Modeling Morality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections on the Evolution of Morality Christine M. Korsgaard

Reflections on the Evolution of Morality Christine M. Korsgaard Harvard University1 All instincts that do not discharge themselves outwardly turn inward – this is what I call the internalization of man: thus it was that man first developed what was later called his “soul.” The entire inner world, originally as thin as if it were stretched between two membranes, expanded and extended itself, acquiring depth, breadth, and height, in the same measure as outward discharge was inhibited. - Nietzsche 1. Introduction In recent years there has been a fair amount of speculation about the evolution of morality, among scientists and philosophers alike. From both points of view, the question how our moral nature might have evolved is interesting because morality is one of the traditional candidates for a distinctively human attribute, something that makes us different from the other animals. From a scientific point of view, it matters whether there are any such attributes because of the special burden they seem to place on the theory of evolution. Beginning with Darwin’s own efforts in The Descent of Man, defenders of the theory of evolution have tried to show either that there are no genuinely distinctive human attributes – that is, that any differences between human beings and the other animals are a matter of degree – or that apparently distinctive human attributes can be explained in terms of the 1 Notes on this version are incomplete. Recommended supplemental reading: “The Activity of Reason,” APA Proceedings November 09, pp. 30-38. In a way, these papers are companion pieces, or at least their final sections are. -

Evolution and Ethics 2

It is still disputed, however, why moral behavior extends beyond a close circle of kin and reciprocal relationships: e.g., most people think stealing from anyone is wrong, not just stealing from family and friends. For moral behavior to evolve as we understand it today, there likely had to be selective pressures that pushed people to disregard their own 1000wordphilosophy.com/2018/10/11/evolution- interests in favor of their group’s interest.[3] Exactly and-ethics/ how morality extended beyond this close circle is debated, with many theories under consideration.[4] Evolution and Ethics 2. What Should We Do? Author: Michael Klenk Suppose our ability to understand and apply moral Category: Ethics, Philosophy of Science rules, as typically understood, can be explained by Word Count: 999 natural selection. Does evolution explain which rules We often follow what are considered basic moral we should follow?[5] rules: don’t steal, don’t lie, help others when we can. Some answer, “yes!” “Greed captures the essence of But why do we follow these rules, or any rules the evolutionary spirit,” says the fictional character understood as “moral rules”? Does evolution explain Gordon Gekko in the 1987 film Wall Street: “Greed why? If so, does evolution have implications for … is good. Greed is right.”[6] which rules we should follow, and whether we genuinely know this? Gekko’s claims about what is good and right and what we ought to be comes from what he thinks we This essay explores the relations between evolution naturally are: we are greedy, so we ought to be and morality, including evolution’s potential greedy. -

Redalyc.The New Science of Moral Cognition: the State of The

Anales de Psicología ISSN: 0212-9728 [email protected] Universidad de Murcia España Olivera-La Rosa, Antonio; Rosselló, Jaume The new science of moral cognition: the state of the art Anales de Psicología, vol. 30, núm. 3, septiembre-diciembre, 2014, pp. 1122-1128 Universidad de Murcia Murcia, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=16731690011 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative anales de psicología, 2014, vol. 30, nº 3 (octubre), 1122-1128 © Copyright 2014: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Murcia. Murcia (España) http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.166551 ISSN edición impresa: 0212-9728. ISSN edición web (http://revistas.um.es/analesps): 1695-2294 The new science of moral cognition: the state of the art Antonio Olivera-La Rosa1,2* y Jaume Rosselló1,3 1 Human Evolution and Cognition Group (IFISC-CSIC), University of the Balearic Islands, 07122 Palma de Mallorca (Spain) 2 Faculty of Psychology and Social Sciences. Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó, Medellín (Colombia) 3 Department of Psychology, University of the Balearic Islands, 07122 Palma de Mallorca (Spain) Título: La nueva ciencia de la cognición moral: estado de la cuestión. Abstract: The need for multidisciplinary approaches to the scientific study Resumen: La necesidad de realizar aproximaciones multidisciplinares al of human nature is a widely supported academic claim. This assumption estudio de la naturaleza humana es ampliamente aceptada. -

Mill's Conversion: the Herschel Connection

volume 18, no. 23 Introduction november 2018 John Stuart Mill’s A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive, being a connected view of the principles of evidence, and the methods of scientific investigation was the most popular and influential treatment of sci- entific method throughout the second half of the 19th century. As is well-known, there was a radical change in the view of probability en- dorsed between the first and second editions. There are three differ- Mill’s Conversion: ent conceptions of probability interacting throughout the history of probability: (1) Chance, or Propensity — for example, the bias of a bi- The Herschel Connection ased coin. (2) Judgmental Degree of Belief — for example, the de- gree of belief one should have that the bias is between .6 and .7 after 100 trials that produce 81 heads. (3) Long-Run Relative Frequency — for example, propor- tion of heads in a very large, or even infinite, number of flips of a given coin. It has been a matter of controversy, and continues to be to this day, which conceptions are basic. Strong advocates of one kind of prob- ability may deny that the others are important, or even that they make Brian Skyrms sense at all. University of California, Irvine, and Stanford University In the first edition of 1843, Mill espouses a frequency view of prob- ability that aligns well with his general material view of logic: Conclusions respecting the probability of a fact rest, not upon a different, but upon the very same basis, as conclu- sions respecting its certainly; namely, not our ignorance, © 2018 Brian Skyrms but our knowledge: knowledge obtained by experience, This work is licensed under a Creative Commons of the proportion between the cases in which the fact oc- Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. -

Evolution and the Social Contract

Evolution and the Social Contract BRIAN SKYRMS The Tanner Lectures on Human Values Delivered at Te University of Michigan November 2, 2007 Peterson_TL28_pp i-250.indd 47 11/4/09 9:26 AM Brian Skyrms is Distinguished Professor of Logic and Philosophy of Science and of Economics at the University of California, Irvine, and Pro- fessor of Philosophy and Religion at Stanford University. He graduated from Lehigh University with degrees in Economics and Philosophy and received his Ph.D. in Philosophy from the University of Pittsburgh. He is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the National Academy of Sciences, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. His publications include Te Dynamics of Rational Delibera- tion (1990), Evolution of the Social Contract (1996), and Te Stag Hunt and the Evolution of Social Structure (2004). Peterson_TL28_pp i-250.indd 48 11/4/09 9:26 AM DEWEY AND DARWIN Almost one hundred years ago John Dewey wrote an essay titled “Te In- fuence of Darwin on Philosophy.” At that time, he believed that it was really too early to tell what the infuence of Darwin would be: “Te exact bearings upon philosophy of the new logical outlook are, of course, as yet, uncertain and inchoate.” But he was sure that it would not be in provid- ing new answers to traditional philosophical questions. Rather, it would raise new questions and open up new lines of thought. Toward the old questions of philosophy, Dewey took a radical stance: “Old questions are solved by disappearing . while new questions . -

The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: on Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 12-2001 The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: On Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love Marc Bekoff University of Colorado Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_sata Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Behavior and Ethology Commons, and the Comparative Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Bekoff, M. (2001). The evolution of animal play, emotions, and social morality: on science, theology, spirituality, personhood, and love. Zygon®, 36(4), 615-655. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: On Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love Marc Bekoff University of Colorado KEYWORDS animal emotions, animal play, biocentric anthropomorphism, critical anthropomorphism, personhood, social morality, spirituality ABSTRACT My essay first takes me into the arena in which science, spirituality, and theology meet. I comment on the enterprise of science and how scientists could well benefit from reciprocal interactions with theologians and religious leaders. Next, I discuss the evolution of social morality and the ways in which various aspects of social play behavior relate to the notion of “behaving fairly.” The contributions of spiritual and religious perspectives are important in our coming to a fuller understanding of the evolution of morality. I go on to discuss animal emotions, the concept of personhood, and how our special relationships with other animals, especially the companions with whom we share our homes, help us to define our place in nature, our humanness. -

Ten Great Ideas About Chance a Review by Mark Huber

BOOK REVIEW Ten Great Ideas about Chance A Review by Mark Huber Ten Great Ideas About Chance Having had Diaconis as my professor and postdoctoral By Persi Diaconis and Brian Skyrms advisor some two decades ago, I found the cadences and style of much of the text familiar. Throughout, the book Most people are familiar with the is written in an engaging and readable way. History and basic rules and formulas of prob- philosophy are woven together throughout the chapters, ability. For instance, the chance which, as the title implies, are organized thematically rather that event A occurs plus the chance than chronologically. that A does not occur must add to The story begins with the first great idea: Chance can be 1. But the question of why these measured. The word probability itself derives from the Latin rules exist and what exactly prob- probabilis, used by Cicero to denote that “...which for the abilities are, well, that is a question most part usually comes to pass” (De inventione, I.29.46, Princeton University Press, 2018 Press, Princeton University ISBN: 9780691174167 272 pages, Hardcover, often left unaddressed in prob- [2]). Even today, modern courtrooms in the United States ability courses ranging from the shy away from assigning numerical values to probabilities, elementary to graduate level. preferring statements such as “preponderance of the evi- Persi Diaconis and Brian Skyrms have taken up these dence” or “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Those dealing with questions in Ten Great Ideas About Chance, a whirlwind chance and the unknown are reluctant to assign an actual tour through the history and philosophy of probability. -

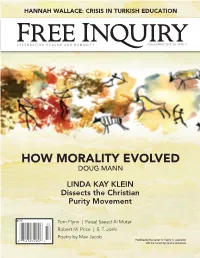

How Morality Evolved Doug Mann

HANNAH WALLACE: CRISIS IN TURKISH EDUCATION CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY February/March 2019 Vol. 39 No. 2 HOW MORALITY EVOLVED DOUG MANN LINDA KAY KLEIN Dissects the Christian Purity Movement F/M 17 $5.95 CDN $5.95 US $5.95 Tom Flynn | Faisal Saeed Al Mutar 03 Robert M. Price | S. T. Joshi Poetry by Max Jacob Published by the Center for Inquiry in association 0 74470 74957 8 with the Council for Secular Humanism For many, mere atheism (the absence of belief in gods and the supernatural) or agnosticism (the view that such questions cannot be answered) aren’t enough. It’s liberating to recognize that supernatural beings are human creations … that there’s no such thing as “spirit” or “transcendence”… that people are undesigned, unintended, and responsible for themselves. But what’s next? Atheism and agnosticism are silent on larger questions of values and meaning. If Meaning in life is not ordained from on high, what small-m meanings can we work out among ourselves? If eternal life is an illusion, how can we make the most of our only lives? As social beings sharing a godless world, how should we coexist? For the questions that remain unanswered after we’ve cleared our minds of gods and souls and spirits, many atheists, agnostics, skeptics, and freethinkers turn to secular humanism. Secular. “Pertaining to the world or things not spiritual or sacred.” Humanism. “Any system of thought or action concerned with the interests or ideals of people … the intellectual and cultural movement … characterized by an emphasis on human interests rather than … religion.” — Webster’s Dictionary Secular humanism is a comprehensive, nonreligious life stance incorporating: A naturalistic philosophy A cosmic outlook rooted in science, and A consequentialist ethical system in which acts are judged not by their conformance to preselected norms but by their consequences for men and women in the world. -

Sex and Justice Author(S): Brian Skyrms Source: the Journal of Philosophy, Vol

Journal of Philosophy, Inc. Sex and Justice Author(s): Brian Skyrms Source: The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 91, No. 6 (Jun., 1994), pp. 305-320 Published by: Journal of Philosophy, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2940983 Accessed: 24/12/2009 18:39 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=jphil. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Philosophy, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Philosophy. http://www.jstor.org SEX AND JUSTICE 305 SEX AND JUSTICE* Some have not hesitated to attributeto men in that state of nature the concept of just and unjust, without bothering to show that they must have had such a concept, or even that it would be useful to them. -

Sexual Selection for Moral Virtues

Name /jlb_qrb822_3060012/820202/Mp_97 03/07/2007 04:48PM Plate # 0 pg 97 # 1 Volume 82, No. 2 THE QUARTERLY REVIEW OF BIOLOGY June 2007 SEXUAL SELECTION FOR MORAL VIRTUES Geoffrey F. Miller Psychology Department, University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131 USA e-mail: [email protected] keywords agreeableness, alternative mating strategies, altruism, assortative mating, behavior genetics, commitment, conscientiousness, costly signaling theory, equilibrium selection, emotion, empathy, ethics, evolutionary psychology, fitness indicators, genetic correlations, good genes, good parents, good partners, human courtship, kin selection, kindness, individual differences, intelligence, mate choice, mental health, moral virtues, mutation load, mutual choice, person perception, personality, reciprocal altruism, sexual fidelity, sexual selection, social cognition, virtue ethics “Human good turns out to be the activity of the soul exhibiting excellence.” Aristotle (350 BC) abstract Moral evolution theories have emphasized kinship, reciprocity, group selection, and equilibrium selection. Yet, moral virtues are also sexually attractive. Darwin suggested that sexual attractiveness may explain many aspects of human morality. This paper updates his argument by integrating recent research on mate choice, person perception, individual differences, costly signaling, and virtue ethics. Many human virtues may have evolved in both sexes through mutual mate choice to advertise good genetic quality, parenting abilities, and/or partner traits. Such virtues may include kindness, fidelity, magnanimity, and heroism, as well as quasi-moral traits like conscientiousness, agreeableness, mental health, and intelligence. This theory leads to many testable predictions about the phenotypic features, genetic bases, and social-cognitive responses to human moral virtues. Introduction tility, and longevity (Langlois et al. 2000; Fink MONG HUMANS, attractive bodies may and Penton-Voak 2002). -

Evolution of Morality Debate on Philosophy Forum, Mar 2004 This Discussion Eventually Wanders Into a Debate on Absolute Certainty

Evolution of Morality Debate on Philosophy Forum, Mar 2004 This discussion eventually wanders into a debate on absolute certainty. All quotations are in red. All responses to quotations by John Donovan unless otherwise noted. Quote: Originally Posted by Mariner I much prefer Dennett's "Darwin's Dangerous Idea" to Dawkins' "The Blind Watchmaker" by the way. Dawkins is too fond of hyperboles, and his arguments are often weak. Unlike Dennett's. I enjoy both authors immensely, though it is true that Dawkins sometimes writes in a somewhat pugalistic and shall we say, exuberant tone. But it makes for entertaining reading, for example have you read this very funny piece? http://www.physics.nyu.edu/faculty/sokal/dawkins.html In any case, both Dawkins and Dennett are clearly philosophical "soulmates". I can't imagine two men more in tune with each others ideas on so many issues. Just look at how Dennett has latched on to Dawkins' "memes" concept and applied it to his theory of consciousness. There is a discussion on this here for those interested in the link between language and the evolution of consciousness: http://forums.philosophyforums.com/...read.php?t=6031 Apologies in advance for the thread promotion. By Probeman (John Donovan) Quote: Originally Posted by jamespetts A characteristic, no doubt, with a strong genetic influence ;-) Seriously, I think there is something to this. Although I would say a strong "memetic" influence, instead. It makes sense to consider the idea that religious beliefs, such as the idea that we are the apple of God's eye, or the chosen people or that the universe was created just for us, etc., are all evolved memes that enhance human (social?) survival. -

When Computer Simulations Lead Us Astray

The Dark Side of the Force: When computer simulations lead us astray and “model think” narrows our imagination — Pre conference draft for the Models and Simulation Conference, Paris, June 12-14 — Eckhart Arnold May 31th 2006 Abstract This paper is intended as a critical examination of the question of when the use of computer simulations is beneficial to scientific expla- nations. This objective is pursued in two steps: First, I try to establish clear criteria that simulations must meet in order to be explanatory. Basically, a simulation has explanatory power only if it includes all causally relevant factors of a given empirical configuration and if the simulation delivers stable results within the measurement inaccuracies of the input parameters. If a simulation is not explanatory, it can still be meaningful for exploratory purposes, but only under very restricted conditions. In the second step, I examine a few examples of Axelrod-style simulations as they have been used to understand the evolution of co- operation (Axelrod, Schußler)¨ and the evolution of the social contract (Skyrms). These simulations do not meet the criteria for explanatory validity and it can be shown, as I believe, that they lead us astray from the scientific problems they have been addressed to solve and at the same time bar our imagination against more conventional but still better approaches. 1 i Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Different aims of computer simulations in science 1 3 Criteria for “explanatory” simulations 2 4 Simulations that fail to explain 7 4.1 Axelrod style simulations of the “evolution of cooperation” . 8 4.1.1 Typical features of Axelrod style simulations .