Hoehler Knowledges 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One of Deep Ocean's Most Turbulent Areas Has Big Impact on Climate 9 August 2007

One of Deep Ocean's Most Turbulent Areas Has Big Impact on Climate 9 August 2007 small passageways of such mountains is generating much of the mixing of warm and cold waters in the Atlantic Ocean. Better understanding of the mechanisms of mixing is crucial, says St. Laurent, an assistant professor of physical oceanography at FSU and the study’s co-principal investigator, because mixing produces the overall balance of water temperatures that helps control the strength of the Gulf Stream -- the strong, warm ocean current that starts in the Gulf of Mexico, flows along the U.S. east coast to Canada and on to Europe, and plays a crucial climate role. “Oceanographers are working hard to understand how processes in the ocean help to keep the Earth’s climate stable,” St. Laurent said. “We are aware that the climate is warming, but we don’t yet fully understand how the changes will affect Profiler. Credit: Florida State University society. Our work will result in better models for predicting how the ocean will affect the climate in the future and a better understanding of sea-level rise, weather patterns such as El Nino, and the More than a mile beneath the Atlantic’s surface, impact of these events on fisheries.” roughly halfway between New York and Portugal, seawater rushing through the narrow gullies of an St. Laurent compared the flow of seawater through underwater mountain range much as winds gust underwater gullies in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge to the between a city’s tall buildings is generating one of wind, so familiar to hikers, that blows through the most turbulent areas ever observed in the deep mountain passages on land. -

A Comprehensive Geospatial Assessment of Seagrass Distribution in India

Ocean and Coastal Management xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ocean and Coastal Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ocecoaman A comprehensive geospatial assessment of seagrass distribution in India ∗ Gejo Anna Geevarghese , B. Akhil, G. Magesh, P. Krishnan, R. Purvaja, R. Ramesh National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management (NCSCM), Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, Anna University Campus, Chennai 600025, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The study deals with the first comprehensive spatial distribution and area estimate of seagrass patches of India Area estimate with a standardized methodology. Seagrass patches are mainly located in Palk Bay – Gulf of Mannar (Tamil Landsat 8 OLI Nadu), Gulf of Kachchh (Gujarat), Chilika Lake (Odisha) and Islands of Andaman & Nicobar and Lakshadweep. fi Digital classi cation Medium resolution satellite images of Landsat 8 OLI were subjected to radiometric, atmospheric and water Seagrass column correction prior to digital classification and contextual editing. Total estimated seagrass area amounts to Water column correction 516.59 km2 of which Palk Bay and Gulf of Mannar of Tamil Nadu together contribute to 398.81 km2. Overall classification accuracy for the six sites studied, ranged between 64% (Lakshadweep Islands) and 83.5% (Palk Bay). This suggests that for surveillance studies of homogeneous seagrass meadows with low interspersion of other benthic units such as corals, seaweeds etc., digital mapping using medium resolution data sets with mandatory attenuation correction procedures is suitable. The results of this study and the related area statistics were accepted as a baseline at national level for the delineation of Ecologically Sensitive Areas (ESA) and in the formulation of its conservation strategies. -

When the Earth Moves Seafloor Spreading and Plate Tectonics

This article was published in 1999 and has not been updated or revised. BEYONDBEYOND DISCOVERYDISCOVERYTM THE PATH FROM RESEARCH TO HUMAN BENEFIT WHEN THE EARTH MOVES SEAFLOOR SPREADING AND PLATE TECTONICS arly on the morning of Wednesday, April 18, the fault had moved, spanning nearly 300 miles, from 1906, people in a 700-mile stretch of the West San Juan Bautista in San Benito County to the south E Coast of the United States—from Coos Bay, of San Francisco to the Upper Mattole River in Oregon, to Los Angeles, California—were wakened by Humboldt County to the north, as well as westward the ground shaking. But in San Francisco the ground some distance out to sea. The scale of this movement did more than shake. A police officer on patrol in the was unheard of. The explanation would take some six city’s produce district heard a low rumble and saw the decades to emerge, coming only with the advent of the street undulate in front of him, “as if the waves of the theory of plate tectonics. ocean were coming toward me, billowing as they came.” One of the great achievements of modern science, Although the Richter Scale of magnitude was not plate tectonics describes the surface of Earth as being devised until 1935, scientists have since estimated that divided into huge plates whose slow movements carry the the 1906 San Francisco earthquake would have had a continents on a slow drift around the globe. Where the 7.8 Richter reading. Later that morning the disaster plates come in contact with one another, they may cause of crushed and crumbled buildings was compounded by catastrophic events, such as volcanic eruptions and earth- fires that broke out all over the shattered city. -

Features of the Natural Environment and Modern Economy

Japan – features of the natural environment and modern economy Japan – features of the natural environment and modern economy Lesson plan (Polish) Lesson plan (English) Japan – features of the natural environment and modern economy Link to the lesson Before you start you should know that on Earth, in places where there is contact between lithospheric plates, there are seismic phenomena and active volcanoes; what the consequences of earthquakes can be and the destruction caused by undersea volcanic eruptions; which types of climate occur in Asia; that socio‐cultural factors play a vital role in the development of a country and its institutions. You will learn to determine the location of the Japanese archipelago and read the names of the largest of its islands; to identify the natural threats occuring in the area of East Asia which shape the natural environment of the Japanese archipelago; to name the ways people adapt to the natural threats (earthquakes, typhoons and tsunamis) in Japan; to identify the importance of social and cultural factors in the creation of Japan's modern economy. Nagranie dostępne na portalu epodreczniki.pl nagranie abstraktu Task 1 Think, and write your conclusions. What influences Japan's variations in climate? Japan's natural environment – threats and limitaons to selement and economic development The Japanese archipelago stretches in the shape of an arch with a length of approximately 2.5 km along the East coast of Asia, from the North‐East to the South‐West. Its main part is made up of 4 large islands – Hokkaido, Honsiu, Kiusiu and Sikoku – separated from Asia by the Sea of Japan, and from the West, surrounded by the open waters of the Pacific Ocean. -

Ocean Surface Topography Mission/ Jason 2 Launch

PREss KIT/JUNE 2008 Ocean Surface Topography Mission/ Jason 2 Launch Media Contacts Steve Cole Policy/Program Management 202-358-0918 Headquarters [email protected] Washington Alan Buis OSTM/Jason 2 Mission 818-354-0474 Jet Propulsion Laboratory [email protected] Pasadena, Calif. John Leslie NOAA Role 301-713-2087, x174 National Oceanic and [email protected] Atmospheric Administration Silver Spring, Md. Eliane Moreaux CNES Role 011-33-5-61-27-33-44 Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales [email protected] Toulouse, France Claudia Ritsert-Clark EUMETSAT Role 011-49-6151-807-609 European Organisation for the [email protected] Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites Darmstadt, Germany George Diller Launch Operations 321-867-2468 Kennedy Space Center, Fla. [email protected] Contents Media Services Information ...................................................................................................... 5 Quick Facts .............................................................................................................................. 7 Why Study Ocean Surface Topography? ..................................................................................8 Mission Overview ....................................................................................................................13 Science and Engineering Objectives ....................................................................................... 20 Spacecraft .............................................................................................................................22 -

Using Radar Altimeter Backscatter to Evaluate Ice Cover on the Yukon River

Using radar altimeter backscatter to evaluate ice cover on the Yukon River Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Research Distinction in Earth Sciences in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Stephen P. Coss The Ohio State University August 2015 Project Advisor: Professor Michael T. Durand, School of Earth Sciences Table of Contents Abstract.............................................................................................................................................ii Acknowledgments..............................................................................................................................................iii List of Figures.....................................................................................................................................................iv List of Tables......................................................................................................................................................iv List of Equations................................................................................................................................................iv Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................1 Objectives.............................................................................................................................................................2 Study -

Cryosat Baseline-C Ocean Product Handbook

esrin Largo Galileo Galilei, 1 Casella Postale 64 00044 Frascati, Italy T +39 06 9418 01 F +39 06 9418 0280 www.esa.int Version 4.1 5th December 2019 Baseline-C CryoSat Ocean Processor Ocean Product Handbook Prepared by F. Mertz, JP Dumont and S Urien (CLS) CryoSat Ocean Processor developers Approved by: J. Bouffard (ESA - ESRIN) CryoSat Data Quality Manager P. Féménias (ESA - ESRIN CryoSat ESA Technical Officer CryoSat Ocean Product Handbook V 4.1 i.1 Chronology Issues: Issue: Date: Reason for change: Author 1.0 26/04/13 Creation F. Mertz JP Dumont S Urien 2.0 10/06/13 Update for AR F. Mertz 3.0 27/10/17 Update for Cryosat-2 Ocean Processing Baseline C S Urien (CONFORM, SAMOSA, update of geophysical models) 4.0 05/12/17 ESA final review and update J. Bouffard 4.1 05/12/19 Update to account for POE-F orbit solution S. Urien Index Sheet: Context: Keywords: CryoSat, Satellite Altimetry, Ocean product, Baseline C Hyperlink: Distribution: Company Means of distribution Names CLS Notification J.P. Dumont S. Urien ACS Electronic Copy P.L. Mantovani ESA Electronic Copy J. Bouffard P. Féménias Applicable documents CryoSat Ocean Product Handbook V 4.1 i.2 AD 1 IPF Cryosat Ocean Products Contract Change Notice C2-CN-ACS-GS-5309 AD 2 Earth Explorer Ground Segment File Format Standard PE-TN-ESA-GS-0001 AD 3 IOP & GOP Product Format Specification Products format specification [COP-FMT], CS-RS-ACS-GS-5213 1rev4, https://earth.esa.int/documents/10174/125273/CryoSat-L1b-L2-Ocean- NetCDF-product-format-specification.pdf AD 4 CryoSat Ocean NetCDF Product Format Specification (L1b&L2) [PFS-OCE] CS-RS-ACS-ESL-5266 3rev1 AD 5 CryoSat Baseline D Product Handbook, 2019: https://earth.esa.int/documents/10174/125272/CryoSat-Baseline-D-Product- Handbook Reference documents RD 1 Bouffard, J., M. -

Census of Marine Life Research Plan (Version 2005)

CENSUS Research Plan OF MARINE LIFE Version January 2005 Nematoda Porifera Arthropoda Mollusca Cnidaria Annelida Platyhelminthes Echinodermata Chordata Cover Images Annelida: Marine polychaete, Polychaeta (Serpulidae). Photo: Sea Studios Foundation, Monterey, CA. Arthropoda: Armed hermit crab, Pagurus armatus. Photo: Doug Pemberton Chordata: Orbicular burrfish, Cyclichthys orbicularis (Diodontidae). Photo: Karen Gowlett-Holmes Cnidaria: Horned stalked jellyfish, Lucernaria quadricornis. Photo: Strong/Buzeta Echinodermata: Daisy brittle star, Ophiopholis aculeata, Photo: Dann Blackwood Mollusca: Deep-sea scallop, Placopecten magellanicus. Photo: Dann Blackwood Nematoda: Non-segmented nematode, Pselionema sp. Photo: Thomas Buchholz, Institute of Marine Biology, Crete Platyhelminthes: Unidentified pseudocerotid flatworm. Photo: Brian Smith Porifera: Stove-pipe sponge, Aplysina archeri. Photo: Shirley Pomponi The Census of Marine Life Research Plan is written and distrib- uted by the Census of Marine Life International Secretariat. It has undergone several iterations of review by the International Scientific Steering Committee, chairs of national and regional implementa- tion committees, and the leadership of OBIS, HMAP, FMAP, and the Ocean Realm Field Projects. Census of Marine Life Research Plan, Version January 2005 The Census of Marine Life Executive Summary In a world characterized by crowded shorelines, oceanic pollution, and exhausted fisheries, only an encompassing global marine census can probe the realities of the declines or global -

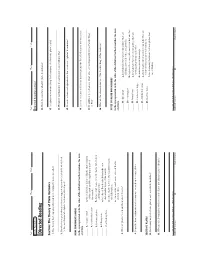

Directed Reading Continued

Name Class Date Name Class Date Skills Worksheet Directed Reading continued Directed Reading 12. How do scientists identify plate boundaries? Section: The Theory of Plate Tectonics 13. A sudden movement along the boundary of a tectonic plate is a(n) 1. The theory that explains why and how continents move is called ___________________________________________________________________. ___________________________________________________________________. 14. Frequent earthquakes in a given zone are evidence that 2. By what time period was evidence supporting continental drift, which led to the development of plate tectonics, developed? 15. How do volcanoes help identify the locations of plates boundaries? HOW CONTINENTS MOVE In the space provided, write the letter of the definition that best matches the term 16. A zone of active volcanoes that encircles the Pacific Ocean is known as the or phrase. ___________________________________________________________________. ______ 3. oceanic crust a. the solid outer layer of Earth, that consists of the crust and the rigid upper part of 17. In addition to volcanoes, what also occurs frequently in the Pacific Ring ______ 4. continental crust the mantle of Fire? ______ 5. tectonic plates b. dense crust made of rock that is rich in iron and magnesium ______ 6. lithosphere 18. What do the characteristics of the Pacific Ring of Fire indicate? c. blocks of Earth’s shell that ride on a ______ 7. asthenosphere deformable layer of the mantle d. solid, plastic layer of the mantle beneath the lithosphere TYPES OF PLATE BOUNDARIES e. low-density crust made of rock that is In the space provided, write the letter of the definition that best matches the term rich in silica or phrase. -

R E B E C Ca W a L S H D E

WAVES AND CURRENTS Powerful Currents in Deep-Sea Gorges HY P What energy drives these currents in hundreds of seafloor ‘Grand Canyons’? GRA O n my first major research cruise, than the ship extending to the horizon comes from, what form it takes, how it is the ship was hit by a hurricane. in every direction. We bobbed haplessly transformed—is central to my work as a OnO the second, the weather was even among them. At a time like that, it’s hard graduate student at Woods Hole Oceano- worse. In one particularly nasty storm, not to feel philosophical about the power graphic Institution. In my case, it is the I remember standing braced on the of nature. energy that controls currents in the deep ship’s bridge late at night, watching In a very different context, the power ocean and ultimately influences the ocean’s bolts of lightning light up the world. of nature is something I spend a lot of my global circulation. Each one revealed waves taller time thinking about. Energy—where it I research the way the shape of the PHYSICAL OCEAN WALSH DELL The seafloor is filled with thousands of deep can- yons, where powerful currents appear to be flowing uphill along the canyon floors. These currents could play a major role in driving global ocean circulation. REBECCA REBECCA 44 Oceanus MagaZIne Vol. 49, No. 1, Winter 2011 | www.whoi.edu/oceanus ocean floor affects the ocean’s circulation. previously unknown role. giant range of mountains that runs More particularly, I explore the fundamen- Concealed from our view, the bottom from Iceland nearly to Antarctica and tal physics that transforms energy, drives of the ocean is covered with mountains covers about half the bottom of the currents, and mixes up water masses in the and canyons far larger and steeper than Atlantic Ocean. -

Rocks and Geology in the San Francisco Bay Region

Rocks and Geology in the San Francisco Bay Region ������� ����� ��������� �������� ���� ������ ��� ��������� �������� ��������� �������� ������ ������ ������ ����� ����� ������ ����������� ����� ����������� ����� ��������� ������������ ���� ���� ������� ���� ������ ���� ������� �������� ������ ��� ����� �� ����� ������ ��� ����� ������ Bulletin 2195 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey This page intentionally left blank Rocks and Geology in the San Francisco Bay Region By Philip Stoffer Bulletin 2195 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey 1 U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2002 Electronic copies of this publication are available online at http://geopubs.wr.usgs.gov/bulletin/b2195/ Additional USGS publications can be found online at http://geology.usgs.gov/products.html For more information about the USGS and its products: Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS (1–888–275–8747) World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Published in the Western Region, Menlo Park, California Manuscript approved for publication, September 30, 2002 Text and illustrations edited by James W. Hendley II Production and design by Susan Mayfield III Contents Introduction.............................................................................................................................................................. -

Concept Review

Name Class Date Skills Worksheet Concept Review In the space provided, write the letter of the definition that best matches the term or phrase. ______ 1. Pangaea a. region along a plate boundary where one plate moves under another ______ 2. lithosphere b. piece of lithosphere with a unique ______ 3. rift valley geologic history c. crack in the center of a mid-ocean ridge ______ 4. sea-floor spreading d. supercontinent formed about 300 million ______ 5. paleomagnetism years ago residual magnetism of rock ______ 6. terrane e. f. process by which new sea floor forms ______ 7. mid-ocean ridge g. layer that forms the thin outer shell of Earth ______ 8. subduction zone h. cycle in which heated material rises and cooler material sinks ______ 9. continental drift i. undersea mountain range ______ 10. convection cell j. hypothesis that the continents once formed a single landmass In the space provided, write the letter of the answer choice that best completes each statement or best answers each question. ______ 11. What kind of fossil evidence supported Wegener’s hypothesis? a. fossils hinting at a land bridge between South America and Africa b. fossils proving Mesosaurus never lived in Africa c. plant fossils showing that cold areas used to be tropical d. sea fossils proving the continents had plowed through the ocean floor ______ 12. Sea-floor spreading was a key discovery because it showed a. that mid-ocean ridges exist. b. how continents move. c. why some rocks have reversed polarity. d. that mid-ocean ridges have rifts at the center.