Hello, Dolly! from Wilder to Kelly Julie Vatain-Corfdir, Emilie Rault

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directing and Assisting Credits American Theatre

917-854-2086 American and Canadian citizen Member of SSDC www.joelfroomkin.com [email protected] Directing and Assisting Credits American Theatre Artistic Director The New Huntington Theatre, Huntington Indiana. The Supper Club (upscale cabaret venue housing musical revues) Director/Creator Productions include: Welcome to the Sixties, Hooray For Hollywood, That’s Amore, Sounds of the Seventies, Hoosier Sons, Puttin’ On the Ritz, Jekyll and Hyde, Treasure Island, Good Golly Miss Dolly, A Christmas Carol, Singing’ The King, Fly Me to the Moon, One Hit Wonders, I’m a Believer, Totally Awesome Eighties, Blowing in the Wind and six annual Holiday revues. Director (Page on Stage one-man ‘radio drama’ series): Sleepy Hollow, Treasure Island, A Christmas Carol, Jekyll and Hyde, Dracula, Sherlock Holmes, Different Stages (320 seat MainStage) The Sound of Music (Director/Scenic & Projection Design) Moonlight and Magnolias (Director/Scenic Design) Les Misérables (Director/Co-Scenic and Projection Design) Productions Lord of the Flies (Director) Manchester University The Laramie Project (Director) Manchester University The Foreigner (Director) Manchester University Infliction of Cruelty (Director/Dramaturg) Fringe NYC, 2006 *Winner of Fringe 2006 Outstanding Excellence in Direction Award Thumbs, by Rupert Holmes (Director) Cape Playhouse, MA *Cast including Kathie Lee Gifford, Diana Canova (Broadway’s Company, They’re Playing our Song), Sean McCourt (Bat Boy), and Brad Bellamy The Fastest Woman Alive (Director) Theatre Row, NY *NY premiere of recently published play by Outer Critics Circle nominee, Karen Sunde *published Broadway Musicals of 1928 (Director) Town Hall, NYC *Cast including Tony-winner Bob Martin, Nancy Anderson, Max Von Essen, Lari White. -

Senior Musical Theater Recital Assisted by Ms

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Joy Kenyon Senior Musical Theater Recital assisted by Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist Belhaven University Percussion Ensemble Women’s Chorus, Scott Foreman, Daniel Bravo James Kenyon, & Jessica Ziegelbauer Monday, April 13, 2015 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performers. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert Please turn off all cell phones and electronics. PROGRAM Just Leave Everything To Me from Hello Dolly Jerry Herman • b. 1931 100 Easy Ways To Lose a Man from Wonderful Town Leonard Bernstein • 1918 - 1990 Betty Comden • 1917 - 2006 Adolph Green • 1914 - 2002 Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist The Man I Love from Lady, Be Good! George Gershwin • 1898 - 1937 Ira Gershwin • 1896 - 1983 Love is Here To Stay from The Goldwyn Follies Embraceable You from Girl Crazy Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Ms. Maggie McLinden, Accompanist; Scott Foreman, Bass Guitar; Daniel Bravo, Percussion Steam Heat (Music from The Pajama Game) Choreography by Mrs. Kellis McSparrin Oldenburg Dancer: Joy Kenyon He Lives in You (reprise) from The Lion King Mark Mancina • b. 1957 Jay Rifkin & Lebo M. • b. 1964 arr. Dr. Owen Rockwell Joy Kenyon, Soprano; Belhaven University Percussion Ensemble; Maddi Jolley, Brooke Kressin, Grace Anna Randall, Mariah Taylor, Elizabeth Walczak, Rachel Walczak, Evangeline Wilds, Julie Wolfe & Jessica Ziegelbauer INTERMISSION The Glamorous Life from A Little Night Music Stephen Sondheim • b. 1930 Sweet Liberty from Jane Eyre Paul Gordon • b. -

Main Completed Newsletter

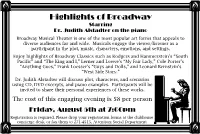

Unique on Long Island, the Long Island Mandolin And Guitar Orchestra (LIMAGO) began in the 1950’s as an adult education class sponsored by a School District in Nassau County. It has since evolved into a not-for-profit organization with its aims being to preserve the music of the mandolin, to increase its awareness of the history and potential of the mandolin, and to provide an educational, as well as enjoyable, listening experience. The Orchestra is comprised of mandolins, mandolas, mandocellos, a mandobass, guitars, an accordion, and vocalists. Although the members span various age groups and come from all walks of life, they are bound together by a desire to increase the popularity of the mandolin, and by a love of music. You won’t want to miss this enjoyable music performance! Registration is required. Please drop your registration forms at the clubhouse concierge desk, or fax them to 271-4515, Attention: Social Department Highlights of Broadway Starring Dr. Judith Alstadter on the piano Broadway Musical Theater is one of the most popular art forms that appeals to diverse audiences far and wide. Musicals engage the viewer/listener as a participant in the plot, music, characters, emotions, and settings. Enjoy highlights of Broadway Classics such as Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “South Pacific” and “The King and I,” Lerner and Loewe’s “My Fair Lady,” Cole Porter’s “Anything Goes,” Frank Loesser’s “Guys and Dolls,” and Leonard Bernstein’s “West Side Story.” Dr. Judith Alstadter will discuss plot, characters, and scenarios using CD, DVD excerpts, and piano examples. Participants will be invited to share their personal experiences of these works. -

PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016

For Immediate Release January 2016 PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016 Playhouse Square is proud to announce that the U.S. National Tour of ANNIE, now in its second smash year, will play January 12 - 17 at the Connor Palace in Cleveland. Directed by original lyricist and director Martin Charnin for the 19th time, this production of ANNIE is a brand new physical incarnation of the iconic Tony Award®-winning original. ANNIE has a book by Thomas Meehan, music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Martin Charnin. All three authors received 1977 Tony Awards® for their work. Choreography is by Liza Gennaro, who has incorporated selections from her father Peter Gennaro’s 1977 Tony Award®-winning choreography. The celebrated design team includes scenic design by Tony Award® winner Beowulf Boritt (Act One, The Scottsboro Boys, Rock of Ages), costume design by Costume Designer’s Guild Award winner Suzy Benzinger (Blue Jasmine, Movin’ Out, Miss Saigon), lighting design by Tony Award® winner Ken Billington (Chicago, Annie, White Christmas) and sound design by Tony Award® nominee Peter Hylenski (Rocky, Bullets Over Broadway, Motown). The lovable mutt “Sandy” is once again trained by Tony Award® Honoree William Berloni (Annie, A Christmas Story, Legally Blonde). Musical supervision and additional orchestrations are by Keith Levenson (Annie, She Loves Me, Dreamgirls). Casting is by Joy Dewing CSA, Joy Dewing Casting (Soul Doctor, Wonderland). The tour is produced by TROIKA Entertainment, LLC. The production features a 25 member company: in the title role of Annie is Heidi Gray, an 11- year-old actress from the Augusta, GA area, making her tour debut. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Stanley Chase Papers LSC.1090

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6h4nc876 No online items Finding Aid for the Stanley Chase Papers LSC.1090 Processed by Timothy Holland and Joshua Amberg in the Center For Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Laurel McPhee, Fall 2005; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé and edited by Josh Fiala, Caroline Cubé, Laurel McPhee and Amy Shung-Gee Wong. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 December 11. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Stanley Chase LSC.1090 1 Papers LSC.1090 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Stanley Chase papers Creator: Chase, Stanley Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1090 Physical Description: 157.2 Linear Feet(105 boxes, 12 oversize boxes, 27 map folders) Date (inclusive): circa 1925-2001 Date (bulk): 1955-1989 Abstract: Stanley Chase (1928-) was a theater, film, and television producer. The collection consists of production and business files, original production drawings, posters, press clippings, sound recordings, and scripts from his major projects. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements CONTAINS AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS: This collection contains both processed and unprocessed audiovisual materials. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Our-Town-Study-Guide.Pdf

STUDY GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PERFORMANCE INFORMATION PAGE 3 TORNTON WILDER PAGE 4 THORNTON WILDER CHRONOLOGY PAGE 5 OUR TOWN: A BRIEF HISTORY PAGE 6 PLAY SYNOPSIS PAGE 7 CAST OF CHARACTERS PAGE 10 THE PULITZER PRIZE PAGE 11 OUR TOWN: A HISTORICAL TIMELINE PAGE 12 THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGING PAGE 16 THEMES OF OUR TOWN PAGE 17 NEW HAMPSHIRE PAGE 18 SCENIC DESIGN PAGE 19 PROMPTS FOR DISCUSSION PAGE 21 AUDIENCE ETIQUETTE PAGE 22 STUDENT EVALUATION PAGE 23 TEACHER EVALUATION PAGE 24 New Stage Theatre Presents OUR TOWN by Thornton Wilder Directed by Francine Thomas Reynolds Sponsored by Sanderson Farms Stage Manager Lighting Designer Scenic Designer Elise McDonald Brent Lefavor Dex Edwards Costume Designer Technical Director/Properties Lesley Raybon Richard Lawrence There will be one 10-minute intermission THE CAST Cast (in order of appearance) STAGE MANAGER Sharon Miles DR. GIBBS Larry Wells HOWIE NEWSOME Christan McLaurine JOE CROWELL, JR. Ben Sanders MRS. GIBBS Malaika Quarterman MRS. WEBB Kerri Sanders GEORGE GIBBS Cliff Miller * REBECCA GIBBS Mary Frances Dean WALLY WEBB Jeffrey Cornelius EMILY WEBB Devon Caraway* PROFESSOR WILLARD Amanda Dear MR. WEBB Yohance Myles* WOMAN #1 LaSharron Purvis SIMON STIMSON Jeff Raab WOMAN #2 Hope Prybylski WOMAN #3 Ashanti Alexander CONSTABLE WARREN Chris Roebuck MRS. SOAMES Joy Amerson SI CROWELL Alex Forbes SAM CRAIG Jake Bell JOE STODDARD James Anderson FARMER MCCARTY Peter James VIOLINIST Miranda Kunk *The actor appears through the courtesy of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Profes- sional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. THORNTON WILDER Thornton Wilder was born in Madison, Wisconsin on April 17, 1897. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

Now That She's Gone

The Carl Cherry Center for the Arts presents... Layne Littlepage in BROADWAY LEADING LADIES: Viva the Divas! With Rick Yramtegui at the piano July 27th – August 19th, 2012 Fridays and Saturdays at 7:30 pm, Sundays at 3 pm Layne Littlepage returns to the Carl Cherry Center with a new and delightful show about the leg- endary female stars of Broadway’s greatest musicals: Julie Andrews, Ethel Merman, Mary Mar- tin, Barbra Streisand, Fanny Brice, Beatrice Lillie, Carol Channing, Elaine Stritch and more! Un- forgettable songs and stories. What makes a legend a legend? And what happens when legends collide, or fight for the same role? Find out! Tickets: $25 Information and Reservations: (831)238-0092, or ticketguys.com Now That She’s Gone Written & Performed by Ellen Snortland Friday, August 24th at 7:30 pm Saturday, August 25th at 7:30 pm Sunday, August 26th at 2:00 pm & 7:30 pm “Now That She’s Gone” is a play that explores Ellen Snortland’s often hilarious, irreverent and sometimes torturous relationship with her Norwegian-American mother. “Now That She’s Gone” has been described as a Lily Tomlin / Garrison Keillor hybrid… passionate, poignant and funny in turns. A memoir piece with Eleanor Roosevelt, sex, drugs and lutefisk, the play and performance has received rave reviews and standing ovations in California, Minnesota, New York, and Washington, D.C., as well as France, Holland, Scotland… and Norway. Tickets are $20, and will be available at the door (if space is available), or can be purchased online at carlcherrycenter.org For more info, email [email protected] or call 626-798-8421, or visit Ellen’s website at http://www.snortland.com “An Evening with William Blake” with Norma and Richard Mayer, and Bill Minor Friday, August 31st, at 7:30pm Soprano Norma Mayer and flutist Richard Mayer will perform poems of William Blake set to music by Ralph Vaughan Williams and other composers. -

Our Town by Thornton Wilder

The Guide A Theatergoer’s Resource Our Town By Thornton Wilder Education & Community Programs Staff Kelsey Tyler Education & Community Programs Director Clara Hillier Education Programs Coordinator RJ Hodde Community Programs Coordinator Matthew B. Zrebski Resident Teaching Artist Resource Guide Contributors Benjamin Fainstein Literary Manager Mary Blair Production Dramaturg & Literary Associate Nicholas Kessler Stage Door Teaching Artist Table of Contents Mikey Mann Synopsis . 2 Graphic Designer By the Numbers. 2 PCS’s 2015–16 Education & Community Programs are Overview . 2 generously supported by: Characters . 3 Profoundly Populist: Our Town History . 5 Questions . 5 Biography of the Playwright. 7 In His Own Words . 7 Contemporaries: Stella Adler On Thornton Wilder . 8 Writing Exercises . 9 PCS’s education programs are supported in part by a grant from the Performance Exercises . 9 Oregon Arts Commission and the National Endowment for the Arts. Stage Door Program . 10-12 with additional support from Craig & Y. Lynne Johnston Holzman Foundation Mentor Graphics Foundation Juan Young Trust Autzen Foundation and other generous donors. 1 “The life of a village against the life of the stars.” - Thornton Wilder describing Our Town Synopsis A meditation on small-town life, Our Town celebrates the marvel of everyday existence through the fictional citizens of one New England community at the beginning of the twentieth century. The play is conducted by it’s narrator, the Stage Manager of a theater in which the story is performed. It is divided into three distinct acts, covering commonplace and milestone moments in the lives of its characters: daily life, love and marriage, death and dying. Setting 42 degrees 40 minutes north latitude and 70 degrees 37 minutes west longitude Time May 7, 1901 (Act I) • July 7, 1904 (Act II) • Summer 1913 (Act III) Context 76 m. -

U.S. National Tour of the West End Smash Hit Musical To

Tweet it! You will always love this musical! @TheBodyguardUS comes to @KimmelCenter 2/21–26, based on the Oscar-nominated film & starring @Deborah_Cox Press Contacts: Amanda Conte [email protected] (215) 790-5847 Carole Morganti, CJM Public Relations [email protected] (609) 953-0570 U.S. NATIONAL TOUR OF THE WEST END SMASH HIT MUSICAL TO PLAY PHILADELPHIA’S ACADEMY OF MUSIC FEBRUARY 21–26, 2017 STARRING GRAMMY® AWARD NOMINEE AND R&B SUPERSTAR DEBORAH COX FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, December 22, 2016) –– The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts and The Shubert Organization proudly announce the Broadway Philadelphia run of the hit musical The Bodyguard as part of the show’s first U.S. National tour. The Bodyguard will play the Kimmel Center’s Academy of Music from February 21–26, 2017 starring Grammy® Award-nominated and multi-platinum R&B/pop recording artist and film/TV actress Deborah Cox as Rachel Marron. In the role of bodyguard Frank Farmer is television star Judson Mills. “We are thrilled to welcome this new production to Philadelphia, especially for fans of the iconic film and soundtrack,” said Anne Ewers, President & CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “This award-winning stage adaption and the incomparable Deborah Cox will truly bring this beloved story to life on the Academy of Music stage.” Based on Lawrence Kasdan’s 1992 Oscar-nominated Warner Bros. film, and adapted by Academy Award- winner (Birdman) Alexander Dinelaris, The Bodyguard had its world premiere on December 5, 2012 at London’s Adelphi Theatre. The Bodyguard was nominated for four Laurence Olivier Awards including Best New Musical and Best Set Design and won Best New Musical at the WhatsOnStage Awards.