Racing Appeals Tribunal Nsw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expression of Recombinant Human Androgen Receptor and Its Use for Screening Methods

Institut für Physiologie FML Weihenstephan Technische Universität München Expression of recombinant human androgen receptor and its use for screening methods Ellinor Rose Sigrid Bauer Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr. B. Hock Prüfer der Dissertation: Univ.-Prof. Dr. H. H. D. Meyer Univ.-Prof. Dr. H. Sauerwein (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn) Die Dissertation wurde am 31.10.2002 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt am 03.12.2002 angenommen. Introduction Content 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. ENDOCRINE DISRUPTERS 5 1.2. ANDROGENS AND ANTIANDROGENS 7 1.2.1. DEFINITIONS 7 1.2.2. MODE OF ACTION 8 1.3. STRUCTURES OF ENDOCRINE DISRUPTERS 10 1.4. STRATEGIES FOR MONITORING ANDROGEN ACTIVE SUBSTANCES 13 1.4.1. IN VIVO METHODS 13 1.4.2. IN VITRO METHODS 15 1.5. OBJEKTIVE OF THE STUDIES 18 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS ................................................................................................................. 19 2.1. PREPARATION OF RECEPTORS 19 2.2. ASSAY SYSTEMS 19 2.2.1. IN SOLUTION AR ASSAY 19 2.2.2. IMMUNO-IMMOBILISED RECEPTOR ASSAY (IRA) 20 2.2.3. PR AND SHBG ASSAYS 21 2.2.4. DATA EVALUATION 21 2.3. ANALYTES 22 3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ................................................................................................................. 23 3.1. DEVELOPMENT OF NEW ASSAY SYSTEMS 23 3.1.1. BAR ASSAY 23 3.1.2. CLONING OF THE HUMAN AR AND PRODUCTION OF FUNCTIONAL PROTEIN 24 3.1.3. DEVELOPMENT OF A SCREENING ASSAY ON MICROTITRE PLATES (IRA) 25 3.2. -

(Cyp19a1b-GFP) Zebrafish Embryos

Screening Estrogenic Activities of Chemicals or Mixtures In Vivo Using Transgenic (cyp19a1b-GFP) Zebrafish Embryos Franc¸ois Brion1, Yann Le Page2, Benjamin Piccini1, Olivier Cardoso1, Sok-Keng Tong3, Bon-chu Chung3, Olivier Kah2* 1 Unite´ d’Ecotoxicologie in vitro et in vivo, Direction des Risques Chroniques, Institut National de l’Environnement Industriel et des Risques (INERIS), Verneuil-en- Halatte, France, 2 Universite´ de Rennes 1, Institut de Recherche Sante´ Environnement & Travail (IRSET), INSERM U1085, BIOSIT, Campus de Beaulieu, Rennes France, 3 Taiwan Institute of Molecular Biology, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan Abstract The tg(cyp19a1b-GFP) transgenic zebrafish expresses GFP (green fluorescent protein) under the control of the cyp19a1b gene, encoding brain aromatase. This gene has two major characteristics: (i) it is only expressed in radial glial progenitors in the brain of fish and (ii) it is exquisitely sensitive to estrogens. Based on these properties, we demonstrate that natural or synthetic hormones (alone or in binary mixture), including androgens or progestagens, and industrial chemicals induce a concentration-dependent GFP expression in radial glial progenitors. As GFP expression can be quantified by in vivo imaging, this model presents a very powerful tool to screen and characterize compounds potentially acting as estrogen mimics either directly or after metabolization by the zebrafish embryo. This study also shows that radial glial cells that act as stem cells are direct targets for a large panel of endocrine disruptors, calling for more attention regarding the impact of environmental estrogens and/or certain pharmaceuticals on brain development. Altogether these data identify this in vivo bioassay as an interesting alternative to detect estrogen mimics in hazard and risk assessment perspective. -

伊域化學藥業(香港)有限公司 Cyclopentyl Substituted Compounds

® 伊 域 化 學(香 藥 香 港) 業 港有 有 限 限 公 公 司 司 YICK-VIC CHEMICALS & PHARMACEUTICALS (HK) LTD Rm 1006, 10/F, Hewlett Centre, Tel: (852) 25412772 (4 lines) No. 52-54, Hoi Yuen Road, Fax: (852) 25423444 / 25420530 / 21912858 Kwun Tong, E-mail: [email protected] YICKYICK----VICVICVICVIC 伊域伊域伊域 Kowloon, Hong Kong. Site: http://www.yickvic.com Cyclopentyl Substituted Compounds Product Code CAS Product Name CC-0052BA 39746-00-4 (-)-COREY LACTONE BENZOATE CC-3702AD 1211-29-6 (-)-METHYL JASMONATE SPI-4467C 87269-86-1 (-)-OCTAHYDROCYCLOPENTA[B]PYRROLE-2-CARBOXYLIC ACID HYDROCHLORIDE SPI-4467A 93779-30-7 (+/-)-OCTAHYDROCYCLOPENTA[B]PYRROLE-2-CARBOXYLIC ACID HYDROCHLORIDE SPI-2956FG 142217-81-0 (1S,3R,4S)-2-AMINO-9-(4-BENZYLOXY)-3-(BENZYLOXYMETHYL)-2-METHYLIDENECYCLOPENTYL-3H-PURINE-9-ONE SPI-2956FJ 142217-78-5 (2R,3S,5S)-3-(BENZYLOXY)-5-[2-[[(4-METHOXYPHENYL)DIPHENYLMETHYL]AMINO]-6-(PHENYLMETHOXY)-9H-PURIN-9-Y L]-2-(BENZYLOXYMETHYL)CYCLOPENTANOL SPI-1560DH 4167-77-5 1,1-CYCLOPENTANEDICARBOXYLIC ACID DIETHYL ESTER SPI-2808C 5763-44-0 1,2-CYCLOPENTANE DICARBOXIMIDE CC-1957B 1222-05-5 1,3,4,6,7,8-HEXAHYDRO-4,6,6,7,8,8-HEXAMETHYLCYCLOPENTA[G]-2-BENZOPYRAN SPI-1246B 3859-41-4 1,3-CYCLOPENTANEDIONE SPI-1955AA 646-06-0 1,3-DIOXOLANE SPI-3082AA 54078-29-4 1,8-DIAZAFLUOREN-9-ONE UNIE-13864 564-35-2 11-KETOTESTOSTERONE SPI-0098CA 640-87-9 17-ALPHA,21-DIHYDROXYPREGN-4-ENE-3,20-DIONE 21-ACETATE UNIE-13126 302-76-1 17ALPHA-METHYL-17BETA-ESTRADIOL UNIE-14695 3563-27-7 17BETA-DIHYDROQUILIN UNIE-2836 10316-79-7 1-AMINO-1-CYCLOPENTANEMETHANOL SPI-3077CB 61379-64-4 1-AMINO-4-CYCLOPENTYLPIPERAZINE -

TGA Review of Hgps

A REVIEW TO UPDATE AUSTRALIA’S POSITION ON THE HUMAN SAFETY OF RESIDUES OF HORMONE GROWTH PROMOTANTS (HGPs) USED IN CATTLE Prepared by Chemical Review and International Harmonisation Section Office of Chemical Safety Therapeutic Goods Administration of the Department of Health and Ageing Canberra July 2003 A draft of this report was tabled at the 25th Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Pesticides and Health (ACPH), held in Canberra on the 1st May 2003. The report was subsequently endorsed out-of-session by the ACPH. Hormone Growth Promotants TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................................................4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................................7 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................................................9 HEALTH CONCERNS ASSOCIATED WITH HGP S................................................................................................................9 DIFFICULTIES ASSOCIAT ED WITH ASSESSING THE SAFETY OF HGPS.........................................................................10 RISK ASSESSMENTS OF HGP S .........................................................................................................................................10 PURPOSE OF THE CURRENT -

Biodegradation of the Steroid Progesterone in Surface Waters

Biodegradation of the Steroid Progesterone in Surface Waters A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Jasper Oreva Ojoghoro Institute of the Environment, Health and Societies May, 2017 Abstract Many studies measuring the occurrence of pharmaceuticals, understanding their environmental fate and the risk they pose to surface water resources have been published. However, very little is known about the relevant transformation products which result from the wide range of biotic and abiotic degradation processes that these compounds undergo in sewers, storage tanks, during engineered treatment and in the environment. Thus, the present study primarily investigated the degradation of the steroid progesterone (P4) in natural systems (rivers), with a focus on the identification and characterisation of transformation products. Initial work focussed on assessing the removal of selected compounds (Diclofenac, Fluoxetine, Propranolol and P4) from reed beds, with identification of transformation products in a field site being attempted. However, it was determined that concentrations of parent compounds and products would be too low to work with in the field, and a laboratory study was designed which focussed on P4. Focus on P4 was based on literature evidence of its rapid biodegradability relative to the other model compounds and its usage patterns globally. River water sampling for the laboratory-based degradation study was carried out at 1 km downstream of four south east England sewage works (Blackbirds, Chesham, High Wycombe and Maple Lodge) effluent discharge points. Suspected P4 transformation products were initially identified from predictions by the EAWAG Biocatalysis Biodegradation Database (EAWAG BBD) and from a literature review. At a later stage of the present work, a replacement model for EAWAG BBD (enviPath) which became available, was used to predict P4 degradation and results were compared. -

Randlabspring 2018 Newsletter Spring 2018 Newsletter

RANDLABSPRING 2018 NEWSLETTER SPRING 2018 NEWSLETTER ALTRENOGEST has been used in performance fillies and mares for over 20 years. So why is its use now being restricted? In no mood to work. Mares behaving badly. Randlab’s Global Technical Veterinarian, Dr Michael Robinson, presents the facts behind the current Altrenogest debate KEY POINTS Altrenogest is still able to be used in performance mares that are: · Racing in NSW (oral only and not within one clear day of racing). · Not competing in official Equestrian Australia/FEI events · Non-competition fillies and mares · Pleasure/recreational fillies and mares · Breeding mares Under the Australian Rules of Racing and FEI Clean Sport For Horses Regulations, it is illegal to use Altrenogest in male horses. Altrenogest injection delivers a peak concentration that is approximately seven times that achieved by daily oral administration of Altrenogest. All current formulations of Altrenogest contain a low level of background impurities including trenbolone and trendione. The higher peaks obtained with Altrenogest injection may also result in higher peaks of any impurities and may lead to a positive swab. Altrenogest injections maintain plasma levels above those of daily oral Altrenogest for a period of 5-7 days following injection. This may be compounded by repeated weekly injections which results in plasma levels that are sustained for longer. Nothing has changed with the oral formulations of Altrenogest as there was one clear day between administration and racing (ie Thursday for over 20 years. However, its use has recently been brought administration for a Saturday race). into question by racing authorities. So why the change? Racing NSW continues to allow the use of oral Altrenogest up until one clear As most veterinarians are now aware, Racing Victoria issued a notice on 19 day from racing. -

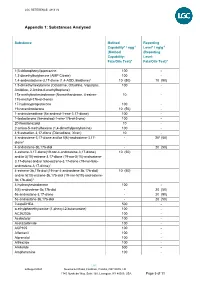

Appendix 1: Substances Analysed

LGC REFERENCE: 4813 V2 Appendix 1: Substances Analysed Substance Method Reporting Capability* / ngg-1 Level* / ng/g-1 (Method (Reporting Capability: Level: Fats/Oils Test)4 Fats/Oils Test)4 1(3-chlorophenyl)piperazine 100 - 1,3-dimethylbutylamine (AMP Citrate) 100 - 1,4-androstadiene-3,17-dione (1,4-ADD, Boldione)2 10 (50) 10 (50) 1,5-dimethylhexylamine (Octodrine, Ottodrina, Vaporpac, 100 - Amidrine, 2-Amino-6-methylheptane) 17a-methylnortestosterone (Normethandrone, 4-estren- 10 - 17a-methyl-17b-ol-3-one) 17-hydroxyprogesterone 100 - 19-norandrosterone 10 (50) - 1-androstenedione (5a-androst-1-ene-3,17-dione) 100 - 1-testosterone (5a-androst-1-ene-17b-ol-3-one) 100 - 20-Norstanozolol 10 - 2-amino-5-methylhexane (1,4-dimethylpentylamine) 100 - 4,9-estradien-3,17-dione (Dienedione, Xtren) 10 - 4-androstene-3,17-dione and/or 5(6)-androstene-3,17- - 203 (50) dione1 4-androstene-3b,17b-diol - 20 (50) 4-estrene-3,17-dione(19-nor-4-androstene-3,17-dione) 10 (50) and/or 5(10)-estrene-3,17-dione (19-nor-5(10)-androstene- 3,17-dione) and/or 5(6)-estrene-3,17-dione (19-nor-5(6)- androstene-3,17-dione)1 4-estrene-3b,17b-diol (19-nor-4-androstene-3b,17b-diol) 10 (50) and/or 5(10)-estrene-3b,17b-diol (19-nor-5(10)-androstene- 3b,17b-diol)1 4-hydroxytestosterone 100 - 5(6)-androstene-3b,17b-diol - 20 (50) 5a-androstane-3,17-dione - 20 (50) 5a-androstane-3b,17b-diol - 20 (50) 7-ketoDHEA 500 - α-ethylphenethylamine (1-phenyl-2-butanamine) 100 - AC262536 100 - Acebutolol 100 - Acetazolamide 100 - ACP105 100 - Alfentanil 100 - Alprenolol 100 - Althiazide -

Screening Estrogenic Activities of Chemicals Or Mixtures in Vivo Using Transgenic (Cyp19a1b-GFP) Zebrafish Embryos

Screening Estrogenic Activities of Chemicals or Mixtures In Vivo Using Transgenic (cyp19a1b-GFP) Zebrafish Embryos François Brion, Yann Le Page, Benjamin Piccini, Olivier Cardoso, Sok-Keng Tong, Bon-Chu Chung, Olivier Kah To cite this version: François Brion, Yann Le Page, Benjamin Piccini, Olivier Cardoso, Sok-Keng Tong, et al.. Screening Es- trogenic Activities of Chemicals or Mixtures In Vivo Using Transgenic (cyp19a1b-GFP) Zebrafish Em- bryos. PLoS ONE, Public Library of Science, 2012, 7 (5), pp.e36069. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036069. hal-00877371 HAL Id: hal-00877371 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00877371 Submitted on 28 Oct 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Screening Estrogenic Activities of Chemicals or Mixtures In Vivo Using Transgenic (cyp19a1b-GFP) Zebrafish Embryos Franc¸ois Brion1, Yann Le Page2, Benjamin Piccini1, Olivier Cardoso1, Sok-Keng Tong3, Bon-chu Chung3, Olivier Kah2* 1 Unite´ d’Ecotoxicologie in vitro et in vivo, Direction des Risques Chroniques, Institut National de l’Environnement Industriel et des Risques (INERIS), Verneuil-en- Halatte, France, 2 Universite´ de Rennes 1, Institut de Recherche Sante´ Environnement & Travail (IRSET), INSERM U1085, BIOSIT, Campus de Beaulieu, Rennes France, 3 Taiwan Institute of Molecular Biology, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan Abstract The tg(cyp19a1b-GFP) transgenic zebrafish expresses GFP (green fluorescent protein) under the control of the cyp19a1b gene, encoding brain aromatase. -

Impairment of Zebrafish Reproduction Upon Exposure to Melengestrol

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/146506; this version posted June 6, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Impairment of zebrafish reproduction upon exposure to melengestrol acetate Kewen Xiong, Chunyun Zhong, Xin Wang Department of Environmental Toxicity, Third Hospital of Shanxi University Keywords: Melengestrol acetate; reproduction; Endocrine disruption; progestin Abstract Synthetic progestins contamination is common in the aquatic ecosystem, which may lead to serious health problem on aquatic animals. Melengestrol acetate (MGA) has been detected in the aquatic environment; however, its potential effects on fish reproduction are largely unclear. Here, we aimed to investigate the endocrine disruption and impact of MGA on zebrafish reproduction. Six-month old reproductive zebrafish were exposed to four nominal concentrations of MGA (1, 10, 100 and 200 ng/L) for 15 days. Treatment with MGA reduced the egg production with a significant decrease at 200 ng/L. The circulating concentrations of estradiol and testosterone in female zebrafish or 11-keto testosterone in male zebrafish were significantly diminished compared to the non-exposed control fish. The early embryonic development or hatching rates were unaffected during the MGA exposure. Our results indicated that MGA was a potent endocrine disruptor in fish and the fish reproduction could be impaired even during a short-term exposure to MGA. bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/146506; this version posted June 6, 2017. -

University of Groningen Multi-Residue Analysis of Growth Promotors

University of Groningen Multi-residue analysis of growth promotors in food-producing animals Koole, Anneke IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 1998 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Koole, A. (1998). Multi-residue analysis of growth promotors in food-producing animals. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 01-10-2021 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION This chapter gives an overview of the subjects dealt with in this thesis. -

Season 2018/19

A portion of every bet, betters WA racing. HHARNESSWA WA SEASON 2018/19 SEASON INFO Your season go-to for Showcasing feature race details, the Regions notices and contacts Meet Hayley Wheeler, the face behind the scenes at Collie Harness Racing Club the BRIDGE BAR Michael Radley’s insights on the idea the location the facilities SEASON 2018/19 Our profits stay in WA and fund a better racing industry. THE JOURNEY AHEAD Gamble responsibly. ruok.org.au SEASON 2018/19 FOLLOW RWWA CONTENTS 04 08 12 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 04 New Season | New Hope 03 WELCOME Tim Walker reminisces about the 2017/18 season, highlighting some of its stand-out performers and talks with industry experts to 16 COMMUNITY TAB preview the 2018/19 season ahead. Young riders competing in the Riding for the Disabled Association WA (RDAWA) 2018 Community TAB State Games. 08 The Bridge Bar Gloucester Park has seized the opportunity 18 BOTRA brought by the new Matagarup Bridge and Details of the third running of the Mouse have created The Bridge Bar, the perfect Racing Day Fundraiser, Stallion Service meeting place before Optus Stadium events. Auction and Downunder Sulky raffle. 21 2018/19 FEATURE RACES 12 Showcasing the Regions A detailed list of all feature race dates Julio Santarelli talks to Collie Harness Racing for the 2018/19 harness racing season. Club volunteer Hayley Wheeler, who's behind- the-scenes contributions to the club do not go unnoticed. 1 HWA SEASON 2018-19 HWA INDUSTRY NOTICES HARNESS WA EDITION 1 29 48 Stewards Notices Amendments to Rules EDITOR: Hayley -

University of Nevada, Reno Environmental Fate of Trenbolone

University of Nevada, Reno Environmental Fate of Trenbolone Acetate Used in Animal Agriculture: Mechanistic Studies of Hormone Biodegradation in Various Redox Conditions A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Civil and Environmental Engineering by Jaewoong Lee Dr. Edward P. Kolodziej/Thesis Advisor December, 2011 i Abstract Recent studies have been reported that natural and synthetic hormones are major endocrine-disrupting contaminants (EDCs) that can cause contaminant-associated reproductive and developmental alternation on aquatic organisms. In particular, synthetic steroids such as trenbolone acetate (TBA) are widely used as growth promoters in beef cattle. It has been reported that livestock excrete potential endocrine disrupting hormones such as the TBA metabolites (17 α-trenbolone, 17 β-trenbolone, and trendione) into aquatic environments. Although livestock likely contain much higher levels of steroid contaminants due to the increased use of growth-promoting hormones, relatively little is known about the fate of these synthetic steroids under various aquatic environments. Therefore, this study undertook a series of experiments using biodegradation microcosms to develop a mechanistic understanding of the fate of TBA metabolites in various redox conditions. Redox potentials were controlled by using reagents (titanium(III) citrate, L- cysteine, and dithiothreitol) to develop anaerobic (E h < -400 mV), anoxic (-400 mV < Eh < -200 mV), and suboxic (-200 mV < E h < 0 mV) conditions. In aerobic conditions (E h > 100 mV), although abiotic losses in sterile controls were observed for three androgen steroids, 17 α-trenbolone and 17 β-trenbolone were degraded by as much as 80% and 40% by biotic processes over 10 days.