Electoral Reform and Trade-Offs in Representation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

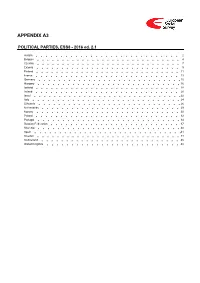

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Challenger Party List

Appendix List of Challenger Parties Operationalization of Challenger Parties A party is considered a challenger party if in any given year it has not been a member of a central government after 1930. A party is considered a dominant party if in any given year it has been part of a central government after 1930. Only parties with ministers in cabinet are considered to be members of a central government. A party ceases to be a challenger party once it enters central government (in the election immediately preceding entry into office, it is classified as a challenger party). Participation in a national war/crisis cabinets and national unity governments (e.g., Communists in France’s provisional government) does not in itself qualify a party as a dominant party. A dominant party will continue to be considered a dominant party after merging with a challenger party, but a party will be considered a challenger party if it splits from a dominant party. Using this definition, the following parties were challenger parties in Western Europe in the period under investigation (1950–2017). The parties that became dominant parties during the period are indicated with an asterisk. Last election in dataset Country Party Party name (as abbreviation challenger party) Austria ALÖ Alternative List Austria 1983 DU The Independents—Lugner’s List 1999 FPÖ Freedom Party of Austria 1983 * Fritz The Citizens’ Forum Austria 2008 Grüne The Greens—The Green Alternative 2017 LiF Liberal Forum 2008 Martin Hans-Peter Martin’s List 2006 Nein No—Citizens’ Initiative against -

A Spectre Haunting - New Dimensions of Youth Protest in Western Europe

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL UMSL Global 1-1-1982 A Spectre Haunting - New Dimensions Of Youth Protest In Western Europe Joyce Marie Mushaben [email protected] Center for International Studies UMSL Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/cis Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mushaben, Joyce Marie and Center for International Studies UMSL, "A Spectre Haunting - New Dimensions Of Youth Protest In Western Europe" (1982). UMSL Global. 11. https://irl.umsl.edu/cis/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in UMSL Global by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Occasional PaJer No. 8208 August, 1982 Occasional Papers The Center for International Studies of the University of Missouri-St. Louis issues Occasional Papers at irre u1ar intervals from ongoing research rejects, thereby providing a viable means for communicating tentative results. Such 11 informal 11 publications reduces mewhat the delay between research and p blica tion, offering an opp.ortunity fo the investigator to obtain reactions wh i 1e st i 11 engaged in the research. ommen ts on these papers, therefore, a.re art i c ul a rl y welcome~ Occasional Pae s sh·o1,1ld not be reproduced or quoted at 1 ngth withou~ the consent of the autho or of the Center for International Stu 1es. A SPECTRE HAUNTING: . NEW DIMENSIONS OF YOUTH PRO EST IN WESTERN EUROPE JOYCE MARIE MUSHABEN ~- -~L! _- ;. :·~ - -~~ . , . '" A SPECTRE HAUNTING: NEW DIMENSIONS OF YOUTH PROTEST IN WESTERN EUROPE Joyce Marie Mushaben · University of Missouri-St. -

Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 5: Macro Report Version: September 14, 2016

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 1 Module 5: Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 5: Macro Report Version: September 14, 2016 Country: Switzerland Date of Election: 20 October 2019 Prepared by: Lukas Lauener, Laurent Bernhard, Anke Tresch Date of Preparation: 16 July 2020 NOTES TO COLLABORATORS There are eight sections (numbered A-H inclusive) in this report. Please ensure that you complete all the sections. The information provided in this report contributes to the macro data portion of the CSES, an important component of the CSES project. The information may be filled out by yourself, or by an expert or experts of your choice. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated. Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g.: electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports, district data) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Answers should be as of the date of the election being studied. Where brackets [ ] appear, collaborators should answer by placing an “X” within the appropriate bracket or brackets. For example: [X] If more space is needed to answer any question, please lengthen the document as necessary. Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 2 Module 5: Macro Report A) DATA PERTINENT TO ELECTION AT WHICH MODULE WAS ADMINISTERED 1a. Type of Election: [X] Parliamentary/Legislative [ ] Parliamentary/Legislative and Presidential [ ] Presidential [ ] Other; please specify: __________ 1b. If the type of election in Question 1a included Parliamentary/Legislative, was the election for the Upper House, Lower House, or both? [ ] Upper House [ ] Lower House [X] Both [ ] Other; please specify: __________ 2a. -

Sectional Analyses of Anti-Political-Establishment Parties

CHALLENGING THE ESTABLISHMENT: CROSS-TEMPORAL AND CROSS- SECTIONAL ANALYSES OF ANTI-POLITICAL-ESTABLISHMENT PARTIES by AMIR-HASSAN ABEDI-DJOURABTCHI M.A., The University of British Columbia, 1995 M.A., Universitat Hannover, Germany, 1992 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Political Science) We accept this thesis as conforming to-the required standard TJ^UNIVERSITY OF BRIT^H COLUMBIA December 2001 © Amir-Hassan Abedi-Djourabtchi, 2001 UBC Special Collections - Thesis Authorisation Form Page 1 of 1 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that' the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of POLITICAL ZciEvci The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date — -r http://www.library.ubc.ca/spcoll/thesauth.html 10/15/2001 ABSTRACT Most studies that have examined parties that challenge the political establishment have focused their attention on certain types of 'anti-political-establishment parties' (a-p- e parties), such as left-libertarian parties or right-wing populist parties. It is argued here that before moving on to an exploration of the reasons behind the electoral success or failure of specific a-p-e parties, one should take a closer look at the preconditions for the success of a-p-e parties in general. -

How Social Movements Matter

HOW SOCIA I MOVEMENT S MATTE R Social Movements, Protest, and Contention Series Editor: Bert Klandermans, Free University, Amsterdam Associate Editors: Sidney Tarrow, Cornell University Vena A. Taylor, The Ohio State University Ron Aminzade, University of Minnesota Volume 10 Marco Giugni, Doug McAdam, and Charles Tilly, eds., How Social Movements Matter Volume 9 Cynthia L. Irvin, Militant Nationalism: Between Movement and Party in Ireland and the Basque Country Volume 8 Raka Ray Fields of Protest: Women's Movements in India Volume 7 Michael P Hanagan, Leslie Page Moch, and Wayne te Brake, eds., Challenging Authority: The Historical Study of Contentious Politics Volume 6 Donatella della Porta and Herbert Reiter, eds., Policing Protest: The Control of Mass Demonstrations in Western Democracies Volume 5 Hanspeter Kriesi, Ruud Koopmans, Jan Willem Duyvendak, and Marco G. Giugni, New Social Movements in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis Volume 4 Hank Johnston and Bert Klandermans, eds., Social Movements and Culture Volume 3 J. Craig Jenkins and Bert Klandermans, eds., The Politics of Social Protest: Comparative Perspectives on States and Social Movements Volume 2 John Foran, ed., A Century of Revolution: Social Movements in Iran Volume 1 Andrew Szasz, EcoPopulism: Toxic Waste and the Movement for Environmental Justice HOW SOCIAL MOVEMENTS MATTER Marco Giugni, Doug McAdam, and Charles Tilly, editors Foreword b y Sidne y Tarro w Social Movements, Protest, and Contention Volume 10 University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis • London Copyright 1999 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

The Party System in Switzerland: an International Comparison a Study Based on Data from 1971-1999 National Council Elections

The Party System in Switzerland: an international comparison A study based on data from 1971-1999 National Council elections ,.( Office fédéral de la statistique Bundesamt für Statistik Ufficio federale di statistica 111 Swiss Federal Statistical Office Neuchâtel, 2003 OFS BFS SFSO The «Swiss Statistics» series published by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (SFSO) covers the following fields: 0 Basic statistical data and overviews 11 Transport and communications l Population 12 Money, banks, insurance companies 2 Territory and environment 13 Social security 3 Employment and incarne from employment 14 Health 4 National economy 15 Education and science 5 Prices 16 Culture, media, time use 6 lndustry and services 17 Politics 7 Agriculture and forestry 18 Public administration and fin ance 8 Energy 19 Law and justice 9 Construction and housing 20 Incarne and standard of living of the population 10 Tourism 21 Sustainable development and regional disparities 8.2003 500 100495 Swiss Statistics he a System in S itzerland: an international comparison A study based on data from 1971-1999 National Council elections Klaus Armingeon Professor of Political Science University of Berne Office fédéral de la statistique Bundesamt für Statistik Ufficio federale di statistica Il1 Swiss Federal Statistical Office Neuchâtel, 2003 OFS BFS SFSO Published by: Swiss Federal Statistical Office (SFSO) Information: Werner Seitz, Madeleine Schneider, SFSO, 'Phone 032 713 65 85 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Author. Klaus Armingeon -

Shirking and Slacking in Parliament∗

Shirking and Slacking in Parliament∗ Elena Frech† Niels D. Goet‡ Universit´ede Gen`eve University of Oxford Simon Hug§ Universit´ede Gen`eve Paper prepared for presentation at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (Boston, August, 2018) August 15, 2018 Abstract How and why do the activities of members of parliament (MPs) change in response to electoral constraints? While MPs can usually select from a wide arsenal of parliamentary tactics (i.e. speak, vote, etc.), their activi- ties are circumscribed by countless factors. These limitations may include, among others, constituency interests, parliamentary rules, and the “party ∗Earlier versions of this paper were presented in a research seminar at the University of Fribourg at the Annual Meeting of the Swiss Political Science Association (Geneva, February 5-6, 2018), at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association (Chicago, April 5-8, 2018) and at the General Conference of the European Political Science Association (Vienna, June, 2018). Helpful comments by the participants at these events, especially by the discussants Stefanie Bailer, Jorge M. Fernandes, Harry Grundy, and Connor Little as well as partial financial support by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grants No. 100012-111909, 100012-129737 and 100017L-162427) is gratefully acknowledged. We would also like to thank Thomas D¨ahler and Peter Frankenbach, respectively Christian M¨ullerfor providing data on the parliament in Basel-Stadt, respectively Basel-Land. We further acknowledge -

Politics After Financial Crises, 1870-2014

Freie Universit¨atBerlin Graduate School of North American Studies Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors/einer Doktorin der Wirtschaftswissenschaft des Fachbereichs Wirtschaftswissenschaft der Freien Universit¨atBerlin Financial Crises: Political and Social Implications vorgelegt von Manuel Funke, M.A. aus M¨unster Berlin, November 2016 Erstgutachter: Prof. Irwin Collier, Ph.D. Freie Universit¨atBerlin John-F.-Kennedy-Institut Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Moritz Schularick Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universit¨atBonn Institut f¨urMakro¨okonomik und Okonometrie¨ Tag der Disputation: 25. Juli 2017 Koautorenschaften und Publikationen Das zweite Kapitel dieser Dissertation (“Going to extremes: Politics after financial crises, 1870-2014”) wurde zusammen mit Prof. Dr. Moritz Schularick von der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universit¨at Bonn und Prof. Dr. Christoph Trebesch von der Ludwig-Maximilians- Universit¨atM¨unchen verfasst. Dieses Kapitel wurde zudem im Jahre 2015 zweimal in Form eines Working Papers und im Jahre 2016 schlussendlich als Journal-Artikel ver¨offentlicht. Die offiziellen Literaturangaben zu diesen insgesamt drei Publikationen lauten wie folgt: • Manuel Funke, Moritz Schularick, Christoph Trebesch. 2015. Going to Extremes: Politics after Financial Crises, 1870-2014. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 10884. • Manuel Funke, Moritz Schularick, Christoph Trebesch. 2015. Going to Extremes: Politics after Financial Crises, 1870-2014. CESifo Working Paper No. 5553. • Funke, Manuel, Moritz Schularick, Christoph Trebesch. 2016. Going to extremes: Politics after financial crises, 1870-2014. European Economic Review 88: 227-260. Es sei erw¨ahnt, dass Kapitel Nr. 2 im Wesentlichen der im Journal European Economic Review ver¨offentlichten Version aus dem Jahre 2016 entspricht, wobei geringf¨ugigekontextabh¨angige Anderungen¨ vor- behalten sind. Die ¨ubrigenKapitel dieser Arbeit (Nr. -

Codebook Polidoc COHESIFY REPCONG

Polidoc.net CODEBOOK National and Regional Manifestos and other Political Documents Collected for the Research Projects ”Representation in Europe: Congruence between Preferences of Elites and Voters” (REPCONG) and ”The Impact of EU Cohesion Policy on European Identification” (COHESIFY) Prepared by the Polidoc.net Team headed by Thomas Br¨auninger (University of Mannheim), Marc Debus (University of Mannheim), Kenneth Benoit (London School of Economics and Political Science) and Julian Bernauer (Mannheim Centre for European Social Research) November 21, 2017 1 1 polidoc.net- The Political Documents Archive The Political Documents Archive contains election manifestos, coalition agreements, gov- ernment declarations and various other documents of political actors from developed democracies. Currently, the archive builds on a stock of more than 3000 political doc- uments from 20 European countries. The aim of the repository is to provide political texts in order to facilitate scholarly research in different areas of comparative politics such as party competition, coalition politics, legislative decision-making or electoral be- havior. National electoral manifestos have been collected in the course of the REPCONG project, and the archive includes party manifestos for regional elections in several Euro- pean democracies. Because the process of European integration resulted in a strength- ening of regions in EU member states and in countries that want to join the European Union, the relevance of the regional level for political decision-making has increased dur- ing the last decades. Therefore, also the policy profiles of regional parties are required to get a full picture of democratic responsiveness in European states across all levels of the political system. -

Online Appendix

Appendix A: Excluded cabinets1 . Austria: Breisky (1922, acting); Bierlein (2019, ad interim). Belgium: Delacroix (1919, national unity); Carton de Wiart (1920, national unity), Jaspar (1926, national unity); van Zeeland (1935/1936, national unity); Jason (1937, national unity); Spaak (1938, national unity); Pierlot (1939/1944, national unity); Pierlot (1940, in exile); van Acker (1945, national unity); Wilmès (2019, caretaker). Bulgaria: Berov (1992, technocratic); Indzhova (1994, caretaker); Sofianski (1997, caretaker); Raykov (2013, caretaker); Oresharski (2013, technocratic); Bliznashki (2014, caretaker); Gerdzhikov (2017, caretaker). Cyprus: Vassiliou (1988, non-partisan). Czechoslovakia: Černý (1920 and 1926, caretaker); Sirový (1938, caretaker). Czechia: Tošovský (1998, caretaker); Topolanek (2006, unsuccessful); Fischer (2009, caretaker); Rusnok (2014, unsuccessful); Babiš (2017, unsuccessful). Denmark: Zahle (1916, national unity); Liebe (1920, caretaker); Friis (1920, caretaker); Stauning (1940, national unity); Buhl (1942, national unity); Scavenius, (1942/1943, national unity); Buhl (1945, national unity). Estonia: Jaakson (1924, national unity); Pats (1933/1934, non-partisan/acting); Tarand (1994, caretaker). Finland: Cajander (1922/1924, caretaker); Tuomioja (1953, caretaker); von Fieandt (1957, caretaker); Kuuskoski (1958, caretaker); Lehto (1963, caretaker); Aura (1970/1971, caretaker); Liinamaa (1975, caretaker). France: Hautpoul (1849, presidential); “Small/Last Ministry” (1851, technocratic); de Broglie (1877, presidential);