Public Goods”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asustust Ja Maakasutust Suunavad Keskkonnatingimused

LÄÄNE MAAVALITSUS LÄÄNE MAAKONNAPLANEERINGU TEEMAPLANEERING ASUSTUST JA MAAKASUTUST SUUNAVAD KESKKONNATINGIMUSED HAAPSALU 2005 Teemaplaneering Asustust ja maakasutust suunavad keskkonnatingimused SISUKORD lk 1. EESSÕNA______________________________________________________3 2. ASUSTUST JA MAAKASUTUST SUUNAVAD KESKKONNATINGIMUSED____5 2.1. Väärtuslike maastike säilimise ja kasutamise tingimused__________________5 2.1.1. Väärtuslikud kultuur- ja loodusmaastikud_______________________________5 2.1.2. Väärtuslikud linnamaastikud_________________________________________7 2.2. Rohelise võrgustiku säilimise ja kasutamise tingimused___________________8 3. LÄÄNEMAA VÄÄRTUSLIKUD MAASTIKUD___________________________10 3.1. Neugrundi madalik_________________________________________________10 3.2. Osmussaar________________________________________________________11 3.3. Lepajõe – Nõva – Peraküla – Dirhami_________________________________13 3.4. Vormsi___________________________________________________________15 3.5. Ramsi – Einbi_____________________________________________________16 3.6. Kadarpiku – Saunja – Saare_________________________________________18 3.7. Hobulaid_________________________________________________________19 3.8. Paralepa – Pullapää – Topu__________________________________________20 3.9. Palivere__________________________________________________________22 3.10. Kuijõe – Keedika – Uugla – Taebla – Kirimäe – Võnnu – Ridala_________23 3.11. Ridala__________________________________________________________24 3.12. Koluvere – Kullamaa_____________________________________________26 -

KIILI VALLA ARENGUKAVA 2030 Kinnitatud Kiili Vallavolikogu 11.10.2018 Määrusega Nr 10

KIILI VALLA ARENGUKAVA 2030 Kinnitatud Kiili Vallavolikogu 11.10.2018 määrusega nr 10 Oktoober 2018 1 Sisukord Sisukord ..................................................................................... 2 Sissejuhatus .............................................................................. 4 1 Kiili valla arengueeldused ..................................................... 5 1.1 Asend ja ruumiline muster ........................................................... 5 1.2 Rahvastik ..................................................................................... 6 1.3 Peamised arengutegurid ja väljakutsed .................................... 12 2 Toimekeskkonna ülevaade ................................................. 14 2.1 Üldised valitsussektori teenused ............................................... 14 2.1.1 Valla juhtimine ..................................................................................... 14 2.1.2 Avalik ruum .......................................................................................... 17 2.2 Avalik kord ja julgeolek .............................................................. 19 2.3 Majandus ................................................................................... 20 2.3.1 Energiamajandus ................................................................................. 20 2.3.2 Teed ja tänavavalgustus ...................................................................... 21 2.3.3 Ühistransport ...................................................................................... -

Eesti Vabariigi 1919. Aasta Maareform Kohila Vallas

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Tartu University Library Tartu Ülikooli avatud ülikool Filosoofiateaduskond Ajaloo – ja arheoloogia instituut Ene Holsting EESTI VABARIIGI 1919. AASTA MAAREFORM KOHILA VALLAS Magistritöö Juhendaja: professor Tiit Rosenberg Tartu 2013 Sisukord SISSEJUHATUS ................................................................................................................................................... 3 1. MAASEADUSEST EESTIS ........................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 MAASEADUST ETTEVALMISTAV TEGEVUS........................................................................................... 7 1.2 MAASEADUSE VASTUVÕTMINE JA MAADE VÕÕRANDAMINE ............................................................... 9 1.3 VÕÕRANDATUD MAADE EEST TASU MAKSMINE ................................................................................ 10 1.4 RIIGIMAADE KASUTAMINE ................................................................................................................ 12 1.5 MAADE ERASTAMISE KÜSIMUS ......................................................................................................... 14 1.6 ERARENDIMAADE KORRALDAMINE ................................................................................................... 14 2. KOHILA VALD ........................................................................................................................................ -

City Break 100 Free Offers & Discounts for Exploring Tallinn!

City Break 100 free offers & discounts for exploring Tallinn! Tallinn Card is your all-in-one ticket to the very best the city has to offer. Accepted in 100 locations, the card presents a simple, cost-effective way to explore Tallinn on your own, choosing the sights that interest you most. Tips to save money with Tallinn Card Sample visits with Normal 48 h 48 h Tallinn Card Adult Tallinn Price Card 48-hour Tallinn Card - €32 FREE 1st Day • Admission to 40 top city attractions, including: Sightseeing tour € 20 € 0 – Museums Seaplane Harbour (Lennusadam) € 10 € 0 – Churches, towers and town wall – Tallinn Zoo and Tallinn Botanic Garden Kiek in de Kök and Bastion Tunnels € 8,30 € 0 – Tallinn TV Tower and Seaplane Harbour National Opera Estonia -15% € 18 € 15,30 (Lennusadam) • Unlimited use of public transport 2nd Day • One city sightseeing tour of your choice Tallinn TV Tower € 7 € 0 • Ice skating in Old Town • Bicycle and boat rental Estonian Open Air Museum with free audioguide € 15,59 € 0 • Bowling or billiards Tallinn Zoo € 5,80 € 0 • Entrance to one of Tallinn’s most popular Public transport (Day card) € 3 € 0 nightclubs • All-inclusive guidebook with city maps Bowling € 18 € 0 Total cost € 105,69 € 47,30 DISCOUNTS ON *Additional discounts in restaurants, cafés and shops plus 130-page Tallinn Card guidebook • Sightseeing tours in Tallinn and on Tallinn Bay • Day trips to Lahemaa National Park, The Tallinn Card is sold at: the Tallinn Tourist Information Centre Naissaare and Prangli islands (Niguliste 2), hotels, the airport, the railway station, on Tallinn-Moscow • Food and drink in restaurants, bars and cafés and Tallinn-St. -

Viimsi Valla Mandriosa Üldplaneeringu Teemaplaneeringu ”Miljööväärtuslikud Alad Ja Rohevõrgustik” Keskkonnamõju Strateegiline Hindamine

VIIMSI VALLA MANDRIOSA ÜLDPLANEERINGU TEEMAPLANEERINGU ”MILJÖÖVÄÄRTUSLIKUD ALAD JA ROHEVÕRGUSTIK” KESKKONNAMÕJU STRATEEGILINE HINDAMINE ARUANNE MTÜ Keskkonnakorraldus Telliskivi 40-1 10611 Tallinn Tel. 52 25011, 656 0302 [email protected] www.keskkonnakorraldus.ee Tallinn 2009 SISUKORD KOKKUVÕTE .................................................................................................................................................... 1 SISSEJUHATUS ................................................................................................................................................. 3 1 TEEMAPLANEERINGU JA KESKKONNAMÕJU STRATEEGILISE HINDAMISE EESMÄRGID ............................ 4 2 ÜLEVAADE PÕHJUSTEST, MILLE ALUSEL VALITI ALTERNATIIVSED ARENGUSTSENAARIUMID, MIDA PLANEERINGU KOOSTAMISEL KÄSITLETI .......................................................................................................... 5 3 KAVANDATAV TEGEVUS JA SELLE REAALSED ALTERNATIIVID .................................................................. 6 3.1 0-ALTERNATIIV .......................................................................................................................................... 6 3.2 1.-ALTERNATIIV ......................................................................................................................................... 7 3.3 2.-ALTERNATIIV ....................................................................................................................................... 13 4 PLANEERINGU JAOKS -

Läänepoolne Kaugeim Maatükk on Lindude Käsutu- Peenemat, Aga Eks Nad Pea Enne Kasvama, Kui Neist Ses Olev Nootamaa Läänemere Avaosas Ja Põhja Pool, Rääkima Hakatakse

Väikesaared Väikesaartel asuvad Eesti maismaalised äärmuspunk- Ruilaidu, Ahelaidu, Kivilaidu ja Viirelaidu. On ka peoga tid: läänepoolne kaugeim maatükk on lindude käsutu- peenemat, aga eks nad pea enne kasvama, kui neist ses olev Nootamaa Läänemere avaosas ja põhja pool, rääkima hakatakse. Soome lahes on selleks tuletornisaar Vaindloo. Saarte eripalgelisus ja mitmekesisus olenevad enamasti Eesti suuremaid saari – 2,6 tuhande ruutkilomeet- nende pindalast ja kõrgusest, kuid ka geomorfoloogili- rist Saaremaad ja tuhande ruutkilomeetri suurust sest ehitusest, pärastjääaegsest maakerkest, randade Hiiumaad teatakse laialt, Muhumaad ja Vormsit samuti. avatusest tuultele ja tormilainele jm. Saare tuum on Väiksematega on lugu keerulisem ja teadmised juhus- enamasti aluspõhjaline või mandrijää toimel tekkinud likumad. Siiski ei vaidle keegi vastu, et väikesaared on kõrgendik, mida siis meri omasoodu on täiendanud või omapärane, põnev ja huvipakkuv nähtus. kärpinud. Saare maastiku kujunemisel on oluline tema Väikesaarte arv muutub pidevalt, kuna kiirusega ligi pinnamoe liigestatus. Keerukama maastikuga saared 3 mm aastas kerkiv maapind kallab paljudes kohtades on tekkinud mitme väikesaare liitumisel. Tavaliselt on endalt merevee, kogub pisut lainete või hoovuste too- kõrgem saar ka vanem, aga tugevad kõrgveega tormid dud setteid ja moodustab ikka uusi ja uusi saarekesi. korrigeerivad seda reeglit, kuhjates saare vanematele Teisest küljest kipuvad nii mõnedki vanasti eraldi olnud osadele uusi nooremaid rannavalle. Vanimaks väike- saared nüüd sellesama meretõusu, setete kuhjumise ja saareks Eesti rannikumeres peetakse Ruhnut, mis võis Rand-ogaputk veetaimede vohamise tõttu üksteisega kokku kasvama. saarena üle veepinna tõusta juba Joldiamere taandu- misel üle 10 000 aasta tagasi. Sealsed vanimad ranna- Erinvatel kaartidel on saarte arv erinev. Peamiselt mui- vallid on moodustunud Antsülusjärve staadiumil juba dugi mõõtkava pärast. -

Wave Exposure Calculations for the Gulf of Finland

Wave exposure calculations for the Gulf of Finland Felix van der Meijs and Martin Isaeus AquaBiota Water Research 1 Wave Exposure for the Gulf of Finland S TOC K H OLM , D e c e m b e r 2020 Client: Performed by AquaBiota Water Research, for the Estonian Marine Institute at the University of Tartu. Authors: Felix van der Meijs ([email protected]) Martin Isaeus ([email protected]) Contact information: AquaBiota Water Research AB Address: Sveavägen 159, SE-113 46 Stockholm, Sweden Phone: +46 8 522 302 40 Web page: www.aquabiota.se Quality control/assurance: Martin Isaeus Internet version: Downloadable at www.aquabiota.se Cite as: van der Meijs, F. & Isaeus, M. 2020. Wave exposure calculations for the Gulf of Finland AquaBiota Water Research, AquaBiota Report 2020:13. 32 pages AquaBiota Report 2020:13 AquaBiota Projektnummer: 2020013 ISBN: 978-91-89085-22-0 ISSN: 1654-7225 © AquaBiota Water Research 2020 2 CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 5 2. METHODS AND MATERIALS ............................................................................ 6 2.1. Land/Sea grids........................................................................................... 6 2.2. Fetch calculations ..................................................................................... 8 2.3. Wind data............................................................................................... -

International Geological Congress, XXVII Session, Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic, Excursions: 027, 028 Guidebook

INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGICAL CONGRESS XXVII SESSION ESTONIAN SOVIET SOCIAL1ST REPUBLIC Excursions: 027, 028 Guidebook 021 A +e \ \ �� Dz \ _(,/ \ POCCHHCKAR Ct/JCP\ RUSsiAN SFSR \ y n] Dt (. - � v$&.1/ATBHHCKA f1 CCP LATV/AN SSR 02 • 3 INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGICAL CONGRESS XXVII SESSION USSR MOSCOW 1984 ESTONIAN SOVIET SOCIAL1ST REPUBLIC Excursions: 027 Hydrogeology of the Baltic 028 Geology and minerai deposits of Lower Palaeozoic of the Eastern Baltic area Guidebook Tallinn, 1984 552 G89 Prepared for the press by Institute of Geology, Academy of Sciences of the Estonian SSR and Board of Geology of the Estonian SSR Editorial board: D. Kaljo, E. Mustjõgi and I. Zekcer Authors of the guide: A. Freimanis, ü. Heinsalu, L. Hints, P. Jõgar, D. Kaljo, V. Karise, H. Kink, E. Klaamann, 0. Morozov, E. Mustjõgi, S. Mägi, H. Nestor, Y. Nikolaev, J. Nõlvak, E. Pirrus, L. Põlma, L. Savitsky, L. Vallner, V. Vanchugov Перевод с русского Титул оригинала: Эстонская советехая сочиалистичесхая Республика. Экскурсии: 027, 028. Сводный путеводителъ. Таллии, 1984. © Academy of Sciences of the Estonian SSR, 1984 INTRODUCTION The geology of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic (Estonia) has become the object of excursions of the International Geo logical Congress for the second time. It happened first in 1897 when the excursion of IGC visited North Estonia (and the ter ritory of the present Leningrad District) under the guidance of Academician F. Schmidt. Such recurrent interest is justi fied in view of the classical development of the Lower Pa laeozoic in our region and the results of investigations ohtained by geological institutions of the republic. The excursions of the 27th IGC are designed, firstly, to provide a review of the stratigraphy, palaeontology and lithology of the Estonian Early Palaeozoic and associated useful minerals in the light of recent investigations (excursion 028), and, secondly, to give a survey of the problerus and some results of hydrogeology in a mare extensive area of the northwestern part of the Soviet Union (excursion 027). -

Tööpuudus Rekordiliselt Väike

Äripäeva online-uudised: valuutakursid 23.08. www.aripaev.ee kolumn USD 12,21 EEK Eestlane kardab uusi tuuli EUR 1,28 USD Eestlaste seas on võtnud võimust mure SEK 1,70 EEK igapäevase elu- ga toimetuleku ÄP indeks 23.08. pärast ja hirm muutuste ees, Toomas leiab teoloog Paul 1829,26 0,53% Toomas Paul. lk 19 NELJAPÄEV • 24. august 2006 • nr 150 (3165) • hind 16 kr LLõheõhe LLHVsHVs LHV senised partnerid ees- otsas Rain Tammega võta- vad endale kasumlikuma tüki firmast ja jätavad vähe- kasumlikud üksused Rain Lõhmusele, keda USA väärt- paberijärelevalve seostab ebaseaduslike aktsiatehingu- tega. lk 2–3, 18 Fotod: Raul Mee, Maris Ojasuu Kristjan Järvik tahab VASE HIND TÕUSNUD ENAM Tööpuudus teha põlevkiviõlitehast Parkimisprotsess KUI POOLE VÕRRA jõuab lõpule vasetonni hind dollarites rekordiliselt väike Eesti väikeärimees Kristjan 7620 Järvik peab läbirääkimisi Eilne kohtuistung Tallinna 23.08.2006 8800 Ettevõtjate sõnul USA gaasi- ja naftauuringute parkimiskonkursi tulemuste 7600 viib ülimadal töö- firmaga Mobilestream Oil, et üle kestis enam kui neli tundi. puudus majandus- Otsuse, kas Falck sai võidu 6400 ehitada Eestisse suur põlevki- kasvu aeglustumi- viõlitehas. lk 4 õiglasel viisil, langetab kohus 5200 seni, kui riik võõr- septembri algul. lk 8 4000 tööjõu sissetoomist 01.03.2006 23.08.2006 oluliselt ei lihtsusta. Valimisvõitlus Rootsis Allikas: Bloomberg “Oma tööjõuga hoogustub Äripäev maakonnas jääme vintsklema,” Rootsi parempoolsed luba- Vase hind tõusnud nendib Personali- vad valimisvõidu korral alus- Võrumaa TOPi võitja Lapi MT punkt Extra tegev- tada massilise riigifirmade leevendab tööjõupuudust teh- poole võrra juht Herdis Ojasu. erastamisega. lk 6 noloogiasse investeerides. Kuue kuuga enam kui poole lk 5 lk 14 võrra tõusnud vase hind on kaevandusfirmade aktsiad at- Tallinn kulutab raktiivseks muutnud. -

Baltic Coastal Hiking Route

BALTIC COASTAL HIKING ROUTE TOURS WWW.COASTALHIKING.EU LATVIA / ESTONIA TOURS WHAT CAN YOU FIND 11 12 IN THE BROCHURE TABLE OF CONTENTS TALLINN 10 The brochure includes 15 hiking tours for one and multiple days (up to 16 days) in 13 Latvia and Estonia, which is part of the Baltic Coastal Hiking Route long distance 9 path (in Latvia - Jūrtaka, in Estonian - Ranniku matkarada) (E9) - the most WHAT CAN YOU COASTAL NATURE 1. THE ROCKY 2. THE GREAT 3. sLĪtere 4. ENGURE ESTONIA interesting, most scenic coastal areas of both countries, which are renowned for FIND IN THE IN LATVIA AND BEACH OF VIDZEME: WAVE SEA NATIONAL PARK NATURE PARK their natural and cultural objects. Several tours include national parks, nature BROCHURE ESTONIA Saulkrasti - Svētciems liepāja - Ventspils Mazirbe - Kolka Mērsrags - Engure SAAREMAA PÄRNU parks, and biosphere reserves, as well as UNESCO World Heritage sites. 3 p. 8 7 Every tour includes schematic tour map, provides information about the mileage to be covered within a day, level of di culty, most outstanding sightseeing objects, as GETTING THERE 2days km 6 days km 1 day km 1 day km KOLKA well as practical information about the road surface, getting to the starting point and & AROUND 52 92 23 22 3 SALACGRĪVA returning from the fi nish back to the city. USEFUL 1 p. LINKS 4 p. LATVIA 5 p. LATVIA 7 p. LATVIA 10 p. LATVIA 11 p. 1 The tours are provided for both individual travellers and small tourist groups. VENTSPILS 6 4 It is recommended to book the transport (rent a car or use public transportation), SKULTE 5 accommodation and meals in advance, as well as arrange personal and luggage 5. -

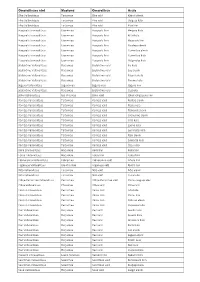

Omavalitsuse Nimi Maakond Omavalitsus Asula Elva

Omavalitsuse nimi Maakond Omavalitsus Asula Elva Vallavalitsus Tartumaa Elva vald Käärdi alevik Elva Vallavalitsus Tartumaa Elva vald Valguta küla Elva Vallavalitsus Tartumaa Elva vald Elva linn Haapsalu Linnavalitsus Läänemaa Haapsalu linn Herjava küla Haapsalu Linnavalitsus Läänemaa Haapsalu linn Kiltsi küla Haapsalu Linnavalitsus Läänemaa Haapsalu linn Haapsalu linn Haapsalu Linnavalitsus Läänemaa Haapsalu linn Paralepa alevik Haapsalu Linnavalitsus Läänemaa Haapsalu linn Uuemõisa alevik Haapsalu Linnavalitsus Läänemaa Haapsalu linn Uuemõisa küla Haapsalu Linnavalitsus Läänemaa Haapsalu linn Valgevälja küla Jõelähtme Vallavalitsus Harjumaa Jõelähtme vald Iru küla Jõelähtme Vallavalitsus Harjumaa Jõelähtme vald Loo alevik Jõelähtme Vallavalitsus Harjumaa Jõelähtme vald Maardu küla Jõelähtme Vallavalitsus Harjumaa Jõelähtme vald Neeme küla Jõgeva Vallavalitsus Jõgevamaa Jõgeva vald Jõgeva linn Jõelähtme Vallavalitsus Harjumaa Jõelähtme vald Uusküla Jõhvi Vallavalitsus Ida-Virumaa Jõhvi vald Jõhvi vallasisene linn Kambja Vallavalitsus Tartumaa Kambja vald Külitse alevik Kambja Vallavalitsus Tartumaa Kambja vald Reola küla Kambja Vallavalitsus Tartumaa Kambja vald Tõrvandi alevik Kambja Vallavalitsus Tartumaa Kambja vald Ülenurme alevik Kambja Vallavalitsus Tartumaa Kambja vald Uhti küla Kambja Vallavalitsus Tartumaa Kambja vald Laane küla Kambja Vallavalitsus Tartumaa Kambja vald Lemmatsi küla Kambja Vallavalitsus Tartumaa Kambja vald Räni alevik Kambja Vallavalitsus Tartumaa Kambja vald Soinaste küla Kambja Vallavalitsus Tartumaa Kambja -

Estonia Estonia

Estonia A cool country with a warm heart www.visitestonia.com ESTONIA Official name: Republic of Estonia (in Estonian: Eesti Vabariik) Area: 45,227 km2 (ca 0% of Estonia’s territory is made up of 520 islands, 5% are inland waterbodies, 48% is forest, 7% is marshland and moor, and 37% is agricultural land) 1.36 million inhabitants (68% Estonians, 26% Russians, 2% Ukrainians, % Byelorussians and % Finns), of whom 68% live in cities Capital Tallinn (397 thousand inhabitants) Official language: Estonian, system of government: parliamen- tary democracy. The proclamation of the country’s independ- ence is a national holiday celebrated on the 24th of February (Independence Day). The Republic of Estonia is a member of the European Union and NATO USEFUL INFORMATION Estonia is on Eastern European time (GMT +02:00) The currency is the Estonian kroon (EEK) ( EUR =5.6466 EEK) Telephone: the country code for Estonia is +372 Estonian Internet catalogue www.ee, information: www.1182.ee and www.1188.ee Map of public Internet access points: regio.delfi.ee/ipunktid, and wireless Internet areas: www.wifi.ee Emergency numbers in Estonia: police 110, ambulance and fire department 112 Distance from Tallinn: Helsinki 85 km, Riga 307 km, St. Petersburg 395 km, Stockholm 405 km Estonia. A cool country with a warm heart hat is the best expression of Estonia’s character? Is an extraordinary building of its own – in the 6th century Wit the grey limestone, used in the walls of medieval Oleviste Church, whose tower is 59 metres high, was houses and churches, that pushes its way through the the highest in the world.