Proceedings of the Second International Humanitarian Law Dialogs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE AD HOC TRIBUNALS ORAL HISTORY PROJECT an Interview

THE AD HOC TRIBUNALS ORAL HISTORY PROJECT An Interview with Benjamin B. Ferencz International Center for Ethics, Justice and Public Life Brandeis University 2015 RH Session One Interviewee: Benjamin B. Ferencz Location: Waltham, MA Interviewers: David P. Briand (Q1) and Date: 7 November 2014 Leigh Swigart (Q2) Q1: This is an interview with Benjamin B. Ferencz for the Ad Hoc Tribunals Oral History Project at Brandeis University’s International Center for Ethics, Justice and Public Life. The interview takes place at the Ethics Center offices in Waltham, Massachusetts on November 7, 2014. The interviewers are Leigh Swigart and David Briand. Ferencz: I hope I don't disappoint you, because I know very little about the temporary [United Nations] Security Council tribunals. I know a lot about the ICC [International Criminal Court], I know a lot about what the world needs, I know what we have to build on, so if my answers to your questions appear to be wandering off a bit it's because there is a message that I want to deliver. It's a message which is consistent, which I hope would be approved by Brandeis, certainly, and also by the members of the staff, and that is we're trying to get a more humane and peaceful world governed by the rule of law. This is my guiding star. I'm ninety-five years old. I'm going to start my ninety-sixth year in a few months. I'm happily wed to a girl also from Transylvania, who is also the same age—a little bit older. -

Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context

Goettingen Journal of International Law 2 (2010) 3, 871-892 Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context Jessica Liang Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................ 872 A. Introduction .......................................................................................... 872 B. Superior Orders and the Soldier‘s Dilemma ........................................ 872 C. A Brief History of the Superior Orders Defense under International Law ............................................................................................. 874 D. Alternative Degrees of Attributing Criminal Responsibility: Finding the Right Solution to the Soldier‘s Dilemma ..................................... 878 I. Absolute Defense ................................................................................. 878 II. Absolute Liability................................................................................. 880 III.Conditional Liability ............................................................................ 881 1. Manifest Illegality ..................................................................... 881 2. A Reasonableness Standard ...................................................... 885 E. Frontiers of the Defense: Obedience to Civilian Orders? .................... 889 I. Operation under the Rome Statute ....................................................... 889 II. How far should the Defense of Superior Orders -

Recent Segments the World to Know Deported at 97, Ben Ferencz Is the Last Nuremberg Prosecutor Alive and He Has a Far- Reaching Message for Today’S World

CBS News / CBS Evening News / CBS This Morning / 48 Hours / 60 Minutes / Sunday Morning / Face The Nation / CBSN Log In Search Episodes Overtime Topics The Team 60 Minutes All Access RELATED VIDEO NEWSMAKERS The Nuremberg Prosecutor 60 MINUTES OVERTIME When Ben Ferencz met Marlene Dietrich 60 MINUTES OVERTIME Ferencz: Rejecting refugees is a "crime against humanity" 60 MINUTES OVERTIME Nuremberg prosecutor, haunted What the last Nuremberg prosecutor alive wants the world to know Recent Segments the world to know Deported At 97, Ben Ferencz is the last Nuremberg prosecutor alive and he has a far- reaching message for today’s world 2017 CORRESPONDENT COMMENTS FACEBOOK TWITTER STUMBLE May 07 Lesley Stahl 164 Theo and Joe Twenty-two SS officers responsible for the deaths of 1M+ people would never have been brought to justice were it not for Ben Ferencz. The officers were part of units called Einsatzgruppen, or action groups. Their job was to follow the German army as it invaded the Soviet Union in 1941 and The Nuremberg kill Communists, Gypsies and Jews. Prosecutor Ferencz believes "war makes murderers out of otherwise decent people" and has spent his life working to deter war and war crimes. Starr Students Norman Seeff's Archive Ben Ferencz / CBS NEWS It is not often you get the chance to meet a man who holds a place in history like Ben Ferencz. He's 97 years old, barely 5 feet tall, and he served as prosecutor of what's been called the biggest murder trial ever. The courtroom was Nuremberg; the crime, genocide; the defendants, a group of German SS officers accused of committing the largest number of Nazi killings outside the concentration camps -- more than a million men, women, and children shot down in their own towns and villages in cold blood. -

Nuremberg Academy Annual Report 2018

Annual Report International Nuremberg Principles Academy 1 Imprint The Annual Report 2018 has been Executive Board: published by the International Klaus Rackwitz (Director), Nuremberg Principles Academy. Dr. Viviane Dittrich (Deputy Director) It is available in English, German Edited by: and French and can be ordered Evelyn Müller at [email protected] Layout: or be downloaded on the website Martin Küchle Kommunikationsdesign www.nurembergacademy.org. Photos: Egidienplatz 23 International Nuremberg Principles Academy 90403 Nuremberg, Germany p. 9 Strathmore University, p. 20 Wayamo T + 49 (0) 911.231.10379 Foundation F + 49 (0) 911.231.14020 Printed by: [email protected] Druckwerk oHG Table of Contents 2 Foreword 5 The International Nuremberg Principles Academy 7 A Forum for Dialogue 8 • Events 14 • Network and Cooperation 19 Capacity Building 25 Research 29 Publications and Resources 32 Communications 34 Organization 37 Partners and Sponsors We proudly present the second edition of the Annual Report of the International Nuremberg Principles Academy. It reflects the activities and the achieve ments of the Nuremberg Academy throughout the year of 2018. It was another year of growth for the Nu Foreword remberg Academy with an increased num ber of events and activities at a peak level. Important anniversaries such as the 70th anniversary of the judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and the 20th anniversary of the adoption of the Rome Statute have been reflected in the Academy’s work and activities. Major international conferences – as far as we can see the largest of their kind, dedicated to these important dates worldwide – were held in Nuremberg in May and in October. -

Case Global 25Celebrating News from the International Law Center & Institutes Years

v. 7 no. 1 2015 Case Global 25Celebrating News from the International Law Center & Institutes Years Changing lives over spring break Students, alumna journey to Dilley, TX to provide legal help to undocumented refugees in detention center hen three Case Western Reserve highlighted the plight of the families held University School of Law students at the South Texas Family Residential Wentered their immigration law Center in Dilley, Texas, Madeline Jack, Dozens of mothers and class one February evening, they had no Harrison Blythe, and JoAnna Gavigan idea how much their legal education would quickly agreed to spend their spring break children released as a be put to the test to help undocumented assisting Peyton and her Ohio team result of the team’s women and children detained by U.S. in bringing legal representation to the Immigration and Customs Enforcement detained women and children. work during spring in a for profit prison run by Corrections Corporation of America. Thanks to the generous financial break. support from the Case Western Reserve But once instructor and Cleveland immigration attorney Jennifer Peyton Continued on page 7 Ranked 11th in the nation by U.S. News & World Report ABOUT THE FREDERICK K. COX INTERNATIONAL LAW CENTER We are pleased to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the endowment of our Frederick K. Cox International Law Center this year. This issue of Case Global News includes a timeline of our major milestones on the way to becoming the #11th ranked international law program in the country. The newsletter also provides an update on the activities of our international law program and its 30 associated faculty members, as well as a preview of our upcoming lectures and conferences. -

Nuremberg Icj Timeline 1474-1868

NUREMBERG ICJ TIMELINE 1474-1868 1474 Trial of Peter von Hagenbach In connection with offenses committed while governing ter- ritory in the Upper Alsace region on behalf of the Duke of 1625 Hugo Grotius Publishes On the Law of Burgundy, Peter von Hagenbach is tried and sentenced to death War and Peace by an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges representing differ- ent local polities. The crimes charged, including murder, mass Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, one of the principal rape and the planned extermination of the citizens of Breisach, founders of international law with such works as Mare Liberum are characterized by the prosecution as “trampling under foot (On the Freedom of the Seas), publishes De Jure Belli ac Pacis the laws of God and man.” Considered history’s first interna- (On the Law of War and Peace). Considered his masterpiece, tional war crimes trial, it is noted for rejecting the defense of the book elucidates and secularizes the topic of just war, includ- superior orders and introducing an embryonic version of crimes ing analysis of belligerent status, adequate grounds for initiating against humanity. war and procedures to be followed in the inception, conduct, and conclusion of war. 1758 Emerich de Vattel Lays Foundation for Formulating Crime of Aggression In his seminal treatise The Law of Nations, Swiss jurist Emerich de Vattel alludes to the great guilt of a sovereign who under- 1815 Declaration Relative to the Universal takes an “unjust war” because he is “chargeable with all the Abolition of the Slave Trade evils, all the horrors of the war: all the effusion of blood, the The first international instrument to condemn slavery, the desolation of families, the rapine, the acts of violence, the rav- Declaration Relative to the Universal Abolition of the Slave ages, the conflagrations, are his works and his crimes . -

1. Outline the Scope of the 'Nuremberg Principles'. What Is

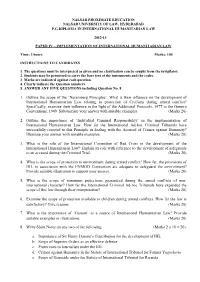

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2012-13 PAPER IV – IMPLEMENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW Time: 3 hours Marks: 100 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions must be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator. 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. Marks are indicated against each question. 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers. 5. ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS including Question No. 8 1. Outline the scope of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’. What is their influence on the development of International Humanitarian Law relating to protection of Civilians during armed conflict? Specifically, examine their influence in the light of the Additional Protocols, 1977 to the Geneva Conventions, 1949. Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 2. Outline the importance of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ in the implementation of International Humanitarian Law. How far the International Ad-hoc Criminal Tribunals have successfully resorted to this Principle in dealing with the Accused of Crimes against Humanity? Illustrate your answer with suitable examples. (Marks 20) 3. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. (Marks 20) 4. What is the scope of protection to environment during armed conflict? How far, the provisions of IHL in association with the ENMOD Convention are adequate to safeguard the environment? Provide suitable illustration to support your answer. -

1. Examine the Impact of the 'Nuremberg Principles' on The

NALSAR PROXIMATE EDUCATION NALSAR UNIVERSITY OF LAW, HYDERABAD P.G.DIPLOMA IN INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW 2009-10 PAPER IV – Implementation of International Humanitarian Law Time: 2 hours and 30 minutes Marks: 75 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES 1. The questions to be interpreted as given and no clarification can be sought from the invigilator 2. Students may be permitted to carry the bare text of the instruments and the codes. 3. All questions carry equal marks (15 marks each) 4. Clearly indicate the Question numbers ANSWER ANY FIVE QUESTIONS 1. Examine the impact of the ‘Nuremberg Principles’ on the development of IHL in the post Geneva Conventions phase. How far, the Nuremberg Principles have facilitated the implementation of the IHL? Substantiate your answer with suitable examples. 2. Examine the scope of ‘Individual Criminal Responsibility’ as an important principle of International humanitarian law. How far this principle has been invoked at the International Plane for the effective implementation of IHL? Support your answer with suitable examples. 3. Write Short Notes on any three of the following a. Importance of Marten’s Clause b. Principle of Complimentarity c. Protections to witnesses during criminal trial d. Scope of War Crimes in the Statute of International Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia e. Scope of Crimes against in the Statute of International Tribunal for Rwanda 4. Examine the scope of ‘Rape’ as interpreted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda committed during the course of Non International Armed Conflict. Refer to leading case laws. 5. What is the role of the International Committee of Red Cross in the development of the International Humanitarian Law? Explain its role with reference to the development of safeguards to an accused during the Criminal Trial. -

The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 12 Issue 3 The International Criminal Court At Ten (Symposium) 2013 The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R. Harris, Former Nuremberg Prosecutor Hans-Peter Kaul International Criminal Court (ICC) Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Hans-Peter Kaul, The Nuremberg Legacy and the International Criminal Court—Lecture in Honor of Whitney R. Harris, Former Nuremberg Prosecutor, 12 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 637 (2013), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol12/iss3/18 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NUREMBERG LEGACY AND THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT— LECTURE IN HONOR OF WHITNEY R. HARRIS, FORMER NUREMBERG PROSECUTOR HANS-PETER KAUL∗∗∗ We are assembled today in honor of Whitney R. Harris, a great American, a great advocate of the rule of law and international justice. We are also assembled here today, and tomorrow, to reflect on the International Criminal Court (ICC) and its fight against impunity until the present day. It is quite a noteworthy coincidence that this year we celebrate both the 100th birthday of Whitney R. -

From Nuremberg to Now: Benjamin Ferencz's

“Are you going to help me save the world?” From Nuremberg to Now: Benjamin Ferencz’s Lifelong Stand for “Law. Not War.” Creed King and Kate Powell Senior Division Group Exhibit Student-composed Words: 493 Process Paper: 500 words Process Paper Who took a stand for the Jews after World War II? Pondering this compelling question, we stumbled upon the story of Benjamin Ferencz. As a young lawyer, Ferencz convinced fellow attorneys at the Nuremberg Trials to prosecute the Einsatzgruppen, Hitler’s roving extermination squads, in the “biggest murder trial of the century” (Tusa). Ferencz convicted all twenty-two defendants, then parlayed his Nuremberg experience into a lifelong stand for world peace through the application of law. Our discovery that Ferencz, at age ninety-seven, is the last living Nuremberg prosecutor – and living in our home state – led to a remarkable interview. We began by researching primary sources such as oral histories and evidence gathered after the war by the War Crimes Branch of the US Army and compared these to personal accounts archived by the Florida State University Institute on World War II. Reading memos and logbooks kept by the Nazis helped us understand the significance of Ferencz’s stand at Nuremberg. Ferencz’s papers provided interviews, photographs, and documents to corroborate historical data and underscore his lifelong advocacy for peace. For a firsthand perspective, we conducted several personal interviews. Talking with Ferencz about his transformation from prosecutor to modern activist for world peace and Zelda Fuksman on surviving the Holocaust and her perspective on the Nuremberg Trials were two crucial pieces of research. -

Milch Casefertig.Rtf

TRIALS OF WAR CRIMINALS BEFORE THE NUERNBERG MILITARY TRIBUNALS UNDER CONTROL COUNCIL LAW No. 10 VOLUME II NUERNBERG OCTOBER 1946-APRIL 1949 ________ For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $2.75 (Buckram "The Milch Case " CASE NO. 2 MILITARY TRIBUNAL NO. II THE UNITED STATES OP AMERICA —against — ERHARD MILCH VII.JUDGMENT........................................................................................................................ 5 A. Opinion and Judgment of the United States Military Tribunal II* ................................... 5 COUNT TWO.................................................................................................................... 5 COUNT ONE..................................................................................................................... 9 COUNT THREE .............................................................................................................. 18 SENTENCE ............................................................................................................................. 22 B. Concurring Opinion by Judge Michael A. Musmanno.................................................... 23 COUNT ONE................................................................................................................... 23 COUNT TWO.................................................................................................................. 23 COUNT THREE ............................................................................................................. -

SCSL Press Clippings

SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE PRESS AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE PRESS CLIPPINGS Enclosed are clippings of local and international press on the Special Court and related issues obtained by the Press and Public Affairs Office as at: Wednesday, 18 April 2007 Press clips are produced Monday through Friday. Any omission, comment or suggestion, please contact Martin Royston-Wright Ext 7217 2 Local News The Transfer of Charles Taylor to The Hague: A Cause To Rethink / The News Page 3 Salone To Look Into US Human Rights Reports / Awoko Page 4 International News UNMIL Public Information Office Media Summary / UNMIL Pages 5-6 Ex-Liberian President's Associate Cries Foul / Afrol News Page 7 Visit Taylor at The Hague / Fortaylor.net Page 8 A Tribute Paid to Reason / The Walrus Magazine Pages 9-17 3 The News Wednesday, 18 April 2007 4 Awoko Wednesday, 18 April 2007 5 United Nations Nations Unies United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) UNMIL Public Information Office Media Summary 17 April 2007 [The media summaries and press clips do not necessarily represent the views of UNMIL.] International Clips on Liberia Liberia plans security force to replace UN peacekeepers MONROVIA, April 16, 2007 (AFP) - The government of Liberia plans to set up a rapid reaction force to quell any riots when UN peacekeeping troops pull out, the information minister said Monday. "This unit will assume duty upon the departure of the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL)," Lawrence Bropleh said in a statement. International Clips on West Africa AP 04/16/2007 17:42:16 Ivory Coast president, rebel chief start dismantling buffer zone PARFAIT KOUASSI ABIDJAN, Ivory Coast - With a ceremonial bulldozing of a wooden barricade, Ivory Coast's president and the man who tried to unseat him in a violent rebellion started Monday to dismantle the U.N.-patrolled buffer zone that has split the country since an attempted 2002 coup sparked civil war.