Nasarawa State, Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESS RELEASE June 25, 2021 for Immediate Release U.S. Embassy

United States Diplomatic Mission to Nigeria, Public Affairs Section Plot 1075, Diplomatic Drive, Central Business District, Abuja Telephone: 09-461-4000. Website at http://nigeria.usembassy.gov PRESS RELEASE June 25, 2021 For Immediate Release U.S. Embassy Abuja Partners Channels Academy to Train Conflict Reporters The U.S. Embassy Abuja, in partnership with Channels Academy, has trained over 150 journalists on Conflict Reporting and Peace Journalism. In her opening remarks, the U.S. Embassy Spokesperson/Press Attaché Jeanne Clark noted that the United States recognized that security challenges exist in many forms throughout the country, and that journalists are confronted with responsibility to prioritize physical safety in addition to meeting standards of objectivity and integrity in conflict. She urged the journalists to share their experiences throughout the course of the three-day seminar and encouraged participants to identify new ways to address these security challenges. The trainer Professor Steven Youngblood from the U.S. Center for Global Peace Journalism – Park University defined and presented principles for peace journalism in conflict reporting. He cautioned journalists to refrain from what he termed war journalism. He said, "war journalism is a pattern of media coverage that includes overvaluing violent, reactive responses to conflict while undervaluing non-violent, developmental responses.” The Provost of Channels Academy, Mr Kingsley Uranta, showed appreciation for the continuous partnership with the U.S. Embassy and for bringing such training opportunities to Nigerian journalists. He also called on conflict reporters to be peace ambassadors. The training took place virtually via Zoom on June 22 – 24, 2021. Journalists converged in American Spaces in Abuja, Kano, Bauchi Sokoto, Maiduguri, Awka, and Ibadan. -

Fine Particulate Distribution and Assessment in Nasarawa State – Nigeria

IOSR Journal of Applied Physics (IOSR-JAP) e-ISSN: 2278-4861.Volume 8, Issue 2 Ver. I (Mar. - Apr. 2016), PP 32-38 www.iosrjournals Fine Particulate Distribution and Assessment in Nasarawa State – Nigeria J.U. Ugwuanyi1, A.A. Tyovenda2, T.J. Ayua3 1,2,3 Department Of Physics, University Of Agriculture Makurdi, Benue State - Nigeria Abstract: The purpose of this work is to analyze fine particulate matter (PM10 ) distribution in the ambient air of some major towns in Nasarawa State-North central Nigeria using a high volume respirable dust sampler (APM 460 NL) model, also the meteorological parameters of the State have been correlated with the measured values. Ambient air laden with suspended particulates enter the APM 460 NL system through the inlet pipe, which separates the air into fine and coarse particles. The PM10 concentrations were analyzed to obtain the monthly average PM10 concentration and monthly maximum concentration. The results show that Nasarawa State towns of Karu and Lafia have fine particulates loading in the ambient air more than the recommended standard set by NAAQS and WHO. Variation trends of pollution levels were also identified. The fine particulate matter PM10 average concentrations in the ambient air of Nasarawa State towns had average values increase in the range of 4.0 – 18.0µg/m3 per month. The level of monthly increase of maximum average concentrations also had readings in the range of 8.0 – 20.0 µg/m3 per month. These values were compared with the NAAQS to obtain the toxicity potential for all the study towns in the State. -

An Uncertain Future: Oil Contracts and Stalled Reform in São Tomé E

São Tomé e Príncipe HUMAN An Uncertain Future RIGHTS Oil Contracts and Stalled Reform in São Tomé e Príncipe WATCH An Uncertain Future Oil Contracts and Stalled Reform in São Tomé e Príncipe Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-675-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org August 2010 1-56432-675-6 An Uncertain Future Oil Contracts and Stalled Reform in São Tomé e Príncipe Map of São Tomé e Príncipe ................................................................................................ 1 Glossary of Acronyms ......................................................................................................... 2 Summary ........................................................................................................................... 3 Background ........................................................................................................................ 7 Oil Sector Development: Licenses for Exploration ............................................................ -

A Study of Awka Metropolis Anambra State, Nigeria

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 7, No. 5; May 2016 Urban Poverty Incidence in Nigeria: A Study of Awka Metropolis Anambra State, Nigeria Mbah, Stella I., Ph.D Department of Business Administration Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University Igbariam, Anambra State Nigeria Mgbemena, Gabriel C. Department of Business Administration Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University Igbariam, Anambra State Nigeria Ejike, Daniel C. Department of Business Administration Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University Igbariam, Anambra State Nigeria Abstract This study examined poverty situation in Awka metropolis of Anambra State, Nigeria, using the P-alpha class of poverty measure. To achieve this objective, a structured questionnaire was administered to 399 heads of households selected from mixed socio-economic backgrounds. The study revealed that 49 percent of the respondents were considered to be poor, with 0.17 poverty gap index and a 0.03 severity of poverty index. However, the indicators were considered to be modest when compared with the national rates. The causes of poverty in Awka metropolis include: lack or inadequate supply of some identified basic necessities of life such as shelter, potable water, and sanitation, basic healthcare services, electricity and educational services. As a result of these inadequacies, there are psychological distress, increase in destitution, child labour, violent crime, and prostitution. It was therefore recommended among others that government should step up public investment in urban infrastructure, provision of credit facilities, involvement of the people in development decision that affects their lives or participatory budgetary process and most especially, good governance at the municipal level with accountability and transparency to stamp out corrupt tendencies which has inhibited past developmental efforts of the government. -

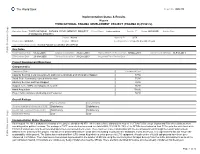

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR4370 Implementation Status & Results Nigeria THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (FADAMA III) (P096572) Operation Name: THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 7 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: (FADAMA III) (P096572) Country: Nigeria Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): National Fadama Coordination Office(NFCO) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Jul-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 07-Nov-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 11-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 23-Mar-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Capacity Building, Local Government, and Communications and Information Support 87.50 Small-Scale Community-owned Infrastructure 75.00 Advisory Services and Input Support 39.50 Support to the ADPs and Adaptive Research 36.50 Asset Acquisition 150.00 Project Administration, Monitoring and Evaluation 58.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview As at August 19, 2011, disbursement status of the project stands at 46.87%. All the states have disbursed to most of the FCAs/FUGs except Jigawa and Edo where disbursement was delayed for political reasons. The savings in FUEF accounts has increased to a total ofN66,133,814.76. 75% of the SFCOs have federated their FCAs up to the state level while FCAs in 8 states have only been federated up to the Local Government levels. -

1Anzaku, IM, 2Ishaya, KI Ishaya, KI & 2Ogah, at Ogah, at Email

Identification and Characteristics of Gully Erosion in North Central Nigeria: Case Study of Nasarawa State IDENTIFICATION AND CHARACTERISTICS OF GULLY EROSION IN NORTH CENTRAL NIGERIA: CASE STUDY OF NASARAWA STATE 111Anzaku, I. M., 222Ishaya, K. I. &&& 222Ogah, A. T. 111Department of Science, Bayero University, Kano, Kano State, Nigeria Department of Geography, Nasarawa State University, KeffiKeffi,, Nigeria EmailEmail:: [email protected] ABSTRACTABSTRACT:: This study assessed morphometric of gullies in Nasarawa state, Nigeria with a view to ascertain the level of distinction of the phenomenon in the state. Landscape morphology and the process that bring them into being have always been of interest to scholars. Landform evolution is therefore a product of the balancing of these forces in the presence of climatic and endogenic change geomorphic interaction is provided by the sun, geothermal and gravitational energy.Both primary and secondary data source were employed for this study. The primary data were collected from direct field observation and measurements. Secondary data were gathered through the review of relevant literature. A recommendation survey to ascertain the general characteristics of gullies in the state was carried out with the aid of topography map of the study area.The results generated from the field were subjected to statistical and laboratory analysis. The results of the findings revealed that gullies in Lafia and Wamba LGA of Nasarawa state are more affected 80% Kilema gully site in Lafia LGA recorded the highest intern of gully length 315m followed by Traffic in Wamba LGA 303m, UngwaSharu in Lafia LGA recorded the highest figure in term of gully length 325m followed by Traffic in Wamba LGA 285m respectively. -

Surviving Works: Context in Verre Arts Part One, Chapter One: the Verre

Surviving Works: context in Verre arts Part One, Chapter One: The Verre Tim Chappel, Richard Fardon and Klaus Piepel Special Issue Vestiges: Traces of Record Vol 7 (1) (2021) ISSN: 2058-1963 http://www.vestiges-journal.info Preface and Acknowledgements (HTML | PDF) PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre (HTML | PDF) Chapter 2 Documenting the early colonial assemblage – 1900s to 1910s (HTML | PDF) Chapter 3 Documenting the early post-colonial assemblage – 1960s to 1970s (HTML | PDF) Interleaf ‘Brass Work of Adamawa’: a display cabinet in the Jos Museum – 1967 (HTML | PDF) PART TWO ARTS Chapter 4 Brass skeuomorphs: thinking about originals and copies (HTML | PDF) Chapter 5 Towards a catalogue raisonnée 5.1 Percussion (HTML | PDF) 5.2 Personal Ornaments (HTML | PDF) 5.3 Initiation helmets and crooks (HTML | PDF) 5.4 Hoes and daggers (HTML | PDF) 5.5 Prestige skeuomorphs (HTML | PDF) 5.6 Anthropomorphic figures (HTML | PDF) Chapter 6 Conclusion: late works ̶ Verre brasscasting in context (HTML | PDF) APPENDICES Appendix 1 The Verre collection in the Jos and Lagos Museums in Nigeria (HTML | PDF) Appendix 2 Chappel’s Verre vendors (HTML | PDF) Appendix 3 A glossary of Verre terms for objects, their uses and descriptions (HTML | PDF) Appendix 4 Leo Frobenius’s unpublished Verre ethnological notes and part inventory (HTML | PDF) Bibliography (HTML | PDF) This work is copyright to the authors released under a Creative Commons attribution license. PART ONE CONTEXT Chapter 1 The Verre Predominantly living in the Benue Valley of eastern middle-belt Nigeria, the Verre are one of that populous country’s numerous micro-minorities. -

Assessment of Wind Energy Resources for Electricity Generation Using WECS in North-Central Region, Nigeria

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 15 (2011) 1968–1976 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Contents lists available at ScienceDirect provided by Covenant University Repository Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rser Assessment of wind energy resources for electricity generation using WECS in North-Central region, Nigeria Olayinka S. Ohunakin Mechanical Engineering Department, Covenant University, P.M.B 1023, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria article info abstract Article history: This paper presents a statistical analysis of wind characteristics of five locations covering the North- Received 1 October 2010 Central (NC) geo-political zone, Nigeria, namely Bida, Minna, Makurdi, Ilorin and Lokoja using Weibull Accepted 4 January 2011 distribution functions on a 36-year (1971–2007) wind speed data at 10 m height collected by the mete- orological stations of NIMET in the region. The monthly, seasonal and annual variations were examined Keywords: while wind speeds at different hub heights were got by extrapolating the 10 m data using the power law. Weibull distribution The results from this investigation showed that all the five sites will only be adequate for non-connected Wind energy conversion systems electrical and mechanical applications with consideration to their respective annual mean wind speeds Mean wind speeds Wind energy of 2.747, 4.289, 4.570, 4.386 and 3.158 m/s and annual average power densities of 16.569, 94.113, 76.399, 2 Nigeria 71.823 and 26.089 W/m for Bida, Minna, Makurdi, Ilorin and Lokoja in that order. -

AUTHOR TITLE Adult Forces

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 059 416 AC 012 155 AUTHOR Nasution, Amir H. TITLE Foreign Assistance Contribution in AdultEducation in Nigeria. INSTITUTION Ibadan Univ. (Nigeria). Inst. of AfricanAdult Education. PUB DATE Mar 71 NOTE 25p.; Paper presented to Nigerial NationalConference on Adult Education (March25-27, 1971, Lagos Univ., Lagos) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Administrative Personnel; *Adult Education;Community Agencies (Public) ;*Conferences; *Cooperative Programs; *Educational Finance; EducationalNeeds; Federal Programs; *Financial Support;*Foreign Countries; Group Activities; Mass Instruction; Organizations (Groups); Planning; PrivateAgencies; State Programs IDENTIFIERS Af r ica; *Nigeria ABSTRACT The proceedings of a nation-wideconference in Nigeria concerning adult education arepresented. The following steps are proposed in the line ofnational and international cooperation; these steps can be taken without waitingfor financial and administrative approval:(1) the registration of all kinds ofadult education programs and activities carried outby public as well as private agencies;(2) involvement of all educationpersonnel in the planning organization, and establishment of anEducation Planning Unit; (3) the formation of adult educationpriority programs, with supporting services, mass education meansand libraries, to be assisted in the context of Federal and Statesset of priorities and potentialities; and (4)the mobilization of private funds andforces on behalf of adult education.(Author/CK) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEENREPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OFEDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY. C) e--I FORE'IGNASSISTANCE CONTRIBUTION. I N LC\ ADULT EDUCATION IN NIGERIA LIJ By Amir H. -

From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940

The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History ISSN: 0308-6534 (Print) 1743-9329 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fich20 From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940 Samuel Fury Childs Daly To cite this article: Samuel Fury Childs Daly (2019) From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 47:3, 474-489, DOI: 10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 Published online: 15 Feb 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 268 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fich20 THE JOURNAL OF IMPERIAL AND COMMONWEALTH HISTORY 2019, VOL. 47, NO. 3, 474–489 https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2019.1576833 From Crime to Coercion: Policing Dissent in Abeokuta, Nigeria, 1900–1940 Samuel Fury Childs Daly Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Indirect rule figured prominently in Nigeria’s colonial Nigeria; Abeokuta; crime; administration, but historians understand more about the police; indirect rule abstract tenets of this administrative strategy than they do about its everyday implementation. This article investigates the early history of the Native Authority Police Force in the town of Abeokuta in order to trace a larger move towards coercive forms of administration in the early twentieth century. In this period the police in Abeokuta developed from a primarily civil force tasked with managing crime in the rapidly growing town, into a political implement of the colonial government. -

Palmas, the Last Capital City Planned in Twentieth-Century Brazil

Scientific Article DOI: 10.1590/2175-3369.012.e20190168 Palmas, the last capital city planned in twentieth-century Brazil Palmas, a última capital planejada no Brasil do século XX Renato Leão Rego[a] [a] Universidade Estadual de Maringá (UEM), Maringá, PR, Brasil How to cite: Rego, R. L. (2020). Palmas, the last capital city planned in twentieth-century Brazil. urbe. Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana, 12, e20190168. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-3369.012.e20190168 Abstract Palmas is the capital of a new state created in order to foster regional development in central Brazil. This new town was planned from scratch in 1989, during the country’s re-democratization process, between the postmodernist criticism of functionalist planning and rising environmental concerns. However, its layout depicts a mixed relationship with Brasília-style urbanism. Covering a timeframe of thirty years (1989-2019), this paper presents an outline of the history and planning of Palmas, followed by an assessment of its plan and an exploration of its contemporary major urban challenges. It contrasts the planners’ original ideas with the built city, and unveils late modernist features that have been rejected and transformed. Essentially, Palmas is a modernist new capital city planned in postmodernist times. Keywords: New town. Regional planning. Urban design. Planning diffusion. Developing country. Resumo Palmas é a capital de um novo estado criado no interior do Brasil para fomentar o desenvolvimento regional. Esta nova cidade foi planejada em 1989, durante o processo de redemocratização do país, em meio à crítica ao urbanismo modernista e às crescentes preocupações ambientais. Contudo, seu traçado revela uma relação mista com o urbanismo de Brasília. -

Rail Transportation Data

Rail Transportation Data (Q1 2019) Report Date: May 2019 Data Source: National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) Contents Executive Summary 1 Number of Passengers 2 Volume of Goods/Cargo (Tons) 3 Revenue Generated from Passenger (N) 4 Revenue Generated from Goods/Cargo (N) 5 Other Income Receipt (N) 6 Methodology 7 Definition of Terms 8 Appendix 9 Acknowledgment and Contact 10 Executive Summary The rail transportation data for Q1 2019 reflected that a total of 723,995 passengers travelled via the rail system in Q1 2019 as against 748,345 passenger recorded in Q1 2018 and 746,739 in Q4 2018 representing -3.25% decline YoY and -3.05% decline QoQ respectively. Similarly, a total of 54,099 tons of volume of goods/cargo travelled via the rail system in Q1 2019 as against 79,750 recorded in Q1 2018 and 68,716 in Q4 2018 representing -32.16% decline YoY and -21.27% decline QoQ respectively. Revenue generated from passengers in Q1 2019 was put at N520,794,143 as against N507,495,503 in Q4 2018. Similarly, revenue generated from goods/cargo in Q1 2019 was put at N102,585,926 as against N84,408,861 in Q4 2018. 1 Rail Transportation Data - Q1 2019 Rail Transportation Data - Q1 2019 Number of Passengers 2019 Q on Q Y on Y % Change QRT 1 % Change (3.05) 723,995 (3.25) 2018 QRT 1 QRT 2 QRT 3 QRT 4 748,345 730,289 794,316 746,739 TOTAL 3,019,689 12 Rail Transportation Data - Q1 2019 Rail Transportation Data - Q1 2019 Volume of Goods/Cargo (Tons) 2019 Q on Q Y on Y % Change QRT 1 % Change (21.27) 54,099 (32.16) 2018 QRT 1 QRT 2 QRT 3 QRT 4 79,750 85,816 94,352