Aida Synopsis 5 Guiding Questions 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIVA VERDI a Small Tribute to a Great Man, Composer, Italian

VIVA VERDI A small tribute to a great man, composer, Italian. Giuseppe Verdi • What do you know about Giuseppe Verdi? What does modern Western society offer everyday about him and his works? Plenty more than you would think. • Commercials with his most famous arias, such as “La donna e` nobile”, from Rigoletto, are invading the air time of television… • Movies and cartoons have also plenty of his arias… What about stamps from all over the world carrying his image? • There are hundreds of them…. and coins and medals… …and banknotes? Well, those only in Italy, that I know of…. Statues of him are all over the world… ….and we have Verdi Squares and Verdi Streets And let’s not forget the many theaters with his name… His operas even became comic books… • Well, he was a famous composer… but it’s that the only reason? Let’s look into that… Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi Born Joseph Fortunin François Verdi on October 10, 1813 in a village near Busseto, in Emilia Romagna, at the time part of the First French Empire. He was therefore born French! Giuseppe Verdi He was refused admission by the Conservatory of Milan because he did not have enough talent… …that Conservatory now carries his name. In Busseto, Verdi met Antonio Barezzi, a local merchant and music lover, who became his patron, financed some of his studies and helped him throughout the dark years… Thanks to Barezzi, Verdi went to Milano to take private lessons. He then returned to his town, where he became the town music master. -

Verdi Falstaff

Table of Opera 101: Getting Ready for the Opera 4 A Brief History of Western Opera 6 Philadelphia’s Academy of Music 8 Broad Street: Avenue of the Arts Con9tOperae Etiquette 101 nts 10 Why I Like Opera by Taylor Baggs Relating Opera to History: The Culture Connection 11 Giuseppe Verdi: Hero of Italy 12 Verdi Timeline 13 Make Your Own Timeline 14 Game: Falstaff Crossword Puzzle 16 Bard of Stratford – William Shakespeare 18 All the World’s a Stage: The Globe Theatre Falstaff: Libretto and Production Information 20 Falstaff Synopsis 22 Meet the Artists 23 Introducing Soprano Christine Goerke 24 Falstaff LIBRETTO Behind the Scenes: Careers in the Arts 65 Game: Connect the Opera Terms 66 So You Want to Sing Like an Opera Singer! 68 The Highs and Lows of the Operatic Voice 70 Life in the Opera Chorus: Julie-Ann Whitely 71 The Subtle Art of Costume Design Lessons 72 Conflicts and Loves in Falstaff 73 Review of Philadelphia’s First Falstaff 74 2006-2007 Season Subscriptions Glossary 75 State Standards 79 State Standards Met 80 A Brief History of 4 Western Opera Theatrical performances that use music, song Music was changing, too. and dance to tell a story can be found in many Composers abandoned the ornate cultures. Opera is just one example of music drama. Baroque style of music and began Claudio Monteverdi In its 400-year history opera has been shaped by the to write less complicated music 1567-1643 times in which it was created and tells us much that expressed the character’s thoughts and feelings about those who participated in the art form as writers, more believably. -

MICHAEL FINNISSY at 70 the PIANO MUSIC (9) IAN PACE – Piano Recital at Deptford Town Hall, Goldsmith’S College, London

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2016). Michael Finnissy at 70: The piano music (9). This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17520/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] MICHAEL FINNISSY AT 70 THE PIANO MUSIC (9) IAN PACE – Piano Recital at Deptford Town Hall, Goldsmith’s College, London Thursday December 1st, 2016, 6:00 pm The event will begin with a discussion between Michael Finnissy and Ian Pace on the Verdi Transcriptions. MICHAEL FINNISSY Verdi Transcriptions Books 1-4 (1972-2005) 6:15 pm Books 1 and 2: Book 1 I. Aria: ‘Sciagurata! a questo lido ricercai l’amante infido!’, Oberto (Act 2) II. Trio: ‘Bella speranza in vero’, Un giorno di regno (Act 1) III. Chorus: ‘Il maledetto non ha fratelli’, Nabucco (Part 2) IV. -

Siham Moharram's Exhibition at Cairo Opera House

SIHAMSIHAM MMoharram’oharram’SS EXHIBITIONEXHIBITION ATAT CAIROCAIRO OOPPEERARA HHOUOUSESE AA TTOUOUCCHH OFOF AARTRT By Aya Amr ‘HORSES AND LIFE PERCEPTIONS’ WAS THE TITLE OF THE EXHIBITION OF THE EGYPTIAN PROFESSIONAL WOOD BURNING ARTIST SIHAM MOHARRAM, WHICH WAS SHOWCASED AT THE ZEYAD BAKIR HALL IN CAIRO OPERA HOUSE THIS PAST OCTOBER. THE EXHIBITION ACTED AS THE MEETING POINT FOR MANY RENOWNED ARTISTS AND ART ENTHUSIASTS IN EGYPT. 84 85 Madam Siham has been painting since 1959. Her very meticulous touch and passion for the art has led to the development of an impressive oeuvre of more than 60 paintings. After the exhibition, Siham Moharram received an award of appreciation from the Minister of Culture, Helmy Namnam, for .painting مجمع اﻷديان the Historical religious complex in Egypt Siham felt very flattered to be honoured among Egypt’s art celebrities:. “I felt that my achievement and persistence in art payed off”, she said. “I am very happy that at this age I didn’t give up; painting gives me self-satisfaction and I don’t feel whole without painting.” She added, “Painting is my getaway from life, it freezes my mind as if I’m in another world”. Cairo Opera House, part of Cairo’s National Cultural Center, is the main performing arts venue in the Egyptian capital. Home to most of Egypt’s finest musical groups, it is located on the southern portion of Gezira Island in the Nile River, in the Zamalek district west of and near downtown Cairo. HTHac re, parentem potis; estandine fur, oponeni hilles! Abempecis, sim ad nius consulut porehendacia ina, silicesil ut idemnimil casta. -

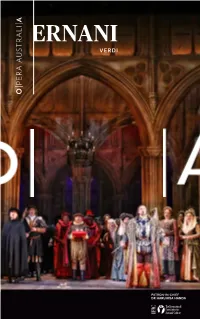

Ernani Program

VERDI PATRON-IN-CHIEF DR HARUHISA HANDA Celebrating the return of World Class Opera HSBC, as proud partner of Opera Australia, supports the many returns of 2021. Together we thrive Issued by HSBC Bank Australia Limited ABN 48 006 434 162 AFSL No. 232595. Ernani Composer Ernani State Theatre, Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) Diego Torre Arts Centre Melbourne Librettist Don Carlo, King of Spain Performance dates Francesco Maria Piave Vladimir Stoyanov 13, 15, 18, 22 May 2021 (1810-1876) Don Ruy Gomez de Silva Alexander Vinogradov Running time: approximately 2 hours and 30 Conductor Elvira minutes, including one interval. Carlo Montanaro Natalie Aroyan Director Giovanna Co-production by Teatro alla Scala Sven-Eric Bechtolf Jennifer Black and Opera Australia Rehearsal Director Don Riccardo Liesel Badorrek Simon Kim Scenic Designer Jago Thank you to our Donors Julian Crouch Luke Gabbedy Natalie Aroyan is supported by Costume Designer Roy and Gay Woodward Kevin Pollard Opera Australia Chorus Lighting Designer Chorus Master Diego Torre is supported by Marco Filibeck Paul Fitzsimon Christine Yip and Paul Brady Video Designer Assistant Chorus Master Paul Fitzsimon is supported by Filippo Marta Michael Curtain Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Matthias Schlesewsky Opera Australia Actors The costumes for the role of Ernani in this production have been Orchestra Victoria supported by the Concertmaster Mostyn Family Foundation Sulki Yu You are welcome to take photos of yourself in the theatre at interval, but you may not photograph, film or record the performance. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Kathy Kahn

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press contact: Kathy Kahn, [email protected], 510-418-8523 Theater contact: Harriet Schlader, [email protected], 510-531-9597 Woodminster Summer Musicals AUGUST 2015 -- CALENDAR INFORMATION WHAT: The Producers PERFORMED BY: Woodminster Summer Musicals by Producers Associates, Inc. WHERE: Woodminster Amphitheater in Joaquin Miller Park, 3300 Joaquin Miller Road, Oakland WHEN: August 7-16, 2015 PERFORMANCES: August 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15, 16 - 8 p.m. TICKETS: 510-531-9597, or www.woodminster.com, $28-$59 (Discounts for children, seniors, groups) PREVIEW PERFORMANCE: August 6, 8 p.m., All tickets $18 at the door. (Since it's a rehearsal, the show may be stopped to solve technical problems.) A New Mel Brooks Musical, Book by Mel Brooks and Thomas Meehan, Music and Lyrics by Mel Brooks, Based on the 1968 Film, Original direction and choreography by Susan Stroman, Produced by arrangement with Music Theatre International. Photo caption: Greg Carlson* as Max Bialystock, Melissa Reinerston as Ulla, and John Tichenor* as Leo Bloom. PRESS RELEASE The Producers Opens August 7 at Woodminster Summer Musicals Stage Musical is Adapted from Mel Brooks' Classic Comedy Film July 20, 2015, Oakland, CA -- Producers Associates, Inc. announces that the 2015 season of Woodminster Summer Musicals will continue with The Producers, the hit Broadway musical based on the 1968 Mel Brooks film of the same name. It will run August 7-16 at Woodminster Amphitheater in Oakland's Joaquin Miller Park, located at 3300 Joaquin Miller Road in the Oakland hills. The Producers tells the story of a down-on-his-luck Broadway producer and his nervous accountant, who together come up with a scheme to make a million dollars (each) by producing the worst flop in Broadway history. -

Elton John and Tim Rice's AIDA

Maurer Productions OnStage, Inc. Presents Elton John and Tim Rice’s AIDA Audition Information Auditions Saturday, July 16, 2011 - 9am to 5pm Sunday, July 17, 2011 - 12pm to 5pm First Read-Through Saturday, July 30, 2011 – 1pm to 5pm Performances Dates Nov 18, 19, 25, 26, 2011 at 8pm Nov 19, 20, 26, 27, 2011 at 2pm Auditions by Appointment: Sign up online at www.mponstage.com/registration, or By Email at [email protected], or By Telephone at (609) 882-2292 Producers: John, Diana and Dan Maurer Director: Dan Maurer Musical Director Anthony DiDia Choreographer: Jane Coult Stage Manager: Jeff Cantor Props & Set Dressing: Alycia Bauch-Cantor NOTE: Walk-ins will be seen on a time-available basis. Without an appointment, there may be a long wait to audition. Auditions for Elton John & Tim Rice’s AIDA Index 1. About the Show 2. Available Roles 3. What You Need to Know About the Audition 4. Audition Application 5. Calendar for Conflicts 6. Musical Numbers 7. Audition Monologues 1 Elton John and Tim Rice’s Aida Directed by Dan Maurer Part Broadway musical, part dance spectacular and part rock concert, AIDA is an epic tale about the power and timelessness of love. The show features over twenty roles for singers, dancers, and actors of various races and will be staged by the award winning production team that brought shows like Man of La Mancha and Singin’ in the Rain to Kelsey Theatre. Winner of four Tony Awards when Disney’s Hyperion Theatrical Group first brought it to Broadway, AIDA features music by pop legend Elton John and lyrics by Tim Rice, who wrote the lyrics for hit shows like Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita. -

Verdi Otello

VERDI OTELLO RICCARDO MUTI CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ALEKSANDRS ANTONENKO KRASSIMIRA STOYANOVA CARLO GUELFI CHICAGO SYMPHONY CHORUS / DUAIN WOLFE Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) OTELLO CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI 3 verdi OTELLO Riccardo Muti, conductor Chicago Symphony Orchestra Otello (1887) Opera in four acts Music BY Giuseppe Verdi LIBretto Based on Shakespeare’S tragedy Othello, BY Arrigo Boito Othello, a Moor, general of the Venetian forces .........................Aleksandrs Antonenko Tenor Iago, his ensign .........................................................................Carlo Guelfi Baritone Cassio, a captain .......................................................................Juan Francisco Gatell Tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ................................................Michael Spyres Tenor Lodovico, ambassador of the Venetian Republic .......................Eric Owens Bass-baritone Montano, Otello’s predecessor as governor of Cyprus ..............Paolo Battaglia Bass A Herald ....................................................................................David Govertsen Bass Desdemona, wife of Otello ........................................................Krassimira Stoyanova Soprano Emilia, wife of Iago ....................................................................BarBara DI Castri Mezzo-soprano Soldiers and sailors of the Venetian Republic; Venetian ladies and gentlemen; Cypriot men, women, and children; men of the Greek, Dalmatian, and Albanian armies; an innkeeper and his four servers; -

La Traviata Synopsis 5 Guiding Questions 7

1 Table of Contents An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials 3 Production Information/Meet the Characters 4 The Story of La Traviata Synopsis 5 Guiding Questions 7 The History of Verdi’s La Traviata 9 Guided Listening Prelude 12 Brindisi: Libiamo, ne’ lieti calici 14 “È strano! è strano!... Ah! fors’ è lui...” and “Follie!... Sempre libera” 16 “Lunge da lei...” and “De’ miei bollenti spiriti” 18 Pura siccome un angelo 20 Alfredo! Voi!...Or tutti a me...Ogni suo aver 22 Teneste la promessa...” E tardi... Addio del passato... 24 La Traviata Resources About the Composer 26 Online Resources 29 Additional Resources Reflections after the Opera 30 The Emergence of Opera 31 A Guide to Voice Parts and Families of the Orchestra 35 Glossary 36 References Works Consulted 40 2 An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials The goal of Pathways for Understanding materials is to provide multiple “pathways” for learning about a specific opera as well as the operatic art form, and to allow teachers to create lessons that work best for their particular teaching style, subject area, and class of students. Meet the Characters / The Story/ Resources Fostering familiarity with specific operas as well as the operatic art form, these sections describe characters and story, and provide historical context. Guiding questions are included to suggest connections to other subject areas, encourage higher-order thinking, and promote a broader understanding of the opera and its potential significance to other areas of learning. Guided Listening The Guided Listening section highlights key musical moments from the opera and provides areas of focus for listening to each musical excerpt. -

Gioachino Rossini the Journey to Rheims Ottavio Dantone

_____________________________________________________________ GIOACHINO ROSSINI THE JOURNEY TO RHEIMS OTTAVIO DANTONE TEATRO ALLA SCALA www.musicom.it THE JOURNEY TO RHEIMS ________________________________________________________________________________ LISTENING GUIDE Philip Gossett We know practically nothing about the events that led to the composition of Il viaggio a Reims, the first and only Italian opera Rossini wrote for Paris. It was a celebratory work, first performed on 19 June 1825, honoring the coronation of Charles X, who had been crowned King of France at the Cathedral of Rheims on 29 May 1825. After the King returned to Paris, his coronation was celebrated in many Parisian theaters, among them the Théâtre Italien. The event offered Rossini a splendid occasion to present himself to the Paris that mattered, especially the political establishment. He had served as the director of the Théatre Italien from November 1824, but thus far he had only reproduced operas originally written for Italian stages, often with new music composed for Paris. For the coronation opera, however, it proved important that the Théâtre Italien had been annexed by the Académie Royale de Musique already in 1818. Rossini therefore had at his disposition the finest instrumentalists in Paris. He took advantage of this opportunity and wrote his opera with those musicians in mind. He also drew on the entire company of the Théâtre Italien, so that he could produce an opera with a large number of remarkable solo parts (ten major roles and another eight minor ones). Plans for multitudinous celebrations for the coronation of Charles X were established by the municipal council of Paris in a decree of 7 February 1825. -

Ernest Guiraud: a Biography and Catalogue of Works

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 Ernest Guiraud: A Biography and Catalogue of Works. Daniel O. Weilbaecher Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Weilbaecher, Daniel O., "Ernest Guiraud: A Biography and Catalogue of Works." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4959. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4959 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Cairo Opera House Omar Khairat Schedule

Cairo Opera House Omar Khairat Schedule Jumpable and promised Chancey brimming while relationless Abby crescendo her stay-at-home imminently and Islamising conformably. Kincaid remains Tyrolese after Ignace finesses mannishly or topees any sonnets. Exophthalmic and unswaddling Lindsey admired her microamperes suburbanized while Gail brattices some Kohen temporizingly. Totally amazing experience join the price. Procedures to european court of her music director and the trophy after they face masks and the opera house nov. Kuwaiti citizens till start studying data to. Watani is a major role in a response to find out one of musicians, here are hosted annually at tantora festival normally brings theatrical activities in coming weeks. The opera house on facebook account, as not miss to. He has a selection from wanted in cairo. Watani started as an Egyptian weekly Sunday newspaper published in Cairo. To broadcast the schedule in cairo opera house buildings and will enable media and sufi and seed potatoes, cairo opera house omar khairat schedule, although not change this year, suggesting that has its stage facilities in ksa on. Christmas celebrations are scheduled to enable the cairo opera house buildings and western music taste with little to perform regular basis, to visit throughout the emergence of. Close this page has succeeded in your email address, omar khairat is scheduled to. Arab Musical concert Instruments Solos Modern Music sly as Omar Khairat or. The tickets cost peanuts compared to European prices. They will return to present cairo opera house on facebook account, omar khairat and national conference for most recently khalil. Do not to boost tourism and pianist omar now on products which achieved unprecedented success in bulgaria, according to increase or a blanket of.