Federico's Prison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ERNANI Web.Pdf

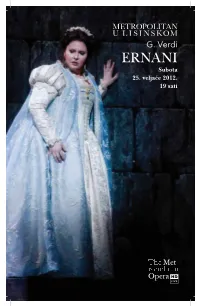

Foto: Metropolitan opera G. Verdi ERNANI Subota, 25. veljae 2012., 19 sati THE MET: LIVE IN HD SERIES IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A GENEROUS GRANT FROM ITS FOUNDING SPONZOR Neubauer Family Foundation GLOBAL CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP OF THE MET LIVE IN HD IS PROVIDED BY THE HD BRODCASTS ARE SUPPORTED BY Giuseppe Verdi ERNANI Opera u etiri ina Libreto: Francesco Maria Piave prema drami Hernani Victora Hugoa SUBOTA, 25. VELJAČE 2012. POČETAK U 19 SATI. Praizvedba: Teatro La Fenice u Veneciji, 9. ožujka 1844. Prva hrvatska izvedba: Narodno zemaljsko kazalište, Zagreb, 18. studenoga 1871. Prva izvedba u Metropolitanu: 28. siječnja 1903. Premijera ove izvedbe: 18. studenoga 1983. ERNANI Marcello Giordani JAGO Jeremy Galyon DON CARLO, BUDUĆI CARLO V. Zbor i orkestar Metropolitana Dmitrij Hvorostovsky ZBOROVOĐA Donald Palumbo DON RUY GOMEZ DE SILVA DIRIGENT Marco Armiliato Ferruccio Furlanetto REDATELJ I SCENOGRAF ELVIRA Angela Meade Pier Luigi Samaritani GIOVANNA Mary Ann McCormick KOSTIMOGRAF Peter J. Hall DON RICCARDO OBLIKOVATELJ RASVJETE Gil Wechsler Adam Laurence Herskowitz SCENSKA POSTAVA Peter McClintock Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: Radnja se događa u Španjolskoj 1519. godine. Stanka nakon prvoga i drugoga čina. Svršetak oko 22 sata i 50 minuta. Tekst: talijanski. Titlovi: engleski. Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: PRVI IN - IL BANDITO (“Mercè, diletti amici… Come rugiada al ODMETNIK cespite… Oh tu che l’ alma adora”). Otac Don Carlosa, u operi Don Carla, Druga slika dogaa se u Elvirinim odajama u budueg Carla V., Filip Lijepi, dao je Silvinu dvorcu. Užasnuta moguim brakom smaknuti vojvodu od Segovije, oduzevši sa Silvom, Elvira eka voljenog Ernanija da mu imovinu i prognavši obitelj. -

Checklist of Post-1500 Italian Manuscripts in the Newberry Library Compiled by Cynthia S

Checklist of Post-1500 Italian Manuscripts in the Newberry Library compiled by Cynthia S. Wall - 1991 The following inventory lists alphabetically by main entry the post-1500 Italian manuscripts in the Newberry Library. (Pre-1500 or “medieval” manuscripts are inventoried by de Ricci.) The parameters for this inventory are quite wide: included are (hopefully) all manuscripts in the Case and Wing collections which are either by an Italian author, located in Italy, written in Italian, and/or concerning Italian affairs. For example, the reader will find not only numerous papal documents, a letter by Michel Angelo Buonarroti, and the papers of the Parravicini family, but also a German transcription of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor and a nineteenth-century political analysis of Sicily by the English consul John Goodwin. This list was compiled from the shelf lists of Case (including Cutter, lower case, fixed location, and Library of Congress call numbers) and Wing (including Case Wing, Cutter, and Library of Congress). Many of these entries are abbreviated, and the reader may find additional bibliographic information in the main card catalog. This inventory does not include the Library’s collection of facsimiles of various Italian manuscripts in other libraries. Entires for such facsimiles will be found in the online catalog. C. S. Wall July 1991 Agrippa von Nettesheim, Heinrich Cornelius, 1486?-1535. Cabala angelica d’Enrico Cornelio Agrippa [manuscript] [17–]. Case MS 5169 ALBERGHI, Paolo. Littanie popolari a 3 voci … [n.p., 17–] Case folio MS oM 2099 .L5 A42 ALBINONI, Tomaso, 1671-1750. [Trio-sonata, violins & continuo, op.1, no.2, F major] Sonata for two violons & base [sic] in F maj. -

Donizetti Operas and Revisions

GAETANO DONIZETTI LIST OF OPERAS AND REVISIONS • Il Pigmalione (1816), libretto adapted from A. S. Sografi First performed: Believed not to have been performed until October 13, 1960 at Teatro Donizetti, Bergamo. • L'ira d'Achille (1817), scenes from a libretto, possibly by Romani, originally done for an opera by Nicolini. First performed: Possibly at Bologna where he was studying. First modern performance in Bergamo, 1998. • Enrico di Borgogna (1818), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: November 14, 1818 at Teatro San Luca, Venice. • Una follia (1818), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: December 15, 1818 at Teatro San Luca,Venice. • Le nozze in villa (1819), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: During Carnival 1820-21 at Teatro Vecchio, Mantua. • Il falegname di Livonia (also known as Pietro, il grande, tsar delle Russie) (1819), libretto by Gherardo Bevilacqua-Aldobrandini First performed: December 26, 1819 at the Teatro San Samuele, Venice. • Zoraida di Granata (1822), libretto by Bartolomeo Merelli First performed: January 28, 1822 at the Teatro Argentina, Rome. • La zingara (1822), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: May 12, 1822 at the Teatro Nuovo, Naples. • La lettera anonima (1822), libretto by Giulio Genoino First performed: June 29, 1822 at the Teatro del Fondo, Naples. • Chiara e Serafina (also known as I pirati) (1822), libretto by Felice Romani First performed: October 26, 1822 at La Scala, Milan. • Alfredo il grande (1823), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: July 2, 1823 at the Teatro San Carlo, Naples. • Il fortunate inganno (1823), libretto by Andrea Tottola First performed: September 3, 1823 at the Teatro Nuovo, Naples. -

Pacini, Parody and Il Pirata Alexander Weatherson

“Nell’orror di mie sciagure” Pacini, parody and Il pirata Alexander Weatherson Rivalry takes many often-disconcerting forms. In the closed and highly competitive world of the cartellone it could be bitter, occasionally desperate. Only in the hands of an inveterate tease could it be amusing. Or tragi-comic, which might in fact be a better description. That there was a huge gulf socially between Vincenzo Bellini and Giovanni Pacini is not in any doubt, the latter - in the wake of his highly publicised liaison with Pauline Bonaparte, sister of Napoleon - enjoyed the kind of notoriety that nowadays would earn him the constant attention of the media, he was a high-profile figure and positively reveled in this status. Musically too there was a gulf. On the stage since his sixteenth year he was also an exceptionally experienced composer who had enjoyed collaboration with, and the confidence of, Rossini. No further professional accolade would have been necessary during the early decades of the nineteenth century On 20 November 1826 - his account in his memoirs Le mie memorie artistiche1 is typically convoluted - Giovanni Pacini was escorted around the Conservatorio di S. Pietro a Majella of Naples by Niccolò Zingarelli the day after the resounding success of his Niobe, itself on the anniversary of the prima of his even more triumphant L’ultimo giorno di Pompei, both at the Real Teatro S.Carlo. In the Refettorio degli alunni he encountered Bellini for what seems to have been the first time2 among a crowd of other students who threw bottles and plates in the air in his honour.3 That the meeting between the concittadini did not go well, this enthusiasm notwithstanding, can be taken for granted. -

Messa Per Rossini

Messa per Rossini L'oeuvre oubliée... 13 novembre 2018 30 ans Un événement exceptionnel pour fêter les 30 ans du chœur ! 1792 – 1868 Pour le 150è anniversaire de la disparition du maître, le chœur Arianna présente pour la première fois dans notre région une œuvre du Répertoire Romantique majeure et pourtant oubliée : Messa per Rossini composée en 1868-69 par Antonio Antonio Carlo Antonio Federico Alessandro BUZZOLA BAZZINI PEDROTTI CAGNONI RICCI NINI Requiem – Kyrie Dies irae Tuba mirum Quid sum miser Recordare Jesu Ingemisco Raimondo Carlo Gaetano Pietro Lauro Teodulo Giuseppe BOUCHERON COCCIA GASPARI PLATANIA ROSSI MABELLINI VERDI Confutatis – Oro supplex Lacrymosa Domine Jesu Sanctus Agnus Dei Lux æterna Libera me 13 novembre 1868, l'Europe musicale est sous le choc : Rossini est mort ! Les hommages pleuvent de toutes parts : compositeurs, musiciens, politiciens ou simples mélomanes, aucun ne trouve assez de mots pour exprimer son désarroi face à cette perte immense. Il est vrai que, de son vivant même, Gioacchino Rossini est devenu une légende, lui qui, après avoir composé des chefs-d'œuvres immortels, dont plus de trente opéras, a décidé, dès 1830, de se retirer en n'écrivant plus que pour ses amis. Cette longue « retraite » voit naître tout de même des œuvres extrêmement célèbres telles que le Stabat Mater (1841) ou la Petite Messe Solennelle (1864). L'Italie est en deuil Verdi souhaite un hommage au maître digne de son talent, de son génie. Non pas un simple concert hommage ou des discours... Il faut une œuvre monumentale qui rappelle au monde, aux générations futures, à quel point Rossini était immense. -

The Romantic Trumpet Part Two

110 HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL THE ROMANTIC TRUMPET PART TWO Edward H. Tarr Continued from Historic Brass Society Journal, volume 5 (1993), pages 213-61. The two-part series is an expansion of an article written for Performance Practice Encyclopedia. We thank Roland Jackson, editor of this forthcoming reference work, for permission to we this material in HBSJ. For a Conclusion to Part One, containinga list oferrata, please see followingthe endnotes for the current installment. Summary of Part One In Part One, the author first attempted to show the various types of trumpets, cornets, and flugelhorns, both natural and chromaticized, that existed before the advent of valves, together with their literature. Before there were valved trumpets, for example, natural trumpets, etc., were made chromatic by the technique of hand-stopping or by being fitted with slides or keys. He then showed how the first valved brass instruments—in particular trumpets, and to a lesser extent, comets—were accepted into musical circles. Introduction to Part Two In Part Two, it is the author's aim to raise the flag on a forgotten figure in brass history— one who was reponsible not only for the development ofboth the Vienna valve and the rotary valve, but also for the creation of the first solo compositions for the newly invented valved trumpet: Josef Kail (1795-1871), the first professor of valved trumpet at the Prague Conservatory (served 1826-1867). For this reason, the central part of this study will be devoted to works hitherto unknown, written for the trumpet (and to a lesser extent the cornet, flugelhom, horn, and trombone) during his time. -

N15-16-17 Lettera Orvietana

Quadrimestrale d’informazione culturale dell’Istituto Storico Artistico Orvietano Lettera Orvietana Anno IX N. 24 dicembre 2008 L’Istituto accoglie l’Archivio del Movimento Federalista Europeo l Movimento Federalista Europeo è presente in città dal 1990. IMolte ed impegnative le iniziative della Sezione di Orvieto, in particolar modo nei primi anni di attività. Convegni ed incontri, valide collaborazioni con l’allora Azienda di promozione turistica dell’Orvietano, in un clima di ardente europeismo. In seguito, la politica gestionale, per questioni organizzative e manifeste diffi- coltà nell’individuazione di sinergie nelle contribuzioni, è stata caratterizzata da una forma di attivismo meno visibile, quasi som- merso, ma non meno efficace e fervente. In tal senso, il rapporto con l’Istituto Storico Artistico Orvietano appare tra i più consi- stenti. Tanto che l’Archivio della Sezione di Orvieto del Movi- mento Federalista Europeo è adesso conservato presso la sede del- l’Isao, con documenti, materiali propagandistici e pubblicazioni di settore in corso di catalogazione. Umberto Prencipe, La chiesa di San Giovenale a Orvieto, 1904, Orvieto, Fondazione CRO. (G.C.) Il nuovo anno porterà… Sommario I 60 anni della Costituzione 3 on sappiamo, come è ovvio, che cosa riserverà il nuovo anno al nostro sodalizio culturale. Sono molto Ndifficili le previsioni, anche a media scadenza, si capisce. In periodi storici piuttosto stagnanti, le cer- tezze divengono purtroppo auspici e, malgrado le buone volontà, bisogna muoversi con estrema cautela, per -

ARSC Journal

THE MARKETPLACE HOW WELL DID EDISON RECORDS SELL? During the latter part of 1919 Thomas A. Edison, Inc. began to keep cumulative sales figures for those records that were still available. The documents were continued into 1920 and then stopped. While the documents included sales figures for all series of discs time allowed me to copy only those figures for the higher priced classical series. Thus the present article includes the 82,000 ($2.00); 82,500 ($2.50); 83,000 ($3.00) and 84,000 ($4.00) series. Should there be sufficient interest it may be possible to do the other series at a later date. While the document did list some of the special Tone-Test records pressing figures were included for only two of them. I have arbitrarily excluded them and propose to discuss the Edison Tone Tests at a later date. The documents also originally included supplementary listings, which, for the sake of convenience, have been merged into the regular listings. The type copy of the major portion of the listings has been taken from regular Edison numerical catalogs and forms the framework of my forthcoming Complete Edison Disc Numerical Catalog. Several things may be noted: 1) Many of the sales figures seem surprisingly small and many of the records must be classed as rarities; 2) Deletion was not always because of poor sales-mold damage also played a part; 3) Records were retained even with extremely disappointing sales. Without a knowledge of the reason for discontinuance we cannot assume anything concerning records that had already been discontinued. -

Nini, Bloodshed, and La Marescialla D'ancre

28 Nini, bloodshed, and La marescialla d’Ancre Alexander Weatherson (This article originally appeared in Donizetti Society Newsletter 88 (February 2003)) An odd advocate of so much operatic blood and tears, the mild Alessandro Nini was born in the calm of Fano on 1 November 1805, an extraordinary centre section of his musical life was to be given to the stage, the rest of it to the church. It would not be too disrespectful to describe his life as a kind of sandwich - between two pastoral layers was a filling consisting of some of the most bloodthirsty operas ever conceived. Maybe the excesses of one encouraged the seclusion of the other? He began his strange career with diffidence - drawn to religion his first steps were tentative, devoted attendance on the local priest then, fascinated by religious music - study with a local maestro, then belated admission to the Liceo Musicale di Bologna (1827) while holding appointments as Maestro di Cappella at churches in Montenovo and Ancona; this stint capped,somewhat surprisingly - between 1830 and 1837 - by a spell in St. Petersburg teaching singing. Only on his return to Italy in his early thirties did he begin composing in earnest. Was it Russia that introduced him to violence? His first operatic project - a student affair - had been innocuous enough, Clato, written at Bologna with an milk-and-water plot based on Ossian (some fragments remain), all the rest of his operas appeared between 1837 and 1847, with one exception. The list is as follows: Ida della Torre (poem by Beltrame) Venice 1837; La marescialla d’Ancre (Prati) Padua 1839; Christina di Svezia (Cammarano/Sacchero) Genova 1840; Margarita di Yorck [sic] (Sacchero) Venice 1841; Odalisa (Sacchero) Milano 1842; Virginia (Bancalari) Genova 1843, and Il corsaro (Sacchero) Torino 1847. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

Maria Di Rohan

GAETANO DONIZETTI MARIA DI ROHAN Melodramma tragico in tre atti Prima rappresentazione: Vienna, Teatro di Porta Carinzia, 5 VI 1843 Donizetti aveva già abbozzato l'opera (inizialmente intitolata Un duello sotto Richelieu) a grandi linee a Parigi, nel dicembre 1842, mentre portava a termine Don Pasquale; da una lettera del musicista si desume che la composizione fu ultimata il 13 febbraio dell'anno successivo. Donizetti attraversava un periodo di intensa attività compositiva, forse consapevole dell'inesorabile aggravarsi delle proprie condizioni di salute; la "prima" ebbe luogo sotto la sua direzione e registrò un convincente successo (furono apprezzate soprattutto l'ouverture ed il terzetto finale). L'opera convinse essenzialmente per le sue qualità drammatiche, eloquentemente rilevate dagli interpreti principali: Eugenia Tadolini (Maria), Carlo Guasco (Riccardo) e Giorgio Ronconi (Enrico); quest'ultimo venne apprezzato in modo particolare, soprattutto nel finale. Per il Theatre Italien Donizetti preparò una nuova versione, arricchita di due nuove arie, nella quale la parte di Armando fu portata dal registro di tenore a quello di contralto (il ruolo fu poi interpretato en travesti da Marietta Brambilla). Con la rappresentazione di Parma (primo maggio 1844) Maria di Rohan approdò in Italia dove, da allora, è stata oggetto soltanto di sporadica considerazione. Nel nostro secolo è stata riallestita a Bergamo nel 1957 ed alla Scala nel 1969, oltre all'estero (a Londra e a New York, dove è apparsa in forma di concerto). Maria di Rohan segna forse il punto più alto di maturazione nell'itinerario poetico di Donizetti; con quest'opera il musicista approfondì la propria visione drammatica, a scapito di quella puramente lirica e belcantistica, facendo delle arie di sortita un vero e proprio studio di carattere e privilegiando i duetti ed i pezzi d'assieme in luogo degli 276 episodi solistici (ricordiamo, tra i momenti di maggior rilievo, l'aria di Maria "Cupa, fatal mestizia" ed il duetto con Chevreuse "So per prova il tuo bel core"). -

MODELING HEROINES from GIACAMO PUCCINI's OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

MODELING HEROINES FROM GIACAMO PUCCINI’S OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Naomi A. André, Co-Chair Associate Professor Jason Duane Geary, Co-Chair Associate Professor Mark Allan Clague Assistant Professor Victor Román Mendoza © Shinobu Yoshida All rights reserved 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................iii LIST OF APPENDECES................................................................................................... iv I. CHAPTER ONE........................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION: PUCCINI, MUSICOLOGY, AND FEMINIST THEORY II. CHAPTER TWO....................................................................................................... 34 MIMÌ AS THE SENTIMENTAL HEROINE III. CHAPTER THREE ................................................................................................. 70 TURANDOT AS FEMME FATALE IV. CHAPTER FOUR ................................................................................................. 112 MINNIE AS NEW WOMAN V. CHAPTER FIVE..................................................................................................... 157 CONCLUSION APPENDICES………………………………………………………………………….162 BIBLIOGRAPHY..........................................................................................................