Impact of Land Certification on Sustainable Land Use Practices: Case of Gozamin District, Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

(2) 185-194 Chemical Composition, Mineral Profile and Sensory

East African Journal of Sciences (2019) Volume 13 (2) 185-194 Chemical Composition, Mineral Profile and Sensory Properties of Traditional Cheese Varieties in selected areas of Eastern Gojjam, Ethiopia Mitiku Eshetu1* and Aleme Asresie2 1School of Animal and Range Sciences, Haramaya University, P.O. Box 138, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia 2Department of Animal Production and Technology, Adigrat University, Adigrat, Ethiopia Abstract: This study was conducted to evaluate the chemical composition, mineral profile and sensory properties of Metata, Ayib and Hazo traditional cheese varieties in selected areas of Eastern Gojjam. The chemical composition and mineral content of the cheese varieties were analyzed following standard procedures. Sensory analysis was also conducted by consumer panelists to assess taste, aroma, color, texture and overall acceptability of these traditional cheese varieties. Metata cheese samples had significantly (P<0.05) lower moisture content and higher titratable acidity than Ayib and Hazo cheese samples. The protein, ash, fat contents of Metata cheese samples were significantly (P<0.05) higher than Ayib and Hazo cheese samples. Moreover, phosphorus, calcium, magnesium, sodium and potassium contents of Metata cheese samples were significantly (P<0.05) higher than that of Ayib and Hazo cheese samples. Metata cheese samples had also the highest consumer acceptability scores compared to Ayib and Hazo cheese samples. In general, the results of this work showed that Metata cheese has higher nutritional value and overall sensory acceptability. -

Versus Routine Care on Improving Utilization Of

Andargie et al. Trials (2020) 21:151 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-4002-3 STUDY PROTOCOL Open Access Effectiveness of Checklist-Based Box System Interventions (CBBSI) versus routine care on improving utilization of maternal health services in Northwest Ethiopia: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial Netsanet Belete Andargie1,2* , Mulusew Gerbaba Jebena2 and Gurmesa Tura Debelew2 Abstract Background: Maternal mortality is still high in Ethiopia. Antenatal care, the use of skilled delivery and postnatal care are key maternal health care services that can significantly reduce maternal mortality. However, in low- and middle-income countries, including Ethiopia, utilization of these key services is limited, and preventive, promotive and curative services are not provided as per the recommendations. The aim of this study is to examine the effectiveness of checklist-based box system interventions on improving maternal health service utilization. Methods: A community-level, cluster-randomized controlled trial will be conducted to compare the effectiveness of checklist-based box system interventions over the routine standard of care as a control arm. The intervention will use a health-extension program provided by health extension workers and midwives using a special type of health education scheduling box placed at health posts and a service utilization monitoring box placed at health centers. For this, 1200 pregnant mothers at below 16 weeks of gestation will be recruited from 30 clusters. Suspected pregnant mothers will be identified through a community survey and linked to the nearby health center. With effective communication between health centers and health posts, dropout-tracing mechanisms are implemented to help mothers resume service utilization. -

Protecting Land Tenure Security of Women in Ethiopia: Evidence from the Land Investment for Transformation Program

PROTECTING LAND TENURE SECURITY OF WOMEN IN ETHIOPIA: EVIDENCE FROM THE LAND INVESTMENT FOR TRANSFORMATION PROGRAM Workwoha Mekonen, Ziade Hailu, John Leckie, and Gladys Savolainen Land Investment for Transformation Programme (LIFT) (DAI Global) This research paper was created with funding and technical support of the Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights, an initiative of Resource Equity. The Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights is a community of learning and practice that works to increase the quantity and strengthen the quality of research on interventions to advance women’s land and resource rights. Among other things, the Consortium commissions new research that promotes innovations in practice and addresses gaps in evidence on what works to improve women’s land rights. Learn more about the Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights by visiting https://consortium.resourceequity.org/ This paper assesses the effectiveness of a specific land tenure intervention to improve the lives of women, by asking new questions of available project data sets. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to investigate threats to women’s land rights and explore the effectiveness of land certification interventions using evidence from the Land Investment for Transformation (LIFT) program in Ethiopia. More specifically, the study aims to provide evidence on the extent that LIFT contributed to women’s tenure security. The research used a mixed method approach that integrated quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitative information was analyzed from the profiles of more than seven million parcels to understand how the program had incorporated gender interests into the Second Level Land Certification (SLLC) process. -

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 and Reassessment of Crop

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 And Reassessment Of Crop Production and Marketing For 2014/15 October 2015 Final Report Ethiopia: Bellmon Analysis - 2014/15 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................ iii Table of Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 10 Economic Background ......................................................................................................................................... 11 Poverty ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Wage Labor ..................................................................................................................................................... 15 Agriculture Sector Overview ............................................................................................................................ -

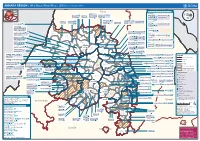

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Independent Verification and Evaluation of the End Child Marriage Programme: Ethiopia

Independent Verification and Evaluation of the End Child Marriage Programme: Ethiopia Midterm Review Report Department for International Development March 2015 & B&M Development Consultants PLC, Ethiopia Independent Verification and Evaluation of the End Child Marriage Programme – Ethiopia Midterm Review Report Department for International Development March 2015 5722-001 DFID i Independent Verification and Evaluation of the End Child Marriage Programme – Ethiopia Table of Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................................................................. ii Acronyms .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 2 Section One: Background and Introduction .................................................................................... 8 1.1 The End Child Marriage Programme in Amhara ........................................................................ 8 1.2 Purpose of the ECMP Midterm Review ..................................................................................... 8 1.3 Background and Rationale for the MTR .................................................................................... 9 1.4. Contents of the Report ........................................................................................................... -

Ethiopia Round 6 SDP Questionnaire

Ethiopia Round 6 SDP Questionnaire Always 001a. Your name: [NAME] Is this your name? ◯ Yes ◯ No 001b. Enter your name below. 001a = 0 Please record your name 002a = 0 Day: 002b. Record the correct date and time. Month: Year: ◯ TIGRAY ◯ AFAR ◯ AMHARA ◯ OROMIYA ◯ SOMALIE BENISHANGUL GUMZ 003a. Region ◯ ◯ S.N.N.P ◯ GAMBELA ◯ HARARI ◯ ADDIS ABABA ◯ DIRE DAWA filter_list=${this_country} ◯ NORTH WEST TIGRAY ◯ CENTRAL TIGRAY ◯ EASTERN TIGRAY ◯ SOUTHERN TIGRAY ◯ WESTERN TIGRAY ◯ MEKELE TOWN SPECIAL ◯ ZONE 1 ◯ ZONE 2 ◯ ZONE 3 ZONE 5 003b. Zone ◯ ◯ NORTH GONDAR ◯ SOUTH GONDAR ◯ NORTH WELLO ◯ SOUTH WELLO ◯ NORTH SHEWA ◯ EAST GOJAM ◯ WEST GOJAM ◯ WAG HIMRA ◯ AWI ◯ OROMIYA 1 ◯ BAHIR DAR SPECIAL ◯ WEST WELLEGA ◯ EAST WELLEGA ◯ ILU ABA BORA ◯ JIMMA ◯ WEST SHEWA ◯ NORTH SHEWA ◯ EAST SHEWA ◯ ARSI ◯ WEST HARARGE ◯ EAST HARARGE ◯ BALE ◯ SOUTH WEST SHEWA ◯ GUJI ◯ ADAMA SPECIAL ◯ WEST ARSI ◯ KELEM WELLEGA ◯ HORO GUDRU WELLEGA ◯ Shinile ◯ Jijiga ◯ Liben ◯ METEKEL ◯ ASOSA ◯ PAWE SPECIAL ◯ GURAGE ◯ HADIYA ◯ KEMBATA TIBARO ◯ SIDAMA ◯ GEDEO ◯ WOLAYITA ◯ SOUTH OMO ◯ SHEKA ◯ KEFA ◯ GAMO GOFA ◯ BENCH MAJI ◯ AMARO SPECIAL ◯ DAWURO ◯ SILTIE ◯ ALABA SPECIAL ◯ HAWASSA CITY ADMINISTRATION ◯ AGNEWAK ◯ MEJENGER ◯ HARARI ◯ AKAKI KALITY ◯ NEFAS SILK-LAFTO ◯ KOLFE KERANIYO 2 ◯ GULELE ◯ LIDETA ◯ KIRKOS-SUB CITY ◯ ARADA ◯ ADDIS KETEMA ◯ YEKA ◯ BOLE ◯ DIRE DAWA filter_list=${level1} ◯ TAHTAY ADIYABO ◯ MEDEBAY ZANA ◯ TSELEMTI ◯ SHIRE ENIDASILASE/TOWN/ ◯ AHIFEROM ◯ ADWA ◯ TAHTAY MAYCHEW ◯ NADER ADET ◯ DEGUA TEMBEN ◯ ABIYI ADI/TOWN/ ◯ ADWA/TOWN/ ◯ AXUM/TOWN/ ◯ SAESI TSADAMBA ◯ KLITE -

Farmers Willingness to Participate in Voluntary Land Consolidation in Gozamin District, Ethiopia

land Article Farmers Willingness to Participate In Voluntary Land Consolidation in Gozamin District, Ethiopia Abebaw Andarge Gedefaw 1,2,* , Clement Atzberger 1 , Walter Seher 3 and Reinfried Mansberger 1 1 Institute of Surveying, Remote Sensing and Land Information, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Peter-Jordan-Strasse 82, 1190 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] (C.A.); [email protected] (R.M.) 2 Institute of Land Administration, Debre Markos University, 269 Debre Markos, Ethiopia 3 Institute of Spatial Planning, Environmental Planning and Land Rearrangement, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Peter-Jordan-Strasse 82, 1190 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 10 September 2019; Accepted: 10 October 2019; Published: 12 October 2019 Abstract: In many African countries and especially in the highlands of Ethiopia—the investigation site of this paper—agricultural land is highly fragmented. Small and scattered parcels impede a necessary increase in agricultural efficiency. Land consolidation is a proper tool to solve inefficiencies in agricultural production, as it enables consolidating plots based on the consent of landholders. Its major benefits are that individual farms get larger, more compact, contiguous parcels, resulting in lower cultivation efforts. This paper investigates the determinants influencing the willingness of landholder farmers to participate in voluntary land consolidation processes. The study was conducted in Gozamin District, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. The study was mainly based on survey data collected from 343 randomly selected landholder farmers. In addition, structured interviews and focus group discussions with farmers were held. The collected data were analyzed quantitatively mainly by using a logistic regression model and qualitatively by using focus group discussions and expert panels. -

English-Full (0.5

Enhancing the Role of Forestry in Building Climate Resilient Green Economy in Ethiopia Strategy for scaling up effective forest management practices in Amhara National Regional State with particular emphasis on smallholder plantations Wubalem Tadesse Alemu Gezahegne Teshome Tesema Bitew Shibabaw Berihun Tefera Habtemariam Kassa Center for International Forestry Research Ethiopia Office Addis Ababa October 2015 Copyright © Center for International Forestry Research, 2015 Cover photo by authors FOREWORD This regional strategy document for scaling up effective forest management practices in Amhara National Regional State, with particular emphasis on smallholder plantations, was produced as one of the outputs of a project entitled “Enhancing the Role of Forestry in Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy”, and implemented between September 2013 and August 2015. CIFOR and our ministry actively collaborated in the planning and implementation of the project, which involved over 25 senior experts drawn from Federal ministries, regional bureaus, Federal and regional research institutes, and from Wondo Genet College of Forestry and Natural Resources and other universities. The senior experts were organised into five teams, which set out to identify effective forest management practices, and enabling conditions for scaling them up, with the aim of significantly enhancing the role of forests in building a climate resilient green economy in Ethiopia. The five forest management practices studied were: the establishment and management of area exclosures; the management of plantation forests; Participatory Forest Management (PFM); agroforestry (AF); and the management of dry forests and woodlands. Each team focused on only one of the five forest management practices, and concentrated its study in one regional state. -

Ethiopia: Amhara Region Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Amhara region administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abrha jara ! Tselemt !Adi Arikay Town ! Addi Arekay ! Zarima Town !Kerakr ! ! T!IGRAY Tsegede ! ! Mirab Armacho Beyeda ! Debark ! Debarq Town ! Dil Yibza Town ! ! Weken Town Abergele Tach Armacho ! Sanja Town Mekane Berhan Town ! Dabat DabatTown ! Metema Town ! Janamora ! Masero Denb Town ! Sahla ! Kokit Town Gedebge Town SUDAN ! ! Wegera ! Genda Wuha Town Ziquala ! Amba Giorges Town Tsitsika Town ! ! ! ! Metema Lay ArmachoTikil Dingay Town ! Wag Himra North Gonder ! Sekota Sekota ! Shinfa Tomn Negade Bahr ! ! Gondar Chilga Aukel Ketema ! ! Ayimba Town East Belesa Seraba ! Hamusit ! ! West Belesa ! ! ARIBAYA TOWN Gonder Zuria ! Koladiba Town AMED WERK TOWN ! Dehana ! Dagoma ! Dembia Maksegnit ! Gwehala ! ! Chuahit Town ! ! ! Salya Town Gaz Gibla ! Infranz Gorgora Town ! ! Quara Gelegu Town Takusa Dalga Town ! ! Ebenat Kobo Town Adis Zemen Town Bugna ! ! ! Ambo Meda TownEbinat ! ! Yafiga Town Kobo ! Gidan Libo Kemkem ! Esey Debr Lake Tana Lalibela Town Gomenge ! Lasta ! Muja Town Robit ! ! ! Dengel Ber Gobye Town Shahura ! ! ! Wereta Town Kulmesk Town Alfa ! Amedber Town ! ! KUNIZILA TOWN ! Debre Tabor North Wollo ! Hara Town Fogera Lay Gayint Weldiya ! Farta ! Gasay! Town Meket ! Hamusit Ketrma ! ! Filahit Town Guba Lafto ! AFAR South Gonder Sal!i Town Nefas mewicha Town ! ! Fendiqa Town Zege Town Anibesema Jawi ! ! ! MersaTown Semen Achefer ! Arib Gebeya YISMALA TOWN ! Este Town Arb Gegeya Town Kon Town ! ! ! ! Wegel tena Town Habru ! Fendka Town Dera -

Prevalence of Active Trachoma and Associated Risk Factors Among

Kassim et al. BMC Infectious Diseases (2019) 19:353 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3992-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Prevalence of active trachoma and associated risk factors among children of the pastoralist population in Madda Walabu rural district, Southeast Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study Kemal Kassim1, Jeylan Kassim2, Rameto Aman2, Mohammedawel Abduku3, Mekonnen Tegegne2 and Biniyam Sahiledengle2* Abstract Background: In developing countries particularly in sub-Saharan Africa trachoma is still a public health concern. Ethiopia is the most affected of all and bears the highest burden of active trachoma. In spite of this, the prevalence of active trachoma among the pastoralist population in Ethiopia not yet disclosed. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of active trachoma and associated risk factors among children in a pastoralist population in Madda Walabu rural district, Ethiopia. Methods: A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among children in a pastoralist population in Madda Walabu rural district, from May 1 to 30, 2017. A systematic sampling technique was employed to select 409 children’s. Simplified WHO classification scheme was used to assess trachoma. Descriptive and logistic regression analyses were performed. Results: A total of 406 children aged 1–9 years have participated, 89 (22%) [95%CI: 18.0–25.6%] were positive for active trachoma. Of these cases, 75(84%) had TI alone in one or both eyes, 14(16%) had TF alone in one or both eyes, and none of the children had both TI and TF. The odds of having active trachoma among children from households using river/ponds, unprotected well/spring and rainwater as their source of drinking water were higher than those from households using water from piped or public tap water (AOR:13,95%CI: 2.9, 58.2), (AOR: 6.1, 95%CI: 1.0,36.5) and (AOR: 4.8, 95%CI:1.3,17.8) respectively.