The Vegetation of the Pig Rootled Areas at Knepp Wildland and Their Use by Farmland Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scholarship Boys and Children's Books

Scholarship Boys and Children’s Books: Working-Class Writing for Children in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s Haru Takiuchi Thesis submitted towards the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics, Newcastle University, March 2015 ii ABSTRACT This thesis explores how, during the 1960s and 1970s in Britain, writers from the working-class helped significantly reshape British children’s literature through their representations of working-class life and culture. The three writers at the centre of this study – Aidan Chambers, Alan Garner and Robert Westall – were all examples of what Richard Hoggart, in The Uses of Literacy (1957), termed ‘scholarship boys’. By this, Hoggart meant individuals from the working-class who were educated out of their class through grammar school education. The thesis shows that their position as scholarship boys both fed their writing and enabled them to work radically and effectively within the British publishing system as it then existed. Although these writers have attracted considerable critical attention, their novels have rarely been analysed in terms of class, despite the fact that class is often central to their plots and concerns. This thesis, therefore, provides new readings of four novels featuring scholarship boys: Aidan Chambers’ Breaktime and Dance on My Grave, Robert Westall’s Fathom Five, and Alan Garner’s Red Shift. The thesis is split into two parts, and these readings make up Part 1. Part 2 focuses on scholarship boy writers’ activities in changing publishing and reviewing practices associated with the British children’s literature industry. In doing so, it shows how these scholarship boy writers successfully supported a movement to resist the cultural mechanisms which suppressed working-class culture in British children’s literature. -

Lawrie & Symington

Lawrie & Symington Ltd Lanark Agricultural Centre Sale of Poultry, Waterfowl and Pigs etc. Thursday 17th March, 2016 Ringstock at 10.30 a.m. General Hall at 11.00 a.m Lanark Agricultural Centre Sale of Poultry and Waterfowl Special Conditions of Sale The Sale will be conducted subject to the Conditions of Sale of Lawrie and Symington Ltd as approved by the Institute of Auctioneers and Appraisers in Scotland which will be on display in the Auctioneer’s office on the day of sale. In addition the following conditions apply. 1. No animal may be sold privately prior to the sale, but must be offered for sale through the ring. 2. Animals which fail to reach the price fixed by the vendor may be sold by Private Treaty after the Auction. All such sales must be passed through the Auctioneers and will be subject to full commission. Reserve Prices should be given in writing to the auctioneer prior to the commencement of the sale. 3. All stock must be numbered and penned in accordance with the catalogued number on arrival at the market. 4. All entries offered for sale must be pre-entered in writing and paid for in full with the entries being allocated on a first come first served basis by the closing date or at 324 2x2 Cages and/or at 70 3x3 Cages, whichever is earliest. 5. No substitutes to entries will be accepted 10 days prior to the date of sale. Any substitutes brought on the sale day WILL NOT BE OFFERED FOR SALE. 6. -

Animal Genetic Resources Information Bulletin

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Les appellations employées dans cette publication et la présentation des données qui y figurent n’impliquent de la part de l’Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture aucune prise de position quant au statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs autorités, ni quant au tracé de leurs frontières ou limites. Las denominaciones empleadas en esta publicación y la forma en que aparecen presentados los datos que contiene no implican de parte de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación juicio alguno sobre la condición jurídica de países, territorios, ciudades o zonas, o de sus autoridades, ni respecto de la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and the extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. Tous droits réservés. Aucune partie de cette publication ne peut être reproduite, mise en mémoire dans un système de recherche documentaire ni transmise sous quelque forme ou par quelque procédé que ce soit: électronique, mécanique, par photocopie ou autre, sans autorisation préalable du détenteur des droits d’auteur. -

JAHIS 病理・臨床細胞 DICOM 画像データ規約 Ver.2.0

JAHIS標準 13-005 JAHIS 病理・臨床細胞 DICOM 画像データ規約 Ver.2.0 2013年6月 一般社団法人 保健医療福祉情報システム工業会 検査システム委員会 病理・臨床細胞部門システム専門委員会 JAHIS 病理・臨床細胞 DICOM 画像データ規約 ま え が き 院内における病理・臨床細胞部門情報システム(APIS: Anatomic Pathology Information System) の導入及び運用を加速するため、一般社団法人 保健医療福祉情報システム工業会(JAHIS)では、 病院情報システム(HIS)と病理・臨床細胞部門情報システム(APIS)とのデータ交換の仕組みを 検討しデータ交換規約(HL7 Ver2.5 準拠の「病理・臨床細胞データ交換規約 Ver.1.0」)を作成 した。 一方、医用画像の標準規格である DICOM(Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) においては、臓器画像と顕微鏡画像、WSI(Whole Slide Images)に関する規格が制定された。 しかしながら、病理・臨床細胞部門では対応実績を持つ製品が未だない実状に鑑み、この規格 の普及を促進すべく、まず、病理・臨床細胞部門で多く扱われている臓器画像と顕微鏡画像の規 約を 2012 年 2 月に「病理・臨床細胞 DICOM 画像データ規約 Ver.1.0」として作成した。 そして、近年、バーチャルスライドといった新しい製品の投入により、病理・臨床細胞部門に おいても大規模な画像が扱われるようになり、本規約書に WSI に関する規格の追加が急がれ、こ こに Ver.2.0 として発行する運びとなった。 本規約をまとめるにあたり、ご協力いただいた関係団体や諸先生方に深く感謝する。本規約が 医療資源の有効利用、保健医療福祉サービスの連携・向上を目指す医療情報標準化と相互運用性 の向上に多少とも貢献できれば幸いである。 2013年6月 一般社団法人 保健医療福祉情報システム工業会 検査システム委員会 << 告知事項 >> 本規約は関連団体の所属の有無に関わらず、規約の引用を明示することで自由に使用す ることができるものとします。ただし一部の改変を伴う場合は個々の責任において行い、 本規約に準拠する旨を表現することは厳禁するものとします。 本規約ならびに本規約に基づいたシステムの導入・運用についてのあらゆる障害や損害 について、本規約作成者は何らの責任を負わないものとします。ただし、関連団体所属の 正規の資格者は本規約についての疑義を作成者に申し入れることができ、作成者はこれに 誠意をもって協議するものとします。 © JAHIS 2013 i 目 次 1. はじめに .............................................................................................................................. 1 2. 適用範囲 .............................................................................................................................. 2 3. 引用規格・引用文献 ........................................................................................................... -

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state. -

TT Autumn 11

The Tamworth Breeders’ Club Autumn 2011 Volume 6, Issue 1 TamworthTamworth Tamworths - The future’s orange! TrumpetTrumpet New Club Secretary Lucy has decided to relinquish being Tamworth secretary owing to changed circumstances in her life- style which have severely reduced the amount of time available for her to do the job as she wanted. She has done an enormous amount for us over the past year not least completely revising and updat- ing the membership list and determining who was and who was not paid up! Inside this issue: She also oversaw the revamping of our website transferring the domain to the club’s ownership and control. Not least she has been very patiently dealing with members queries and problems, some of Tamworth Trifles 2 which were far from easy going to sort out. We are very grateful to her for putting such a lot of her time into the role and are delighted that she intends to continue her membership. We shall also look Chairman’s Message 3 forward to seeing her in her position at the Royal Berks Show which she undertakes with great finesse 25 Years with Tammys 4-5 and success each year. Thank you Lucy for being there for us at a difficult time. Howes ‘At! 6 We are very lucky to have found someone to take over from Tammys in NZ 7 Lucy and here is an introduction in her own words: My name is Michele Baldock, and I live on a smallholding on New Book 8 the Romney Marsh in Kent with my husband Mark and two daughters Florence & Edie. -

Snomed Ct Dicom Subset of January 2017 Release of Snomed Ct International Edition

SNOMED CT DICOM SUBSET OF JANUARY 2017 RELEASE OF SNOMED CT INTERNATIONAL EDITION EXHIBIT A: SNOMED CT DICOM SUBSET VERSION 1. -

5-6 Booklist by Author - Short

5-6 Booklist by Author - Short When using this booklist, please be aware of the need for guidance to ensure students select texts considered appropriate for their age, interest and maturity levels. PRC Author Title 227 Aaron, Moses Lily and me 1245 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Friendship matchmaker goes undercover, The 51994 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Friendship matchmaker, The 1590 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Jodie: this is the book of you 5054 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Rania: this is the book of you 23 Abdulla, Ian As I grew older 426 Abdulla, Ian Tucker Abela, Deborah Ghost club series Abela, Deborah Grimsdon series Abela, Deborah Max Remy super spy series 23491 Abela, Deborah Most marvellous spelling bee mystery, The 11382 Abela, Deborah Remarkable secret of Aurelie Bonhoffen, The 33584 Abela, Deborah Stupendously spectacular spelling bee, The 1885 Abela, Deborah Teresa, a new Australian Abela, Deborah & Warren, Johnny Jasper Zammit series 312 Adams, Jeanie Pigs and honey Adornetto, Alexandra Strangest adventures series 5446 Agard, John & Packer, Neil (ill) Book 22779 Ahlberg, Allan & Ingman, Bruce Previously 74282 Ahlberg, Allan & Ingman, Bruce (ill) Pencil, The 1136 Alexander, Goldie eSide 7714 Alexander, Goldie Hanna: my Holocaust story 32350 Alexander, Goldie My horrible cousins and other stories 26544 Alexander, Goldie Neptunia 526 Alexander, Goldie & Hamill, Dion Starship Q 30/09/21 5:05 PM 5-6 Booklist by Author - Short Page 1 of 59 PRC Author Title 18498 Alexander, Goldie & Hamill, Dion (ill) Cow-pats 18462 Alexander, Jenny Bullies, bigmouths and so-called -

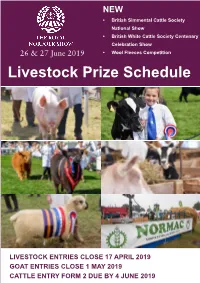

Livestock Prize Schedule

ROYAL NORFOLK SHOW - COMPETITIONS 2019 NEW • British Simmental Cattle Society LIVESTOCK Entries Close: Livestock: 17 April 2019, Goats: 1 May 2019 National Show Holly Whitaker, Royal Norfolk Agricultural Association, Norfolk Showground, Dereham Road, Norwich, Norfolk. NR5 0TT. T: 01603 731965 E: [email protected] • British White Cattle Society Centenary EQUINE Celebration Show Entries Close: 17 April 2019, Showjumping: 29 May 2019 • Wool Fleeces Competition Maria Skitmore, Royal Norfolk Agricultural Association, Norfolk Showground, Dereham Road, Norwich, 26 & 27 June 2019 Norfolk. NR5 0TT. T: 01603 731963 E: [email protected] SMALL LIVESTOCK (Rabbit, Cavy, Poultry and Egg Sections) Entries Close: 24 May 2019 Mrs Jackie Hayes, 13 Brundish Road, Raveningham, Norfolk, NR14 6NT Livestock Prize Schedule T: 01508 548144 E: [email protected] or Holly Whitaker, Royal Norfolk Agricultural Association, Norfolk Showground, Dereham Road, Norwich, Norfolk. NR5 0TT. T: 01603 731965 E: [email protected] YOUNG FARMERS STOCK JUDGING COMPETITIONS Entries Close: 3 May 2019 Details from Norfolk Young Farmers Office, Easton College, Easton, Norwich, Norfolk, NR9 5DX. T: 01603 731307 E: [email protected] STOCKMEN'S STOCKJUDGING COMPETITIONS Entries Close: 10 May 2019 Holly Whitaker, Royal Norfolk Agricultural Association, Norfolk Showground, Dereham Road, Norwich, Norfolk. NR5 0TT. T: 01603 731965 E: [email protected] NORMAC FARM MACHINERY COMPETITIONS Entries Close: 3 May 2019 Mr Chris Thomas, Tunbeck Farm, Wortwell, Nr. Harleston, Norfolk IP20 0HP. T: 01986 788 209 or 07968 665 761 Royal Norfolk Agricultural Association Norfolk Showground, Dereham Road Norwich, Norfolk NR5 OTT T 01603 748931 www.rnaa.org.uk Registered Office as above. -

Download the Newsletter Here

Heavy Horse Musical Drive & Heavy Horse Village Free Fall Red Devils We are excited to be joined by the Parachute Regiment Freefall Team, This year we are pleased to be welcoming Heavy Horses to the Show. the official parachute display team of both The Parachute Regiment and They will perform a Musical Drive in the Main Ring as well as having the British Army. their own classes. The horses will be traditionally turned out with their They will perform a spectacular display above the Main Ring on both manes and tails braided while their drivers will be elegantly dressed. Show days. Set to stirring traditional music, the Musical Drive will involve complex moves including figures of eight and scissor movements. When not in the Main Ring, these horses will be located in the Heavy Horse Village and members and visitors will be able to watch exhibi- The Corps of Commissionaires are looking tors preparing them and see these gentle giants up close. after the Members Area at this year’s Show. They will provide high calibre, well trained The Dorset Watercress Company, our Security Industry Authority licensed profes- local supplier of this traditional super sionals. food, are building—YES building—a fea- A new Flock Competition has been ture in the Floral Pavilion of watercress organised for this year. This is open beds since 1840 to to any flock in Dorset and will be held help us celebrate in June. For more details or to enter, our 175 years anni- contact Rebecca in the office on versary. The Horse & Pony Schedule has been altered for this 01305 264249 or competi- year and there is the addition of some local classes [email protected] This really is one as well as Heavy Horse classes. -

UK National Action Plan on Farm Animal Genetic Resources November 2006 Front Cover Photos: Top Left: Holstein Cattle Grazing (Courtesy of Holstein UK)

UK National Action Plan on Farm Animal Genetic Resources November 2006 Front Cover Photos: Top Left: Holstein cattle grazing (Courtesy of Holstein UK). Top Right: British Milk Sheep halfbred with triplets (Courtesy of Lawrence Alderson). Bottom Left: Tamworth pig in bracken (Courtesy of Dunlossit Estate, Islay). Bottom Right: Red Dorking male (Photograph by John Ballard, Courtesy of The Cobthorn Trust). UK National Action Plan on Farm Animal Genetic Resources November 2006 Presented to Defra and the Devolved Administrations by the National Steering Committee for Farm Animal Genetic Resources UK National Action Plan on Farm Animal Genetic Resources Contents Foreword 3 1. Executive Summary 4 1.1. Overview 4 1.2. List of recommended actions 4 2. Introduction 11 2.1. Why we need to protect our Farm Animal Genetic Resources 11 2.1.1. Economic, social and cultural importance of the UK’s FAnGR 11 2.1.2. International obligation to protect our FAnGR 14 2.1.3. Impact of national policies on the UK’s FAnGR 14 2.2. Why we need a National Action Plan 15 2.3. Structure of the Plan 16 3. What, and where, are our Farm Animal Genetic Resources? 17 3.1. Introduction 17 3.2. Identification of the UK’s Farm Animal Genetic Resources 17 3.2.1. Describing breeding population structures 17 3.2.2. Creating a UK National Breed Inventory 19 3.2.3. Definition of a breed 19 3.2.4. Characterisation 20 3.2.5. Molecular characterisation 21 3.3. Monitoring 21 3.3.1. Monitoring breeds 22 3.3.2. -

Pig Disease: Similar to Humans, Swine Need to Have Some Basic Living Standards Met in Order to Stay Healthy

ANR Publication 8482 | April 2014 http://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu SWINE:From the Animal’s Point of View 4 SUBJECT OVERVIEW AND BACKGROUND INFORMATION There are several factors that can contribute to the deterioration of a pig’s health, but diseases in these animals usually do not occur “out of nowhere.” Illnesses and diseases frequently happen when a pig experiences stress, has a poor diet, is exposed to other pigs that are ill, consumes contaminated food or water, or is housed in an inappropriate environment (i.e., too hot, unsanitary). Some common diseases are pneumonia, pseudo rabies (mad itch), and swine dysentery. Swine can also have external parasites such as lice and mange mites or internal parasites that live inside the pig’s body. Pig Disease: Similar to humans, swine need to have some basic living standards met in order to stay healthy. Having the right diet What You Need to Know is crucial to a pig’s health. A pig that is malnourished is more vulnerable to disease. The immune system of a malnourished animal has a harder time fighting off pathogens (e.g., disease- causing bacteria or viruses) than that of a well-nourished animal, so disease is more likely to take over the underfed pig’s body and bring about still more health problems. A healthy MARTIN H. SMITH, Cooperative Extension Youth Curriculum Development Specialist, University of California, Davis; CHERYL L. diet can prevent myriad diseases. MEEHAN, Staff Research Associate, UC Davis; JUSTINE M. MA, Program Representative, UC Davis; NAO HISAKAWA, Student Assistant, Veterinary Medicine Extension, UC Davis; H.