Missoula, MT 59801, USA. – D. Mallon, Division of Biology and Conservation Ecology, School of Science and the Environment, Manchester Metropolitan Univ., Manchester, M1 5GD, UK. – K. Shi and PR, Wildlife Inst., College of Nature Conservation, Beijing Forestry Univ., 35, Tsinghua-East Road, Beijing 100083, China. Movements of individuals within and among populations help to maintain genetic variability and population viability. erefore, understanding landscape connectivity is vital for effective species conservation. e snow leopard is endemic to mountainous areas of central Asia and occurs within 12 countries. We assess potential connectivity across the species’ range to highlight corridors for dispersal and genetic flow between populations, prioritizing research and conservation action for this wide-ranging, endangered top-predator. We used resistant kernel modeling to assess snow leopard population connectivity across its global range. We developed an expert-based resistance surface that predicted cost of movement as functions of topographical complexity and land cover. e distribution of individuals was simulated as a uniform density of points throughout the currently accepted global range. -

The Joint Evolution of Animal Movement and Competition Strategies

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.452886; this version posted August 17, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. The joint evolution of animal movement and competition strategies Pratik R. Gupte1,a,∗ Christoph F. G. Netz1,a Franz J. Weissing1,∗ 1. Groningen Institute for Evolutionary Life Sciences, University of Groningen, Groningen 9747 AG, The Netherlands. ∗ Corresponding authors; e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] a Both authors contributed equally to this study. Keywords: Movement ecology, Intraspecific competition, Individual differences, Foraging ecol- ogy, Kleptoparasitism, Individual based modelling, Ideal Free Distribution 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.452886; this version posted August 17, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 Abstract 2 Competition typically takes place in a spatial context, but eco-evolutionary models rarely address 3 the joint evolution of movement and competition strategies. Here we investigate a spatially ex- 4 plicit producer-scrounger model where consumers can either forage on a heterogeneous resource 5 landscape or steal resource items from conspecifics (kleptoparasitism). We consider three scenar- 6 ios: (1) a population of foragers in the absence of kleptoparasites; (2) a population of consumers 7 that are either specialized on foraging or on kleptoparasitism; and (3) a population of individuals 8 that can fine-tune their behavior by switching between foraging and kleptoparasitism depend- 9 ing on local conditions. -

New Data on the Early Villafranchian Fauna from Vialette (Haute-Loire, France) Based on the Collection of the Crozatier Museum (Le Puy-En-Velay, Haute-Loire, France)

ARTICLE IN PRESS Quaternary International 179 (2008) 64–71 New data on the Early Villafranchian fauna from Vialette (Haute-Loire, France) based on the collection of the Crozatier Museum (Le Puy-en-Velay, Haute-Loire, France) Fre´de´ric Lacombata,Ã, Laura Abbazzib, Marco P. Ferrettib, Bienvenido Martı´nez-Navarroc, Pierre-Elie Moulle´d, Maria-Rita Palomboe, Lorenzo Rookb, Alan Turnerf, Andrea M.-F. Vallig aForschungsstation fu¨r Quata¨rpala¨ontologie Senckenberg, Weimar, Am Jakobskirchhof 4, D-99423 Weimar, Germany bDipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita` di Firenze, Via G. La Pira 4, 50121 Firenze, Italy cICREA, A`rea de Prehisto`ria, Universitat Rovira i Virgili-IPHES, Plac-a Imperial Tarraco 1, 43005 Tarragona, Spain dMuse´e de Pre´histoire Re´gionale de Menton, Rue Lore´dan Larchey, 06500 Menton, France eDipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita` degli Studi di Roma ‘‘La Sapienza’’, CNR, Ple. Aldo Moro, 500185 Roma, Italy fSchool of Biological and Earth Sciences, Liverpool John Moore University, Liverpool L3 3AF, UK g78 rue du pont Guinguet, 03000 Moulins, France Available online 7 September 2007 Abstract Vialette (3.14 Ma), like Sene` ze, Chilhac, Sainzelles, Ceyssaguet or Soleilhac, is one of the historical sites located in Haute-Loire (France). The lacustrine sediments of Vialette are the result of a dammed lake formed by a basalt flow above Oligocene layers, and show a geological setting typical for this area, where many localities are connected with maar structures that have allowed intra-crateric lacustrine deposits to accumulate. Based on previous studies and this work, a faunal list of 17 species of large mammals has been established. -

OPTIMAL FORAGING on the ROOF of the WORLD: a FIELD STUDY of HIMALAYAN LANGURS a Dissertation Submitted to Kent State University

OPTIMAL FORAGING ON THE ROOF OF THE WORLD: A FIELD STUDY OF HIMALAYAN LANGURS A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Kenneth A. Sayers May 2008 Dissertation written by Kenneth A. Sayers B.A., Anderson University, 1996 M.A., Kent State University, 1999 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2008 Approved by ____________________________________, Dr. Marilyn A. Norconk Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee ____________________________________, Dr. C. Owen Lovejoy Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee ____________________________________, Dr. Richard S. Meindl Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee ____________________________________, Dr. Charles R. Menzel Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Accepted by ____________________________________, Dr. Robert V. Dorman Director, School of Biomedical Sciences ____________________________________, Dr. John R. D. Stalvey Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .....................................................................................x Chapter I. PRIMATES AT THE EXTREMES ..................................................1 Introduction: Primates in marginal habitats ......................................1 Prosimii .............................................................................................2 -

Title Notes on Carnivore Fossils from the Pliocene Udunga Fauna

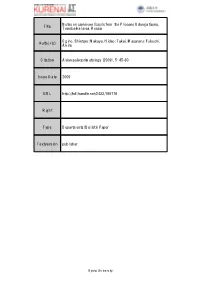

Notes on carnivore fossils from the Pliocene Udunga fauna, Title Transbaikal area, Russia Ogino, Shintaro; Nakaya, Hideo; Takai, Masanaru; Fukuchi, Author(s) Akira Citation Asian paleoprimatology (2009), 5: 45-60 Issue Date 2009 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/199776 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Asian Paleoprimatology, vol. 5: 45-60 (2008) Kyoto University Primate Research Institute Notes on carnivore fossils from the Pliocene Udunga fauna, Transbaikal area, Russia Shintaro Ogino1*, Hideo Nakaya2, Masanaru Takai1, Akira Fukuchi2, 3 1Primate Research Institute, Kyoto University. Inuyama 484-8506, Japan 2Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Kagoshima University, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan 3Graduate School of Natural Science and Technology, Okayama University, Okayama 700-8530, Japan *Corresponding author. e-mail: [email protected] Abstract We provide notes of carnivore fossils from the middle Pliocene Udunga fauna, Transbaikal area, Russia. The fossil carnivore assemblage consists of more than 200 specimens including eleven genera. Ursus, Parailurus, Parameles, and Ferinestrix are representative of the animals of thermophilic forest biotopes. On the other hand, Chasmaporthetes and Pliocrocuta are probably specialized in open environment. The prosperity both in foresal and semiarid carnivores indicate that the Udunga fauna is comprised of mosaic elements. Introduction The fauna dating back to the Pliocene in Udunga, Transbaikalia, Russia, comprises eleven species of mammals, such as rodents, lagomorphs, carnivores, perissodactyls, artiodactyls, and elephants (Kalmykov, 1989, 1992, 2003; Kalmykov and Maschenko, 1992, 1995 Vislobokova et al., 1993, 1995;; Erbajeva et al., 2003). The Udunga site is located on the left bank of the Temnik River, the tributary of the Selenga River in the vicinity of Udunga village (Figure 1).