Criminalizing Humanitarian Intervention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE AD HOC TRIBUNALS ORAL HISTORY PROJECT an Interview

THE AD HOC TRIBUNALS ORAL HISTORY PROJECT An Interview with Benjamin B. Ferencz International Center for Ethics, Justice and Public Life Brandeis University 2015 RH Session One Interviewee: Benjamin B. Ferencz Location: Waltham, MA Interviewers: David P. Briand (Q1) and Date: 7 November 2014 Leigh Swigart (Q2) Q1: This is an interview with Benjamin B. Ferencz for the Ad Hoc Tribunals Oral History Project at Brandeis University’s International Center for Ethics, Justice and Public Life. The interview takes place at the Ethics Center offices in Waltham, Massachusetts on November 7, 2014. The interviewers are Leigh Swigart and David Briand. Ferencz: I hope I don't disappoint you, because I know very little about the temporary [United Nations] Security Council tribunals. I know a lot about the ICC [International Criminal Court], I know a lot about what the world needs, I know what we have to build on, so if my answers to your questions appear to be wandering off a bit it's because there is a message that I want to deliver. It's a message which is consistent, which I hope would be approved by Brandeis, certainly, and also by the members of the staff, and that is we're trying to get a more humane and peaceful world governed by the rule of law. This is my guiding star. I'm ninety-five years old. I'm going to start my ninety-sixth year in a few months. I'm happily wed to a girl also from Transylvania, who is also the same age—a little bit older. -

Recent Segments the World to Know Deported at 97, Ben Ferencz Is the Last Nuremberg Prosecutor Alive and He Has a Far- Reaching Message for Today’S World

CBS News / CBS Evening News / CBS This Morning / 48 Hours / 60 Minutes / Sunday Morning / Face The Nation / CBSN Log In Search Episodes Overtime Topics The Team 60 Minutes All Access RELATED VIDEO NEWSMAKERS The Nuremberg Prosecutor 60 MINUTES OVERTIME When Ben Ferencz met Marlene Dietrich 60 MINUTES OVERTIME Ferencz: Rejecting refugees is a "crime against humanity" 60 MINUTES OVERTIME Nuremberg prosecutor, haunted What the last Nuremberg prosecutor alive wants the world to know Recent Segments the world to know Deported At 97, Ben Ferencz is the last Nuremberg prosecutor alive and he has a far- reaching message for today’s world 2017 CORRESPONDENT COMMENTS FACEBOOK TWITTER STUMBLE May 07 Lesley Stahl 164 Theo and Joe Twenty-two SS officers responsible for the deaths of 1M+ people would never have been brought to justice were it not for Ben Ferencz. The officers were part of units called Einsatzgruppen, or action groups. Their job was to follow the German army as it invaded the Soviet Union in 1941 and The Nuremberg kill Communists, Gypsies and Jews. Prosecutor Ferencz believes "war makes murderers out of otherwise decent people" and has spent his life working to deter war and war crimes. Starr Students Norman Seeff's Archive Ben Ferencz / CBS NEWS It is not often you get the chance to meet a man who holds a place in history like Ben Ferencz. He's 97 years old, barely 5 feet tall, and he served as prosecutor of what's been called the biggest murder trial ever. The courtroom was Nuremberg; the crime, genocide; the defendants, a group of German SS officers accused of committing the largest number of Nazi killings outside the concentration camps -- more than a million men, women, and children shot down in their own towns and villages in cold blood. -

Case Global 25Celebrating News from the International Law Center & Institutes Years

v. 7 no. 1 2015 Case Global 25Celebrating News from the International Law Center & Institutes Years Changing lives over spring break Students, alumna journey to Dilley, TX to provide legal help to undocumented refugees in detention center hen three Case Western Reserve highlighted the plight of the families held University School of Law students at the South Texas Family Residential Wentered their immigration law Center in Dilley, Texas, Madeline Jack, Dozens of mothers and class one February evening, they had no Harrison Blythe, and JoAnna Gavigan idea how much their legal education would quickly agreed to spend their spring break children released as a be put to the test to help undocumented assisting Peyton and her Ohio team result of the team’s women and children detained by U.S. in bringing legal representation to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement detained women and children. work during spring in a for profit prison run by Corrections Corporation of America. Thanks to the generous financial break. support from the Case Western Reserve But once instructor and Cleveland immigration attorney Jennifer Peyton Continued on page 7 Ranked 11th in the nation by U.S. News & World Report ABOUT THE FREDERICK K. COX INTERNATIONAL LAW CENTER We are pleased to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the endowment of our Frederick K. Cox International Law Center this year. This issue of Case Global News includes a timeline of our major milestones on the way to becoming the #11th ranked international law program in the country. The newsletter also provides an update on the activities of our international law program and its 30 associated faculty members, as well as a preview of our upcoming lectures and conferences. -

From Nuremberg to Now: Benjamin Ferencz's

“Are you going to help me save the world?” From Nuremberg to Now: Benjamin Ferencz’s Lifelong Stand for “Law. Not War.” Creed King and Kate Powell Senior Division Group Exhibit Student-composed Words: 493 Process Paper: 500 words Process Paper Who took a stand for the Jews after World War II? Pondering this compelling question, we stumbled upon the story of Benjamin Ferencz. As a young lawyer, Ferencz convinced fellow attorneys at the Nuremberg Trials to prosecute the Einsatzgruppen, Hitler’s roving extermination squads, in the “biggest murder trial of the century” (Tusa). Ferencz convicted all twenty-two defendants, then parlayed his Nuremberg experience into a lifelong stand for world peace through the application of law. Our discovery that Ferencz, at age ninety-seven, is the last living Nuremberg prosecutor – and living in our home state – led to a remarkable interview. We began by researching primary sources such as oral histories and evidence gathered after the war by the War Crimes Branch of the US Army and compared these to personal accounts archived by the Florida State University Institute on World War II. Reading memos and logbooks kept by the Nazis helped us understand the significance of Ferencz’s stand at Nuremberg. Ferencz’s papers provided interviews, photographs, and documents to corroborate historical data and underscore his lifelong advocacy for peace. For a firsthand perspective, we conducted several personal interviews. Talking with Ferencz about his transformation from prosecutor to modern activist for world peace and Zelda Fuksman on surviving the Holocaust and her perspective on the Nuremberg Trials were two crucial pieces of research. -

SCSL Press Clippings

SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE PRESS AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE PRESS CLIPPINGS Enclosed are clippings of local and international press on the Special Court and related issues obtained by the Press and Public Affairs Office as at: Wednesday, 18 April 2007 Press clips are produced Monday through Friday. Any omission, comment or suggestion, please contact Martin Royston-Wright Ext 7217 2 Local News The Transfer of Charles Taylor to The Hague: A Cause To Rethink / The News Page 3 Salone To Look Into US Human Rights Reports / Awoko Page 4 International News UNMIL Public Information Office Media Summary / UNMIL Pages 5-6 Ex-Liberian President's Associate Cries Foul / Afrol News Page 7 Visit Taylor at The Hague / Fortaylor.net Page 8 A Tribute Paid to Reason / The Walrus Magazine Pages 9-17 3 The News Wednesday, 18 April 2007 4 Awoko Wednesday, 18 April 2007 5 United Nations Nations Unies United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) UNMIL Public Information Office Media Summary 17 April 2007 [The media summaries and press clips do not necessarily represent the views of UNMIL.] International Clips on Liberia Liberia plans security force to replace UN peacekeepers MONROVIA, April 16, 2007 (AFP) - The government of Liberia plans to set up a rapid reaction force to quell any riots when UN peacekeeping troops pull out, the information minister said Monday. "This unit will assume duty upon the departure of the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL)," Lawrence Bropleh said in a statement. International Clips on West Africa AP 04/16/2007 17:42:16 Ivory Coast president, rebel chief start dismantling buffer zone PARFAIT KOUASSI ABIDJAN, Ivory Coast - With a ceremonial bulldozing of a wooden barricade, Ivory Coast's president and the man who tried to unseat him in a violent rebellion started Monday to dismantle the U.N.-patrolled buffer zone that has split the country since an attempted 2002 coup sparked civil war. -

Accountability for the Illegal Use of Force – Will the Nuremberg Legacy Be Complete?

VOLUME 58, ONLINE JOURNAL, SPRING 2017 Accountability for the Illegal Use of Force – Will the Nuremberg Legacy Be Complete? In 1946, the world witnessed the first-ever prosecutions of a state’s leaders for planning and executing a war of aggression. The idea of holding individuals accountable for the illegal use of force—the “supreme international crime”—was considered but ultimately rejected in the wake of the First World War.1 A few decades later, however, following the even more destructive Second World War, the victorious powers succeeded in coming together in a court of law at Nuremberg to prosecute the leaders of Nazi Germany for waging an aggressive war against other states. Yet the Nuremberg trials were both the first and last time an international tribunal has adjudicated aggression. It took decades for the international community to take the steps necessary to institutionalize the prosecution of international crimes and to reconfirm the prohibition on aggression as a crime under international law.2 Now, in 2017—seventy years after the Nuremberg prosecutions—the international community will gather to decide whether to activate the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC) over the crime of aggression.3 Over seven decades, as the international community has debated how and whether to make the prosecution of aggression a practical reality, Benjamin Ferencz has worked tirelessly to ensure that the prevention and prosecution of aggressive war-making remain on the international agenda. As the Chief Prosecutor in the Einsatzgruppen case, Ferencz secured the convictions of twenty- two SS officers for the murders of over one million Jews, Roma, disabled persons, partisans, and others.4 Between 1947 and 1957, as the Director of the Jewish Restitution Successor Organization and through the United Restitution Organization, he helped Jewish victims recover lost property, and through the 1 22 TRIAL OF THE MAJOR WAR CRIMINALS BEFORE THE INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL, NUREMBERG 427 (1948). -

Watchers of the Sky

Presents Watchers of the Sky A film by Edet Belzberg 120 min., 2014 Rated TBD Press materials: http://www.musicboxfilms.com/watchersofthesky-press Official site: http://www.musicboxfilms.com/watchersofthesky Music Box Films Marketing & Publicity Distribution Contact: Brian Andreotti: [email protected] Andrew Carlin Rebecca Gordon: [email protected] [email protected] 312-508-5361/ 312-508-5362 312-508-5360 NY Publicity: LA Publicity: Susan Norget Film Promotion Laemmle Theatres Susan Norget Jordan Moore 212-431-0090 (310) 478-1041 x 208 [email protected] [email protected] SYNOPSIS With his provocative question, “why is the killing of a million a lesser crime than the killing of an individual?” Raphael Lemkin changed the course of history. An extraordinary testament to one man’s perseverance, the Sundance award- winning film Watchers of the Sky examines the life and legacy of the Polish- Jewish lawyer and linguist who coined the term genocide. Before Lemkin, the notion of accountability for war crimes was virtually non-existent. After experiencing the barbarity of the Holocaust firsthand, he devoted his life to convincing the international community that there must be legal retribution for mass atrocities targeted at minorities. An impassioned visionary, Lemkin confronted world apathy in a tireless battle for justice, setting the stage for the Nuremberg trials and the creation of the International Criminal Court. Inspired by Samantha Power’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book A Problem From Hell, this multi-faceted documentary interweaves Raphael Lemkin’s struggle with the courageous efforts of four individuals keeping his legacy alive: Luis Moreno Ocampo, Chief Prosecutor of the ICC; Samantha Power, U.S. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E323 HON

March 21, 2019 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E323 may not have had the pleasure of knowing cancy Reduction Act. This bill would allow In January of 1942, Richard enlisted in the him will benefit for years to come because of local District of Columbia court nominees to be United States Navy. He trained in aviation the extra first response vehicles that he seated after a 30-day congressional review radio at Naval Air Station Banana River, now helped secure for the Fire Department and the period unless a resolution of disapproval is en- called Patrick Air Force Base. He worked con- drivers education cars that he worked to pro- acted into law during that period. Currently, voy coverage and submarine patrol and was a vide for the local schools. nominees cannot be seated without affirmative part of the Helicopter Development Squadron. All these amazing things that Chief Bill John Senate approval. The congressional review While in service, he traveled to Brazil where Baker had a hand in, ultimately help raise process for nominees would be the same one he was stationed for three and a half months. awareness of the Cherokee people and their used for legislation passed by the D.C. Coun- Other assignments in Brazil took him to Aratu presence in Northeastern Oklahoma. I con- cil. It is therefore a reliable process, long-rec- and Natal. In Natal, Richard worked the radio gratulate Chief Baker on his retirement, as it ognized by Congress. My bill is prompted by one night for so long that he became deaf and is well deserved. -

Fall 2020 Newsletter

NEWSLETTER FALLFall 20202018 THE AGE OF ROBERT H. JACKSON On August 8th the Robert H. Jackson Center hosted a free global webinar celebrating the 75th anniversary of the signing of the London Agreement and Charter and the establishment of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. Moderated by Michael Scharf, Dean and Joseph C. Hostetler-BakerHostetler Professor of Law at Case Western Reserve University School of Law, guests included: • Ben Ferencz, Investigator of Nazi war crimes & the chief prosecutor for the United States Army at the Einsatzgruppen Trial • John Q. Barrett, Professor of Law at St. John’s University, Elizabeth S. Lenna Fellow and Board member at the Robert H. Jackson Center • David Crane, Founding Chief Prosecutor, Special Court for Sierra Leone • James Johnson, Prosecutor, Residual Special Court for Sierra Leone • Leila Sadat, Director, Whitney R. Harris World Law Institute and Special Adviser on Crimes Against Humanity to the ICC Prosecutor, James Carr Professor of International Criminal Law • Mark Ellis, Executive Director, International Bar Association • William A. Schabas, OC MRIA, Professor of International Law, School of Law, Middlesex University, London, Professor of International Criminal Law and Human Rights at Leiden University • Navi Pillay, President of the Advisory Council, International Nuremberg Principles Academy • Klaus Rackwitz, Director, International Nuremberg Principles Academy They discussed how the legacy of Robert H. Jackson and the Nuremberg Trials live in the world today. “Law is better than war,” said Ben Ferencz in his opening remarks. “We must substitute for the use of armed force with peaceful means only…that idea is in jeopardy today.” Further discussion ensued on Jackson’s opening statement at Nuremberg as Chief Prosecutor for the United States and its influence on international criminal law. -

Extensions of Remarks E324 HON. ANDY KIM HON

E324 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks March 21, 2019 HONORING MS. MELISSA crimes investigator. He entered many Nazi thousands of animals he has cared for along ANTINOFF ON BEING NAMED concentration camps as they were liberated the way. BURLINGTON COUNTY’S TEACH- and the horrors he saw made an indelible im- f ER OF THE YEAR BY THE NEW pression. When he returned home, he was re- JERSEY DEPARTMENT OF EDU- cruited by General Telford Taylor to return to HONORING MS. DELINA CATION Germany to help in the additional war crimes RODRIGUES OF CARBON COUNTY trials. HON. ANDY KIM He was appointed Chief Prosecutor in what HON. DANIEL MEUSER OF NEW JERSEY was aptly described as the biggest murder trial OF PENNSYLVANIA IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES in history—the ‘‘Einsatzgreuppen case.’’ All 22 IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES defendants, including six SS Generals, were Thursday, March 21, 2019 Thursday, March 21, 2019 convicted of murdering over a million innocent Mr. KIM. Madam Speaker, I rise today to men, women, and children. Ben was 27 years Mr. MEUSER. Madam Speaker, I rise today recognize Ms. Melissa Antinoff, a devoted ed- old and it was his first case. to recognize and honor Ms. Delina Rodrigues ucator who has helped shape the minds of Since then, Ben has dedicated much of his of Carbon County, who represented the United New Jersey’s youth throughout her 19 years life to seeking compensation for victims and States at the Special Olympics World Games as a public school teacher. Ms. Antinoff was trying to prevent illegal war-making. -

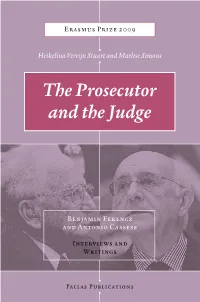

The Prosecutor and the Judge

From Nuremberg and Tokyo Erasmus Prize 2009 to The Hague and Beyond ¶ verrijn stuart | simons Heikelina Verrijn Stuart and Marlise Simons benjamin ferencz, investigator of Nazi war crimes and prosecutor at Nuremberg. Author and lecturer. antonio cassese, first president of the Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and president of the Special Tribunal for Lebanon. The Prosecutor The prestigious Praemium Erasmianum 2009 was awarded to Benjamin Ferencz and Antonio Cassese, who embody the history of international criminal law from and the Judge Nuremberg to The Hague. The Prosecutor and the Judge is a meeting with these two remarkable men through in depth interviews by Heikelina Verrijn Stuart and Marlise Simons about their judge and the e prosecutor ¶ work and ideas, about the war crimes trials, human cruelty, the self-interest of states; about remorse in the courtroom, about restitution and compensation for th victims and about the strength and the limitations of the international courts. Heikelina Verrijn Stuart is a lawyer and philosopher of law who has published extensively on international humanitarian and criminal law and on remorse, revenge and forgiveness. Since 1993 she has followed the international courts and tribunals for radio and television. Marlise Simons is a correspondent for The New York Times, who has written on conflicts and political murder, torture and disappearances from Latin America. For more than a decade, she has reported on international courts and tribunals in The Hague. Benjamin Ferencz and Antonio Cassese Interviews -

Seeking Redress for Hitler's Victims

chapter 4 Seeking Redress for Hitler’s Victims: Personal Remembrances Benjamin B. Ferencz, with Michael J. Bazyler and Kristen L. Nelson Introduction Among Ben Ferencz’s multitude of achievements, in his almost 100 years of unflagging service to combating injustice and promoting world peace, the in- ternational community knows him best as an icon of Nuremberg. Ben was the Chief Prosecutor of the Einsatzgruppen trial, a trial the Associated Press called ‘the biggest murder trial in history.’1 Now in his 99th year, Ben is Nuremberg’s last living prosecutor. There is, however, another aspect to Ben’s remarkable life of which most are unaware. After Nuremberg, Ben stayed in Europe and spent the immedi- ate postwar years fighting for reparations and restitution on behalf of Hitler’s victims, Jews and non- Jews alike. Ben’s wife Gertrude joined him, and all their four children were born in Germany. Ben’s efforts included holding industri- alists accountable for the slave labour used in factories during World War ii. His efforts to hold the German industrialists civilly accountable is evocatively recorded in his book Less Than Slaves, first published in 1979.2 For reasons revealed here, the lack of publicity at the time for these resti- tution efforts was deliberate. In this chapter, Ben now reflects on some of the greatest restitution measures ever to come out of a post- conflict situation, a testament to individuals like him who sought not only criminal justice but also civil justice. Efforts at Holocaust restitution continue to this very day and build upon the achievements that took place after Germany’s defeat in 1945.