UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lntertextuality in AMERICAN DRAMA Critical Essays on Eugene 0 'Neill, Susan Glaspell, Thornton Wilder, -~Arthur Miller and Other Playwrights

lNTERTEXTUALITY IN AMERICAN DRAMA Critical Essays on Eugene 0 'Neill, Susan Glaspell, Thornton Wilder, -~Arthur Miller and Other Playwrights Edited by Drew Eisenhauer and Brenda Murphy McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London Table of Contents Introduction: What Is "'ntertextuality" and Why Is the Term Important Today? DREW EISENHAUER .......................... 1 Part I: Literary Intertextuality LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA SECTION ONE: PoETS Intertextuality in American drama : critical essays on Eugene O'Neill, Susan Glaspell, Thornton Wilder, Arthur Miller The Ancient Mariner and O'Neill's Intertextual Epiphany and other playwrights I edited by Drew Eisenhauer and (Herman Daniel Farrell III) ............................... 10 Brenda Murphy. p. em. "Deep in my silent sea": Eugene O'Neill's Extended Includes bibliographical references and index. Adaptation of Coleridge's The Ancient Mariner ISBN 978-0-7864-6391-6 (Rupendra Guha Majumdar) ............................... 25 softcover : acid free paper § A Multi-Faceted Moon: Shakespearean and Keatsian Echoes 1. American drama- 20th century- History in Eugene O'Neill's A Moon for the Misbegotten and criticism. 2. O'Neill, Eugene, 1888-1953- (Aurelie Sanchez) ........................................ 36 Criticism and interpretation. 3. Glaspell, Susan, 1876-1948- Criticism and interpretation. Trailing Clouds of Glory: Glaspell, Romantic Ideology 4. Wilder, Thornton, 1897-1975- Criticism and Cultural Conflict in Modern American Literature and interpretation. 5. Miller, Arthur, 1915-2005- Criticism and interpretation. 6. Intertextuality. (Michael Winetsky) ...................................... 52 I. Eisenhauer, Drew. II. Murphy, Brenda, 1950- On Closets and Graves: Intertextualities in Susan Glaspell's PS350.I58 2013 Alison's House and Emily Dickinson's Poetry 812'.509-dc23 2012038662 (Noelia Hernando-Real) ................................. -

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

Our-Town-Study-Guide.Pdf

STUDY GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PERFORMANCE INFORMATION PAGE 3 TORNTON WILDER PAGE 4 THORNTON WILDER CHRONOLOGY PAGE 5 OUR TOWN: A BRIEF HISTORY PAGE 6 PLAY SYNOPSIS PAGE 7 CAST OF CHARACTERS PAGE 10 THE PULITZER PRIZE PAGE 11 OUR TOWN: A HISTORICAL TIMELINE PAGE 12 THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGING PAGE 16 THEMES OF OUR TOWN PAGE 17 NEW HAMPSHIRE PAGE 18 SCENIC DESIGN PAGE 19 PROMPTS FOR DISCUSSION PAGE 21 AUDIENCE ETIQUETTE PAGE 22 STUDENT EVALUATION PAGE 23 TEACHER EVALUATION PAGE 24 New Stage Theatre Presents OUR TOWN by Thornton Wilder Directed by Francine Thomas Reynolds Sponsored by Sanderson Farms Stage Manager Lighting Designer Scenic Designer Elise McDonald Brent Lefavor Dex Edwards Costume Designer Technical Director/Properties Lesley Raybon Richard Lawrence There will be one 10-minute intermission THE CAST Cast (in order of appearance) STAGE MANAGER Sharon Miles DR. GIBBS Larry Wells HOWIE NEWSOME Christan McLaurine JOE CROWELL, JR. Ben Sanders MRS. GIBBS Malaika Quarterman MRS. WEBB Kerri Sanders GEORGE GIBBS Cliff Miller * REBECCA GIBBS Mary Frances Dean WALLY WEBB Jeffrey Cornelius EMILY WEBB Devon Caraway* PROFESSOR WILLARD Amanda Dear MR. WEBB Yohance Myles* WOMAN #1 LaSharron Purvis SIMON STIMSON Jeff Raab WOMAN #2 Hope Prybylski WOMAN #3 Ashanti Alexander CONSTABLE WARREN Chris Roebuck MRS. SOAMES Joy Amerson SI CROWELL Alex Forbes SAM CRAIG Jake Bell JOE STODDARD James Anderson FARMER MCCARTY Peter James VIOLINIST Miranda Kunk *The actor appears through the courtesy of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Profes- sional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. THORNTON WILDER Thornton Wilder was born in Madison, Wisconsin on April 17, 1897. -

Plays to Read for Furman Theatre Arts Majors

1 PLAYS TO READ FOR FURMAN THEATRE ARTS MAJORS Aeschylus Agamemnon Greek 458 BCE Euripides Medea Greek 431 BCE Sophocles Oedipus Rex Greek 429 BCE Aristophanes Lysistrata Greek 411 BCE Terence The Brothers Roman 160 BCE Kan-ami Matsukaze Japanese c 1300 anonymous Everyman Medieval 1495 Wakefield master The Second Shepherds' Play Medieval c 1500 Shakespeare, William Hamlet Elizabethan 1599 Shakespeare, William Twelfth Night Elizabethan 1601 Marlowe, Christopher Doctor Faustus Jacobean 1604 Jonson, Ben Volpone Jacobean 1606 Webster, John The Duchess of Malfi Jacobean 1612 Calderon, Pedro Life is a Dream Spanish Golden Age 1635 Moliere Tartuffe French Neoclassicism 1664 Wycherley, William The Country Wife Restoration 1675 Racine, Jean Baptiste Phedra French Neoclassicism 1677 Centlivre, Susanna A Bold Stroke for a Wife English 18th century 1717 Goldoni, Carlo The Servant of Two Masters Italian 18th century 1753 Gogol, Nikolai The Inspector General Russian 1842 Ibsen, Henrik A Doll's House Modern 1879 Strindberg, August Miss Julie Modern 1888 Shaw, George Bernard Mrs. Warren's Profession Modern Irish 1893 Wilde, Oscar The Importance of Being Earnest Modern Irish 1895 Chekhov, Anton The Cherry Orchard Russian 1904 Pirandello, Luigi Six Characters in Search of an Author Italian 20th century 1921 Wilder, Thorton Our Town Modern 1938 Brecht, Bertolt Mother Courage and Her Children Epic Theatre 1939 Rodgers, Richard & Oscar Hammerstein Oklahoma! Musical 1943 Sartre, Jean-Paul No Exit Anti-realism 1944 Williams, Tennessee The Glass Menagerie Modern -

Hair for Rent: How the Idioms of Rock 'N' Roll Are Spoken Through the Melodic Language of Two Rock Musicals

HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Eryn Stark August, 2015 HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS Eryn Stark Thesis Approved: Accepted: _____________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Nikola Resanovic Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Interim Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Rex Ramsier _______________________________ _______________________________ Department Chair or School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY ...............................................................................3 A History of the Rock Musical: Defining A Generation .........................................3 Hair-brained ...............................................................................................12 IndiffeRent .................................................................................................16 III. EDITORIAL METHOD ..............................................................................................20 -

The Lived Experiences of Our Community: Stories & Data From

The Lived Experiences of Our Community: Stories & Data from Needham, MA September 2020 Updated Version (10.23.20) Submitted by The Lived Experiences Project, Needham, MA Acknowledgments The Lived Experiences Project (LEP) would like to gratefully acknowledge the time and emotional effort invested by every LEP survey respondent to date. Thank you for entrusting us with your stories, but also for exhibiting courage and resilience, and for speaking up to make our town a place of belonging and equity. We hear you. We see you. Additionally, LEP would like to thank the Needham High School alumni network for offering their survey data for inclusion in this analysis. LEP is also grateful to the Needham Diversity Initiative and Equal Justice in Needham for their survey respondent outreach, and to Over Zero, a nonprofit in Washington DC that works with communities to build resilience to identity-based violence, for its encouragement and support. This report was conceived, researched and written by local residents of diverse backgrounds and disciplines who wish to see their town become a true home of inclusion and equity. Dr. Nichole Argo served as the report’s primary author (and takes full responsibility for any errors within), with support from Sophie Schaffer, who cleaned and organized the survey data, and Lauren Mullady, who helped to produce data visualizations. The report was reviewed by The Lived Experiences Project (LEP) Review Committee, which provided feedback on the write-up as well as earlier input on the survey design input and methodology. The Review Committee includes: Caitryn Lynch (anthropology), Lakshmi Balachandra (economics), Smriti Rao (economics), Rebecca Young (social work), Jenn Scheck-Kahn (writing), Christina Matthews (public health), Beth Pinals (education), and Anna Giraldo-Kerr (inclusive leadership). -

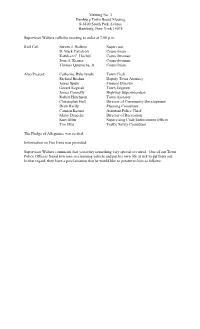

Meeting No. 3 Hamburg Town Board Meeting S-6100 South Park Avenue Hamburg, New York 14075

Meeting No. 3 Hamburg Town Board Meeting S-6100 South Park Avenue Hamburg, New York 14075 Supervisor Walters calls the meeting to order at 7:00 p.m. Roll Call: Steven J. Walters Supervisor D. Mark Cavalcoli Councilman Kathleen C. Hochul Councilwoman Joan A. Kesner Councilwoman Thomas Quatroche, Jr. Councilman Also Present: Catherine Rybczynski Town Clerk Richard Boehm Deputy Town Attorney James Spute Finance Director Gerard Kapsiak Town Engineer James Connolly Highway Superintendent Robert Hutchison Town Assessor Christopher Hull Director of Community Development Drew Reilly Planning Consultant Carmen Kesner Assistant Police Chief Marty Denecke Director of Recreation Kurt Allen Supervising Code Enforcement Officer Tim Ellis Traffic Safety Consultant The Pledge of Allegiance was recited. Information on Fire Exits was provided. Supervisor Walters comments that yesterday something very special occurred. One of our Town Police Officers found two men in a burning vehicle and put his own life at risk to get them out. In that regard, they have a proclamation that he would like to present to him as follows: Councilwoman Hochul comments that the Town was awarded by Sports Illustrated as a “Good Sports Community” finalist out of 1,300 communities that submitted nominations for this award. The Town of Hamburg came in the top seventeen and that is an incredible tribute to our Recreation Department and Mr. Denecke and his incredible team of professionals and Councilman Quatroche, who was the liaison up until this past January when she took over. 7:00 p.m. Public Hearing for an amendment to said Zoning Code for properties located at 4962 South Park Avenue; 4954 South Park Avenue; 4950 South Park Avenue; 4215 Howard Road and 4227 Howard Road and the contiguous water tank property to be rezoned from C-2 to NC. -

Our Town Theatre Celebrating Community Through the Arts

8 m o u n t a i n d i s c o v e r i e s Our Town Theatre Celebrating Community Through the Arts Written by: Mary Reisinger Photography by: Lance C. Bell unless otherwise noted Our Town Theatre 121 E. Center Street, Oakland, MD 21550 Inset: Our Town Theatre founder, Jane Avery After its earlier uses as a church hall, an armory, and a to conduct research on community theaters around the museum, an unassuming red brick building on Center country, she did it in her own fashion, taking an extensive Street in Oakland, Maryland, now houses Our Town road trip with her friend Maxie the Wonder Dog. Theatre, a community theater that presents popular play Jane had already collaborated with other arts organizations readings and fully staged plays, musical performances, and in Garrett County. Through her experience with other open mic nights (without microphones because of the local theaters around the United States, she developed an excellent acoustic quality of the hall) throughout the year. appreciation for the significant role that performing arts This group resulted from the vision of the late Jane Avery groups play in the community. In addition to providing (1947-2016), who summered in Garrett County as a child entertainment, Our Town Theatre addresses through per- and who moved here as a young adult, teaching children formance such issues as domestic violence, bullying, and of all ages, but known mostly for her English and theater the sense of being alone that can arise when people confront classes at Southern High School. -

Our Town by Thornton Wilder

The Guide A Theatergoer’s Resource Our Town By Thornton Wilder Education & Community Programs Staff Kelsey Tyler Education & Community Programs Director Clara Hillier Education Programs Coordinator RJ Hodde Community Programs Coordinator Matthew B. Zrebski Resident Teaching Artist Resource Guide Contributors Benjamin Fainstein Literary Manager Mary Blair Production Dramaturg & Literary Associate Nicholas Kessler Stage Door Teaching Artist Table of Contents Mikey Mann Synopsis . 2 Graphic Designer By the Numbers. 2 PCS’s 2015–16 Education & Community Programs are Overview . 2 generously supported by: Characters . 3 Profoundly Populist: Our Town History . 5 Questions . 5 Biography of the Playwright. 7 In His Own Words . 7 Contemporaries: Stella Adler On Thornton Wilder . 8 Writing Exercises . 9 PCS’s education programs are supported in part by a grant from the Performance Exercises . 9 Oregon Arts Commission and the National Endowment for the Arts. Stage Door Program . 10-12 with additional support from Craig & Y. Lynne Johnston Holzman Foundation Mentor Graphics Foundation Juan Young Trust Autzen Foundation and other generous donors. 1 “The life of a village against the life of the stars.” - Thornton Wilder describing Our Town Synopsis A meditation on small-town life, Our Town celebrates the marvel of everyday existence through the fictional citizens of one New England community at the beginning of the twentieth century. The play is conducted by it’s narrator, the Stage Manager of a theater in which the story is performed. It is divided into three distinct acts, covering commonplace and milestone moments in the lives of its characters: daily life, love and marriage, death and dying. Setting 42 degrees 40 minutes north latitude and 70 degrees 37 minutes west longitude Time May 7, 1901 (Act I) • July 7, 1904 (Act II) • Summer 1913 (Act III) Context 76 m. -

The Matchmaker Study Guide

The Matchmaker Study Guide The Matchmaker by Thornton Wilder The following sections of this BookRags Literature Study Guide is offprint from Gale's For Students Series: Presenting Analysis, Context, and Criticism on Commonly Studied Works: Introduction, Author Biography, Plot Summary, Characters, Themes, Style, Historical Context, Critical Overview, Criticism and Critical Essays, Media Adaptations, Topics for Further Study, Compare & Contrast, What Do I Read Next?, For Further Study, and Sources. (c)1998-2002; (c)2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Encyclopedia of Popular Fiction: "Social Concerns", "Thematic Overview", "Techniques", "Literary Precedents", "Key Questions", "Related Titles", "Adaptations", "Related Web Sites". (c)1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Guide to Literature for Young Adults: "About the Author", "Overview", "Setting", "Literary Qualities", "Social Sensitivity", "Topics for Discussion", "Ideas for Reports and Papers". (c)1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. All other sections in this Literature Study Guide are owned and copyrighted by BookRags, Inc. Contents The Matchmaker Study Guide ..................................................................................................... 1 Contents ..................................................................................................................................... -

Thomas Hampson, Baritone

Monday, May 3, 2021 | 3 PM Livestreamed from Gordon K. and Harriet Greenfield Hall and William R. and Irene D. Miller Recital Hall MASTER CLASS & LIVE WEBCAST Distinguished Visiting Artist for Vocal Studies and Distance Learning Thomas Hampson, baritone PROGRAM WOLFGANG AMADEUS “Dove sono i bei momenti” from Le nozze di Figaro, K. 492 MOZART (1756–1791) RICHARD STRAUSS “Wasserrose” from Mädchenblumen, Op. 22 (1864–1949) Jasmine Ismail, soprano Winston Salem, North Carolina Student of Ruth Golden Travis Bloom, piano NED ROREM Emily’s Goodbye Aria from Our Town (b. 1923) HARRY THACKER “Worth While” from Five Songs of Laurence Hope BURLEIGH (1866–1949) RICHARD STRAUSS “Cäcilie,” Op. 27, no. 2 Evangeline Ng, soprano Singapore Student of Joan Patenaude-Yarnell Fumiyasu Kawase, piano GEORGE FRIDERIC “È gelosia” from Alcina, HWV 34 HANDEL (1685–1759) GUSTAV MAHLER “Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht” from Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (1860–1911) Yile Huang, mezzo-soprano Inner Mongolia, China Student of Maitland Peters Tongyao Li, piano FRANZ SCHUBERT “Erlkönig,” Op. 1, D. 328 (1797–1828) WOLFGANG AMADEUS “Tutto è disposto… Aprite un po’quegli ochi” from Le nozze di Figaro, K. 492 MOZART Michael Leyte-Vidal, bass-baritone Palmetto Bay, Florida Student of Ashley Putnam Travis Bloom, piano Alternates WOLFGANG AMADEUS “Ah, chi mi dice mai” from Don Giovanni, K. 527 MOZART HENRI DUPARC “Au pays où se fait la guerre” (1848–1933) Sarah Rachel Bacani, soprano Toms River, New Jersey Student of Cynthia Hoffmann Travis Bloom, piano TEXT AND TRANSLATIONS “Dove sono i bei momenti” from Le nozze di Figaro E Susanna non vien! Sono ansiosa di saper Susanna does not come! come il Conte accolse la proposta. -

Hello, Dolly! from Wilder to Kelly Julie Vatain-Corfdir, Emilie Rault

Harmony at Harmonia? Glamor and Farce in Hello, Dolly! from Wilder to Kelly Julie Vatain-Corfdir, Emilie Rault To cite this version: Julie Vatain-Corfdir, Emilie Rault. Harmony at Harmonia? Glamor and Farce in Hello, Dolly! from Wilder to Kelly. Sorbonne Université Presses. American Musicals: Stage and Screen / La Scène et l’écran, 2019. hal-02443099 HAL Id: hal-02443099 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-02443099 Submitted on 16 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Harmony at Harmonia? Glamor and farce in Hello, Dolly!, from Wilder to Kelly Julie Vatain-Corfdir & Émilie Rault When Hello, Dolly! opened on Broadway in January 1964, immediately to be hailed as “a musical shot through with enchantment,”1 New York audiences were by no means greeting Dolly for the first time. Through a process of recycling which probably owed as much to the potential of the original story as it did to a logic of commercial security, the story of Mrs. Dolly Levi – the meddling matchmaker who sorts out everyone’s love lives and contrives to marry her biggest client herself – had been prosperous on stage and screen for the previous ten years, and would continue to attract audiences to this day.2 Not unlike My Fair Lady, which previously held the record for longest-running Broadway musical, Hello, Dolly! trod on the “surer road to success,”3 with a book based on a popular play by an acclaimed playwright – Thornton Wilder’s The Matchmaker –, and one which had already been famously adapted to the screen with a cast starring, among others, Shirley Booth and Shirley MacLane.